Forensic Aspects of Brain Tumors

Juan C. Troncoso

Charles G. Eberhart

The purpose of this chapter is to review and discuss the forensic aspects of brain tumors, in particular, their role as the cause of sudden death and as source of seizures and other clinical manifestations relevant to forensic determinations of the cause and manner of death. This chapter will not review the histopathology or biology of brain tumors, for which the reader is referred to specialized textbooks.1

The diagnosis and examination of brain tumors in forensic neuropathology is important for several reasons.2 In the case of tumors diagnosed during life, examination of the tumor helps to decide whether the neoplasm contributed to or was the cause of death. Furthermore, the examination of these lesions can contribute to a better understanding of the biology of the neoplasms and, sometimes, to the response to various therapeutic modalities. For example, the possibility of examining an entire glioma allows for cytogenetic analyses that can shed light on molecular mechanisms of malignant transformation of these tumors. However, the most important contribution of the forensic neuropathologist in this area is the identification of undiagnosed lesions that cause sudden and unexpected death or contribute to fatal accidents.

Tumors of the brain and spinal cord are not uncommon in the practice of forensic neuropathology. As shown in Table 13.1, in 54, 873 autopsies conducted at the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner of the State of Maryland between 1980 and 1999, we encountered 76 primary tumors (0.14%) of the central nervous system.3 The most frequent of these tumors were meningiomas (35.5%), followed by gliomas (22.4%). Although metastatic brain tumors are almost as common as primary tumors in the general adult population, we see very few brain metastases in forensic autopsies, probably as a result of selection bias. Given our experience, despite improvements in imaging techniques, such as computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging, which contribute to early detection of central nervous system neoplasms, we will continue to encounter undiagnosed tumors of the brain in forensic autopsies.

BRAIN TUMORS AS CAUSE OF SUDDEN AND/OR UNEXPECTED DEATH

The association of brain tumors and sudden death is well established and has been reported by several authors. Huntington et al.4 reported undiagnosed brain tumors in 0.42% of 3, 543 autopsies conducted between 1950 and 1955 at the Kern County Coroner’s Office in Bakersfield, California. Di Maio and Di Maio5 reported brain tumors in 0.16% of 17, 404 autopsies conducted between 1960 and 1970 at the Brooklyn Office of the Medical Examiner in New York City. DiMaio et al.6 found a slightly higher frequency (0.17%) of unsuspected primary intracranial neoplasm in 10, 995 consecutive autopsies performed by the Dallas County Medical Examiner’s Office in Texas from 1970 to 1977. In our experience at the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner of the State of Maryland, among the 76 brain tumors in the series described above, 11 presented as cases of sudden death and accounted for 0.02% of the 54, 873 autopsies conducted in a 20-year period. This frequency may be as high as 0.05% if we include an additional 16 cases in which medical information was insufficient to determine whether the tumors were the cause of death or if an antemortem diagnosis had been made.3 Even under these circumstances, this frequency is less than that observed in previous studies of deaths in undiagnosed brain tumors. This decrease is most likely due to improved

detection methods, such as computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging, and may also reflect improved access to health care. An autopsy series of 117 consecutive supratentorial glioblastoma multiforme revealed that 20 patients (17%) expired unexpectedly without ante mortem diagnosis.7

detection methods, such as computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging, and may also reflect improved access to health care. An autopsy series of 117 consecutive supratentorial glioblastoma multiforme revealed that 20 patients (17%) expired unexpectedly without ante mortem diagnosis.7

TABLE 13.1 Primary Central Nervous System Tumors Identified in 54, 873 Autopsies3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Brain tumors can cause death by several individual or combined mechanisms. These common mechanisms include increased intracranial pressure as a result of the tumor mass and surrounding edema (Case 13.1), bleeding (Case 13.2), acute hydrocephalus owing to obstruction of cerebrospinal circulation (Cases 13.3 and 13.4), infiltration of the brainstem by the tumor (Case 13.5), or seizures (Cases 13.6 and 13.7).

Increased Intracranial Pressure

Increased intracranial pressure leads to distortions and displacement of brain parenchyma and ventricles, known as herniations (cingulate, transtentorial, or tonsillar) (see Chapter 8), which eventually interfere with structures such as the hypothalamus and medulla, which are critical to sustain vital functions. Also, brain herniations are frequently complicated by vascular lesions such as hemorrhagic infarctions and brainstem hemorrhages. A study of the cause of death in 117 cases of supratentorial glioblastoma identified a potential cause of death in 93% of patients.7 The causes of death included herniation, surgical complications, severe systemic illness, brainstem invasion by tumor, and radiation-induced cerebral injury. Herniation was present in 61% of patients, but most had an additional identifiable cause of death. Thus, the presence of herniation per se does not exclude other causes of death. However, among those with no antemortem diagnosis, herniation was the most frequent cause of death. By contrast, in patients with premortem diagnosis and therapy, herniation was uncommon.

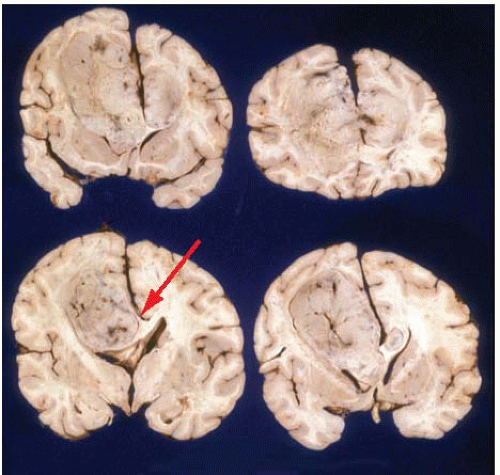

Case 13.1

A 29-year-old woman was found dead on the bathroom floor. She had recently complained of headaches and suffered episodes of vomiting. Coronal sections of the brain revealed a large left frontoparietal mass (Fig. A). This mass had a volume of approximately 250 mL, occupied most of the white matter of the left cerebral hemisphere, and extended across the corpus callosum into the right hemisphere. The mass obliterated the corpus callosum and frontal horns of the lateral ventricles. The lateral ventricles were slightly dilated, but there was no elongation of the third ventricle or displacement of adjacent hypothalamic structures. Microscopic examination revealed a glioblastoma multiforme. In this case, the best explanation for sudden death is the mass effect of the tumor. However, the possibility of a seizure cannot be completely ruled out.

Hemorrhage into a Brain Tumor

Hemorrhage into a brain tumor can be massive and cause death by mass effect or by inundation of the ventricles, resulting in acute obstructive hydrocephalus. In adults, hemorrhages usually occur in malignant gliomas or glioblastoma, as in the case illustrated in Case 13.2. Occasionally, an ependymoma can bleed massively into the ventricular system.8 In children, fatal hemorrhage into a tumor has been reported in cerebellar medulloblastoma, optic chiasm astrocytoma, pineal gland teratoma, fourth ventricle ependymoma, 9 and primitive neuroectodermal tumor.10

Obstruction of Cerebrospinal Fluid Circulation and Acute Hydrocephalus

The dynamic of cerebrospinal fluid production in the choroid plexus, its circulation throughout the ventricular system and subarachnoid space, and then its reabsorption via the arachnoid granulations into the superior sagittal sinus are critical for the homeostasis of the brain. Tumors can easily obstruct the circulation of cerebrospinal fluid and lead to the abrupt enlargement and increase in pressure of the ventricular system. This condition is also known as acute hydrocephalus, and it is potentially fatal. Examples of this type of mechanism are tumors of the third ventricle, the most common of which is the colloid cyst (which is not truly a tumor) (Case 13.3)11, 12, 13, 14, 15; ependymomas and other less common tumors, such as meningiomas, lipomas16 (Fig. 13.1), and subependymomas 17; and tumors that can grow into the fourth ventricle, such as ependymomas (Fig. 13.2), subependymomas, 18 and primitive neuroectodermal tumors or medulloblastomas.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree