Figure 19.1. Causes of gastrointestinal bleeding. A). Esophageal varices. B). Crohn’s Disease.

19.2.2 Gastroparesis

Introduction

Literally, gastroparesis means “stomach paralysis”. Gastroparesis is a syndrome defined by delayed gastric emptying essentially of solids, without evidence of mechanical obstruction. When the stomach works normally, gastric contraction helps to grind the ingested food and then propels the pulverized food into the small intestine, where digestion and absorption of nutrients continue.

The clinic of gastroparesis may range from mild forms, in which the patient reports dyspeptic symptoms such as early satiety, postprandial fullness or nausea, to severe forms with gastric retention that manifests as repeated vomiting, even with significant nutritional impairment.

Etiology

Although there are several causes leading to gastroparesis, one of the most common is diabetes, but there are also infections, endocrine disorders, connective tissue disorders like scleroderma, neuromuscular diseases, idiopathic causes (unknown) cancer, radiation treatment to the chest or abdomen, some forms of chemotherapy, and surgery of the upper intestinal tract.

Any surgery performed in the esophagus, stomach and duodenum may result in vagus nerve injury, which transmits sensory and motor responses (muscle) to the intestine: normally, the vagus nerve sends impulses through neurotransmitters to the stomach smooth muscle to produce contractions and propel gastric contents. If the vagus nerve is injured during surgery, gastric emptying may not occur. Symptoms of postoperative gastroparesis may develop immediately or years after surgery.

On the other hand, the use of some medications, especially narcotics for pain control with calcium channel blockers and some antidepressants, may delay gastric emptying and gastroparesis-like symptoms (Table 19.3). People suffering from eating disorders like anorexia and bulimia may also develop gastroparesis. Fortunately, gastric emptying can be restored and symptoms improve, while normalizing food intake and improving eating habits and feeding schedules.

|

Table 19.3. Drugs preventing gastric emptying.

19.2.3 Gastrokinetic-prokinetic Agents

In many patients with gastroparesis, prokinetic agents accelerate gastric emptying and improve nausea, vomiting and postprandial fullness sensation.

Metoclopramide

Metoclopramide was the first drug developed as a prokinetic and antiemetic agent. It has a D2 antidopaminergic action and is also a serotonin 5-HT4 receptor agonist. It acts on dopamine receptors in the stomach and intestine, as well as in the brain. By stimulating stomach contractions, it promotes better emptying. It can act on the part of the brain responsible for controlling the gag reflex, and therefore may reduce the sensation of nausea and the urge to vomit.

For some people, the use of this medication is limited owing to the side effects of agitation and facial spasms or tardive dyskinesia. Metoclopramide can also cause painful swelling of the breast and nipple discharge in both men and women. It is not recommended for long-term use. The recommended dose is 10 to 20 mg every 8 h orally, about 20 minutes before meals.

Domperidone

Domperidone also has an antidopaminergic action, but with the advantage that very little crosses the blood-brain barrier, so it has far less side effects at the central level. Chronic administration of domperidone can improve gastric dysrhythmia, which correlates with clinical improvement, but is not accompanied by significant changes in gastric emptying, thus suggesting the existence of an electromechanical dissociation. The recommended dose is 10 to 20 mg every 8 h orally, about 20 minutes before meals.

Erythromycin

Erythromycin, an antibiotic of the macrolide family, acts as a potent gastrokinetic agent and a motilin receptor agonist on intestinal smooth muscle. Intravenous erythromycin is followed by a normalization of gastric emptying of both solids and liquids; a beneficial effect persists with oral erythromycin but is much less than after parenteral administration.

The effectiveness of erythromycin in the long-term treatment of gastroparesis is controversial, since it seems to be accompanied by a progressive loss of efficiency, probably due to a tachyphylactic effect. Moreover, erythromycin has side effects such as ototoxicity in patients with renal failure or pseudomembranous colitis, which sometimes lead to discontinuation of its administration. Another fact to consider is that the use of this antibiotic as a prokinetic agent carries the risk of inducing bacterial resistance. The recommended intravenous dose in acute cases is 3 mg/kg every 8 h. The oral dose is 250-500 mg every 8 hours, about 20 minutes before each meal.

Cisapride

Cisapride, a serotonin 5-HT4 receptor agonist, and to a lesser extent, a serotonin 5-HT3 receptor agonist, is another drug frequently used in the treatment of gastroparesis. Its administration, both oral and intravenous, enhances gastric emptying of digestible and indigestible solids.

It binds to serotonin receptors in the stomach wall, leading to contraction of the smooth muscle of the stomach and improvement in gastric emptying. At the end of 1990s, cisapride was withdrawn from the market due to reported complications of cardiac arrhythmias in patients with a history of arrhythmia or coronary artery disease who used this drug. Now, it is once again available, though its use is restricted. People who have underlying kidney or heart disease should not take cisapride.

19.2.4 Diarrhea

Diarrhea is a symptom typical to many pathological conditions, especially in diseases of the GI tract. It is a consequence of an alteration in GI mechanisms involved in the absorption and secretion of fluids, electrolytes and nutrients.

Etiology

Diarrhea is common in ICU patients, and its incidence is estimated between 20 and 60%. All medical staff associate diarrhea in the ICU with tube feeding, but not always does the cause reside in the process of feeding or schedule. The main factors associated with diarrhea in the ICU are drugs (antibiotics, antacids, with magnesium and others), intestinal mucosal injury, bacterial or viral infection, and the administration of large volumes of hyperosmolar liquid preparations directly into the small intestine.

The causes of acute diarrhea are variable and can be classified in different ways, one of which is infectious (viral, bacterial, parasitic and fungal) and non-infectious.

The majority of enteric pathogens that cause acute diarrhea penetrate the body through the oral route and colonize the intestine before the onset of symptoms of diarrheal disease. A key step in the colonization process, in almost all cases, is bacterial adherence to the intestinal epithelium. Often, the mechanisms of adhesion of bacteria and protozoa are very specific and are mediated by interactions of receptor-ligand type. This process often uses lecithins or similar molecules (adhesins) which interact with hydrocarbon fractions of the membrane of the microvilli. The mechanisms by which enteropathogens cause diarrhea are various, but two broad categories are distinguished: those increasing intestinal secretion; and those reducing intestinal absorption.

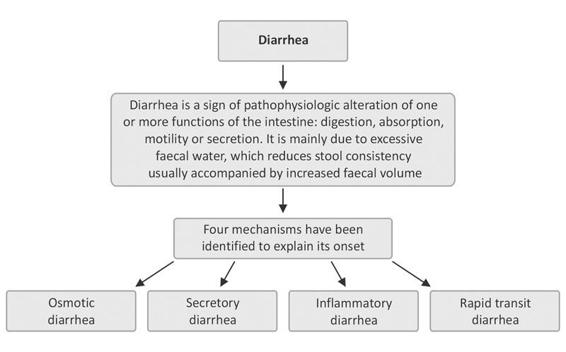

Figure 19.2. Types of diarrhea.

Diagnosis

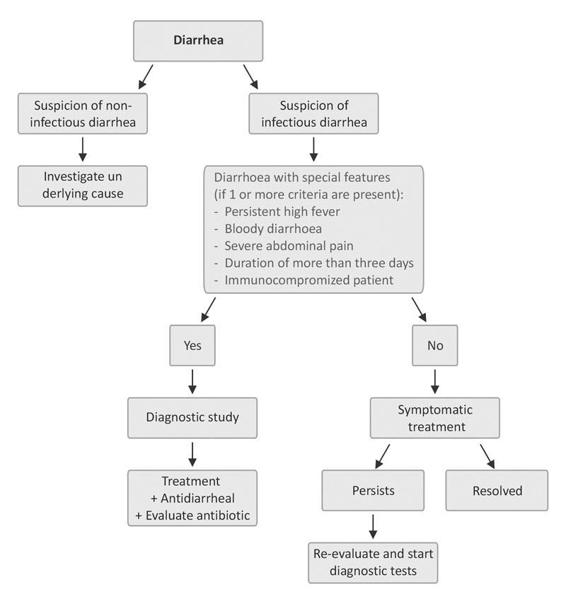

For acute diarrhea, the most common diagnosis is established on the basis of the clinical history and features without recourse to other examinations. The latter may be indicated in severe processes or when the patient may be at increased risk (elderly, immunocompromised, etc.). In such cases, the most important diagnostic test in acute diarrhea is microbiological analysis of stool, usually culture for enteropathogenic bacteria and direct examination of the stool sample under optical microscopy to rule out the presence of parasites. It may be necessary to repeat this study to rule out with certainty the presence of pathogenic microorganisms (disease-producing pathogens). Figure 19.3 summarizes the management of acute diarrhea.

Figure 19.3. Flow chart of the management of acute diarrhea.

The study of a patient with chronic diarrhea can be daunting. Based on the multiple triggering causes, several laboratory tests could be described. However, the basis for establishing the diagnosis is a complete and thorough medical history, along with physical examination. At the beginning, even simple analytic studies such as blood testing can be ordered. With this information we can establish the mechanisms involved, direct causes, and nutritional and hydration status of the patient, the latter being key to treatment. At first, and depending on the suspected diagnosis, other investigations may be indicated, such as a fasting test (to demonstrate lactose intolerance), an examination of the large intestine by endoscopy (proctosigmoidoscopy in cases of suspected irritable bowel syndrome), colonoscopy, stool microbiology.

Other suitable tests include determining the fat (maldigestion or fat malabsorption), blood, leukocytes or laxative content of the stool. The presence of blood and leukocytes (inflammatory cells) suggests an inflammatory process, underlining the importance of microbiological examinations. Imaging studies such as upper GI endoscopy or radiological examination of the small intestine can also be useful.

19.2.5 Nutrition in Neurocritical Patients With Gastrointestinal Problems

The quality of nutrition plays an active role in everyday activities, emotional reactions, affectivity, as well as genesis of the cognitive substrate. Every year, thousands of people suffer serious head injuries with devastating effects on neurological function and the consequent deterioration in their quality of life. For four decades, advances in nutritional support in critically ill patients were not applied to severe neurosurgical patients, and, despite the predictability of the impact that these injuries have on body homeostasis and the profound metabolic effects on the hematopoietic, immune and muscular systems, treatment consisted of waiting, sometimes delaying for weeks the initiation of nutritional support.

Today, many studies on early nutritional support in severe neurosurgical patient suggest that early nutrition can lower the risk of infection and death of the neurologic patient.

Early or Late?

The critically ill patient requires early nutritional support which attenuates the physiological response to illness, so as to decrease the progression of multiple organ failure (MOF) with the adequate and early administration of food and to reduce metabolic complications and infections. Previous studies had shown that early nutrition lowers the risk of morbidity due to superinfection. However, while starting early enteral or parenteral support is not sufficient, it does provide an adequate supply of energy intake to cover the energy needs of these patients.

Enteral or Parenteral?

In any patient in critical condition, treatment will aim to reducing the risk of intestinal atrophy and bacterial translocation, for which enteral nutrition has become the main strategy to stimulate mucosal trophism. This principle is important and in most protocols enteral nutrition is included as an essential part of treatment. Sometimes, it is difficult to achieve caloric needs enterally early due to serious disorders in intestinal transit as a result of ECT and intracranial hypertension; therefore, the benefits of early nutrition are lost. This is especially true for gastric feeding, because gastroparesis is much longer than jejunal ileus.

Some studies, such as that by Young et al. suggest a better prognosis for patients fed with parenteral nutrition. The development of naso-esophageal probes, the early use of endoscopic gastrostomy, the use of new and improved prokinetic agents [Altmayer et al., 1996] and the basic formulas that favour absorption [Taylor et al., 1999] have improved the use of the enteral route, increasingly diminishing dependency on the parenteral route to supply the calories needed. Initially, it is recommended to start nutrition as soon as the patient has been revived and is hemodynamically stable.

Unless there are formal contraindications or an overt intolerance is documented, enteral nutrition is the technique of artificial nutrition of choice. This concept is applicable to any patient, even to gastroenterological patients. If a portion of the GI tract is functional, it must be used: enteral nutrition is more physiological, and brings more benefits to the patient’s recovery, while aiming to quickly reach the resting energy expenditure. Parenteral support can be gradually decreased as enteral nutrition is increased.

Uncontrollable diarrhea with dehydration and/or electrolyte imbalance, or acute GI bleeding may preclude enteral nutrition. As a second step, parenteral nutrition can be initiated as soon as possible to prevent depletion.

In enteral nutrition, the route and the quantity of calories needed for the patient’s energy expenditure should be determined. As the symptoms of diarrhea or bleeding decrease, the possibility of initiating enteral nutrition or mixed nutrition should be considered in order to gradually discontinue enteral nutrition.

In general, the frequency of potentially serious complications is greater with parenteral nutrition than with enteral nutrition. Until recently, the fundamental difference between them was the risk of catheter sepsis in parenteral nutrition. Although the risk is ultimately minimized, there are still differences in morbidity favouring enteral nutrition, especially with regard to metabolic disorders or liver problems related to artificial nutrition, which are more frequent and severe with parenteral nutrition.

Schedules

A naso-esophageal probe should be placed and an oligomeric formula started where the size of the macronutrient polymer is lower. Its use is indicated in cases of lower digestion or absorption capacity. Protein intake is provided as dipeptides and tripeptides and a very small portion of tetrapeptides and pentapeptides, keeping very limited the incorporation of amino acids, in addition to high osmolarity that they give to the formula, for the proper absorption of dipeptides and tripeptides.

These formulas contain a significant proportion of medium-chain triglycerides. Carbohydrates are supplied, as in the polymers, in the form of maltodextrin. In addition, the formula must be enriched with arginine, ribonucleotides and omega 3 fatty acids. Enteral nutrition should be started at low infusion volumes and then gradually increased, as tolerated, until all calorie supplements can be supplyied by this route.

Nutritional Monitoring

Once the nutritional regimen has been initiated, the physician will need to know the extent to which repletion of body behaviours considered strategic occurs to ensure the success of pending medical-surgical action. Nutritional monitoring should serve as a feedback mechanism for changes in the scheme of nutritional support if the patient fails to respond as expected.

19.2.6 Conclusions

One of the most common problems in critically ill patients is GI complications during the stay in the ICU. The most clinically relevant complications include GI bleeding and complications associated with enteral feeding. Currently, GI bleeding is uncommon thanks to the use of mucosal protective agents and the increasingly widespread use of enteral nutrition. A common complication of enteral nutrition is diarrhea, which may result from improper use of formula or patient intolerance to the type of formula given. Furthermore, some medications such as sorbitol can cause diarrhea. GI complications have a negative effect on the amount of diet that can be provided to the patient. This nutritional deficiency can also adversely affect patient outcome, with an increase in infectious complications, hospital stay and mortality. The use of protocols for the identification and proper management of GI complications in critically ill patients may be a beneficial factor in their evolution.

General References

Part I: “Gastrointestinal Motility Disorders in the Neurocritical Patient”

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree