Chapter 18 Growth Hormone–Secreting Tumors

Phenotypic features of acromegaly include acral enlargement; coarse facial features with frontal bossing, prognathism, diastema and macroglossia; skin thickening, hypertrichosis, malodorous hyperhidrosis, and acanthosis nigricans; and deepening of the voice due to laryngeal hypertrophy. Other manifestations include headaches, lethargy, obstructive sleep apnea, peripheral neuropathies such as carpal tunnel syndrome, and bony deformation including bone thickening and vertebral osteophyte formation. Other consequences include abnormal carbohydrate metabolism and diabetes mellitus; cardiovascular diseases including hypertension, atherosclerosis, and cardiomyopathy; and an increased risk of other neoplasms including colon cancer.1–6 Patients with acromegaly have a two- to three-fold increase in mortality due to cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. Normalization of GH levels may decrease this risk substantially to levels comparable to the general population.7,8 Other clinical manifestations are related to mass effect of the pituitary tumor, including headaches, visual loss (classically bitemporal hemianopia), and hormonal deficiencies (hypogonadism, hypothyroidism, and hypoadrenalism).

The disease is insidious, which leads to a delayed diagnosis, often seven to ten years after onset of symptoms.9 Recently, this lag has shortened significantly, likely due to the increase in magnetic resonance imaging.10 Patients with acromegaly generally present in the third to fifth decade, and both sexes are affected equally.11

The average annual incidence of acromegaly is three to four per million, and the prevalence is 40 to 70 cases per million people.7,10 The vast majority of cases, 95% to 98%, are due to a GH-secreting pituitary adenoma.9,10,12 Pituitary adenomas from somatotroph cells may lead to excessive secretion of GH, while adenomas from acidophil stem cells or mammosomatotrophs often secrete both GH and prolactin (PRL).9,12 Most GH-secreting tumors (75%–80%) are macroadenomas (>1 cm in diameter),7 and 20% to 50% co-secrete PRL or other pituitary hormones.13 Rare causes of acromegaly include ectopic GH-secreting tumors such as bronchial carcinoid or pancreatic islet cell tumors; hypothalamic GH-releasing hormone (GHRH)-secreting tumors; exogenous administration of GH; or familial syndromes such as McCune-Albright syndrome, multiple endocrine neoplasia I (MEN-I) or Carney complex.9

Growth Hormone

There is some heterogeneity in GH due to differential splicing and post-translational modification.14–16 Two main forms of GH are found in the circulation: the 22K form comprises 90% of serum GH, and the 20K form makes up 5%.16 This heterogeneity may explain differences between levels measured by radioimmunoassays and actual biological activity in some patients.

Diagnosis

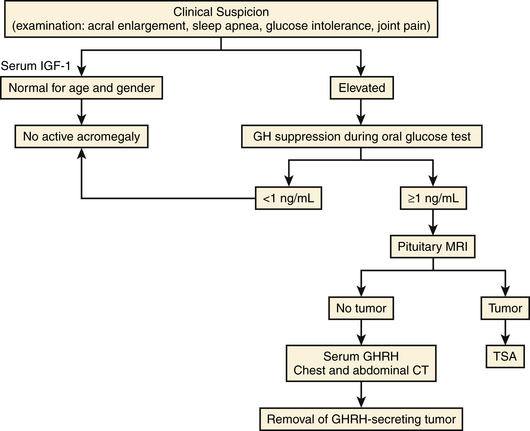

The suspicion of acromegaly is usually based on physical examination, while incidental radiologic detection in patients without typical manifestations is rare. Laboratory testing is needed to prove GH excess, while radiology techniques are used to visualize the tumor (Fig. 18-1). Screening laboratory tests include measurement of basal GH and IGF-1, and laboratory confirmation occurs when GH fails to suppress with oral glucose tolerance testing.

Laboratory Diagnosis

Random Serum GH Measurement

In healthy subjects, random GH levels are less than 5 ng/ml while most acromegalic patients have levels greater than 10 ng/ml. In active acromegaly, the normal episodic GH pattern is replaced by a constantly elevated GH level throughout the day.1 However, GH levels fluctuate widely and GH has a short half-life, so some acromegalic patients have normal GH levels on initial testing. Serum GH levels may be elevated in other conditions including uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, renal failure, malnutrition and during physical or emotional stress, even in the absence of acromegaly.13 Therefore, random GH measurement is not the preferred screening test for acromegaly.

IGF-1 Measurement

Serum IGF-1 measurement is the best single test for screening. The measurement of IGF-1 is used to provide an indicator of the body’s overall exposure to GH. Normal ranges for IGF-1 vary between different assays and are age- and gender-dependent.13 IGF-1 is increased in nearly all acromegalic patients, even those in whom random single GH levels are within the normal range. IGF-1 is also a reliable indicator for post-treatment hormonal remission, as it reflects GH secretion over the prior 24 hours.4 One of the IGF-1 binding proteins (IGFBPs) can be measured to assist in the diagnosis of acromegaly. The level of IGFBP-3 correlates directly with GH, but the overlap with normal persons limits its use.

GH Suppression to Hyperglycemia

The oral glucose suppression test (75 g) is used to confirm a diagnosis of acromegaly. In a normal control, GH decreases to below 1 ng/ml after a glucose load, whereas in an acromegalic patient, this suppression fails to occur.17 This test is useful to document biochemical remission after surgical removal of the pituitary tumor,18 but does not appear to be useful to assess control in patients receiving therapy with somatostatin analogues.17

Other Dynamic Tests

Other dynamic tests are rarely needed to diagnose acromegaly. Thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) stimulation leads to a significant increase in GH in untreated acromegalics, although it does not cause a significant change in GH levels in normal subjects. This response may also occur in the setting of liver disease, renal failure, or depression. TRH-stimulation may identify patients who, despite a normal postsurgical GH level, have residual GH-secreting tumor.19 Administration of oral L-Dopa or bromocriptine, a dopamine agonist, to a fasting normal subject increases GH secretion, though it paradoxically decreases GH levels in a fasting acromegalic patient.20

GHRH

GHRH levels should not be routinely used in diagnosis of acromegaly. However, they are useful in patients with confirmed acromegaly who do not harbor a pituitary tumor. Ectopic acromegaly, due to non-central nervous system tumors such as a pancreatic islet cell tumor or a bronchial carcinoid, results in a significantly elevated serum GHRH, whereas GHRH is usually low with a GH-secreting adenoma.21

Other Hormones

Hormonal assessments are needed to measure prolactin co-secretion, although moderately elevated prolactin can be due to stalk effect. Pituitary hormone deficiencies may be measured by ACTH, cortisol, TSH, free T4, FSH, LH levels in both genders, estradiol in women, and testosterone in men.

Treatment

Surgery

Surgical adenomectomy by an experienced neurosurgeon remains the first-line treatment for most patients with acromegaly.22,23 The goals of surgical resection are to eliminate mass effect, preserve or restore pituitary and visual function, and obtain tissue for histopathologic analysis.24

Most of these tumors are sellar or suprasellar lesions that may be removed trans-sphenoidally using a direct endonasal, sublabial, or trans-septal approach with an endoscope or microscope. The first trans-sphenoidal resection of a pituitary lesion was performed by Hermann Schloffer in 1907; the procedure was popularized by Harvey Cushing in the two decades that followed.25,26 Neurosurgeons have been improving the trans-sphenoidal adenomectomy (TSA) since. A craniotomy may rarely be necessary when a tumor has extensive suprasellar or parasellar extension.

Endoscopy

The lesion is removed in the same manner as described with the microscopic approach. Duraform is then placed over the sella, and the sphenoid sinus is packed using Gelfoam. NasoPore is laid over the posterior septectomy site and the sphenoethmoid recesses bilaterally. A mucosal septal flap may be used if a CSF leak is present. A speculum is not needed with this approach.27,28

The straight surgical endoscope provides a wide field of view, while angled scopes permit enhanced visualization of the sellar wall, suprasellar, retrosellar, or parasellar regions. Three-dimensional endoscopes have been recently introduced and provide a stereoscopic, nondistorted view of the regional anatomy in contrast to older two-dimensional endoscopes (Figure 18-2).

Sublabial Trans-Sphenoidal Approach

Sublabial may be the appropriate approach for patients with large tumors or pediatric patients with small nares. The upper lip is retracted, an incision is made horizontally in the gingival mucosa, and the maxilla and nasal cavity floor are accessed. A vertical incision is made to separate the nasal mucosa from the septum, and the anterior septum is subluxed and deviated. The speculum is inserted and the microscope or endoscope is brought into the field. The operation continues in the same manner as described above.29

Neuronavigation

Frameless stereotactic neuronavigation permits the surgeon to confirm his position at any point during the TSA to assess the proximity of surrounding structures or determine when he is approaching the limits of the tumor (Figure 18-3). Navigation may be used to assist with large lesions that involve the carotid arteries or recurrent lesions where the normal anatomy has been altered by a prior operation.30,31

Outcomes of Trans-Sphenoidal Surgery

Clinical Outcomes

Following operative decompression, visual field defects improve in 70% to 89% of patients,32,33 remain unchanged in 7% percent, and rarely worsen (<4%).34 Headaches usually improve in a few days, while soft-tissue swelling and glucose and blood pressure control improve progressively in the next few weeks postoperatively. Bony abnormalities persist, while joint symptoms often improve, although complete resolution is unlikely.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree