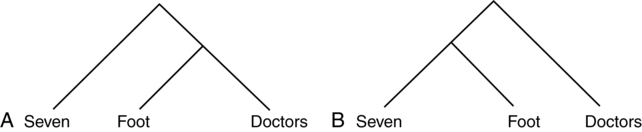

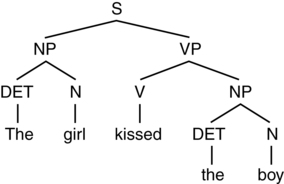

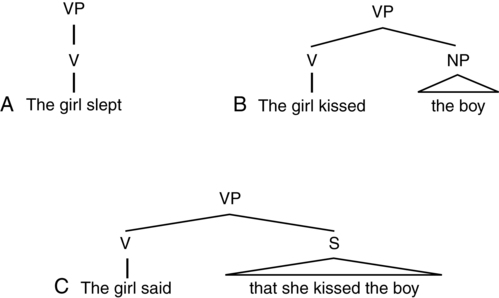

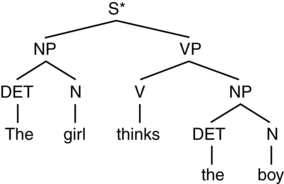

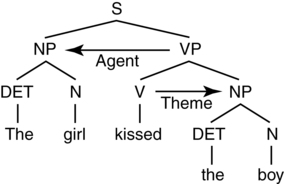

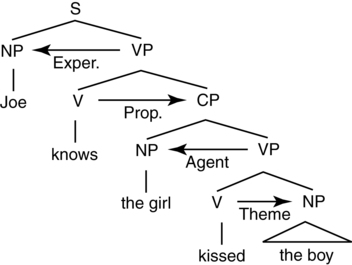

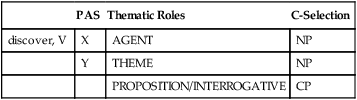

CHAPTER 6 Josée Poirier and Lewis P. Shapiro • Their properties help determine the syntax of the sentences in which they are inserted. • They have features that constrain the semantics of sentences. • They are the “motor” of the proposition expressed in the sentence. These three sequences of words seem to express the same proposition (kissed: John, Mary), yet the order of the words is distinct in each case. Moreover, in the 1950s (considered to be the time when the “modern era” in linguistics and psycholinguistics began) George Miller and his colleagues conducted several experiments that showed that the accurate perception of words in noise significantly increases when the words are strung together into sentences. Thus, at the very least, the sentence holds a privileged role in perception and production, and it will turn out, in comprehension as well.1 Another way of describing or viewing this structural ambiguity is through the use of hierarchical tree structures. Consider again (5a) and (5b) but represented graphically as depicted in Figure 6-1. In fact, what we have done in Figure 6-1 is compute an approximation of phrase structure, which describes the phrasal geometry of sentences. These are node-labeled tree structures with hierarchical ordering. There are lexical nodes, which refer to lexical categories (i.e., parts-of-speech), like N (Noun), V (Verb), and P (Preposition). These lexical categories form the heads of the higher-order phrases to which they project.2 So, the Verb is the head of the Verb Phrase (VP), the Preposition the head of the Prepositional Phrase (PP), and so on. Consider Figure 6-2. The syntactic component of the grammar includes an operation, MERGE, which takes two categories as input and then outputs a single, merged, category. So, in Figure 6-2, the Determiner and Noun merge to form a higher-order NP; the Verb and NP merge to form a higher-order VP, and the VP and subject NP merge to form the Sentence. Continuing, and keeping with the focus of this section, we now consider only the VP. VPs expand to include several possibilities; Figure 6-3 shows only three. In (a), the verb sleep has no complements; that is, it has nothing that comes after it. In (b), the verb kiss takes an NP complement. Thus, the V merges with an NP and yields the VP (or alternatively, we can say that the VP expands to include an NP complement). Finally, the verb say merges with a complement phrase/sentential clause (S) to form the VP. In this case, the embedded S would, itself, expand (as shown in Figure 6-2). So, each verb selects a particular syntactic structure. In this way, we have shown that verbs directly influence the syntax of the sentences in which they are contained. To generate a sentence, we begin by enabling a set of lexical items (technically, a numeration) and then use successive merger operations. For example, beginning with the numeration: [Kiss; V; girl, boy], we would merge the Verb kiss with its NP (boy) to form the VP (see (8b)). We then select girl, which is an NP, and merge this with the previously formed VP, to yield the Sentence Node (see Figure 6-2 for more details). Note that the successive merger operations are not intended to mimic real-time processing of sentences (if it did, we would be parsing sentences backward!); instead, Merge is considered a linguistic operation. It remains for empirical work to discover if Merge has psycholinguistic consequences (and indeed, as we shall show shortly, there is such evidence). We now consider another example, with the verb think [thinks, V; girl, boy] substituting for the verb kiss. So, in Figure 6-4, we go through successive merger operations (i.e., DET merges with N to form an NP, V merges with NP to form VP, NP and VP merge to form an S) to derive the sentence: “The girl thinks the boy.” Of course, our intuitions strongly suggest a distinction between the output of Merge in (see Figure 6-3, B) relative to the output in (see Figure 6-4); the former is well-formed or grammatical (“the girl kisses the boy”), while the latter is ill-formed or ungrammatical (*“the girl thinks the boy,” with * signifying a sentence is ungrammatical). Merge seems to be too powerful as we have used it here—it generates both grammatical and ungrammatical sentences. Thus we need a way to restrict the output of Merge to include only well-formed sentences. The solution turns out to involve verb properties; these will allow the theory to form only grammatical sentences. We turn to this solution in subsequent sections. Consider the following verbs and the sentences in which they are contained: Each verb needs partners to describe an event or activity. The verb disappear requires one participant as shown in (6a); the verb kiss, shown in Figure 6-4 as well as in (7a), needs two participants; and the verb put requires three as shown in (8a). To see that this is true, consider the (b) versions above, which are all ungrammatical. That is, disappear cannot occur in a sentence with two participants; kiss cannot appear in a sentence with only one participant; and put cannot appear in a sentence with two participants (or even one, as in *the girl put). Thus, verbs, again, are said to select their sentence environments. Semantics also plays an important role in argument structure. Consider the following examples3 : Thematic Role: The semantic type played by an argument in relation to its predicate. In (15) the subject NP, the girl, plays the role of the Agent of the event, and the boy, the Theme. Let’s assume that these properties are represented with the verb as part of its entry in the Lexicon. Consider again the verb kiss and its predicate argument structure (PAS) and thematic role features (presented in Table 6-1). The lexical entry table shows that kiss, a verb, requires two arguments, designated by X and Y. The two arguments have particular thematic roles that need to be assigned (AGENT, THEME). Let’s assume that thematic roles are essentially features that need to be “checked off” for the sentence to be grammatical. Consider then Figure 6-5. We have already discussed how the verb (V; kissed) merges with an NP (the boy) to form the VP (kissed the boy). We will also assume here that the V assigns a thematic role (THEME) to its NP complement, and thus we have the result appearing in Table 6-2. Once we have assigned the thematic role to the argument position, we check-off the thematic role. As we have also discussed previously, the VP merges with the subject NP (the girl). As part of this Merge operation, the VP assigns the thematic role of Agent to the subject argument and thus we have the final result in Table 6-3. Given the lexical entry for any particular verb, if there are not enough argument positions in the sentence for the thematic roles to be assigned, or if there are too many argument positions given the number of thematic roles, then the derivation of the sentence will “crash” and the result will be an ungrammatical sentence. To see what we mean, consider Table 6-4. The verb put requires three arguments. Given the sentence: Only two arguments are active in the sentence (the subject and object NPs, the girl and the boy, respectively). Thus, when thematic roles are assigned to these argument positions, there is one thematic role left in the lexical entry that has not been checked-off (Table 6-5). Table 6-5 Checking Off Two of Three Required Thematic Roles Because there is a mismatch between the number of arguments required by the verb (see Table 6-4) and the number of arguments active in the sentence (see (19)), the features of the verb are not satisfied in the sentence, and hence the sentence is ungrammatical. Recall in the previous section that the Merge operation, by itself, is too powerful; it generates grammatical as well as ungrammatical sentences. Once we assume that the features of the verb (in this case, the argument structure and thematic role representations) must be accommodated in the sentence, the output of Merge will then be constrained to form only grammatical sentences. On some accounts, not only are NPs arguments of the verb, but so too are more complex embedded sentential clauses or Complement Phrases (CPs) (Grimshaw, 1977; Shapiro, Zurif, & Grimshaw, 1987, Shetreet, Palti, Friedmann, & Hadar, 2007). Consider the following three verbs: 20a. Yosef knows [NP the time]. 20b. Yosef knows [CP that the girl kissed the boy]. 20c. Yosef knows [CP who the girl kissed]. 21a. Yosef asked [NP the time]. 21b. *Yosef asked [CP that the girl kissed the boy]. 21c. Yosef asked [CP who the girl kissed]. 22a. *Yosef wonders [NP the time]. 22b. *Yosef wonders [that the girl kissed the boy]. As can be seen in (20)–(22), the verbs know, ask, and wonder have distinct selectional requirements; know and ask select for an NP argument while wonder does not, and all three select for a complement phrase (CP). Notice that the CP takes two different forms, one where it is headed by the complementizer that, as in (20b), while another is headed by the complementizer who, as in (20c)–(22c). These phrases are associated with complex semantic types (Grimshaw, 1977): 23a. Yosef knows [NP the time] 23b. Yosef knows [CP that the girl kissed the boy] 23c. Yosef knows [CP who the girl kissed] Those headed by a that-phrase are typically Propositions, while those headed by a wh-phrase are typically Interrogatives (there are additional semantic types, such as Exclamations and Infinitives; see Shetreet et al., 2007). Notice that these complex arguments have internal structure. Taking (23b) as an example, the argument playing the role of Proposition can be further divided into an AGENT THEME structure, where the embedded subject argument, the girl, is assigned the AGENT role and the embedded object argument, the boy, is assigned the THEME role. Thus, a complex sentence with an embedded clause must satisfy the lexical requirements of two verbs. This can be seen in Figure 6-6. As shown in Figure 6-6, when the embedded V (kiss) is merged with its NP complement (the boy), the THEME role is assigned (and checked-off) and a VP is formed. Moving up the tree, when the resulting VP is merged with the subject NP (the girl), the AGENT role is assigned and a CP is formed. Continuing, when the embedded clause (CP; the girl kissed the boy) is merged with the main verb (know), the PROPOSITION is assigned and a VP is formed. Finally, when the resulting main VP (knows (that) the girl kissed the boy) is merged with the main subject NP (Joe), the EXPERIENCER role is assigned and the S is formed4 ,5 . 25. The girl pushed [NP the boy]. 26. The girl gave [NP the prize] [PP to the boy]. 27. The girl thought [CP that the prize was nice]. The formal name for the verb’s syntactic properties is syntactic subcategorization, also known as C-selection (Complement Selection). That is, the verb is said to subcategorize for various types of phrasal complements. Now, consider a more fully established lexical entry as in Table 6-6. Table 6-6 Partial Lexical Entry for the Verb “Discover” The entry shown in Table 6-6 describes the following properties of the verb discover: It has a two-place argument structure; the second (Y) argument can C-select either an NP or a CP. If there is a direct object NP argument active in the sentence, it will be assigned the Theme role; if that argument is, syntactically, an embedded clause (CP), then it will be assigned either a PROPOSITION or an INTERROGATIVE. The lexical properties of the verb will thus yield the following example sentences: 28a. Richard [discovered [NP the fish]] 28b. Richard [discovered [CP that the fish was in the soup]] Given its contributions to the syntax and semantics of sentences, it should not be too surprising that verb representations have played a significant role in accounts of sentence processing. In perhaps the first attempt to examine how verbs influence sentence processing, Fodor, Garrett, and Bever (1968) found that sentences that contained verbs that accommodated two possible syntactic configurations—an NP or CP (S) complement—were more difficult to process than sentences containing verbs that accommodated only a single configuration—an NP complement. They found this to be so even though the sentences to be processed took the simplest form and were syntactically identical NP-V-NP transitive constructions. Thus, it was the verb’s potential to accommodate different syntactic structures (i.e., their implicit lexical representations), and not the surface realization of one or the other of these structures, that appeared to contribute to sentence processing performance. Fodor et al. (1968) used paraphrase and anagram tasks to discover the relation between the complexity of verb representations and sentence processing performance. Similar findings were reported by Holmes & Forster (1972) using rapid serial visual presentation (RSVP) and by Chodorow (1979) using time-compressed speech. In a related series of experiments, Shapiro and colleagues (e.g., Shapiro, Zurif, & Grimshaw, 1987, 1989; Shapiro, Brookins, Gordon, & Nagel, 1991) discovered the relation between the number of argument structure configurations and sentence processing complexity, using a cross-modal lexical interference task (Box 6-1). Briefly, verbs accommodating different numbers of argument structures were inserted in sentences with similar, simple, surface forms. These sentences were presented to normal listeners, who had to complete a secondary task that was presented in the immediate temporal vicinity of the verb. Verbs that entailed more argument structure possibilities yielded greater processing load relative to verbs that entailed fewer possibilities, suggesting that once the verb is encountered in a sentence, all of its possible argument structure arrangements are activated. One reason for such exhaustive activation is that it allows for on-line thematic role assignment, as we discussed earlier. That is, once the verb is encountered and activated, so too are its argument structure and thematic roles, setting the stage for further operations of the sentence processor (see, for example, Clifton, Speer, & Abney, 1991; Pritchett, 1988; Boland, Tanenhaus, & Garnsey, 1990). Also, our foray into the syntax of movement has important implications for sentence processing. As we shall show shortly, when a listener who is attempting to understand a sentence encounters a direct object position that is “empty”—where the direct object NP has been displaced to a position that occurs before the verb—the listener appears to activate that NP, even though it is not heard or seen at the post-verb position. This is a remarkable finding, and suggests that linguistic theory does have something to offer those of us who are interested in how the brain comprehends language. Furthermore, constructions with movement turn out to be particularly problematic for some individuals with aphasia, as Chapter 10 reveals. With these linguistic preliminaries out of the way, we now turn to sentence processing.

Linguistic and psycholinguistic foundations

Linguistics toolkit

Merge and phrase structure

Argument structure

Thematic roles

Lexical entries

PAS

Thematic Roles

put, V

X

AGENT 3

Y

THEME

Z

GOAL

Complex arguments

Syntactic features of arguments

PAS

Thematic Roles

C-Selection

discover, V

X

AGENT

NP

Y

THEME

NP

PROPOSITION/INTERROGATIVE

CP

Argument structure, copies, and sentence processing

Neupsy Key

Fastest Neupsy Insight Engine