34 Lesions of the Petrous Apex

Carl H. Snyderman, Emiro E. Caicedo, Daniel M. Prevedello, Ricardo L. Carrau, Paul A. Gardner, and Amin B. Kassam

Introduction

Introduction

Surgical approaches to the petrous apex include transtemporal, middle cranial fossa, and transsphenoidal approaches. Lateral transtemporal approaches to the petrous apex may not be possible when there is poor pneumatization of the temporal bone, and continued aeration of the petrous apex may be difficult to maintain. A transcranial middle fossa approach is technically difficult and also suffers from the lack of a permanent drainage pathway. Risks of lateral approaches include brain injury, facial paralysis, hearing loss, and vestibulopathy.

The transsphenoidal approach to the petrous apex was first described in 1977 by Montgomery.1 Subsequent reports have established the utility of an endoscopic transsphenoidal approach in adult and pediatric patients, primarily for cholesterol granulomas.2,3

Indications and Advantages

Indications and Advantages

A completely endoscopic endonasal approach provides direct access to the petrous apex for the treatment of cholesterol granulomas (Fig. 34.1), petrous apicitis, and primary (chondrosarcoma, chordoma, squamous cell carcinoma) and metastatic neoplasms.4–8

Potential advantages of an endonasal approach include avoidance of a craniotomy, minimal postoperative symptoms, faster recovery, a cosmetically acceptable result, and shorter hospitalization. The risks of a lateral approach are avoided, and a permanent drainage pathway is created.

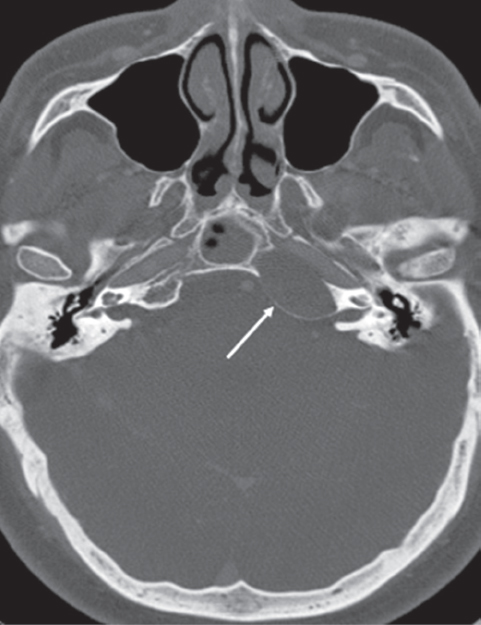

Fig. 34.1 Axial computed tomography (CT) angiography showing a left petrous apex lesion (white arrow) with expansion posteriorly and medially in the direction of the sphenoid sinus. It is an example of a cholesterol granuloma that can be resected by an endonasal endoscopic medial petrous apex approach.

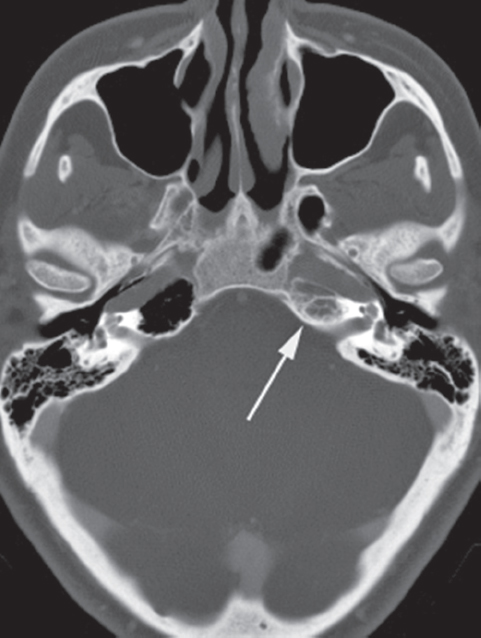

Fig. 34.2 Axial CT angiography showing a left petrous apex lesion (white arrow) with minimal expansion. This cholesterol granuloma is located behind the left internal carotid artery (ICA), and it would require an endoscopic endonasal infrapetrous approach for resection.

Contraindications

Contraindications

A medial approach to the petrous apex is contraindicated when there is no medial expansion of the lesion into the sphenoid sinus (Fig. 34.2) or the lesion is situated inferior to the plane of the petrous internal carotid artery (ICA). An infrapetrous approach should only be attempted by experienced endoscopic skull base surgeons with secure knowledge of the ICA’s endonasal anatomy and with experience in exposing the petrous ICA.

Diagnostic Workup

Diagnostic Workup

Patients with petrous apex lesions often have nonspecific symptoms such as headache, disequilibrium, and tinnitus. A thorough evaluation including assessment of cranial nerve function, nasal endoscopy, audiogram, vestibular testing, and radiologic imaging should be performed when indicated to exclude other sources of the patient’s symptoms. Referral to a neurologist for evaluation and treatment of headaches may be considered prior to surgery.

Imaging

Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provide complementary information and are often both necessary to establish a diagnosis. CT provides important information regarding sinus anatomy (pneumatization, variations), medial expansion into the sphenoid sinus, and bone erosion of the carotid canal. MRI helps establish a diagnosis, and differentiates among cholesterol granuloma, petrous apicitis, and neoplasia.

Surgery

Surgery

Instrumentation

Essential equipment includes a standard array of endoscopic sinus surgery instruments, Kerrison rongeurs, endoscopic bipolar electrocautery, an endoscopic drill with 3- and 4-mm extended hybrid diamond bits, hemostatic materials, and a Silastic stent. A warm water bath maintained at 40°C provides warm saline for irrigation to promote hemostasis.

Operative Setup

The patient is placed in the supine position with neurophysiologic monitoring (somatosensory-evoked potentials) to measure cortical function in case there is injury to the ICA. The head is placed in a Mayfield holder, and registration of the image guidance system is performed. The surgical team is positioned on the right side of the patient, across from anesthesia.

Preparation

The nasal mucosa is decongested with pledgets soaked in 0.05% oxymetazoline and a third- or fourth-generation cephalosporin is administered intravenously for perioperative prophylaxis. The nasal vestibule is prepped with an iodine solution, and the abdomen is similarly prepped in case a fat graft is needed for reconstruction.

Medial Approach (Fig. 34.1)

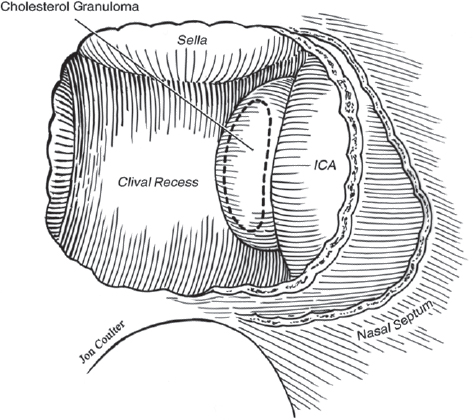

A bilateral sphenoidotomy is performed with wide resection of the sphenoid rostrum and posterior septal attachment. This provides binostril access, with greater room for instrumentation and increased angles for viewing. The vascular pedicle for a septal mucosal flap can be preserved on the side opposite the lesion in case it is needed. Sinus landmarks are identified and intrasinus septations are removed with the drill. Mucosa is stripped from the clival recess and lateral wall to fully visualize the bony anatomy. Usually the petrous apex lesion is readily apparent due to bony expansion medially at the level of the clival recess (Fig. 34.3).

Fig. 34.3 Drawing demonstrating the medial projection of the petrous apex when it is expanded by a cholesterol granuloma immediately behind the ICA.