Introduction

The generalized convulsive seizure has been known since antiquity, and the earliest descriptions appear in Egyptian hieroglyphics before 700 BC.48 From the mid-19th century, the generalized convulsive seizure was considered the cardinal manifestation of genuine or idiopathic epilepsy caused by a predisposition to have seizures. The generalized convulsive seizure was described as grand mal,26 a term that is still encountered. Whereas a great amount of literature has been dedicated to this seizure type, which corresponds to the generalized tonic-clonic seizure (GTCS), the distinction between GTCS and purely generalized clonic seizure (GCS) did not appear clearly before the mid-20th century. The first use of this distinction was in the original international classification of epileptic seizures proposed by the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE),23 in which they were a type of generalized convulsive seizure different from the tonic–clonic, myoclonic, and tonic seizures. They were considered as observed especially in children.

In the same classification, the authors described a category of unilateral seizure including unilateral clonic seizures, also known as hemiclonic seizures (HCS), occurring almost exclusively in very young children. The existence of unilateral motor seizures with possible permanent hemiplegic sequelae, if the seizures are prolonged, has long been recognized.4,17,26,37,47,51 However, the combination of seizure observation and recording and the study of a large series of cases with status epilepticus (SE), with or without hemiplegia and/or permanent epilepsy, enabled Gastaut et al.22 to define precisely the electroclinical details of these unilateral seizures.

Definitions

These two seizure types, GCS and HCS, were better defined in the 1970 proposal.19 The generalized seizures were “those in which the clinical features do not include any sign or symptom referable to an anatomical and/or functional system localized in one hemisphere and usually consist of initial impairment of consciousness, motor changes which are generalized or at least bilateral and more or less symmetrical and may be accompanied by ‘en masse’ autonomic discharge; in which the electroencephalographic patterns from the start are bilateral, grossly synchronous and symmetrical over the two hemispheres; and in which the responsible neuronal discharge takes place, if not throughout the entire grey matter, then at least in the greater part of it and simultaneously in both sides.”19

The unilateral seizures were “those in which the clinical and electroencephalographic aspects are analogous to those of the generalized group, except that the clinical signs are restricted principally, if not exclusively, to one side of the body and the electroencephalographic discharges are recorded over the contralateral hemisphere. Such seizures apparently depend upon a generalized or at least very diffuse neuronal discharge which predominates in, or is restricted to, a single hemisphere and its subcortical connections. They are characterized by clonic, tonic or tonic–clonic convulsions, with or without an impairment of consciousness, expressed only or predominantly in one side. Such seizures sometimes shift from one side to the other but usually do not become symmetrical.”19

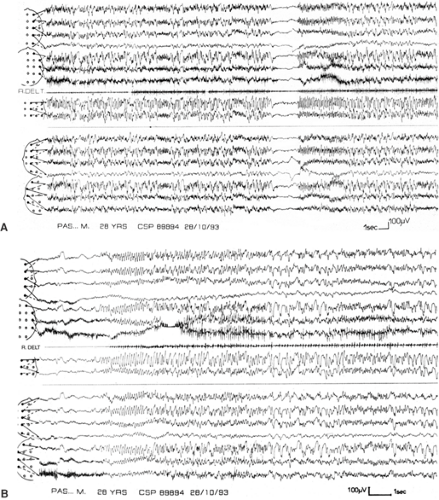

One epileptic clonic seizure is a form of generalized seizure peculiar to early childhood and characterized by (a) clinical loss of consciousness, one massive autonomic discharge, and more or less rhythmically repeated, bilateral clonic contractions, distributed more or less regularly throughout the entire body; (b) an associated mixture of rapid rhythms and slow waves realizing more or less regular images of spike-and-waves and polyspike waves in the electroencephalogram (EEG).20

However, 11 years later, the ILAE commission, in a new proposal, maintained the category of GCS, but withdrew that of unilateral clonic seizures (as well as all other unilateral seizure types), deeming them “putative syndromic seizures.”8 The definition of generalized seizure has changed. These seizures are now defined as “those in which the first clinical changes indicate bilateral involvement of both hemispheres. Consciousness may be impaired and this impairment may be the initial manifestation. Motor manifestations are bilateral. The ictal electroencephalographic patterns initially are bilateral, and presumably reflect neuronal discharge which is widespread in both hemispheres.”8

Finally, the last ILAE commission has proposed a completely new approach to the seizure classification, which can be found at its Web site (www.ilae-epilepsy.org). The glossary now defines generalized seizure to mean “a seizure whose initial semiology indicates or is consistent with more than minimal involvement of both cerebral hemispheres.” In the list of seizure types, generalized clonic seizures are not described, and the hemiclonic seizures are placed among focal seizures with no additional description.

In the semiologic classification proposed by Lüders et al.,30 based on a purely clinical description of the seizures, the definitions are the same but expressed differently. Clonic seizures are simple motor seizures, consisting of a series of myoclonic contractions that regularly recur at a rate of 0.2 to 5 per second. Their different subtypes are indicated by the use of “modifiers.” These seizures are generalized when the manifestations occur over a relatively widespread distribution, with approximately equal involvement of both sides and of the distal and proximal segments of the brain. These seizures may also be localized; in that case, different modifiers are used according to the somatotype localization, such as “left-hand clonic seizure.” Unilateral seizures are not considered in this classification. Hemiclonic seizures may be described as “unilateral, left or right clonic seizures” or “left or right hemibody clonic seizures.”

These variations reflect our lack of knowledge of the true physiopathology of generalized and unilateral seizures, despite the progress in technical advances in all fields of investigation. In practice, no clear-cut borderline exists between generalized and unilateral clonic seizures in many cases, making it difficult, if not impossible, to classify them. Moreover, the two types can have a focal onset that is often hidden because of the rapid secondary generalization. Sometimes the generalized clonic seizure can begin with a very short tonic phase, but continue with all the characteristics of the purely clonic seizure. Outside of cases of SE, these seizures are not usually observed by the clinician, and most onlooker descriptions are not detailed enough to definitively classify them as generalized or unilateral in an infant or a young child. The observation of a postictal hemiparesis is in favor of ictal unilaterality.

As in GTCS, clonic and hemiclonic seizures may be an isolated event in the setting of an acute encephalopathy, a symptom of serious brain disease, or a manifestation of several epilepsy syndromes of differing prognoses.

Epidemiology

GCSs and unilateral clonic seizures or HCSs are rarely described in the literature, and they are not considered apart from GTCSs in epidemiologic studies. However, GCSs are probably rare, unlike HCSs, which are reported primarily in papers concerning the pediatric population because of their relative frequency in infancy and childhood.

In one single Spanish study,36 GCSs are not specified, but the following data were reported for unilateral seizures, without distinction between HCSs and the other types: Among 5,000 patients consecutively recruited between1966 and 1990, 346 (6.92%) presented with unilateral seizures; 13.29% of them were febrile seizures and 18.21% developed during status; 53.17% started before 2 years, 80% before 6 years and only 2.02% after 18 years. The unilateral seizures were the initial seizures of generalized epilepsies in 7.5% of the patients, of focal epilepsies in 23.4%, and of undetermined epilepsy if generalized or focal in 65.9% (the majority).

In a previous series of 3,000 patients,35 the same author found 151 patients (5%) with HCSs, separated into four groups. In the first group, 39 patients went on to a diagnosis of temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE). In the second group, 32 patients had Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (it is important to note that severe myoclonic epilepsy was not recognized as an epilepsy type in this study). In the third group, six patients had an idiopathic generalized epilepsy. In the fourth group, 74 patients had only HCSs.

In a pediatric French regional population-based study,31 GCS had an incidence of 5.8 per 100,000 children younger than 10 years, in comparison with 8 per 100,000 with GTCS. HCSs were not counted because they did not appear in the 1981 international classification. Conversely, HCSs appeared in a pediatric Yugoslavian regional population-based study42 in which they represented 6% of patients born between January 1, 1967 and December 31, 1984, aged less than 18 years, versus 0.3% for GCS and 38.8% for GTCS.

One could also indicate that, due to their propensity manifest during SE, HCSs have been often considered within epidemiologic studies of SE, whereas generalized clonic statuses are rarely separated from generalized tonic–clonic seizures. Thus, Aicardi and Chevrie,1 among 239 cases of SE, reported 102 cases with GCS status and 94 with HCS status. Congdon and Forsythe9 reported 17 cases of SE treated by clonazepam, in which 14 were GCS status but none HCS status.

Clinical Features

Generalized Clonic Seizures

All authors recognize that clonic seizures are predominantly observed in infants and children, and very often tend to be lateralized. So, the descriptions usually given correspond to HCSs or GCSs evolving to HCSs or vice versa. We did not find many descriptions of seizures that were only generalized. In 1973, Gastaut20 defined their characteristics: “Loss of consciousness, massive autonomic discharge, and bilateral clonic contractions more or less rhythmically repeated and more or less irregularly distributed in all the body parts. The ictal EEG shows a mixture of rapid rhythms and slow waves realizing more or less regular images of spike-waves and polyspike-waves.”

A good description was reported by Gastaut and Broughton.21 The attacks begin with loss of consciousness associated either with sudden hypotonia or, conversely, with a brief generalized tonic spasm, sometimes so abbreviated that it could be considered as massive bilateral myoclonus. Either causes falling. The child then remains on the floor for 1 minute or longer and is seized by a series of bilateral myoclonus, usually generalized, although often asymmetrical and predominating on one side or in one limb. Subsequently, the variability of amplitude, frequency, and spatial distribution of these jerks from one moment to the next may become quite extraordinary. The most unlikely combinations are observed. Rapid low-amplitude twitching of facial muscles, for example, may be associated with infrequent but very intense jerks of the upper limbs and with such rapid myoclonus of the lower limbs that virtual tetanic contraction results. In some children, particularly those 3 years of age or younger, the myoclonus remains bilaterally synchronous and massive throughout the attack, rather than showing such complex and unstable patterns. The autonomic changes are relatively unimportant, except during very prolonged seizures in which accumulated bronchial secretions may cause respiratory distress. Resumption of consciousness is rapid after brief seizures. Those of long duration, however, may be followed by a confusional or even comatose state with generalized muscular hypotonia and areflexia.

Other forms of clonic seizures, seen in older subjects, are more properly considered as absence status with marked myoclonus, often rhythmic, or prolonged myoclonic absences with the jerks repeated at 3 Hz.

Hemiclonic Seizures

Conversely, HCSs have been well studied. Here we report their description by Roger et al.,43 completed by our own observations.

When observed, the onset is variable. Sometimes HCSs present as repeated clonic jerks or twitching of the eyeballs, followed by a deviation of the head to the same side. These are followed rapidly by hemifacial myoclonus that spreads to the upper and lower limbs. In other cases, the clonic jerks involve the entire side from the onset. In some cases, the clonic phase is preceded by a general discomfort, with abdominal pain, pallor, and loss of contact. Many children are discovered while already convulsing. More often, the seizures are of long duration (minutes, hours, even days). In such cases, the jerks show continuous changes in frequency, rhythm, and amplitude in the different body areas involved. This gives a pattern of erratic seizures. They may, for instance, disappear in the lower limb while continuing in the upper limb or the face, and then spread to the entire side of the body again, thereby

creating patterns of considerable complexity. At times they affect both sides of the body, either simultaneously as generalized seizures, or successively, as alternating epileptic seizures, so-called “see-saw epileptic seizures” or crises à bascule. They also can affect one upper limb and the opposite lower limb together, as crossed seizures. Another eventuality consists of a seizure reduced for some minutes to the loss of consciousness with only slight jerks localized to a small muscular segment or with lateral deviation and slight clonic jerks of the eyeballs. The state of consciousness is variable and often difficult to assess. Either initial complete loss of consciousness occurs, or consciousness is little, if at all, impaired and may fluctuate while the seizure develops. Most often, there is a loss of contact, and the clouding of consciousness increases with the duration of the seizure, as do the autonomic manifestations (hypersalivation, pallor, cyanosis, vomiting). The end of the seizure usually is sudden, immediately followed by a flaccid hemiplegia, with or without Babinski sign, in the side involved; this is of variable duration, depending in part on the duration of the seizure. This aspect is difficult to determine in a child in coma with unilateral SE. The side of the hemiplegia gives a good indication for the lateralization of the seizure, which is not always easy to define in small infants, particularly when the seizure is not directly observed by a doctor. Spontaneous postictal recovery is progressive with an agitation phase whereas, after seizure interruption by a drug injection, the child may sleep quietly. However, when the seizure has been protracted (>1 hour) there is a risk for a definitive hemiplegia, first flaccid then spastic; this sequence constitutes the hemiconvulsion-hemiplegia (HH) syndrome, usually followed by epilepsy and manifesting as hemiconvulsion-hemiplegia-epilepsy (HHE) syndrome.6 This syndrome has become rare with the advent of prompt, efficient treatment that shortens the duration of febrile seizures. The risk remains, however, for the development of later mesial TLE. It has been established by various authors that patients with mesial TLE often have had a long febrile seizure in early childhood.5 The exact type of this seizure is generally not indicated by the authors, but we think a high probability exists for HCS, because this seizure type is most prone to be of very long duration, and we have found it in the history of our own patients.

creating patterns of considerable complexity. At times they affect both sides of the body, either simultaneously as generalized seizures, or successively, as alternating epileptic seizures, so-called “see-saw epileptic seizures” or crises à bascule. They also can affect one upper limb and the opposite lower limb together, as crossed seizures. Another eventuality consists of a seizure reduced for some minutes to the loss of consciousness with only slight jerks localized to a small muscular segment or with lateral deviation and slight clonic jerks of the eyeballs. The state of consciousness is variable and often difficult to assess. Either initial complete loss of consciousness occurs, or consciousness is little, if at all, impaired and may fluctuate while the seizure develops. Most often, there is a loss of contact, and the clouding of consciousness increases with the duration of the seizure, as do the autonomic manifestations (hypersalivation, pallor, cyanosis, vomiting). The end of the seizure usually is sudden, immediately followed by a flaccid hemiplegia, with or without Babinski sign, in the side involved; this is of variable duration, depending in part on the duration of the seizure. This aspect is difficult to determine in a child in coma with unilateral SE. The side of the hemiplegia gives a good indication for the lateralization of the seizure, which is not always easy to define in small infants, particularly when the seizure is not directly observed by a doctor. Spontaneous postictal recovery is progressive with an agitation phase whereas, after seizure interruption by a drug injection, the child may sleep quietly. However, when the seizure has been protracted (>1 hour) there is a risk for a definitive hemiplegia, first flaccid then spastic; this sequence constitutes the hemiconvulsion-hemiplegia (HH) syndrome, usually followed by epilepsy and manifesting as hemiconvulsion-hemiplegia-epilepsy (HHE) syndrome.6 This syndrome has become rare with the advent of prompt, efficient treatment that shortens the duration of febrile seizures. The risk remains, however, for the development of later mesial TLE. It has been established by various authors that patients with mesial TLE often have had a long febrile seizure in early childhood.5 The exact type of this seizure is generally not indicated by the authors, but we think a high probability exists for HCS, because this seizure type is most prone to be of very long duration, and we have found it in the history of our own patients.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree