Metastases

Meningioma

Pituitary adenoma

20-30%

20-30%

10-15%

Lymphoma

Acoustic neuroma

Pinealoma

Colloid cyst

1%

<1%

<1%

<1%

CLINICAL FEATURES

Intracranial tumours in Africa are characterised by late presentation with on average a 2 year delay before diagnosis and a high mortality of >80% at 1-2 years follow up. They can exist for long periods with no or few symptoms and when symptoms do occur the tumours may be advanced. Headache is the most common complaint though occurring only in <50% of cases. Pain is variable, ranging from being dull, low grade and intermittent to being severe, continuous, deep, nocturnal, present on waking and often associated with vomiting. Intracranial tumours have three recognizable main modes of clinical presentation (Table 16.2): (1) focal neurological deficits (FND), (2) seizures, and (3) raised intracranial pressure (↑ICP). These can occur either alone or together depending on type, stage and site of tumour. The pathogenic mechanisms underlying these presentations include tumour mass effect, brain irritation and blocked CSF flow. Highly malignant or fast growing tumours tend to present with combinations of all three main modes of presentation occurring over weeks or months whereas low grade or slow growing tumours tend to present with isolated seizures and/or neurological deficits occurring over months or years. The age of the patient, speed of onset of symptoms and neurological findings all help to determine the site and the probable type of tumour.

Table 16.2 Main presenting clinical features of intracranial tumours

| Neurological finding | Symptoms/Signs |

| focal neurological deficits | hemiparesis, dysphasia, visual loss, field defect, ataxia, cranial nerve palsies |

| raised intracranial pressure | headaches vomiting, papilloedema, LOC |

| seizures | simple or complex partial, secondary GTC |

Focal neurological deficits

FND are the most common neurological presentation of brain tumour. The type of FND is very variable and reflects the cell type, grade of malignancy and the site affected (Chapter 2). These include hemiparesis, dysphasia, visual loss, field defects, cognitive impairment, personality change, cranial nerve palsies and ataxia. The combination of ataxia and cranial nerve palsies occurs more frequently with tumours arising in the posterior fossa.

Seizures

Seizures are the presenting complaint in approximately a quarter of patients and occur as a complication in about another quarter (Chapter 4). Seizures arise mostly from tumours affecting the temporal lobes and occur most commonly in association with malignant tumours. The seizures are mostly generalised tonic clonic-type seizures with a focal origin.

Raised intracranial pressure (↑ICP)

The symptoms and signs of ↑ICP are headache, vomiting, papilloedema and altered level of consciousness; these occur because of either mass effect or hydrocephalus. Hydrocephalus arises because of mechanical blockage to CSF flow through the ventricles. Headache is the most common symptom being typically severe in advanced tumours, often waking the person from sleep during the night or early morning and frequently associated with vomiting (Chapter 15). The site of the headache is mostly frontal in supratentorial tumours and occipital in posterior fossa tumours, however the site may not necessarily be localising. Mass lesions arising from above the tentorium, and affecting both the hemispheres frequently give rise to combinations of features of FNDs and ↑ICP. The most common neurological deficits include hemiparesis and 3rd, 4th and 6th nerve palsies. These may be false localising signs, if they occur as a result of remote compression at a site away from the tumour. Space occupying lesions (SOL) arising below the tentorium within the posterior fossa cause cranial nerve palsies, ataxia, and long track signs and raised ICP secondary to obstructive hydrocephalus. A history of visual disturbances and the presence of papilloedema are usually late clinical findings. Eventually, the expanding tumour results in herniation either through the tentorium or foramen magnum leading to death.

Key points

- most common malignant ICTs are gliomas & metastases

- most common benign ICTs are meningiomas & pituitary adenomas

- main presentations include progressive FNDs, seizures & ↑ICP

- other presentations are headaches, visual failure, cranial nerve signs & seizures

- most patients presenting with headaches do not have brain tumours

MAIN SITES

The site and types of intracranial tumour determine the presenting symptoms and signs and the main ones are outlined below (Chapter 2).

Frontal lobe

Tumours involving the frontal lobe typically present late because the frontal lobe has a large silent area. Contralateral hemiparesis occurs if the motor strip is involved. Tumours involving the anterior frontal lobe may present with personality changes and a loss of initiative, inhibition and cognitive function. There may also be focal motor seizures, urinary incontinence and loss of smell. An expressive aphasia occurs if Broca’s area in the dominant hemisphere is involved.

Parietal lobe

Tumours of the parietal lobe result in difficulties or inability to recognise sensory and proprioceptive input from the opposite side of the body. This may show itself as tending to ignore the contralateral side visuospatially (hemineglect) or as difficulties recognizing familiar shapes, textures or numbers when placed in the opposite hand (astereognosia). If the dominant hemisphere is involved, there may be difficulties particularly with understanding speech, numbers, reading and writing and carrying out motor tasks (apraxia). Patients with non dominant hemisphere involvement may present with or develop hemineglect. Patients may also have a visual field defect involving the lower quadrant from the opposite side.

Temporal lobe

Tumours involving the dominant temporal lobe (usually left sided) may result in aphasia which is receptive in type and also memory impairment. Tumours on either side may result in recent onset temporal lobe seizures and visual field loss in the contralateral upper quadrant.

Occipital lobe

Tumours involving the occipital lobe present with visual disturbances, hallucinations, and a loss of vision from the opposite side of the body, a contralateral homonymous hemianopia.

Brain stem and cerebellum

Tumours of the brain stem present with a combination of ipsilateral cranial nerve palsies and cerebellar ataxia, and contralateral long tract signs. These may be associated with hydrocephalus and ↑ICP depending on the tumour type and site. Tumours involving this area of the brain are more common in children.

GLIOMA

Gliomas account for up to half of all brain tumours and occur most commonly in older age groups >50-60 years. Glioma is the generic name for brain tumours of neuroepithelial cell origin. These are the support cells in the brain and the main ones are astrocytes and oligodendrocytes. Astrocytic tumours are separated histologically into grades I & II which are low grade, well differentiated and relatively benign and into grades III & IV which are high grade, poorly differentiated and highly malignant. Glioblastoma multiforme represents the most malignant stage of glioma. Oligodendrogliomas on the whole tend to be lower grade tumours characterized by a capsule and the presence of cysts and calcium with a good prognosis, but after years about one third may evolve into more malignant tumours.

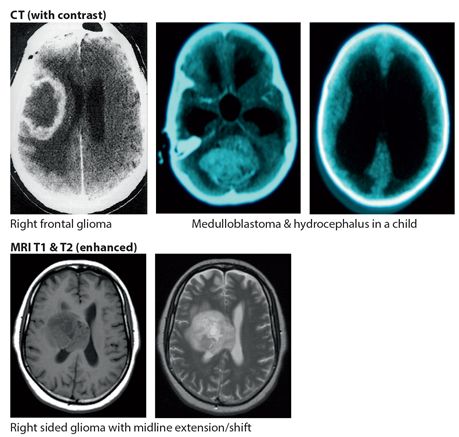

Other forms of glioma include ependymomas which are derived from cells which line the ventricles and choroid plexus. Medulloblastomas are gliomas of the cerebellum and the roof of the 4th ventricle occurring mostly in young children aged 4-8 years (Fig. 16.1).

Figure 16.1 Gliomas

Clinical features

Gliomas present clinically with increasing symptoms usually over weeks or months or years depending on the grade of malignancy. Presentations include headache and combinations of focal neurological deficit, seizures, and signs of ↑ICP. Diagnosis is confirmed by neuroimaging, most commonly a CT of the head. It typically shows a unifocal enhancing mass with surrounding oedema and mass effect (Fig. 16.1).

Management

Management where there are full resources includes a combination of surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Surgery is indicated for biopsy to establish a tissue diagnosis and for partial tumour resection to relieve symptoms. Chemotherapy is used in high grade malignant gliomas and usually involves the alkylating drug temozolomide in combination with other drugs. However temozolomide is expensive, used mostly but not exclusively in younger patients and only available in some specialized oncology units. Radiation is indicated for most high grade gliomas but this is only palliative at this stage.

Prognosis

The prognosis in low grade gliomas is good with a median survival of 8-10 years. However in patients with higher grade malignancy the prognosis even with treatment is poor with survival of usually <12 months.

Key points

- gliomas account for almost half of all ICTs

- presentations include ↑ICP, FNDs & seizures over weeks & months

- diagnosis is by neuroimaging, CT or MRI

- management is mainly with combination of surgery, chemotherapy & radiotherapy

- prognosis for high grade gliomas is poor

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree