Forensic psychiatry

The association between mental disorder and crime

Psychiatric aspects of specific crimes

Psychiatric aspects of being a victim of crime

The role of the psychiatrist in the criminal courts

The treatment of offenders with mental disorder

The management of violence in healthcare settings

Introduction

Chapter 4 covered general legal and ethical issues in the practice of medicine and psychiatry. This chapter is concerned with other aspects of psychiatry and the law covered by the term forensic psychiatry, which is used in two ways.

1. Narrowly, it is applied to the branch of psychiatry that deals with the assessment and treatment of mentally abnormal offenders.

2. Broadly, the term is applied to all legal aspects of psychiatry, including the civil law and laws regulating psychiatric practice.

Forensic psychiatrists are concerned with both of these issues. In addition, they also assess risk and treat people with violent behaviour who have not committed an offence in law. They have a growing role in the assessment and treatment of victims.

Offenders with mental disorders constitute a minority of all offenders, but they present many difficult problems for psychiatry and the law. These include legal issues, such as the relationship between the mental disorder and the crime, which may affect the court’s determination of responsibility, and practical clinical questions, such as whether an offender needs psychiatric treatment, and finding the appropriate setting for that treatment.

The psychiatrist therefore needs knowledge not only of the law but also of the relationship between particular kinds of crime and particular kinds of psychiatric disorder. Mental health services form only a small part of the social and legal response to criminal deviance. The psychiatrist who is working with offenders needs to be able to liaise with others in the criminal justice system, such as lawyers, prison staff, and probation officers. Concepts of deviance, guilt, and legality are influenced by legal, political, and social factors, as well as by clinical issues.

In reading this chapter it is important to be aware of the very large differences between countries and jurisdictions, with substantial national variations in epidemiology, definitions of crime, legal practice, and the role of the psychiatrist. Readers need to be aware of legal issues and procedures in their jurisdiction. In the following account, the situations and procedures in the UK (and more especially England and Wales) are used as examples to illustrate general themes. Ethical issues are summarized in Box 24.1.

General criminology

There is a very large literature on criminology and many theories of the causes of crime; interested readers are referred to criminology textbooks (see Maguire and Morgan, 2002). Most theories have emphasized the sociological aspects of crime and deviance, including social and economic causes of crime in the family, peer group, and subculture. These include poverty, poor schooling, and unemployment. The proposed predisposing social and individual factors are often interrelated, so simple conclusions are not possible. However, these causes are widely considered more important than individual factors such as genetics and psychological traits. Despite this, psychological risk factors determine most correctional and forensic mental health programmes, which encourage, for example, the development of coping skills (Dowden et al., 2003).

Prevalence

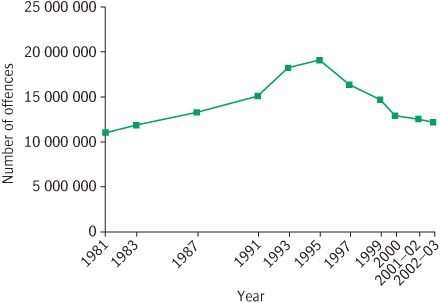

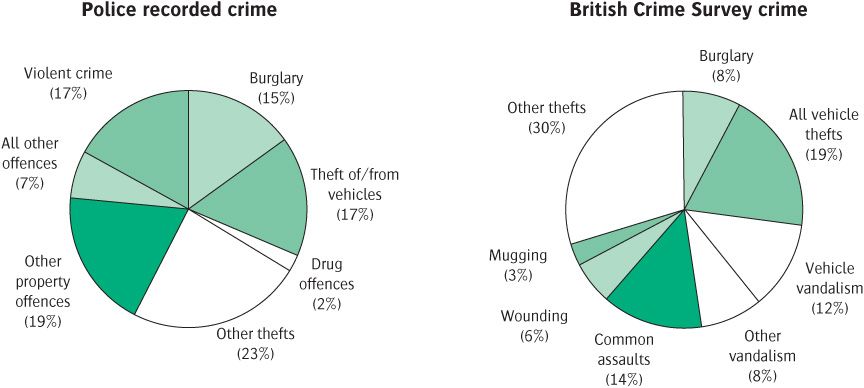

Prevalence figures must be viewed cautiously because they depend on reporting, and much criminal behaviour is unrecorded by the police. This is especially true of violence within the home, such as rape, child abuse, or partner battering. Crime surveys probably provide more accurate figures. Data from the British Crime Survey are shown in Figure 24.1, and crimes recorded by the police in England and Wales during the period 2002–2003 are shown in Figure 24.2, classified by type of offence together with the same data for the British Crime Survey (Simmons and Dodd, 2003). Property offences are the most common type of crime, but forensic mental health services are most likely to be involved with crimes of interpersonal violence.

National differences

There are large national differences in the rates and patterns of crime. Within Europe, overall crime rates in the UK are lower than those in the Netherlands but higher than those in the Scandinavian countries. Crimes of assault are more common in the USA and Australia (US Dept of Justice, 2004). National statistics are affected by local legislation, the recording of crimes, and by the conduct of legal proceedings.

Gender

Crime is predominantly an activity of young men. In England and Wales, 50% of all indictable offences are committed by males aged under 21 years, and 25% by those under 17 years. Men represent at least 80% of offenders (Monahan, 1997), and, in most Western countries, male prisoners outnumber female prisoners by 30:1. This gender difference is reflected in forensic mental health services, where the majority of patients are male.

Figure 24.1 Crimes reported to the British Crime Survey by the public during the period 1981–2003.

Ethnicity

Ethnic-minority groups are usually over-represented in prisoner populations. Minority groups are more likely to be poor, unemployed, and living in poor housing, all of which are risk factors for crime. Consequently, they are over-represented in forensic patient populations (Kaye and Lingiah, 2000).

Figure 24.2 Crimes recorded by the police and those reported to the British Crime Survey by victims of crime during the period 2002–2003. Some of the categories differ and drug offences are not included in the crime survey figures.

The high rates of arrests and convictions in ethnic-minority groups may also reflect discrimination at all stages of the criminal justice system—from stop and search through to trial and sentencing.

Victims

Most property crime is committed against strangers, but most serious interpersonal violence (rape, homicide, or child abuse) is committed by offenders known to the victim. Women are exposed to sexual violence from men in both developed and developing countries. Women and children are particularly at risk in developing countries during armed conflicts, where about 70% of casualties are non-combatants (Kennedy Bergen et al., 2005).

Victims of crime tend to be disadvantaged groups living in poorer parts of urban communities, so the mentally disordered are more likely to be victims of crime, and the risk is further increased as a consequence of their illness (Dean et al., 2007).

Causes of crime

Criminal behaviour (crime) needs to be distinguished from rule-breaking behaviour. Not all rule-breaking or socially unacceptable behaviour is criminal, nor is all criminal behaviour violent. In fact the vast majority is not, so general theories of the causes of crime will not necessarily address the causes of violence. Aggressive behaviour is not always violent, as it can be constrained by social rules. Violence is aggressive behaviour that transgresses social norms, as in street fighting as opposed to, for example, boxing.

Many factors determine whether an individual is aggressive in a particular situation. These include personality, the immediate social group, the behaviour of the victim, disinhibiting factors such as alcohol or drugs, general environmental factors such as noise and social pressure, physiological factors such as fatigue, hunger, and lack of sleep, and the presence of mental abnormality.

Genetic and physiological factors

Early studies of twins suggested that concordance rates for criminality were substantially greater in monozygotic twins than in dizygotic twins (Lange, 1931). Subsequent adoption studies in Sweden and Denmark have confirmed the genetic influence, but have shown that it is more modest than Lange supposed, and that it is mainly significant for severe and persistent criminality. Genetic factors are well established for conduct disorder in children, and the continuity in aggressive antisocial behaviour between childhood and adolescence is largely mediated by genetic influences (Eley et al., 2003). How genetic factors might mediate this increased risk is unclear, but it could involve hyperactivity and low IQ, both of which are risk factors in children for subsequent adult offending (Rutter, 2005).

The gender difference in offending has raised the question of the influence of either the Y chromosome or testosterone levels on offending. However, there is little evidence that chromosomal or hormonal abnormalities are causally associated with criminal behaviour or aggression. As was noted in Chapter 7, low brain 5-HT function has been associated with impulsive aggression. There is growing evidence that individuals with sociopathic personalities have long-standing neuropsychological deficits, particularly in executive processes (Raine et al., 2005).

Psychosocial factors

Individual psychological development interacts with social factors and cultural values to make offending more likely (see Table 24.1). Rule-breaking and antisocial behaviour often starts in childhood or early adulthood:

• Follow-up studies of delinquent young people show that early patterns of antisocial behaviour are likely to persist into adulthood.

• Delinquency is associated with harsh parenting and poverty.

• Exposure to physical abuse or neglect in childhood significantly increases the risk of violent offending in later life, for both men and women (Rutter, 2005).

The association between childhood adversity and violence may have several mechanisms. Abused and neglected children may have a heightened perception of threat from others. They may have decreased capacities to form successful interpersonal relationships, due to either decreased empathy for others, or reduced capacity for self-awareness. Alternatively, they may have a decreased capacity to manage arousal or regulate anger or anxiety arising from excessive exposure to fear experiences. It is also possible that children and parents simply share genetic factors that impair affect regulation or the ability to empathize. However, it is always important to consider the impact of resilience or vulnerability factors, such as temperament (Rutter, 2005).

Table 24.1 Psychosocial risk factors for offending

See Farrington (2000).

Psychiatric causes

A small but important group of offenders exhibit criminal behaviour which seems to be partly explicable by specific psychological or psychiatric abnormalities. This group particularly concerns the psychiatrist, and is discussed in the next section.

The association between mental disorder and crime

Frequency

The association between mental disorder and violence has been repeatedly demonstrated. Fazel et al. (2009) conducted a systematic review of violence and schizophrenia and other psychoses. This meta-analysis of 20 studies including 18 423 individuals found that schizophrenia and other psychoses were associated with violence (especially homicide). However, this risk was mediated by comorbid substance abuse, and was the same for individuals with substance abuse without psychosis.

From a large Danish birth cohort, Brennan et al. (2000) reported the following findings:

1. The risk of being arrested for a violent offence was significantly greater in both men (odds ratio 4.6), and women (odds ratio 23.2) who had been hospitalized for schizophrenia.

2. The risk of being arrested for a violent offence was also greater in men who had been hospitalized for organic psychosis (odds ratio 8.8).

3. Unlike Fazel, Brennan did not find that the increased risk could be explained by demographic factors or comorbid substance misuse.

4. Both men and women with a diagnosis of affective psychosis showed an increased risk of violent offending, but this could be accounted for by alcohol and substance misuse.

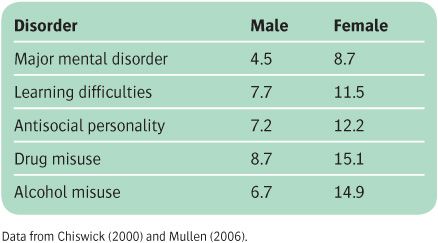

5. Alcohol and substance misuse by themselves are associated with a substantially increased risk of violent offending, as is antisocial personality disorder (see Table 24.2) (Chiswick, 2000).

Research on the prevalence and association of mental disorder in prisoners has recognized limitations:

• Not all criminals are brought to trial and found guilty.

• Not all criminals go to prison (potential sampling bias).

• Mentally disordered offenders may be diverted away from courts and prisons, or they may not be prosecuted.

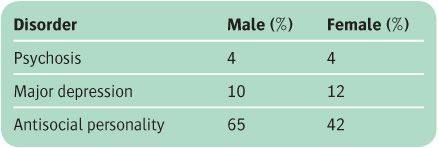

The proportion of prisoners with mental disorders is higher than the proportion of the general population with such disorders. In a meta-analysis of 62 psychiatric surveys of prisoners, Fazel and Danesh (2002) found that about one in seven had a treatable psychiatric illness (see Table 24.3). A larger number suffer from antisocial personality disorder.

The nature of the association

A causal relationship between mental disorder and crime is difficult to show empirically, especially if the type of crime is not defined. The finding that mentally disordered individuals are over-represented in prison does not necessarily mean that their mental disorder caused them to offend. Nor is criminal law-breaking an indicator in itself of mental disorder, no matter how heinous or bizarre the behaviour.

Table 24.2 The 1944–1947 Danish Birth Cohort Study: relative risk estimates of violent crime between 1978 and 1990

Table 24.3 Meta-analysis of 62 psychiatric surveys of prisoners

Only a small minority of all people who commit violent acts have serious mental illness such as psychosis. Swedish national registers linking hospital admissions and criminal convictions over 13 years demonstrated a population-attributable risk fraction of 5.2% (i.e. only 5% of convictions were accounted for by individuals with severe mental illness). This attributable risk fraction was higher in women across all age bands. In women aged 25–39 years, it was 14.0%, and in those aged 40 years or over, it was 19.0% (Fazel and Grann, 2006). The vast majority of patients with psychotic illnesses are no more dangerous than members of the general population. There is no evidence that homicidal behaviour is becoming more common in people with mental illness—indeed it appears to have been declining since the early 1970s (Large et al., 2008).

For a review of the association between psychiatric disorder and offending, see Chiswick (2000) (see also Box 24.2).

Specific psychiatric disorders

Substance dependence and crime

There are close relationships between substance abuse and crime which have substantially affected legislation, enforcement, and national policies (Grann and Fazel, 2004).

Alcohol and crime are related in three important ways:

1. Alcohol intoxication may lead to charges related to public drunkenness or to driving offences.

2. Intoxication reduces inhibitions and is strongly associated with crimes of violence, including murder.

3. The neuropsychiatric complications of alcoholism may also be linked with crime.

Offences may be committed during alcoholic amnesias or ‘blackouts.’ Blackouts are periods of several hours or days which the heavy drinker cannot recall, although at the time they appeared normally conscious to other people and were able to carry out complicated actions. However, the association is complex, and social factors related to drinking may be as important as alcohol itself. For a review, see Johns (2000).

Intoxication with drugs may lead to criminal behaviour, including violent offences. Drug misusers, especially those who are dependent on heroin and cocaine, commit repeated offences against both property and people in order to fund their drug habit. Some of the offences involve violence. Rates of drug abuse are increased among prisoners, and many succeed in obtaining drugs in prison. Involvement in criminal activity and with other criminals may lead to drug usage. For a review of the relationship between drug dependence and crime, see Johns (2000).

Learning disability

There is no evidence that most criminals are of markedly low intelligence. However, reduced intellectual ability is an independent predictor of offending (Holland et al., 2002).

People with learning disabilities may commit offences because they do not understand the implications of their behaviour, or because they are susceptible to exploitation by others. Property offences are the most common, but sexual offences are over-represented, particularly indecent exposure by males (Perry et al., 2002). The exposer is often known to the victim and therefore the rate of detection is high. There is also an association between learning disability and arson (Chiswick, 2000).

Mood disorder

Depressive disorder is sometimes associated with shoplifting. Severe depressive disorder may rarely lead to homicide. The depressed person may be deluded, for example, that the world is too dreadful to live in, and they consequently kill their family members in order to spare them. Suicide often follows. A mother suffering from postpartum disorder may sometimes kill her newborn child or her older children. Rarely, a person with severe depressive disorder may commit homicide because of a persecutory belief—for example, that the victim is conspiring against them. Occasionally, ideas of guilt and unworthiness lead depressed patients to confess to crimes that they did not commit.

Manic patients may spend excessive amounts of money on expensive objects, such as jewellery or cars, that they cannot pay for. They may be charged with fraud, theft, or false pretences. They are also prone to irritability and aggression, which may lead to offences of violence, although this is seldom severe.

Schizophrenia and related disorder

Psychotic illnesses may be associated with violence, especially when paranoid symptomatology is present, or the patient also has a substance abuse problem. Violence may occur because the offender is frightened, and self-control may be reduced by the presence of the psychotic state. Any state in which paranoid psychotic symptoms feature carries an increased risk of violent behaviour.

Epidemiology

Epidemiological studies have strongly suggested that schizophrenia is associated with an increased risk of both violent and non-violent offending (Brennan et al., 2000). This risk is substantially increased by substance misuse, but the proportion of violent crime attributable to schizophrenia is low (Fazel et al., 2009). A number of clinical risk factors for violence in schizophrenia have been proposed, including the following:

• fear and loss of self-control associated with non-systematized delusions

• systematized paranoid delusions, including the conviction that enemies must be defended against

• irresistible urges

• instructions from hallucinatory voices (command hallucinations)

• dual diagnosis, particularly substance misuse

• a strong negative affect (e.g. depression, anger, agitation).

Risk assessment is discussed on p. 729. Violent threats made by patients with psychosis should be taken very seriously (especially in those with a history of previous violence). Most serious violence occurs in those already known to psychiatrists, particularly if there is an identifiable victim.

Post-traumatic stress disorder

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may be related to offending in three ways:

• PTSD patients may abuse drugs and alcohol.

• PTSD is associated with increased irritability and decreased affect regulation.

• PTSD patients may rarely experience dissociative episodes involving violence, especially in circumstances resembling their original trauma. This is often hard to determine retrospectively.

PTSD has been the basis for psychiatric defences to homicide. Especially in cases of battered women with a history of prolonged trauma, occasional acts of retaliatory violence are not uncommon.

Morbid jealousy

The syndrome of morbid (pathological) jealousy (see p. 304) may be associated with several of the above diagnoses. It has been identified in 12% of ‘insane’ male and 3% of ‘insane’ women murderers. It is particularly dangerous because of the risk of the offence being repeated with another partner. It may sometimes be difficult to distinguish morbid jealousy from extreme possessiveness or control over women’s behaviour, which may be accompanied by violence, seen in some cultures.

Organic mental disorders

Delirium is occasionally associated with criminal behaviour, usually because of the associated confusion or disinhibition. Diagnostic problems may arise if the mental disturbance improves before the offender is examined by a doctor.

Dementia is sometimes associated with offences, although crime is otherwise uncommon among the elderly, and violent offences are rare. Violent and disinhibited behaviour may also occur after traumatic damage to the brain following head injury (Fazel et al., 2009). It may be difficult to distinguish the effects of post-traumatic neurological difficulties from post-traumatic psychological disorder.

Epilepsy

The association between epilepsy and crime is complex and poorly understood. While it has been widely believed that the risk of epilepsy is greater in prisoners than in the general population, a meta-analysis of seven studies indicated that this was not the case (Fazel et al., 2002), and a later meta-analysis of nine studies by Fazel et al. (2009) found some evidence of an inverse relationship between epilepsy and violence. Violent behaviour is sometimes associated with EEG abnormalities in the absence of clinical epilepsy, but it is doubtful whether this indicates a causal relationship (Fazel et al., 2009). Epileptic automatisms may, very rarely, be associated with violent behaviour and subsequent criminal proceedings. Violence is more common in the post-ictal state than ictally.

Impulse control disorders

DSM-IV contains a category ‘impulse control disorders not otherwise classified’ which brings together four speculative conditions relevant to forensic psychiatry—intermittent explosive disorder, pathological gambling, pyromania, and kleptomania. In ICD-10 these conditions are classified under abnormalities of adult personality and behaviour as ‘habit and impulse disorders.’ Whatever the clinical value of such classifications, none of these conditions has been established as a separate diagnostic entity.

Intermittent explosive disorder

This term is used to describe repeated episodes of seriously aggressive behaviour out of proportion to any provoking events and not accounted for by another psychiatric disorder (e.g. antisocial personality disorder, substance abuse, or schizophrenia). The aggression may be preceded by tension, followed by relief of this tension, which is in turn followed by remorse. The condition is rare, and many psychiatrists doubt whether it is a distinct psychiatric disorder.

Pathological gambling

Gambling is pathological when it is repeated frequently and dominates the person’s life, and persists when the person can no longer afford to pay their debts. The person lies, steals, defrauds, or avoids repayment in order to continue the habit. Family life may be damaged, other social relationships may be impaired, and employment put at risk.

Pathological gamblers have an intense urge to gamble, which is difficult to control. They are preoccupied with thoughts of gambling, much as a person dependent on alcohol is preoccupied with thoughts of drink. Increasing sums of money are gambled, either to increase the excitement or in an attempt to recover previous losses. If gambling is prevented, the person becomes irritable and even more preoccupied with the behaviour.

Similarities with the behaviour of people who are dependent on drugs have led to the suggestion that pathological gambling is itself a form of addictive behaviour. Brain imaging studies of pathological gamblers show abnormalities in mesolimbic reward pathways similar to those in drug dependence (Goudriaan et al., 2004).

The prevalence of pathological gambling is not known. It is probably more frequent among males. Most gamblers who are seen by psychiatrists are adults, but there is concern that young people are increasingly being involved, usually with gambling machines in amusement arcades. For a review of pathological gambling, see Dickerson and Baron (2000).

Pyromania

Pyromania refers to repeated episodes of deliberate fire-setting, which are not carried out for identifiable reasons such as monetary gain, to conceal a crime, as an act of vengeance, or as a consequence of hallucinations or delusions. Impaired judgement resulting from intoxication, dementia, or mental retardation also excludes pyromania, and the diagnosis is precluded by antisocial personality disorder, a manic episode, or (among children or adolescents) a conduct disorder. In the rare condition of pyromania, the act of fire-setting is preceded by tension or arousal, followed by relief. People with pyromania have a preoccupation with fires and firefighting, and enjoy watching fires. They may plan the fire-setting in advance, taking no account of the danger to other people caused by their actions. Some authors doubt the existence of pyromania as a diagnosis.

Kleptomania

Kleptomania refers to repeated failure to resist impulses to steal objects that are not needed, either for use or for their monetary value. The impulses are not associated with delusions or hallucinations, or with motives of anger or vengeance. Before stealing there is increased tension, which the stealing relieves. The diagnosis is excluded by associated antisocial personality disorder, a manic episode, or (among children or adolescents) a conduct disorder, or when the stealing results from sexual fetishism. The objects stolen may be of little value and could have been afforded; they may be hoarded, thrown away, or later returned to the owner. The patient knows that the stealing is unlawful, and may feel guilty and depressed after the immediate pleasurable sensations that follow the act.

Kleptomania occurs more often among women. Associations with anxiety and eating disorders have been described. It may be sporadic with long intervals of remission, or may persist for years despite repeated prosecutions. Some authorities doubt its existence as a separate syndrome, pointing out that diagnosis depends entirely on accused individuals’ descriptions of their own motives.

Specific offender groups

Female offenders

Women are more law-abiding than men. Shoplifting accounts for 50% of all their convictions, and violent and sexual offences are uncommon.

Men and women are treated differently by the criminal justice system. Women are sentenced more leniently for similar offences, and they are more likely to be viewed as ‘sick.’ Psychiatric disorder is frequent among women admitted to prison, with personality disorder and substance misuse being especially common (Fazel and Danesh, 2002), and self-harm before and during imprisonment is also common (Jenkins et al., 2005).

A ‘premenstrual syndrome’ was sometimes proposed by defence lawyers, but this rarely happens now. Premenstrual symptoms may complicate or exacerbate pre-existing social and psychological difficulties, but there is no evidence that they are a primary cause of offending.

Young people

National crime statistics indicate that increasing numbers of people under 18 years of age are involved in criminal behaviour. In Scotland, for example, in the year 2000, 34% of young people (aged 12–15 years) reported committing a criminal offence in the previous year, compared with 22% in 1992 (Scottish Executive Central Research Unit, 2002). Where a young person engages in serious interpersonal violence, the victim is often well known to them, and is commonly a family member. Serious violence by young people and children is rare, and the individuals involved have frequently been the recipients of violence themselves, both within and outside their families (Hamilton et al., 2002).

Ethnic minorities

Some ethnic groups are over-represented as offenders in the criminal justice system, and also in forensic psychiatric services. Non-white patients may be more likely to receive diagnoses of mental illness, with individual personality difficulties being overlooked. People from ethnic minorities may be discriminated against in the criminal justice system. People of African Caribbean origin have higher rates of imprisonment in the UK, but lower rates of psychiatric morbidity (Coid et al., 2002). This contrasts with the excess of African Caribbeans in secure hospitals, which suggests that those offending while mentally ill are more likely to be admitted to hospital.

Psychiatric aspects of specific crimes

The following sections are concerned with the types of offences that are most likely to be associated with psychological factors. These are crimes of violence, sexual offences, and some offences against property.

Crimes of violence

Violence among mentally abnormal offenders is more strongly associated with personality disorder than with major mental illness. It is particularly common in people with antisocial personality traits who misuse alcohol or drugs, or who have marked paranoid or sadistic traits. It is often part of a persistent pattern of impulsive and aggressive behaviour, but it may be a sporadic response to stressful events in ‘over-controlled’ personalities. The assessment of dangerousness and the management of violence are discussed on p. 729.

Homicide

Most jurisdictions recognize different categories of homicide, according to the degree of intention and responsibility shown by the perpetrator. In the USA, defendants may be charged with different ‘degrees’ of murder. In England and Wales, there are three ‘legal categories’ of homicide—murder, manslaughter, and infanticide—and murder and manslaughter are defined by historical precedent, not by statute.

Manslaughter covers unlawful homicides that are not murder. It is customary to distinguish between voluntary and involuntary manslaughter. In voluntary manslaughter, the defendant may have malice aforethought, but mitigating circumstances reduce their crime. In involuntary manslaughter, there is no malice aforethought; it includes, for example, causing death by gross negligence.

Normal and abnormal homicide

Mental disorders may count as mitigation for an individual charged with murder, reducing the charge to manslaughter. Homicide can be divided according to the legal outcome into normal (murder or common-law manslaughter) and abnormal (insane murder, suicide murder, diminished responsibility, or infanticide).

Normal homicide accounts for half to two-thirds of all homicides in the UK, as in other Western countries, even in the USA, where the overall homicide rate is much higher. It is most likely to be committed by socially disadvantaged young men. In the UK, the victims are mainly family members or close acquaintances. In countries with high homicide rates, a greater proportion of killings are associated with robbery or sexual offences. Sexual homicide may result from panic during a sexual offence. Alternatively, it may be a feature of a sadistic killing, sometimes committed by a shy man with bizarre sadistic and other violent fantasies.

Abnormal homicide accounts for one-third to half of all homicides in the UK. It is usually committed by older people. The victims of abnormal homicide are often family members. The most common psychiatric diagnoses are psychoses, substance use disorder, and personality disorder (Fazel and Grann, 2004). Depressive disorder can also be involved, especially in those who kill themselves afterwards. Homicide by women is much less frequent than that by men, but is nearly always ‘abnormal.’

A large proportion of all murderers are under the influence of alcohol at the time of the crime, and drug misuse is also an important factor.

Multiple homicide

Multiple murders are rare, although they attract great public attention. They include:

• individuals without mental illness who kill several people at once, sometimes a family killing which is often followed by suicide. Paranoid and grandiose character traits are common (Mullen, 2004)

• killings attributable to a psychotic illness in which the killer aims to save himself or his family from a perceived threat

• serial killings that take place over a period of time. These may be ‘normal’ (e.g. killings by terrorists) or ‘abnormal’ (e.g. psychotic, or motivated by sexual sadism or necrophilia).

Homicide followed by suicide

Homicide followed by suicide accounts for about 50 deaths in the UK annually, while in the USA the comparable figure is 1000–1500 (Chiswick, 2000). An epidemiological survey of 180 victims and 147 perpetrators in the UK reported the following findings (Barraclough and Harris, 2002):

• Around 80% of the incidents involved one victim and one perpetrator.

• Around 88% of the incidents exclusively involved members of the same family.

• Around 75% of the victims were female, while 85% of the perpetrators were male.

• The victims of the male perpetrators were nearly always current or previous female partners and their children, while the victims of female perpetrators were predominantly their children.

• A few men kill strangers and then themselves. Such individuals are usually young (under 35 years of age) and may be psychotic or more commonly have paranoid and narcissistic traits and take revenge for trivial or imagined slights or humiliations (Flynn et al., 2009).

Parents who kill their children

Around 25% of all victims of murder or manslaughter in the UK are under the age of 16 years, and babies under the age of 1 year are at the highest risk of all age groups (Breslin and Evans, 2004). Most children are killed by a parent who is mentally ill, usually the mother. The classification of child murder is difficult, but useful categories are mercy killing, psychotic murder, and killing as the end result of battering or neglect (D’Orban, 1979). This last category is most common.

Infanticide

A woman who kills her child may be charged with murder or manslaughter. English law recognizes a special category, infanticide, where the child is under 12 months of age. Infanticide is treated as manslaughter with less harsh penalties, and the same freedom of sentencing as for manslaughter. The English legal concept of infanticide is unusual, as it is only required that the woman’s mind was disturbed as a result of birth or lactation, not that the killing was a consequence of her mental disturbance.

Fewer than five cases a year are recorded in the UK. Infants are most at risk on the first day of life, and the relative risk decreases steadily to that of the general population by 1 year. Fathers are slightly more likely to be recorded as the prime suspect over time. Mothers have received less severe sentences than fathers. Puerperal psychotic illness is a relatively infrequent cause of homicide, and depression is a factor in some cases. Later infant homicides are usually due to fatal child abuse. Infanticide has been strongly associated with motherhood at a young age.

Family homicide

Another useful way to distinguish homicides is in terms of the relationship between perpetrator and victim. Most serious violence takes place within the family (25% of all homicide victims are aged under 16 years, and 80% are killed by their parents). Most homicide perpetrators know their victims well; around 50% of the female victims of homicide are wives or partners of the perpetrator, and the rest are often friends or relatives.

Domestic violence

Domestic violence accounts for about 25% of all violent incidents measured by the British Crime Survey. In England and Wales there are about one million incidents of domestic violence annually, about two-thirds of these against women. Most batterers do not have either a diagnosable mental disorder or a criminal history. However, heavy drinking is common.

Some people are violent only within their family, while others are also violent outside the family. Violence in the family can have long-term deleterious effects on the psychological and social development of the children and on the mental health of the partner (see Chapter 8).

Violence in the family may also be directed towards children (child abuse is reviewed on p. 674) and towards elderly relatives (elder abuse is referred to on p. 497). Any of these forms of violence may rarely result in homicide.

Alertness to possible domestic violence is required not only in Accident and Emergency departments, but also in primary care and in obstetric and paediatric clinics. Intervention is difficult and raises ethical issues (see Table 24.4).

Violence towards partners

Violence by men towards their female partners is much more frequent than violence by women towards their male partners, is physically more serious, and is more often reported. Most ‘wife batterers’ are men with aggressive personalities, while a minority are violent only when psychiatrically unwell, usually with a depressive disorder. Other common features among these men are morbid jealousy and heavy drinking. Such men may have suffered violence in childhood, and often come from backgrounds in which violence is frequent and tolerated. Behaviour by the victim may contribute to or provoke (but not justify) violence, but this is difficult to assess if only the perpetrator is interviewed. However, when battering is seen as a ‘joint’ problem, the batterer may have less incentive to stop. Repetitive battering, especially in the context of jealousy, is a real risk factor for homicide.

Table 24.4 Ethical and legal issues: domestic violence

Sexual offences

Sexually violent offences

In the UK, sexual offences account for less than 1% of all indictable offences recorded by the police, but account for a significant proportion of offenders referred to psychiatrists. However, only a small proportion of people who are charged with sexual offences are assessed by psychiatrists. Most sexual offences are committed by men.

Sexual offenders are generally older than other offenders, and reconviction rates are generally lower. The minority of recidivist sexual offenders are extremely difficult to manage (see Box 24.3). In the UK, Part 1 of the Sex Offenders Act 1997 requires those convicted or cautioned for relevant sex offences to be kept by police on the Sex Offender Register.

The most common sexual offences are indecent assault against women, indecent exposure, and unlawful intercourse with girls aged under 16 years. Some sexual offences do not involve physical violence (e.g. indecent exposure, voyeurism, and most sexual offences involving children); others may involve considerable violence (e.g. rape). The nature and treatment of non-violent sexual offences are discussed in Chapter 14, but their forensic aspects are considered here. For a review, see Gordon and Grubin (2004).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree