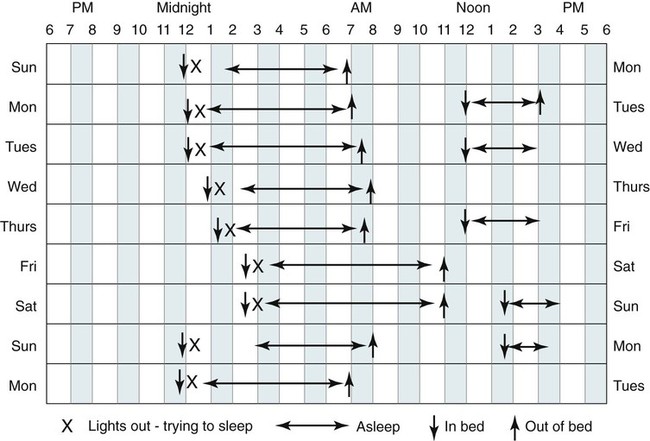

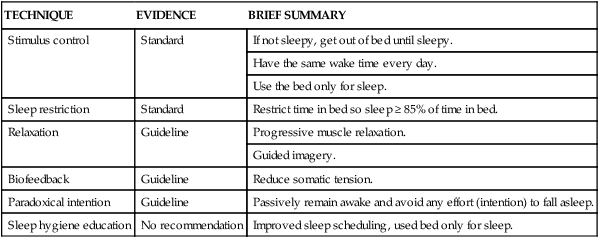

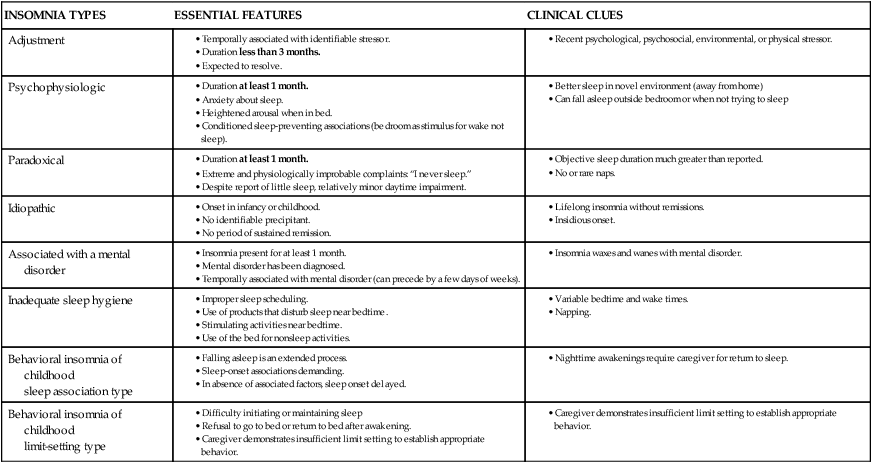

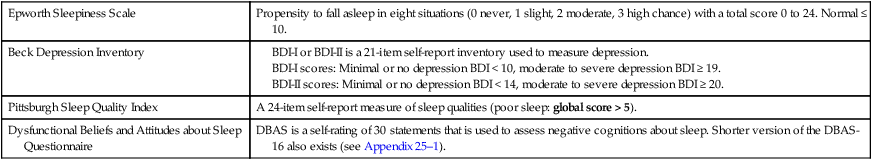

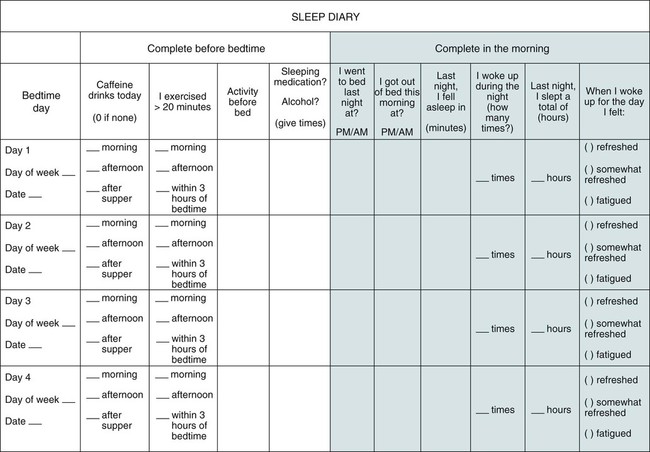

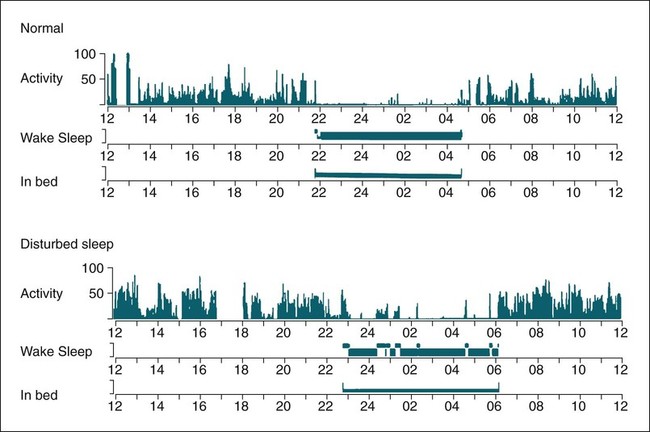

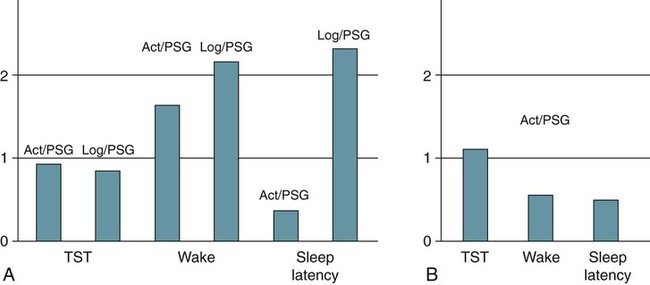

• A diagnosis of insomnia requires some type of daytime impairment related to nocturnal sleep difficulty. • Adjustment insomnia is characterized by insomnia with a duration less than 3 months that is temporally associated with an identifiable stressor and expected to resolve. • Psychophysiologic insomnia must have a duration of at least 1 month and is characterized by conditioned sleep-preventing associations—the bedroom is a stimulus for wake not sleep. Patients can often fall asleep better in a novel setting or at home outside the bedroom. • Idiopathic insomnia is present since infancy or childhood, has no identifiable precipitant (insidious onset), and no period of sustained remission. • Paradoxical insomnia is characterized by a duration of at least 1 month and complaints of little or no sleep but relatively minor daytime consequences and no or rare naps. The degree of sleep reduction reported far exceeds that noted with objective determinations of sleep (PSG) or estimates of sleep (actigraphy). • Inadequate sleep hygiene is characterized by a duration of at least 1 month and improper sleep scheduling, stimulating activities near bedtime, or use of the bed for nonsleep activities. • Insomnia Due to Drug or Substance is characterized by a duration of at least 1 month and ongoing dependence and abuse of sleep-disruptive medication or substance with symptoms either during intoxication or withdrawal OR current exposure to medication or substance known to disturb sleep in susceptible individuals. The complaint should be temporally associated with use or withdrawal of the medication or substance. • Insomnia Due to Mental Disorder is characterized by insomnia of a duration of at least 1 month that is temporally associated with (or slightly preceding) the onset of the mental disorder, waxes and wanes with the severity of the mental disorder, and is more prominent than expected for the disorder such that the insomnia is causing marked distress or is an independent focus of treatment. • Behavioral Insomnia of Childhood is divided into sleep-association type (requires certain conditions for sleep onset) and limit-setting type (refusal to go to sleep). • The most common cause of insomnia is the presence of a psychiatric disorder. • The most important characteristic of a BZRA to consider when choosing a medication to treat insomnia is the duration of action. • Hypnotics with a short duration of action are indicated to treat sleep-onset insomnia (e.g., zaleplon, ramelteon). • BZRAs with intermediate duration of action are indicated to treat sleep-onset or sleep-maintenance insomnia (zolpidem CR, eszopiclone, temazepam). Zolpidem is also effective for sleep-maintenance insomnia in some patients. • CBT of insomnia (also known as CBTI) is effective for both primary and secondary (co-morbid) insomnia including insomnia due to medical conditions. The combination of a hypnotic and CBTI is NOT more effective than CBTI alone for primary insomnia. • CBTI is defined as cognitive therapy + stimulus control and/or sleep restriction with or without relaxation therapy. • Major behavioral techniques with their level of evidence are shown in the following table. • Options for treatment of insomnia in a patient with depression include using (1) a sedating antidepressant at a dose effective for depression, (2) an effective antidepressant + a low dose of a sedating antidepressant, (3) an effective antidepressant + a BZRA. In patients with a history of alcohol or drug dependence, use of a BZRA should be avoided. • In patients with benign prostatic hypertrophy, medications with anticholinergic side effects should be avoided. The International Classification of Sleep Disorders, second edition (ICSD-2)1 lists diagnostic criteria for insomnia (Box 25–1) that include requirements for an insomnia sleep complaint, adequate opportunity/sleep, and some form of daytime impairment related to the sleep difficulty. The sleep complaints associated with insomnia include difficulty initiating sleep (sleep-onset insomnia), difficulty maintaining sleep (sleep-maintenance insomnia), waking up too early, or sleep that is chronically nonrestorative or poor in quality. A diagnosis of insomnia requires that patients must report at least one of these insomnia complaints. However, it is not uncommon for individual patients to report all of them. There must be adequate opportunity and circumstances for sleep to occur. A diagnosis of insomnia also requires evidence of daytime impairment related to the sleep problem. Patients suffering from insomnia may report a wide variety of complaints (see Box 25–1) including fatigue or malaise, problems with attention or concentration, memory impairment, social or vocational dysfunction, and poor school performance. Other symptoms associated with insomnia include mood disturbance or irritability; daytime sleepiness; reduction in motivation or initiative; proneness to error/accidents at work or while driving; tension headaches or gastrointestinal symptoms in response to sleep loss; and concerns or worries about sleep.1 In children, the sleep difficulty is often reported by the caretaker and may consist of observed bedtime resistance or inability to sleep independently. Although the minimum duration of insomnia complaints is not specified in the definition of insomnia (see Box 25–1), the diagnostic criteria for several individual insomnia types does specify a minimum duration of 1 month.1 It has been estimated that insomnia complaints occur on at least a few nights per year in 33% to 50% of the adult population. Insomnia complaints plus symptoms of impairment due to insomnia occur in 10% to 15% of the population. Specific insomnia disorders occur in 5% to 10%.2–5 A number of risk factors for the development of insomnia have been identified, including older age, female gender, co-morbid problems (depression and other psychiatric disorders, substance abuse), shift work, unemployment, and lower socioeconomic status. Some studies suggest that single, divorced, and separated patients have greater insomnia rates than married patients. The most common cause of insomnia in patients evaluated by a physician is insomnia due to or associated with depression. Insomnia occurs in the majority of patients (80%) with major depressive or chronic pain disorders. Persistent insomnia symptoms increase the likelihood of developing a major depression within a 1-year period by a factor of four.3 In addition, up to one third of all cases of insomnia are associated with a mental disorder. The ICSD-2 classification lists a number of distinct sleep disorders associated with insomnia (Box 25–2). The three most common insomnia disorders include adjustment insomnia, psychophysiologic insomnia, and insomnia due to a mental disorder. A number of other sleep disorders not included in this group can also present with complaints of insomnia (see Box 25–2). The sleep apnea syndromes can be associated with repetitive arousal and sleep-maintenance problems. In patients with sleep apnea, insomnia symptoms are more likely to be present in women than in men.1 The circadian rhythm sleep disorders (CRSDs) can also be associated with insomnia complaints including the delayed sleep phase syndrome (sleep-onset insomnia) and the advanced sleep phase syndrome (early morning awakening). In the delayed sleep phase type, once the affected individuals are able to fall asleep, they have fairly normal sleep. In the advanced sleep phase syndrome, individuals fall asleep early but then awaken in the early morning hours. In CRSD free-running type, patients may report periods of insomnia alternating with hypersomnia.1 The restless legs syndrome/periodic limb movement disorder can also be associated with symptoms of insomnia or nonrestorative sleep. Other classifications of insomnia divide disorders into primary and secondary (co-morbid) insomnia. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV), lists diagnostic criteria for primary insomnia (307.42) (Box 25–3).6 This type of insomnia would include adjustment insomnia, psychophysiologic insomnia, paradoxical insomnia, idiopathic insomnia, and inadequate sleep hygiene. Insomnia associated with a mental disorder is termed secondary or co-morbid insomnia. The subtypes of insomnia listed in the ICSD-2 classification are each discussed in some detail. However, it is helpful to remember the major characteristics of each type (Table 25–1) when evaluating patients. TABLE 25–1 Major Characteristics of Insomnia Types in International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 2nd Edition Adapted from Schutte-Rodin S, Broch L, Buysee D, et al: Clinical guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic insomnia in adults. J Clin Sleep Med 2008;4:487–504. Clinical guidelines for the evaluation and management of chronic insomnia in adults have been recently published.7 This guideline document provides a succinct discussion that is a valuable resource for the clinician. Other, more extensive reviews of evaluation of insomnia and practice parameters for evaluation have also been published.5,8–10 A detailed sleep history is the cornerstone of evaluation of insomnia (Box 25–4). First, the nature of the primary sleep complaint (problems with sleep onset, sleep maintenance, or quality) should be defined and the duration of the complaint determined. The history of the origin of the complaint including age of onset should be explored and particular life events or stressors at the start of the problem should be identified. For example, patients with idiopathic insomnia report problems since childhood or adolescence with an insidious onset. Patients with psychophysiologic insomnia may report that chronic insomnia began after a severe illness. Presleep conditions or activities that could affect sleep including the bedroom environment, activities near bedtime, or mental state near bedtime should be explored. The bedroom environment should be characterized for factors that might disturb sleep (noise, clock easily seen from the bed, extreme hot or cold temperature). Activities near bedtime, including working late on the computer, drinking caffeinated beverages or alcohol in the evening, or exercise near bedtime, may impair the ability to sleep. The mental status at bedtime should be explored. Often, patients began worrying about their stresses and problems when retiring for the night. The presence or absence of nocturnal symptoms including snoring, gasping during sleep, symptoms of the restless legs syndrome, and body movements should be evaluated. The sleep-wake schedule should be determined by report including variability of bedtime and rise time as well as the frequency and duration of naps. Factors that worsen or improve sleep should be detailed. For example, some patients with psychophysiologic insomnia report sleeping better in a novel environment (reverse first-night effect).11 Patient recall can be supplemented by sleep logs and/or actigraphy as discussed in a following section. Daytime function should be discussed with emphasis on possible consequences of insomnia. Reports of daytime fatigue or impaired cognition and mood are more common than true daytime sleepiness. True daytime sleepiness should trigger suspicion for additional sleep problems such as sleep apnea, narcolepsy, or depression. Daytime activities that may affect sleep such as the amount of caffeine, alcohol, exercise, sunlight exposure, and napping should be detailed. A general medical and psychiatric history is important to identify mental or medical conditions that may affect sleep. A detailed medication history including over-the-counter medications and substances of abuse is extremely important. A physical examination and a general medical history including appropriate laboratory (if not recently performed) should rule out obvious medical causes of insomnia. Examination of the upper airway showing a high Mallampati score (upper airway narrowing)12 might trigger suspicions of obstructive sleep apnea. Supporting information from questionnaires (mood, cognition about insomnia), sleep logs, and actigraphy may be helpful in evaluating patients with insomnia (Table 25–2). These may supplement other information obtained from the sleep history. Assessing the patient’s attitudes about sleep and the sleep problem is as important as documenting the degree of sleep disturbance. In addition, some patients are hesitant to admit to feelings of depression. Sleep logs and actigraphy provide a more accurate estimate of the patient’s sleep quantity than is possible from patient recall. TABLE 25–2 Questionnaires to Evaluate Patients with Insomnia BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; DBAS = Dysfunctional Beliefs and Attitudes about Sleep. A number of questionnaires have been used to evaluate patients with insomnia. The Epworth Sleepiness Scale, as discussed in Chapter 12, is used to assess subjective estimates of propensity to fall asleep in common situations.13 The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) is a 24-item self-report measure of general sleep quality that specifically addresses the preceding 1-month period. The PSQI evaluates seven domains: duration of sleep, sleep disturbance, sleep-onset latency, daytime dysfunction due to sleepiness, sleep efficiency, need for medications to sleep, and overall sleep quality. The PSQI yields a global score and seven component scores (poor sleep: global score > 5).14,15 The questionnaire has been shown to discriminate healthy patients, patients with depression, and patients with sleep disorders. It was not designed specifically for insomnia but has been used in insomnia assessment and treatment studies. Detailed instructions for use and scoring of the PSQI are available at the University of Pittsburgh Sleep Medicine Institute website: http://www.sleep.pitt.edu/content.asp?id=1484&subid=2316 The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-I or BDI-II) is a 21-item self-report inventory used to measure manifestations of depression, each item being scored from 0 to 3.16,17 Higher total scores indicate more severe depressive symptoms. The BDI-II is a revision of the original BDI. The score ranges for the BDI-I are 0 to 9: minimal or no depression; 10 to 18: mild to moderate depression; 19 to 29: moderate depression; and 30 to 63: severe depression. The score ranges for BDI-II are 0 to 13: minimal or no depression; 14 to 19: mild depression; 20 to 28: moderate depression; and 29 to 63: severe depression. Because primary insomnia and major depression share some daytime symptoms, the usual cutoff scores for the BDI might be less specific for depression in insomnia patients.18 Indeed, one study evaluating the BDI-II in insomnia patients found that using a cutoff for mild depression of greater than 14 had a high sensitivity (91%) but low specificity (66%) for detecting depression. The authors suggested using a higher cutoff (>17) for mild depression. Using this cutoff the BDI-II had a 79% specificity but an 81% sensitivity for identifying depression. The Dysfunctional Beliefs and Attitudes about Sleep (DBAS) Questionnaire is a self-rating survey to assess negative cognitions about sleep.19,20 Reversal of these cognitions is a goal of the cognitive component of CBT (cognitive behavioral therapy). The original DBAS was a 30-item questionnaire in which patients responded using an analog scale (0, strongly disagree; 1, 2, 3. . ., to 10, strongly agree). A shorter version (DBAS-16)20 has recently been validated and is less time-consuming for patients to complete (Appendix 25–1). Having insomnia patients complete a sleep log (sleep diary) for at least 2 weeks is recommended. Sleep logs are often more accurate than relying on patient recall of their chronic sleep patterns. Sleep logs usually follow a question format (Fig. 25–1) or time plot graphic format (Fig. 25–2). The essential elements include the ability to assess time in bed (TIB), sleep-onset latency (SOL), total sleep time (TST), and the amount of wake after sleep onset (WASO). The TIB is the time period from when the patient gets in bed until the final time the patient leaves the bed in the morning. The WASO includes all wake from sleep onset until the patient leaves the bed in the morning. The patient need report only three of these four parameters because they are related (TIB = SOL + TST + WASO). One can compute a sleep efficiency (= TST × 100/TIB) with normal values exceeding 85%. Sleep logs also typically provide space to record caffeine consumption, bedtime activities, or medications taken for sleep as well as estimates of sleep quality. Sleep logs are very helpful in revealing general patterns of the sleep-wake cycle such as irregular bedtimes and wake times and the amount and frequency of napping. A few characteristic patterns noted in sleep logs are listed in Table 25–3. TABLE 25–3 Some Typical Sleep Log Patterns Actigraphy involves use of a portable device (often resembling a watch and typically worn on the wrist) that collects movement information (activity) over an extended period of time (Fig. 25–3). The absence of movement is assumed to be a surrogate of sleep.21–29 The use of actigraphy is included in the ICSD-2 diagnostic criteria for several CRSDs, paradoxical insomnia, and behaviorally induced insufficient sleep syndrome.1 Practice parameters for use of actigraphy have been published by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM).23,29 Some of the recommendations are listed in Box 25–5. Note that, although actigraphy was said to be indicated for determining the circadian patterns of patients with insomnia, the practice parameters did not state that actigraphy was indicated as a routine evaluation of patients with insomnia. Sleep logs and actigraphy provide complementary information. In a study of patients with insomnia undergoing treatment, Vallières and Morin24 compared findings from actigraphy and sleep logs with PSG (Fig. 25–4A). Both actigraphy and sleep logs underestimated TST and overestimated wake time. Actigraphy underestimated the sleep latency and sleep logs overestimated the sleep latency. These authors found actigraphy to be more sensitive at detecting treatment effects than sleep logs. In contrast, Sivertsen and coworkers25 found different results in a group of older adults treated for primary insomnia (expected to have more wake time). Actigraphy slightly overestimated TST and underestimated wake (see Fig. 25–4B). In this study, actigraphy provided a better estimate of TST than of wake time. PSG is not indicated for the routine assessment of insomnia.9,10 However, if there is a suspicion for sleep apnea, periodic limb movement disorder, or a parasomnia, a PSG may be useful. The 2003 AASM practice parameters for the role of PSG in insomnia stated “polysomnography is indicated when the initial diagnosis (insomnia) is uncertain, treatment fails (either behavioral or pharmacologic), or precipitous arousals occur with violent or injurious behavior (Guideline).”10 When PSG is performed, typical findings (Box 25–6) in patients with insomnia include a long sleep latency (>30 min), reduced TST, increased WASO, and a reduced sleep efficiency. A long rapid eye movement (REM) latency, high arousal index, increased stage N1, and decreased stage N3 sleep may also be noted. In patients with paradoxical insomnia, the objective sleep abnormality is much less severe than reported. It is not unusual for such patients to report little or no sleep following a PSG documenting only mild to moderate decrements in the TST. In some patients with psychophysiologic insomnia, the “reverse first-night effect”11 may be noted. In these patients, the sleep quality in the sleep center is better than that reported at home. It is essential to have all patients complete questionnaires assessing subjective sleep (estimate TST, sleep latency, sleep quality) after PSG. Some but not all studies have documented increased high-frequency EEG activity, increased whole body and brain metabolic activity, elevated heart rate, and sympathetic nervous system activation (decreased heart rate variability) during both day and night in patients with insomnia. These findings suggest that patients with insomnia are in a state of hyperarousal.30 Of special interest, functional neuroimaging has found greater global cerebral glucose metabolism during sleep and while awake and a smaller decline in relative metabolism from waking to sleep in wake-promoting regions in patients with insomnia compared with normal controls.31 In addition, reduced metabolism was found in the prefrontal cortex of patients with primary insomnia while awake. It is not clear whether these findings represent cause or effect. A recent study of magnetic resonance spectroscopy found a global reduction in gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in nonmedicated patients with primary insomnia compared with normal controls.32 This neurotransmitter is generally inhibitory and higher levels would be expected to promote sleep. Conditioned sleep difficulty, heightened arousal in bed, and learned sleep-preventing associations are the essential characteristics of this disorder. Mental arousal (“racing mind/thoughts”) occurring when trying to go to sleep is a common complaint. The patient becomes conditioned so that the bedroom is a “cue” to develop tension, anxiety, and inability to fall asleep. Some patients sleep better away from home. Patients typically can fall asleep during monotonous activities but not after getting into bed and trying to sleep. For example, a patient may fall asleep while watching television in the living room but become wide awake after entering the bedroom and attempting to sleep. This disorder may start after a precipitating event (death in family, job stress) but then persists owing to perpetuating behaviors even after the precipitating event has resolved. Other patients report a slow onset of symptoms. Patients may report a lifelong pattern of being “light sleepers” or episodically poor sleep (Box 25–8). Patients often report little or no sleep on many nights followed by days with relatively minimal dysfunction and no napping. In addition, patients with paradoxical insomnia often report hearing every noise in the house while in the bedroom and/or actively thinking for the entire night. Daytime impairment reported is consistent with other types of insomnia but is much less severe than expected, given the severe level of sleep deprivation reported. For example, there are no intrusive sleep episodes or serious mishaps due to loss of alertness, even following nights reportedly without sleep (Box 25–9). Idiopathic insomnia is also called childhood-onset insomnia. The patient usually recalls the insidious onset of the insomnia problems in childhood. The history is one of lifelong insomnia problems (Box 25–10). Idiopathic insomnia occurs in less than 10% of patients with insomnia. Idiopathic insomnia is a rare disorder occurring in only approximately 0.7% of adolescents.1

Insomnia

TECHNIQUE

EVIDENCE

BRIEF SUMMARY

Stimulus control

Standard

If not sleepy, get out of bed until sleepy.

Have the same wake time every day.

Use the bed only for sleep.

Sleep restriction

Standard

Restrict time in bed so sleep ≥ 85% of time in bed.

Relaxation

Guideline

Progressive muscle relaxation.

Guided imagery.

Biofeedback

Guideline

Reduce somatic tension.

Paradoxical intention

Guideline

Passively remain awake and avoid any effort (intention) to fall asleep.

Sleep hygiene education

No recommendation

Improved sleep scheduling, used bed only for sleep.

Prevalence of Insomnia and Risk Factors

Insomnia Subtypes

INSOMNIA TYPES

ESSENTIAL FEATURES

CLINICAL CLUES

Adjustment

Psychophysiologic

Paradoxical

Idiopathic

Associated with a mental disorder

Inadequate sleep hygiene

Behavioral insomnia of childhood

sleep association type

Behavioral insomnia of childhood

limit-setting type

Evaluation of Insomnia Complaints

Questionnaires, Sleep Logs, and Actigraphy

Epworth Sleepiness Scale

Propensity to fall asleep in eight situations (0 never, 1 slight, 2 moderate, 3 high chance) with a total score 0 to 24. Normal ≤ 10.

Beck Depression Inventory

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

A 24-item self-report measure of sleep qualities (poor sleep: global score > 5).

Dysfunctional Beliefs and Attitudes about Sleep Questionnaire

DBAS is a self-rating of 30 statements that is used to assess negative cognitions about sleep. Shorter version of the DBAS-16 also exists (see Appendix 25–1).

Questionnaires

Sleep Logs

Delayed sleep phase

Late bedtime or long sleep latency, few awakenings, normal sleep duration on weekends or nonwork/nonschool days.

Inadequate sleep hygiene

Irregular wake and rise times, naps.

Psychophysiologic insomnia

Long sleep latency, decreased total sleep time, frequent awakenings.

Variability in sleep quality.

Paradoxical insomnia

Nights of minimal or no sleep are reported followed by no or few naps the next day.

Actigraphy

Polysomnography

Physiologic Findings in Primary Insomnia

Individual Insomnia Subtypes

Adjustment Insomnia (Acute Insomnia)

Psychophysiologic Insomnia

Key Features

Paradoxical Insomnia (Sleep State Misperception)

Key Features

Idiopathic Insomnia

Epidemiology

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Insomnia