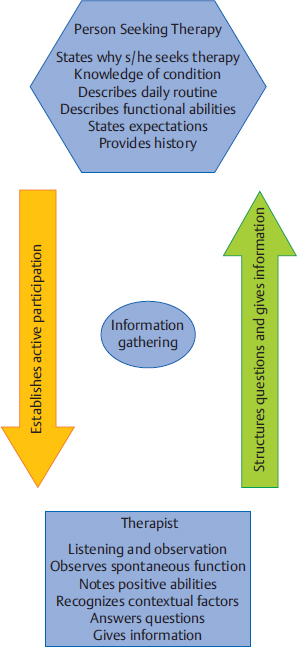

6 Information Gathering This chapter expands on the Neuro-Developmental Treatment (NDT) Practice Model’s Information Gathering section, describing the problem solving and actions involved in the relationship among all who are seeking intervention and other management of a client with a neurodisability. Learning Objectives Upon completing this chapter the reader will be able to do the following: • List at least five contributions of the client/family and the clinician to the process of information gathering. • Explain why information gathering is a critical portion of the NDT Practice Model. • Discuss why information gathering permeates the entire therapeutic process and why it occurs throughout all intervention sessions. • Explain why knowledge of pathology; lifelong change; motor development, motor control, motor learning, neuroplasticity; psychosocial functioning and human behavior; and participation, activity, and posture and movement are important during information gathering using the NDT Practice Model. Chapter 5 introduced the Information Gathering portion of the Neuro-Developmental Treatment (NDT) Practice Model (Fig. 6.1). The key feature of information gathering is the interaction between client/family and clinician. NDT views this communication as critical to establishing baseline information, just as the initial examination establishes baseline information. For the clinician using NDT, who the client and family are is just as important as what examination findings reveal. NDT does not limit its interest to medical information only; rather, it incorporates the biopsychosocial scope of the ICF model into its practice. NDT views the relationship with a client and family as one where the clinicians’ roles are to provide professional services within the client’s expressed goals, which clinicians document as intervention outcomes. The information provided by the client, family, and clinician is expressed in both verbal and nonverbal communication among all present and is received by the clinician in a nonjudgmental manner. NDT philosophy advocates building trust so that the client/family feels comfortable expressing their concerns, needs, and successes. The client and family are encouraged to express their understanding and perspectives about the purpose and results of intervention. The clinician is interested in whatever the family says and does not discourage expression of information or desired outcomes that seem unreasonable or unlikely in the clinician’s viewpoint. Clinicians are likely to spend considerable time with the client and family over weeks, months, and perhaps years, and the first consideration they desire is the family’s trust to freely express themselves. If families or clients express the desire to walk or walk again, talk or talk again, feed themselves or play soccer again, they may express this regardless of the likelihood of achievement of these outcomes. Our clients and their families are coping with the consequences of an often-times devastating disability. They express sadness, outrage, fear, and confusion. Their stories can be an emotional experience for the clinician, but listening is crucial for building trust. It is not possible for most people to cope with the consequences of disability without the support, repetition of information, hard work in intervention management, and individualized care that the situation demands. An 8-month-old baby newly diagnosed with spastic diplegic cerebral palsy visits a physical therapist who uses the NDT Practice Model. The baby and mother attend the initial session. Later, the therapist interacts with the baby’s father and several grandparents, including the paternal grandfather, who is the one bringing the child to most therapy sessions over several years’ time. The mother initially asks when the baby will catch up since his development is delayed (this description is her understanding of her baby). The therapist repeats information for months that gradually allows the mother to think about a different course of development for her child, rather than thinking he will catch up. The therapist is patient with repetitive questions and with the mother’s posing of ideas and scenarios for helping her son walk normally. The therapist realizes that this information is difficult for the mother to cope with. It is not that she doesn’t understand what the therapist is saying; it is that the information is too emotionally demanding to simply accept. The therapist encourages questions and suggests that the mother ask the same questions of other team members. When the child is a teenager receiving periodic episodes of care, the mother reflects about her early experience to the therapist one day. She tells the therapist that she still has a difficult time some days coming to terms with the differences in her son’s physical abilities, although she is very proud of how well he excels socially and academically. She further notes that she varies in her ability to accept her son’s cerebral palsy, and she guesses she will always be that way. When her son encounters new difficulties, as he did when figuring out how to negotiate a college campus, her own fears increase and a certain level of sadness overtakes her. The therapist listens, reflecting on the meaning of cerebral palsy to the teen and his mother over their lifetimes so far. The therapist deepens her own understanding of the meaning of a lifelong disability for this family. Information sharing is therefore crucial to the growth and understanding of each person involved with this teen and how it affects all of their lives. By establishing a system of communication, NDT values active participation of the client and family in all aspects of care. The client and family are encouraged to take the lead by providing information that they know more about than anyone else does. This initially takes the form of providing information about the client’s unique personal attributes and abilities, likes and dislikes, and relationships to key people in his or her life. This contextual information is critical in assisting the client and family to establish and measure profession-specific outcomes for therapeutic intervention. Mr. Hayden had a stroke due to right middle cerebral arterial ischemia with resultant left hemiparesis and spatial neglect. He is concerned about his role as the family financial provider. Although close to retirement, he says that he wants to work for a few more years. His wife states that the family is able to manage if he cannot return to work, but Mr. Hayden’s goals for physical and occupational therapy are all focused on the physical skills he thinks will allow him to return to work. Mrs. Hayden provides details about how her husband is faring within the home environment, which helps his therapists gauge how functional he is becoming in that setting.

6.1 Information Gathering Using the NDT Practice Model

6.1.1 Building Trust

Example

6.1.2 Establishing Communication

Example

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree