CHAPTER 310 Evaluation and Management of Spinal Axis Tumors

Benign and Primary Malignant

Although up to 90,000 new cases of metastatic spinal disease are diagnosed each year, primary tumors of the vertebral column are exceedingly rare. Less than 10% of all primary bony tumors arise from the vertebral column, and it is estimated that only approximately 7500 new primary spinal tumors are diagnosed each year in the United States.1 Primary vertebral column tumors can be benign or malignant. Commonly occurring benign and malignant spinal tumors are listed in Table 310-1. In this chapter, the clinical features and surgical management of common primary spinal tumors are discussed.

TABLE 310-1 List of Common Benign and Malignant Primary Vertebral Column Tumors

| Benign Primary Spinal Tumors |

| Malignant Primary Spinal Tumors |

Clinical Features

In general, primary spinal tumors are typically diagnosed at a younger age than metastatic spinal tumors. Several of the primary spinal tumors are related to commonly occurring childhood primary bone tumors seen in other skeletal regions, including Ewing’s sarcoma, osteoblastoma, and giant cell tumors (GCTs). Nevertheless, primary vertebral tumors also occur in adults. The most common benign vertebral column tumor in adults is vertebral hemangioma. Based on autopsy studies, approximately 10% to 20% of the population have vertebral hemangiomas.2,3 In contrast, the most frequently occurring malignant primary vertebral tumor in adults is plasmacytoma or multiple myeloma. Although they are lymphoproliferative tumors, they most commonly arise from bone marrow within the vertebral bodies. Moreover, patients with plasmacytoma or multiple myeloma most often have mechanical back pain, spinal fractures, or symptoms of epidural spinal cord compression.

The most frequent initial symptom in patients with primary spinal tumors is pain. Weinstein found that almost 85% of patients with primary spinal tumors complain of pain.4 Pain related to neoplastic disease may be difficult to differentiate from that caused by other benign conditions; however, it is often worse at night and occurs even at rest. The pain can also be axial or mechanical in nature secondary to erosion of the vertebral column by tumor or spinal instability. Radicular pain can occur if the spinal roots are irritated. Progressive neurological deficits can be associated with either benign or malignant primary spinal neoplasms. However, an aggressive lesion is more likely to be accompanied by pathologic fractures or significant spinal cord compression. Spinal deformity can occur in patients with primary spinal tumors, but it is rare for patients with primary spinal tumors to have gross spinal instability. Nevertheless, one classic finding in patients with osteoid osteoma is painful scoliosis.5–9

Clinical Evaluation

Young patients with protracted spinal pain, pain that is worse at night, pain that occurs at rest, or pain associated with neurological deficits should prompt a medical evaluation for spinal tumors. The initial study to evaluate for spinal tumors is generally plain radiography. Plain radiographs can localize the lesion and are diagnostic in selected cases. However, plain radiographs require approximately 50% loss of mineralization before osteolytic lesions are detected.10 As a result, plain radiographs have low sensitivity for detecting primary spinal tumors, and they often fail to detect small or early tumors.

Several primary spinal tumors have characteristic imaging findings on plain radiography, CT, and MRI. Occasionally, congruent findings with these modalities can be diagnostic and obviate the need for further testing or procedures, the primary example of which is an aneurysmal bone cyst (ABC). ABCs typically have cystic structures with fluid-fluid levels from blood degradation products on MRI and CT (Fig. 310-1). In selected cases, identification of the characteristic CT and MRI findings can eliminate the need for tissue biopsy and avoid the potential complication of a hematoma.

Other imaging techniques that are valuable in the evaluation of primary spinal tumors include bone scans, positron emission tomography (PET), and angiography. A bone scan is a nuclear medicine study that can identify new areas of bone growth or breakdown resulting from tumor involvement. The lesion can be considered “cold” or “hot,” depending on the amount of local cell activity and function in the osteocytes. Bone scans generally have high sensitivity but poor specificity. Small lesions that are not well visualized with plain radiography, CT, or MRI, such as osteoid osteomas, can be detected with a bone scan.11,12 PET is another nuclear medicine imaging technique that involves the use of a metabolically active radiotracer. The most commonly used tracer is fludeoxyglucose F 18. After intravenous injection, it accumulates and becomes concentrated in the neoplasm. PET is emerging as one of the most commonly used diagnostic tools in oncology.13–19 It has high sensitivity and provides both anatomic and functional information regarding a tumor.

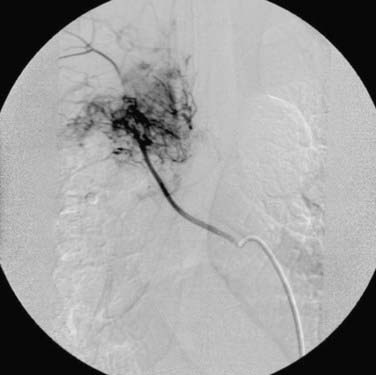

Angiography is used for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes in the management of primary spinal tumors. It can assist in the diagnosis of a vascular lesion, such as an ABC or vertebral hemangioma. In addition, angiography can be used to determine the anatomy and extent of the vascular supply to a primary spinal tumor before surgical intervention (Fig. 310-2). Lesions, including ABCs, hemangiomas, GCTs, and sarcomas, are often associated with increased vascularity. Preoperative embolization in these cases can reduce the intraoperative blood loss associated with surgery and decrease the perioperative morbidity associated with blood loss and transfusion of blood products.20–26

Histopathologic Diagnosis

To make an accurate diagnosis, a CT-guided biopsy is typically performed to obtain tissue specimens for histopathologic analysis. CT-guided biopsy is a fast, economical, and minimally invasive procedure. In addition, it is a safe procedure with a low complication rate. In several studies, percutaneous CT-guided biopsy of spinal lesions has been demonstrated to have a diagnostic accuracy of up to 93%.27–31 Rimondi and colleagues, in their review of 430 patients who underwent percutaneous CT-guided biopsy, found that the success rate for accurate diagnosis is higher with malignant lesions.31 Conversely, the success rate was lower with inflammatory lesions, particularly chronic ones.31 An accurate diagnosis can have a significant impact on treatment and the overall prognosis. In the following section, specific evaluation and management of common benign and malignant primary spinal tumors are discussed.

Benign Primary Spinal Tumors

Aneurysmal Bone Cyst

ABCs were first described by Jaffe and Lichtenstein in 1942.32 ABCs are cystic and osteolytic lesions that typically affect patients younger than 20 years, and they have a slight female preponderance. ABCs usually arise from long bones, but about 12% to 30% of cases involve the spine.33–36 These tumors typically involve the posterior elements, and the thoracic spine is the most frequent site of involvement.36

CT and MRI are most useful for the assessment of ABCs. Expansile, osteolytic, and cystic lesions with thin cortical eggshells are seen on CT. In addition, a fluid-fluid level demonstrating the layering of blood products from previous hemorrhages is seen within the cystic lesions. ABCs have a heterogeneous appearance on both T1- and T2-weighted MRI. Again, a fluid-fluid level is usually seen within the cystic lesions, with heterogeneous signals denoting the various hemoglobin degradation products (see Fig. 310-1). Histologically, ABCs show cystic cavities filled with blood products separated by fibrous septa. They are expansile and associated with significant bony destruction with thin layers of reactive cortical bone surrounding the lesion.

Although the majority of ABCs are primary lesions, it is known that they can be secondary lesions associated with other spinal tumors, including GCT, osteoblastoma, chondroblastoma, and osteogenic sarcoma.35 Generally, symptomatic patients are treated by embolization or surgery. Embolization can be used as first-line and the sole therapy for ABCs.36–45 Several successful cures after embolizations of ABCs have been reported.46–48 In addition, embolization is used preoperatively to decrease intraoperative blood loss and morbidity.33,37,38,42,44 Surgically, complete excision of the tumor is the goal but may be difficult. Incomplete tumor excision may be associated with significant rates of tumor recurrence.33,49–52 Radiotherapy can be considered in patients with residual or recurrent tumor. ABCs are sensitive to radiation, but the recurrence rate remains significant despite adjuvant radiotherapy.33,52–55 In addition, radiation therapy in young patients with these benign tumors is concerning for the development of radiation-induced sarcomas in the future.

Hemangiomas

Vertebral hemangiomas are the most commonly occurring benign primary spinal tumors. They affect 10% to 12% of the population and are often incidental findings detected during imaging of the thoracolumbar spine. Vertebral hemangiomas are considered non-neoplastic, and only about 1% of those affected are symptomatic.2,3,56,57 Aggressive hemangiomas can cause local pain from involvement of the vertebral body. In addition, they can cause radiculopathy from nerve root compression or myelopathy with epidural disease and spinal cord compression (Fig. 310-3). Moreover, pathologic fractures can also occur with vertebral hemangiomas.

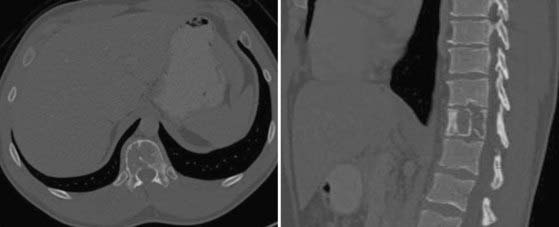

On CT, vertebral hemangiomas display patterns of coarse vertical striations or bony trabeculation that are often referred to as “honeycomb” or “polka dot” signs, respectively (Fig. 310-4).56 MRI of these lesions demonstrates hyperintense signals on both T1- and T2-weighted sequences. The combination of these characteristic CT and MRI findings is typically sufficient to diagnose vertebral hemangiomas, particularly those that are incidental findings during medical evaluation for other complaints. However, in the event of uncertainty, percutaneous CT-guided biopsy can be performed to obtain a tissue diagnosis. On histopathologic examination, hemangiomas are composed of an aggregate of irregularly shaped sinusoidal channels of thin-walled vessels with erosion of the bony architecture.

FIGURE 310-4 Sagittal and axial computed tomographic scans of a hemangioma illustrating the “honeycomb” and “polka dot” signs.

Although the prevalence of vertebral hemangiomas is high, they seldom cause clinical symptoms. These lesions most commonly involve the thoracic and lumbar spine.2,57 The lower thoracic spine is the most frequent site of symptomatic vertebral hemangiomas,2,58,59 and they become symptomatic by expansile enlargement of the vertebral body, pedicle, or lamina. Direct invasion of the extradural space can also occur and cause epidural spinal cord compression. In addition, there appears to be an association between pregnancy and the development of symptomatic vertebral hemangiomas.60,61

The majority of vertebral hemangiomas are managed by medical observation. Painful hemangiomas can be treated by vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty. Galibert and associates described the first attempt to treat these lesions by percutaneous injection of acrylic cement.62 Since their report, vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty is now well accepted as primary treatment of painful vertebral hemangiomas without neurological compromise.60,63–69 In symptomatic patients with spinal cord compression or neurological symptoms, surgical excision of the tumor plus spinal cord decompression is the treatment of choice. Preoperative angiography to determine the vascularity of the tumor, followed by tumor embolization, is recommended to decrease intraoperative blood loss (see Fig. 310-2).2,57,60 Postoperative radiotherapy for these lesions is controversial but should be considered in patients with significant residual or recurrent tumors.2,70

Osteoid Osteoma and Osteoblastoma

Osteoid osteomas are benign bone lesions that arise from cancellous bone throughout the musculoskeletal system. Less than 10% of these lesions originate from the spine. By definition, osteomas are smaller than 2 cm. Those larger than 2 cm are considered osteoblastoma. Patients with osteomas are mostly seen in their teenage years initially, and there is a slight male preponderance. Most patients have pain that is typically worse at night and relieved with salicylates. Occasionally, these patients will have painful scoliosis, which is a classic manifestation of this tumor.5–956

Osteoid osteomas most commonly affect the posterior elements of the spine, with the lumbar spine being the most frequently involved site.56,57 A round or oval lesion with a radiolucent center and peripheral sclerosis is the radiographic hallmark of osteomas. Radiographs can help diagnose these lesions but have low sensitivity. CT is the imaging modality of choice and can determine the extent of vertebral involvement. Radionuclide bone scans can also be used to detect osteomas and often demonstrate significant uptake by the tumor. Bone scans have high sensitivity and are particularly useful for detecting small lesions that are otherwise not detected on radiographs or CT.71–73 On histologic analysis, osteomas are composed of well-organized and interconnected trabeculation in a background of vascularized connective tissue with surrounding reactive cortical bone.56

Conservative management with salicylates should be the initial treatment of patients with osteoid osteoma.72–74 Patients who fail conservative management may undergo surgical excision. Curettage or intralesional excision is acceptable, but the goal of surgery is complete removal to prevent recurrence. There is evidence that alcohol, laser, or radiofrequency ablation is an effective alternative treatment of these tumors.75–83

Osteoblastomas are radiographically and histologically similar to osteoid osteomas. However, osteoblastomas are larger (>2 cm) and are associated with more constant pain that is not relieved by salicylates.56,57 Approximately 90% of patients with osteoblastoma are initially seen in their second or third decade of life. Osteoblastomas are associated with a higher rate of neurological compromise because of their larger size and more aggressive biology. Unlike osteomas, complete surgical excision is the primary treatment. However, this can be challenging because of the tumor’s larger size and more diffuse involvement. Wide en bloc excision is preferable to decrease the risk for tumor recurrence. A recurrence rate of up to 50% is associated with intralesional or marginal resection of aggressive osteoblastomas.84–87 Irradiation of these tumors is controversial, but it can be considered for residual or recurrent tumors.88–90

Enchondroma

Enchondroma is a common benign cartilaginous tumor that accounts for 5% of all bone tumors, and it affects the short tubular bones of the hands and feet in more than 50% of cases. It is the most common primary tumor in the hand and is normally found in the diaphysis. On the contrary, it is extremely rare in the vertebral column and accounts for only about 2% of all cases.91–97 Enchondroma can arise either from hyperplasia of immature spinal cartilage trapped within the vertebral bodies or from metaplasia of connective tissues in connection with the spine. Most patients with enchondroma come to medical attention during the second to fourth decades, and there is no gender predilection.

Radiographically, enchondromas show well-circumscribed, round to oval osteolytic lesions that may widen the cortex. On CT, they are homogeneous lesions with or without calcification that may enhance with injection of contrast material. On MRI, enchondromas have intermediate to low signal intensity on T1-weighted sequences and high signal intensity on T2-weighted images (Fig. 310-5).94

Solitary and painless enchondromas can be observed medically. Painful lesions or those associated with neurological symptoms should be treated. In addition, enchondromas with large size, a large unmineralized component, and elevated activity on bone scans are concerning for malignancy.94 Lesions with these features should undergo biopsy, followed by surgical excision. Complete tumor excision is the goal and can be achieved by intralesional resection. Recurrence after surgical excision is rare, and malignancy should be excluded in such cases. Malignant degeneration is possible and is seen in up to 30% of those with conditions involving multiple enchondromatosis, such as Ollier’s disease or Maffucci’s syndrome.98–100

Osteochondroma

Spinal osteochondromas are uncommon primary spinal tumors that account for less than 4% of all primary spine tumors. These benign spinal tumors arise during development when cartilage is trapped outside the physeal plate.56 Radiation is also an unusual cause of this tumor.101–105 Patients with radiation-induced osteochondroma often received radiotherapy at an age younger than 2 years, and there is typically a latent period of 17 months to 9 years.103,104

Patients with osteochondroma are typically seen initially in their third or fourth decades, and there is a male preponderance. Most patients have a solitary lesion, except in cases associated with hereditary multiple exostoses. Osteochondromas have a predilection for the cervical spine, with the axis being the most common site of involvement.56 Patients may complain of pain or myelopathy. Osteochondroma most commonly affects the posterior elements, and patients can have a palpable mass. Radiographically, these lesions are often pedunculated in appearance and are composed of healthy bone with a cartilaginous cap.56 CT is the test of choice to detect the exostosis and the pathognomonic finding of the exostotic lesion in continuity with the cortex and bone marrow of the underlying bone.56,57 MRI can help in evaluating the relationship of the lesion to its surrounding soft tissues and examining the cartilaginous end cap. Thickening of the cartilaginous cap greater than 1 to 2 cm is suggestive of malignant transformation to chondrosarcoma.56

Medical observation is indicated for incidental or dormant lesions that are stable in size, whereas surgical excision is the treatment of choice for symptomatic lesions. Complete excision is the goal, and intralesional resection to achieve complete excision is acceptable, but incomplete excision may result in tumor recurrence.56 In addition, malignant transformation of osteochondroma to chondrosarcoma has been reported.106–109 En bloc excision should be considered for aggressive lesions.110,111 However, en bloc tumor resection is technically demanding in patients with tumor involvement of the axis or subaxial cervical spine. Radiation therapy is ineffective and not generally considered for the treatment of these tumors. Furthermore, radiation-induced transformation of these benign tumors to chondrosarcoma is a concern.107,112

Chondroblastoma

Chondroblastoma is a rare primary bone tumor that accounts for about 1% of all cases.56 Chondroblastoma arises from immature cartilage and is most often seen in the epiphyseal region of long bones. Although only a few cases of spinal involvement have been reported in the literature, patients with chondroblastoma are typically seen in adolescence or young adulthood. There is a slight male preponderance. Most patients complain of pain, but spinal canal invasion is common with chondroblastoma.57 Because its radiographic findings are nonspecific, CT-guided biopsy should be performed for definitive histopathologic diagnosis. On histologic analysis, chondroblastomas consist of round or polygonal chondroblast-like cells and multinucleated giant cells in a background of cartilaginous intercellular matrix and focal calcification.113–115 The limited surgical experience with chondrosarcoma demonstrates significant recurrence rates ranging from 24% to 100% with incomplete resection. Consequently, wide en bloc resection should be highly considered in the management of this rare primary spinal tumor.113–115

Giant Cell Tumor

GCTs account for about 7% to 10% of all cases of primary spinal tumor.56,57 Patients with GCTs are most often seen initially in the third or fourth decades, and the sacrum is the most common site. There is a slight female preponderance associated with GCTs. Common symptoms of GCTs include pain, weakness, sensory deficit, and bladder or bowel dysfunction. Those with sacral GCTs often have large tumors as a result of significant tumor growth before the development of neurological symptoms.

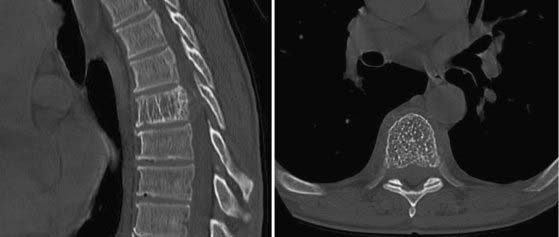

Histologically, GCT is composed of abundant osteoclastic giant cells mixed with spindle cells. Based on this appearance, it is speculated that GCT originates from osteoclasts. Radiographically, GCT demonstrates an expansile mass with destruction of the vertebral bodies. These tumors generally involve the vertebral body but can extend to involve the posterior elements (Fig. 310-6). In the sacrum, GCT can involve the vertebral body bilaterally and can extend across the sacroiliac joints.56

GCTs are locally aggressive and associated with a high recurrence rate after incomplete excision. As a result, the prognosis for patients with GCTs is not as favorable as for those with other benign primary spinal tumors. Before surgery, it is advisable to perform tumor embolization because these tumors are vascular and associated with significant intraoperative blood loss. Complete surgical tumor excision is the treatment of choice for patients with GCTs. However, complete excision is not always possible, given the large size of these lesions and their tendency to invade local surrounding tissues. Wide en bloc excision of these tumors is the preferred surgical treatment and is associated with a lower recurrence rate.116–121 Wide en bloc resection should be attempted when feasible; however, it may require judicious sacrifice of normal surrounding tissues, including nerve roots. Intralesional resection is an alternative treatment when en bloc excision is not possible, but it is associated with significant rates of local recurrence.119

Radiation therapy can be used as adjuvant treatment after incomplete resection or tumor recurrence. In their review of the literature, Leggon and coauthors identified and reviewed 239 lesions treated over the past 50 years.118 Their study demonstrated that there was no statistically significant difference in the recurrence rate after radiotherapy, incomplete surgical resection, or incomplete surgical resection followed by radiotherapy. The recurrence rate in these three groups ranged from 46% to 49%. In contrast, the recurrence rate was 0% in those who underwent wide surgical excision. Therefore, radiation therapy alone appears to be a viable alternative treatment when wide surgical excision is not achievable. Nevertheless, there is concern for radiation-induced sarcoma in long-term survivors. Leggon and colleagues found that radiation-induced sarcoma developed in 11% of patients who received radiotherapy for GCT as primary treatment or after tumor recurrence.118

Malignant Primary Spinal Tumors

Chordoma

Chordoma is an uncommon tumor that accounts for 2% to 4% of all primary malignant bone tumors. The annual incidence rate is low, around 1 case per 100,000 per year.122 However, other than lymphoproliferative tumors, chordoma is the most common primary malignant tumor of the spine in adults. These tumors arise from remnants of the notochord and can be found from the skull base to the coccyx. Most chordomas arise from the clivus or the sacrococcygeal regions. In the spine, the sacrum is the most common site of disease, followed by the lumbar spine and then the cervical spine.122

Patients with chordoma are generally seen in middle age, with the peak incidence in the fifth or sixth decades of life. There is a slight male preponderance in patients with spinal chordomas.122 Initial symptoms in these patients include pain, weakness, sensory disturbance, and bladder or bowel dysfunction. Similar to GCTs, chordomas have insidious growth and are often large at the time of detection. On radiography and CT, these tumors have an osteolytic lesion near the center of the vertebral body with surrounding bony expansion and intratumor calcification. MRI of chordoma with T1-weighted sequences typically demonstrates low or intermediate intensity within the lesion. On T2-weighted imaging, chordoma displays its characteristic high intensity signals as a result of the high water content within these tumors (Fig. 310-7).56 Enhancement of the tumor is generally seen with infusion of intravenous contrast material.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree