1

Neuroendocrine tumour, NET G1 (carcinoid)

2

Neuroendocrine tumour, NET G2

3

Neuroendocrine carcinoma, NEC (small- or large-cell type)

4

Mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinoma, MANEC

5

Hyperplastic and preneoplastic lesions

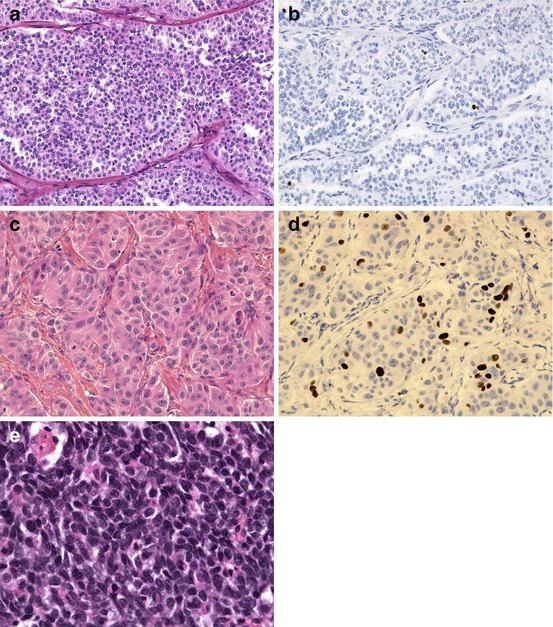

Fig. 6.1

A well-differentiated (a) neuroendocrine tumour (NET) of grade G1 (Ki-67 < 1 %, b); a well-differentiated (c) neuroendocrine tumour (NET) of grade G2 (Ki-67 = 12 %, d); a gastric small-cell poorly differentiated (e) neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC)

6.2.1.2 Basis of the Grading

The histological grading into G1, G2 and G3 is performed on the basis of the assessment of the proliferation fraction according to the ENETS scheme firstly published in 2006 [41], with the same cut-off values (Table 6.2). However, subtle differences appeared in the way to count. Indeed, in the WHO 2010 classification, it is required to count mitosis in 50 HPF (high-power field) (1 HFP = 0.2 mm2), instead of 40 HPF in the ENETS proposals. It is recommended to count the Ki-67 index using the MIB antibody as a percentage of 500–2,000 cells (whereas it was recommended to count 2,000 cells in the ENETS proposals). Grade 1 tumours have a mitotic count <2 per 2 mm2 (10 HPF) and/or ≤2 % Ki-67. Grade 2 tumours have a mitotic count between 2 and 20 per 2 mm2 and/or 3–20 % Ki-67 >20 %. Grade 3 tumours have a mitotic count >20 per 2 mm2 and/or Ki-67. If grade differs for mitosis and Ki-67 evaluation, it is suggested to consider the higher grade. It is of importance to note that in order to perform a proper evaluation of the mitotic count, the pathological specimen must have a minimal size: indeed, 50 HPF represents 10 mm2. This is not feasible in a biopsy specimen where evaluation of Ki-67 is consequently required. The prognostic value of this grading was demonstrated for foregut, midgut and hindgut NET [10, 13, 17, 18, 27, 35, 36, 45, 52]. Since the use of the WHO 2010 classification, several publications have pointed differences in the evaluation of tumour proliferation by Ki-67 or mitosis. There is a lack of concordance between grades assigned by both methods, the mitotic count being often lower than the Ki-67 count [19]. The best method to evaluate Ki-67, for example, is the use of manual or digital counting, and the best cut-off to discriminate between G1 and G2 still remains controversial [1, 11, 33, 49]. It has been recently suggested that Ki-67 is a better prognosis marker and predictor of metastases than mitoses [30].

Table 6.2

Grading for digestive neuroendocrine tumours, according to the WHO 2010 classification

Grade | Mitotic count (/2 mm2)a | Ki-67 index (%)b |

|---|---|---|

G1 | <2 | ≤2 |

G2 | 2–20 | 3–20 |

G3 | >20 | >20 |

6.2.1.3 Definition of the Five Categories of the WHO Classification

1.

Neuroendocrine tumours grade 1: these tumours are well differentiated and possess a low proliferation rate, of grade G1 (see above). The term “carcinoid tumour” can be used in place of NET G1. This term was removed from the WHO 2000 classification, and it is important to recall that it is also used to designate neuroendocrine tumours of ileal origin, secreting serotonin, and often responsible for a carcinoid syndrome. “Carcinoid tumours” have a benign connotation, but it is well known that NET G1 can be malignant and metastatic, as it is observed in the lung (Fig. 6.2).

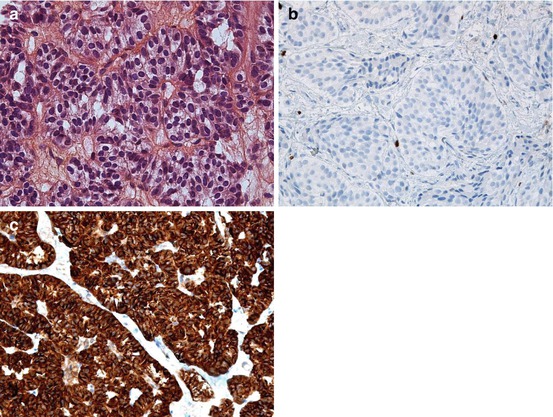

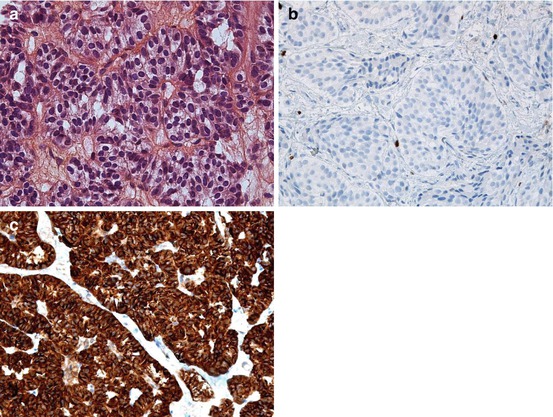

Fig. 6.2

Liver metastasis of a well-differentiated (a) pancreatic neuroendocrine tumour (NET) of grade G1 with a very low Ki-67 index <1 % (b) and a strong chromogranin A expression (c)

2.

Neuroendocrine tumours grade 2: these tumours are well differentiated and possess an intermediate proliferation rate, of grade G2 (see above). The term “atypical carcinoid” is not recommended in the WHO 2010 classification; it cannot be used for NET G2.

3.

Neuroendocrine carcinomas of large or small cells: these tumours are poorly differentiated and malignant, composed of small or large cells expressing the neuroendocrine markers chromogranin A and synaptophysin (staining might be faint or focal). They are of grade G3. The large-cell category was not included in the previous WHO 2000 classification. The small-cell category looks like the pulmonary “small-cell carcinoma” subgroup. All practitioners must be aware of the NEC category. Indeed, in the previous WHO classification, the term “carcinoma” was also used for well-differentiated tumours presenting metastases and/or invading the muscular layer in the digestive tract. It is important to document the tumour differentiation in the pathology reports in order to make impossible such error. Another important issue is the relationship between the grade G3 and the differentiation in this category. Indeed, the WHO classification suggests that all G3 tumours are poorly differentiated carcinomas. However, it is now known that the G3 group is heterogeneous, containing both well-differentiated NET and poorly differentiated NEC, the former being less aggressive with a lower Ki-67 index and a lower response rate to cisplatin-based chemotherapy [51]. It is not possible to classify “well-differentiated G3” tumours according to the WHO classification.

4.

MANECs (mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinomas) have both a neuroendocrine and an exocrine glandular phenotype. Thirty per cent of each component must be at least identified for this definition. The new term “MANEC” replaces the previous “mixed endocrine-exocrine tumour”. Theoretically, the neuroendocrine component may be well or poorly differentiated. The exocrine component may be composed of acinar carcinoma cells. The frequency of MANEC and the type of exocrine or neuroendocrine component depend on the location in the digestive system. For example, in the colon, MANECs are more frequent and they often contain a poorly differentiated neuroendocrine component [28].

5.

Hyperplastic and preneoplastic lesions.

6.2.2 The 2009 AJCC-UICC TNM

6.2.2.1 Introduction

In 2009, the 7th edition of the American Joint Cancer Committee-Union Internationale Contre le Cancer (AJCC-UICC) TNM classification was published [47], including for the first time digestive neuroendocrine tumours. It followed the first TNM classification which was proposed in 2006 (for NET of the stomach, duodenum and pancreas) and in 2007 (for NET of the ileum, colon/rectum and appendix) by a working group of the European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (ENETS) [41, 42]. In the AJCC-UICC classification, high-grade (poorly differentiated) NECs are classified separately, by using the exocrine classification established in respective sites. When considering well-differentiated NETs, the AJCC-UICC TNM is similar to the previous ENETS/TNM proposals for intestinal anatomical sites but differs for other locations (the pancreas, stomach and appendix). It is important to document the pathological features, such as invasion and tumour size, to allow the translation of the staging between the classifications [23].

6.2.2.2 TNM Staging in the Different Digestive Locations

See Table 6.3 for details and comparison between UICC and ENETS T categories.

Table 6.3

T categories in the UICC and ENETS classifications of digestive neuroendocrine tumours, in the pancreas, stomach, small intestine, appendix and colon/rectum

Pancreas-ENETS | Pancreas-UICCa | |

|---|---|---|

T1 | Tumour confined to pancreas, ≤2 cm | Idem |

T2 | Tumour confined to pancreas, 2–4 cm | Tumour confined to pancreas, >2 cm |

T3 | Tumour confined to pancreas and >4 cm or invading duodenum or bile duct | Tumour extends beyond pancreas, without involvement of coeliac axis or superior mesenteric artery |

T4 | Tumour involves coeliac axis or superior mesenteric artery or adjacent organs (stomach, spleen, colon, adrenal) | Tumour involves coeliac axis or superior mesenteric artery |

Stomach-ENETS | Stomach-UICC | |

|---|---|---|

Tis | In situ/dysplasia (<0.5 mm) | Idem |

T1 | Tumour invading mucosa or submucosa, ≤1 cm | Idem |

T2 | Tumour invading muscularis propria or subserosa or >1 cm | Tumour invading muscularis propria or >1 cm |

T3 | Tumour penetrating serosa | Tumour invading subserosa |

T4 | Tumour invading adjacent structures | Tumour penetrating serosa or invading adjacent structures |

Small intestine-ENETS | Small intestine-UICC | |

|---|---|---|

T1 | Tumour invading mucosa or submucosa, ≤1 cm | Idem |

T2 | Tumour invading muscularis propria or >1 cm | Idem |

T3 | Jejunum, ileum: tumour invading subserosa Ampulla, duodenum: tumour invading pancreas or retroperitoneum | Idem |

T4 | Tumour invading serosa or other organs | Idem |

Appendix-ENETS | Appendix-TNMb | |

|---|---|---|

T1 | Tumour ≤1 cm; invading submucosa, muscularis propria | T1a: ≤1 cm T1b: >1–2 cm |

T2 | Tumour ≤2 cm; invading submucosa, muscularis propria, minimally (≤3 mm) subserosa/mesoappendix | Tumour >2–4 cm or invading the cecum |

T3 | Tumour > 2 cm or largely (>3 mm) invading subserosa/mesoappendix | Tumour >4 cm or invading the ileum |

T4 | Tumour invading serosa or other organs | Idem |

Colon/rectum-ENETS | Colon/rectum-UICC | |

|---|---|---|

T1 | Tumour invading mucosa or submucosa, T1a < 1 cm, T1b: ≥1–2 cm | Idem |

T2 | Tumour invading muscularis propria or >2 cm | Idem |

T3 | Tumour invading subserosa or mesorectum | Idem |

T4 | Tumour penetrating serosa or invading adjacent structures | Idem |

Pancreas

In this location, the AJCC-UICC applies the same TNM as the one used for classifying adenocarcinomas, either for well-differentiated or poorly differentiated tumours. In the AJCC-UICC TNM, invasion of the peripancreatic fat applies to pT3 tumours as compared to tumour size >4 cm in the ENETS TNM (Table 6.3). The size cut-off of 4 cm, which is reported to be an important prognostic factor [45], is not included in the AJCC-UICC classification. There is a discrepancy between the ENETS and UICC staging in the pancreas in a large proportion of cases [29].

Stomach

In this location, a Tis stage is defined (in situ tumour, less than 0.5 mm). The UICC and ENETS classifications differ. Tumours invading the subserosa are T2 according to ENETS and T3 according to UICC.

Intestine

The UICC and ENETS classifications are identical in the small intestine. The T2 and T3 stages apply to tumours invading the muscularis propria and the subserosa, respectively, whereas T4 tumours penetrate the serosa (Table 6.3). In the rectum, the stage and grade according to ENETS/WHO are correlated with survival (Weinstock).

Appendix

According to the UICC classification, the tumour size is a very important criterion to classify NET in this location. According to ENETS, the invasion into the mesoappendix should be evaluated to distinguish T2 and T3 tumours (T3 tumour >2 cm and/or >3 mm extension into the mesoappendix).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree