Intradural Intramedullary and Extramedullary Tumors

Ryan M. Kretzer

George I. Jallo

CASE ILLUSTRATIONS

CASE 1—INTRADURAL INTRAMEDULLARY SPINAL CORD TUMOR

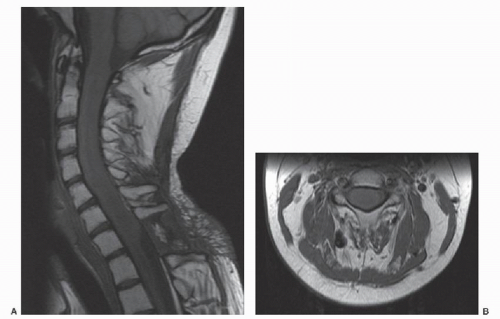

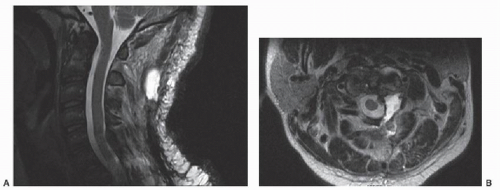

An otherwise healthy 17-year-old male presented to his primary care physician with progressive neck and back pain. His past medical history and family history were unremarkable. Subsequent workup, including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the cervical and thoracic spine, was notable for an intramedullary spinal cord tumor (IMSCT) extending from C1- to C7 (Fig. 54.1A and B). The patient was started on decadron and underwent biopsy of the lesion at the C7-T1 level at another institution. Pathology was consistent with an ependymoma, and the patient was subsequently treated with a 28-day course of radiation therapy. Over the ensuing months, the patient’s pain significantly worsened, severely limiting his daily activities. He also developed paresthesias in his bilateral upper and lower extremities and weakness in his hands. He was referred to our institution for a second opinion and further care.

On physical examination, the patient demonstrated physical stigmata of chronic steroid therapy and had limited range of motion in his neck secondary to pain. Strength in his upper and lower extremities was 4/5 in all muscle groups, and sensation was grossly intact to light touch throughout. His deep tendon reflexes were 2+ in the upper extremities and 3+ in the lower extremities, and his toes were downgoing bilaterally. He demonstrated a slow and shuffling gait.

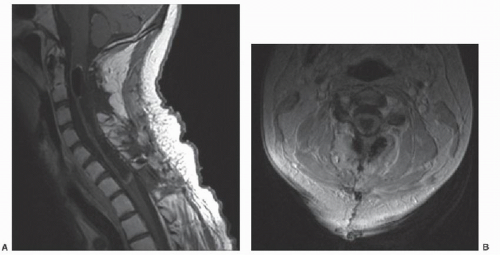

After extensive discussion with the patient and his family regarding the risks and benefits of surgery, the patient was taken to the operating room for a C2-C7 osteoplastic laminotomy and gross total resection of the cervical ependymoma. The dura was closed primarily without use of a dural substitute. Closure of the wound was performed with the assistance of plastic surgery using bilateral paraspinous muscle flaps secondary to the patient’s previous surgical incision and radiation exposure. All neurophysiologic monitoring remained unchanged at the end of the case. Postoperatively, the patient’s strength remained at his neurologic baseline, and a cervical spine MRI performed 2 days after surgery showed excellent resection of the intramedullary lesion (Fig. 54.2A and B).

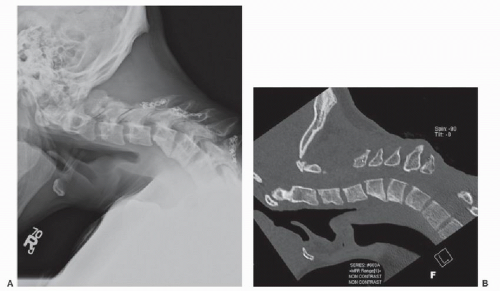

The patient’s postoperative course was complicated by CSF leak from his drain site, which was treated conservatively with superficial oversewing. Approximately 1 year after surgery, the patient also developed progressive cervical kyphosis (Fig. 54.3A and B).

CASE 2—INTRADURAL EXTRAMEDULLARY SPINAL CORD TUMOR

A 14-year-old male initially presented to the emergency room with a 2-week history of progressive left lower extremity weakness and numbness. Workup was significant for two compressive intradural extramedullary lesions in the cervicothoracic and upper thoracic region, which were subsequently removed via osteoplastic laminotomy from C7 to T2. Pathology was consistent with multiple meningiomas. At the time of initial presentation, a left-sided extra-axial mass at the level of C1-C2 adjacent to, but not compressing, the spinal cord was also found. He was diagnosed with

neurofibromatosis type 2 secondary to multiple intracranial and intraspinal tumors. Six months postoperatively, the patient developed a cervicothoracic kyphotic deformity, requiring instrumented dorsal segmental fixation from C5-T5.

neurofibromatosis type 2 secondary to multiple intracranial and intraspinal tumors. Six months postoperatively, the patient developed a cervicothoracic kyphotic deformity, requiring instrumented dorsal segmental fixation from C5-T5.

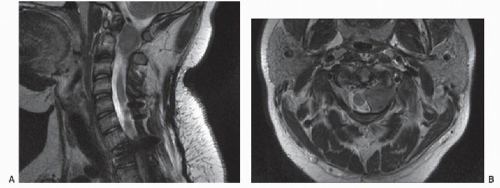

The upper cervical lesion demonstrated interval growth with spinal cord compression (Fig. 54.4A and B). Surgery was recommended, and the patient was taken to the operating room for a C1 hemilaminectomy and resection of the C1-C2 intradural extramedullary lesion. Gross total resection was achieved, and the dura was closed primarily. Pathology was consistent with a meningioma. Postoperatively, the patient was at his baseline with 5/5 motor strength in all extremities, and MRI 2 days after surgery showed excellent spinal cord decompression with minimal residual enhancement at the ventral aspect of the resection cavity (Fig. 54.5A and B).

INTRODUCTION

W. R. Gowers and Victor Horsley described the first surgical resection of an intradural spinal cord tumor in 1888. The patient, a 42-year-old male with progressive paraplegia, underwent resection of an extramedullary “fibromyxoma” at T4 with excellent resolution of his lower extremity weakness (1, 2 and 3). In the early 1900s, Harvey Cushing performed 60 operations for spinal cord neoplasms, including meningiomas, neurofibromas, sarcomas, ependymomas, and astrocytomas (1). These early reports were followed by the seminal work of Elsberg (4) who published the first detailed textbook on the subject in 1916, entitled “Diagnosis and Treatment of Surgical Diseases of the Spinal Cord and Its Membranes.” Two additional texts by Elsberg followed in 1925 and 1941, greatly advancing the field (5, 6 and 7). Today, advances in diagnostic imaging, intraoperative neurophysiologic monitoring, and surgical equipment and techniques have made the resection of intradural spinal cord tumors commonplace in current neurosurgical practice.

CLASSIFICATION

Tumors of the spinal cord account for four to eight percent of all central nervous system neoplasms (8, 9 and 10). They are less common than intracranial lesions with an overall prevalence of approximately one to four and are similar in incidence based on gender, although meningiomas are more common in females and ependymomas more common in males (11). Spinal cord tumors can occur in both the pediatric and adult populations, with tumor histology often dictating the spinal region of origin (3).

The location of cervical intradural spinal cord tumors is generally classified in reference to the spinal cord parenchyma. Intradural extramedullary tumors, arising outside of the spinal cord but within the intradural compartment, can originate from the meninges or the exiting nerve roots. The most common intradural extramedullary cervical spine lesions include schwannomas, neurofibromas, and meningiomas. Intradural IMSCTs, alternatively, originate from the substance of the spinal cord. The most common cervical spinal cord neoplasms arising in this location include astrocytomas, ependymomas, and gangliogliomas (12). Overall, intradural extramedullary spinal cord tumors are much more common than their intramedullary counterparts (11).

Spinal nerve sheath tumors, including schwannomas and neurofibromas, are the most common spinal cord tumors, accounting for approximately one-quarter to onethird of all spinal neoplasms (10,11,13,14). There is no clear difference in prevalence based on sex, and presentation generally occurs in the fourth to sixth decades of life (11,14,15). They originate from neoplastic Schwann cells, with schwannomas most commonly arising from the dorsal root while neurofibromas are more likely to be associated with the ventral root (11). Schwannomas typically grow on the periphery of the spinal nerve as opposed to neurofibromas that diffusely expand the root itself. Spinal nerve sheath tumors are most frequently located in the intradural extramedullary space; however, they can occur in the epidural or paraspinal region, and rare cases of intramedullary origin have been reported (11,15). Due to the comparatively shorter length of the cervical spinal nerve roots within the intradural compartment, cervical nerve sheath tumors frequently present with both an intradural and extradural component and can expand outside of the spinal canal (14). Multiple nerve sheath tumors can be found in patients with neurocutaneous syndromes such as neurofibromatosis type 1 or 2 (NF1, NF2); however, malignant transformation is rare and carries a poor prognosis (11).

Spinal meningiomas are another common lesion arising in the cervical intradural extramedullary compartment and account for approximately 20% of all spinal cord tumors (10,13). They are three times more likely to

occur in females compared to male patients and typically present in the fifth to seventh decades of life (11,16). Spinal meningiomas arise from arachnoid cap cells within the dura in proximity to the nerve root sleeve and are typically firm, encapsulated masses, although en plaque growth can occur (11,16,17). While not as common as the thoracic region, the upper cervical spine and foramen magnum are frequent locations for spinal meningiomas where they often lie in a ventral or ventrolateral location and can adhere to the vertebral artery at its dural insertion (11). Lower cervical spine lesions are less frequent, however (11). Meningiomas are typically solitary and intradural, although approximately 10% extend into the extradural space (11,16). A lateral location in relation to the spinal cord is more common than dorsal or ventral and, although gross total resection is often curative, spinal meningiomas can recur, and recurrence is associated with worse outcomes (16,17). Atypical and anaplastic meningiomas are more likely to recur after surgery and can rarely metastasize (16). Spinal meningiomas have also been associated with NF2.

occur in females compared to male patients and typically present in the fifth to seventh decades of life (11,16). Spinal meningiomas arise from arachnoid cap cells within the dura in proximity to the nerve root sleeve and are typically firm, encapsulated masses, although en plaque growth can occur (11,16,17). While not as common as the thoracic region, the upper cervical spine and foramen magnum are frequent locations for spinal meningiomas where they often lie in a ventral or ventrolateral location and can adhere to the vertebral artery at its dural insertion (11). Lower cervical spine lesions are less frequent, however (11). Meningiomas are typically solitary and intradural, although approximately 10% extend into the extradural space (11,16). A lateral location in relation to the spinal cord is more common than dorsal or ventral and, although gross total resection is often curative, spinal meningiomas can recur, and recurrence is associated with worse outcomes (16,17). Atypical and anaplastic meningiomas are more likely to recur after surgery and can rarely metastasize (16). Spinal meningiomas have also been associated with NF2.

IMSCTs account for 10% to 25% of spinal cord neoplasms. Derived from neuroepithelial tissue, they lie intrinsic to the cord and displace the ascending and descending fiber tracts laterally as they expand. The most common types of IMSCTs include ependymomas, astrocytomas, and gangliogliomas, and the prevalence of each subtype varies with age. For instance, ependymomas are the most common IMSCTs in adult patients, while astrocytomas predominate in the pediatric population, accounting for 90% of intramedullary tumors in children under 10 years of age and 60% in adolescents (3,11).

Excluding the filum, the most common intramedullary location for ependymomas is in the cervical region (11). Astrocytomas are also most common in the cervical spine, with 60% occurring in the cervical and cervicothoracic region (3,11). Ependymomas are typically benign lesions that are unencapsulated, well circumscribed, and noninfiltrating. Astrocytomas are also generally benign, although malignant astrocytomas and glioblastomas comprise approximately 10% of these lesions (11,18). Astrocytomas are unencapsulated; however, in comparison to ependymomas, they are often diffusely infiltrating and lack a well-defined border for resection.

When evaluating a cervical spinal cord tumor, other entities must also be considered in the differential diagnosis. Although nerve sheath tumors, meningiomas, ependymomas, and astrocytomas make up the bulk of neoplasms in this location, other tumors can occur. For instance, hemangioblastomas are benign vascular tumors that make up 3% of all intraspinal neoplasms (19). They are typically intramedullary in location but can rarely arise in the extramedullary space in the cervical spine (19,20). Seventy to eighty percent are sporadic, isolated lesions, although spinal hemangioblastomas also frequently occur in the setting of von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease (19,21). While the sporadic form can be found anywhere in the spine, hemangioblastomas in the setting of VHL have a predominance for the cervical region (11). Other rare spinal cord neoplasms that must be considered include metastases, lymphoma, germinoma, and solitary fibrous tumors (10,22,23).

In addition to neoplastic disease, vascular lesions including cavernous malformations, arteriovenous malformations, arteriovenous fistulas, and aneurysms can also be found in the intramedullary or extramedullary space (24). Cystic and benign entities, such as intradural juxtamedullary cysts, arachnoid cysts, and lipomas, and inflammatory/infectious lesions, including transverse myelitis, sarcoidosis, multiple sclerosis, and subdural empyemas, must also be considered in the evaluation of cervical spinal cord masses (25).

PRESENTATION AND DIAGNOSTIC IMAGING

The clinical presentation of cervical intradural tumors is highly variable (3,17,18). Lesions in both the intramedullary and extramedullary space can remain asymptomatic for long periods of time due to their generally benign nature and growth pattern (3,17,18). High-grade lesions, alternatively, often present with a more rapid onset. Pain is generally the first complaint and can be local or radicular depending on the location of the lesion (3,16,18,26). Patients can also presentwith vague, nonspecific complaints. Sensory disturbances are common and include dysesthesias, loss of sensation, and derangements in proprioception due to compression of the dorsal columns. Weakness can also occur in a radicular pattern with extradural lesions or diffusely at or below the level of the neoplasm with IMSCTs. In children, weakness in the setting of IMSCTs may manifest as clumsiness or frequent falls, while sensory deficits are much less common (3). One-third of children may also presentwith scoliosis due to intramedullary lesions (3).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree