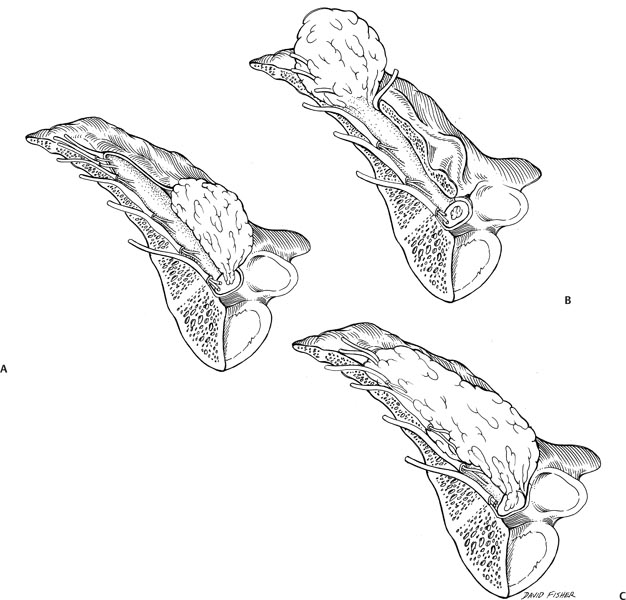

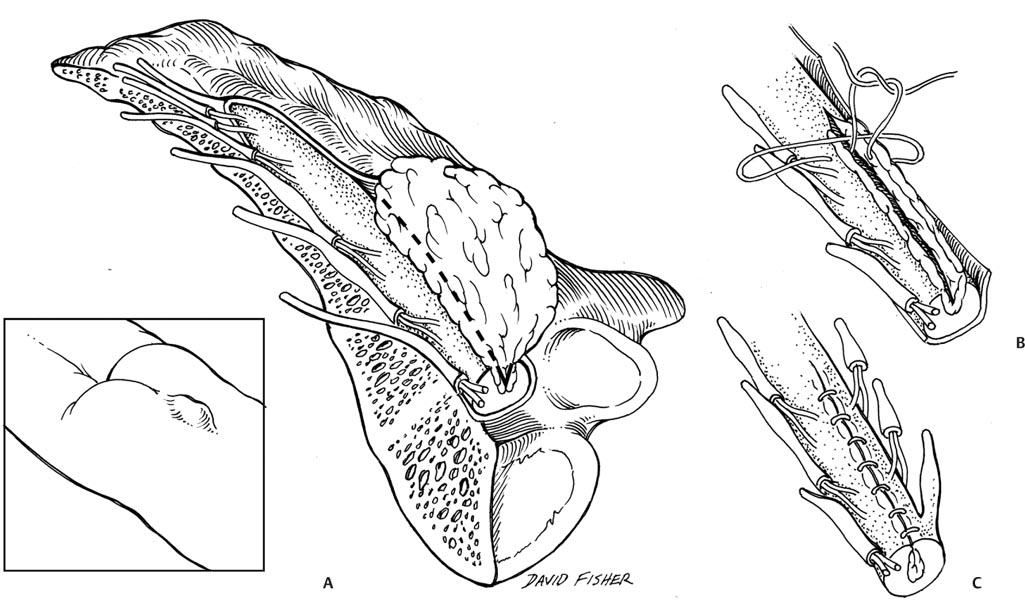

17 Lipomyelomeningocele/Tethered Cord Spinal cord tethering and the tethered cord syndrome are seen with relative frequency in pediatric neurosurgery. Seen primarily in cases of myelomeningocele, occult spinal dysraphisms, and thickened or fatty fila terminale, as well as secondarily following closure of spinal dysraphisms, traction on the spinal cord results in several neurologic, uro-logic, and orthopedic sequelae. Limited data exist on the incidence and natural history of tethered spinal cord; however, there is evidence to suggest that patients whose spinal cord is tethered will demonstrate progressive injury in the form of pain, sensory loss, weakness, bladder dysfunction, and orthopedic deformity. Furthermore, the clinical picture may not improve completely following release of the tethered spinal cord. The challenge facing pediatric neurosurgeons is determining if the progressive neurologic deficit can be avoided with prophylactic surgical intervention, and if so, at what cost? Should we wait until the child develops symptoms, which may be irreversible, or act prophylactically and accept the risks of potential neurologic injury at the time of surgery? The balance lies in understanding the true surgical risks to the patient and the expected efficacy of surgical intervention. In coming to this understanding, we must consider each of the clinical conditions causing spinal cord tethering separately and acknowledge that patient age and surgeon experience play an important role in the overall outcome. The conclusion that tethered spinal cord leads to progressive neurologic injury and subsequent neurologic, urologic, and orthopedic disability comes from observations of clinical series that older patients generally present with more serious symptomatology. Neonates and infants often present with cutaneous stigmata of occult spinal dysraphism and tethered spinal cord and normal neurologic function.1–7 Older children and adults are more likely to present with neurologic or urologic dysfunction, orthopedic deformity, and pain.7–10 Few studies have followed the natural history of asymptomatic tethered spinal cord; however, with time, it is clear that neurologic and urologic deficits develop and may not be reversible with surgery.7,8,11 Hoffman et al reported on 97 patients with lipomyelomeningoceles.7 They found that of those presenting in the first 6 months of life, 35 of 56 (62%) had a completely normal neurologic exam. In contrast, only 12 of 41 patients (29%) over the age of 6 months were normal. Early treatment was associated with maintained or, in some cases, improved neurologic function, whereas delayed surgical untethering resulted in poorer neurologic outcome.7 Thus, although prophylactic surgery has the risk of inducing neurologic injury, early surgery before symptoms develop offers the best opportunity for normal neurologic function. Similarly, Kanev and Bierbrauer showed that asymptomatic patients having lipomyelomeningocele repair and release of spinal cord tethering retained intact bladder function.8 That said, detethering operations, particularly of lipomyelomeningoceles, can be challenging, and procedures performed by the technically excellent general neurosurgeon in this difficult patient population are associated with potentially undesirable outcomes. Myelomeningocele represents the most extreme form of tethered spinal cord. In infancy, the primary goal of closing this type of lesion is to reduce the risk of infection. Closing the placode and reconstructing the dural tube in such fashion as to reduce the risk of retethering is important in the long-term management of patients with spina bifida. Signs and symptoms of delayed retethering include progressive scoliosis, worsening gait in ambulators, back pain, and progressive hand weakness and clumsiness. Retethering should be thought of as a matter of when, not if, following myelomeningocele repair. As such, in following these patients, our clinical suspicion for tethered spinal cord should remain high. We recognize that traction on the distal spinal cord is injurious to neurons and can lead to progressive neurologic deterioration and that such injury is often permanent. Experimental research in animals has demonstrated that traction applied to the spinal cord reduces local blood flow and that both continuous and intermittent traction results in spinal cord ischemia.12–15 Thus, when early clinical deterioration is recognized, we should actively sort out and resolve spinal cord retethering expeditiously so as to maintain neurologic function in these delicate patients. Importantly, as the majority of these patients have associated hydrocephalus, it is imperative to first ensure adequate shunt function when they present with any clinical deterioration. The clinical impact of spinal cord tethering can be so great that in patients who are nonambulatory and have no voluntary bladder and bowel control, a spinal cord transection immediately above the tethering element is warranted.16,17 Lipomas of the conus medullaris and the filum terminale have traditionally been reported as a group as spinal or lumbosacral lipomas. Although their clinical presentation can often overlap, their surgical management and outcome are disparate. Several articles have demonstrated that lipomas of the filum terminale and caudal spinal cord are amenable to surgery with little risk of neurologic injury, whereas dorsal and transitional lipomyelomeningoceles are more difficult owing to the presence of functioning nerve roots passing through the lipoma.18–21 Thus, it is important to discuss each of these lesions in turn to better understand the risks of surgery. Lipomas of the conus medullaris with associated spina bifida have been categorized by Chapman into two distinct variants, dorsal and caudal, and a transitional form that has components of both (Fig. 17.1).20 The importance of differentiating lipomyelomeningoceles relates to the relationship of functioning neural tissue within the lipoma. Dorsal lipomyelomeningoceles often have a substantial subcutaneous lipoma continuous with the intradural lipoma through a wide dural defect tethering the spinal cord dorsally. The sensory rootlets emerge from the caudal spinal cord immediately ventral to the fusion line of the lipoma, with the spinal cord and the motor rootlets further ventral. Thus, there are no functional neural elements within the lipoma, which can be resected free from the spinal cord at its interface. Care must be taken when incising the dura lateral to the lipoma to ensure that sensory rootlets are not injured. In contrast, caudal lipomyelomeningoceles may be entirely intradural or extend subcutaneously through an occult spinal dysraphism. The terminal spinal cord enlarges into the lipoma, and the most caudal nerve roots often run within the more fibrous portion of the lipoma anteriorly and anterolaterally. In some cases, these nerve roots are rudimentary, and the nerves serving the bowel, bladder, and lower extremities are free from the lipoma. Intraoperative nerve root stimulation can be valuable in differentiating functional sacral roots from rudimentary roots within the fibrofatty mass, but it is important to stress that aggressive surgical resection of this lipoma carries a higher risk of neurologic injury, particularly to bowel and bladder function. The most difficult lipomyelomeningocele to manage is the transitional type. The line of fusion between the lipoma and spinal cord is dorsal to the sensory rootlets superiorly, but as the mass continues caudally, this line of fusion is displaced ventrally such that nerve roots are found to emerge from the anterolateral aspect of the lipoma. In most cases, these are sensory rootlets; however, there is often greater variability in the relationship between the lipoma and the spinal cord and neural elements in this type of lipomyelomeningocele. The primary goal of surgery is to relieve the spinal cord from mechanical constraint and not necessarily to remove the lipomatous mass in its entirety (Fig. 17.2). Aggressive surgical resection carries increased risk of injury to neural structures, whereas limited resections have an increased risk of retethering. Byrne et al retrospectively reported on the outcomes of children with spinal lipomas and found that those who had a definitive untethering procedure had better long-term neurologic outcome than those who underwent a cosmetic resection of their lipoma, who in all cases, went on to have a symptomatic tethered cord and late postoperative deterioration.22 Additionally, they reported that in those patients presenting with neurologic deficits, 39% improved, and 3% deteriorated following surgery. No asymptomatic patient deteriorated postoperatively, and 93% remained symptom free at 4-year follow-up.22 Surgical experience is of great value in understanding the relationship of the lipoma with the spinal cord to provide the greatest resection safely on the first attempt. Subsequent operations for retethering are always made more difficult due to the presence of scar and the disruption of tissue planes. This is especially true when the neural elements are rotated in the axial plane. Spinal cord tethering by a tight or fatty filum is more straightforward than in the presence of a spinal dysraphism. The principle of surgery is the same: release the mechanical constraint and prevent retethering. Upon opening the dura, nerve roots will often be dorsally displaced and need to be protected from injury. Some authors advocate sectioning the filum immediately as it arises from the conus medullaris, whereas others prefer to open the dural inferiorly over the cauda equina and identify the nerve roots as they exit laterally through the intervertebral foramen and to follow the filum as it continues inferiorly and exits the dura dorsally. The decision as to which technique to employ is surgeon dependent based on personal preference and experience as long as the filum can be definitively identified and sectioned without injury to neural elements and in such a fashion as to avoid retethering. In experienced hands; a reasonable adjunct to filum section is to advance a flexible endoscope both dorsally and ventrally to ensure the absence of a tandem tethering element, such as thickened arachnoid adhesions. A more controversial issue is the management of patients presenting with symptoms related to a tight filum terminale whose imaging demonstrates a normal-lying conus medullaris. Bao et al demonstrated that these patients benefit from early release of their filum terminale and that surgical and pathologic identification of fibrofatty tissue within the filum may not appear on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).23 Unfortunately, the criteria for sectioning the filum with normal imaging have not been clinically established, and the pool of candidate children with bed wetting issues is large. Great care must be taken to limit this procedure to those with intractable medical problems. Fig. 17.1 Schematic drawing of the three primary types of lipomyelomeningoceles. (A) Dorsal lipomyelomeningocele. Note the subcutaneous mass and fascial penetration of the fatty tissue that has tethered the cord distally within the spinal canal. Also notice that the lipoma interdigitates into the dorsal spinal cord posterior to the extension of the dorsal roots. (B) Caudal lipomyelomeningocele. Note the lipomatous mass extended from the terminal and tethered distal spinal cord. Nerve roots are seen extending from the terminal cord and engulfed within the fatty tissue. (C) Transitional lipomyelomeningocele. This is a combination of the dorsal and terminal types. The cord may be rotated, and extreme care must be taken to avoid injuring functioning nerve roots. Fig. 17.2 (A) Artist’s rendition of the plane (dotted line) used for debulking the lipomyelomeningocele. This is an example of a dorsal lipomyelomeningocele. Note that immediately deep to the thoracodorsal fascial defect, there is continuity of the more superficial fat and spinal cord. (B,C) Following debulking, the pial edges of the cord defect are opposed with sutures. In assessing the value of any surgical procedure, the risks and efficacy of the operation must be better than the natural history. This is particularly true for prophylactic operations in which the surgical risks are borne by an asymptomatic patient. Pierre-Kahn and colleagues demonstrated that the surgical risks associated with spinal cord untethering are much better than the natural history. More than half of patients with lumbosacral lipomas (lipomas of the filum terminale or conus medullaris) will show neurologic deterioration with time, whereas surgical release carries low operative risks, and very few patients deteriorate postoperatively.24–26 That said, outcomes following surgery are largely dependent on surgical pathology. Patients with lipomas of the filum terminale have better outcomes than those with lipomas of the conus medullaris or lipomyelomeningocele. This is true in cases of both symptomatic and asymptomatic fatty filum. These patients have lower rates of postoperative deterioration and improved resolution of symptoms. In contrast, patients with lipomas of the conus medullaris have increased risk of delayed deterioration due to retethering, as well as poorer resolution of symptoms and neurologic recovery following surgical untethering. Additionally, patients’ greatest chance for success rests with the first surgeon to release the spinal cord from mechanical tethering, as outcomes following principle untethering are much better than following secondary retethering.27,28 The management of patients with spinal cord tethering remains difficult and somewhat controversial.29 The natural history seems to be one of slow neurologic deterioration, progressive urologic dysfunction and orthopedic deformity, and the development of back pain and radiculopathy. These clinical features are occasionally found in the setting of normal imaging, adding to the complexity of management. In cases of tethered spinal cord secondary to tight or lipomatous filum terminale, the surgical risk-to-benefit ratio is clearly in favor of surgery in both symptomatic and asymptomatic cases. Spinal cord tethering secondary to lipomyelomeningocele or retethering following a spina bifida repair is surgically more complex and is best managed by those experienced with the disorder. That said, asymptomatic patients likely will benefit most from surgical untethering because continuous traction on the spinal cord clearly leads to neurologic injury, and once neurologic deficits exist, they may not be reversible with surgery. For children born with lumbosacral lipoma, progressive neurologic dysfunction due to spinal cord tethering is inevitable. Timely surgery before the onset of symptoms, however, may prevent this deterioration. Such is the philosophy that has prevailed in the pediatric neurosurgical community for more than a half decade.30 Indeed, numerous case series and technical notes have been published that show that mechanical untethering of the spinal cord is technically possible, that operative morbidity is low, and that good outcomes can be achieved in most cases. However, the majority of published series are retrospective, single institution/single surgeon series and have commonly grouped together rather disparate populations. For example, in some series, filar lipomas and complex transitional lipomyelomeningoceles have been considered together under the all-embracing title of spinal lipomas, and in others, both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients have been analyzed together. Most surgeons would agree that the surgery to untether a transitional-type lipoma is a major undertaking, and out of experienced hands, morbidity (neurologic, urologic, and wound related) can be significant. By contrast, division of a lipomatous filum terminale is usually a simple procedure with few complications but enduring efficacy.31–33 Over the past 10 years the dogma that all patients with lipomatous dysraphic malformations should be untethered has been challenged. It has become apparent that the natural history of these conditions may not be as pessimistic as traditionally thought.34 There are several questions that lie at the heart of this neurosurgical controversy: Is it appropriate to consider all lipomas together and apply the same treatment criteria to each? What is their true natural history if left untreated? and How safe and effective is prophylactic spinal cord untethering for this condition? What follows is an attempt to examine some of these questions and suggest that a more critical evaluation of the role of early neurosurgery is now appropriate and that, at least for some patients, a conservative approach with close neurologic and urologic surveillance might result in a better long-term outcome. The classification of lumbosacral lipomas suggested by Chapman35 is perhaps the most widely known. It is anatomically based, describing the position of the neural placode (the point of attachment of the lipoma to the spinal cord) in relation to the conus and posterior nerve roots. Dorsal lipomas are situated on the dorsal aspect of the lower spinal cord but above the conus, caudal types are attached to the termination of the spinal cord, and transitional types are intermediate between these. Transitional types are complex malformations characteristically involving the conus. They have an intimate association with the elements of the cauda equina; the neural placode is frequently rotated to one side, where nerve roots are commonly horizontally disposed due to the low position of the spinal cord and shortened relative to the opposite side. Additionally, such lipomas are frequently large, obliterating the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) spaces and associated with significant deficiencies of the terminal dural sac. Each of these features contributes to the complicated surgical anatomy of these lesions. The embryological basis of lumbosacral lipomas remains unknown. In contrast to the open dysraphic states, there is no animal model in which this entity can be studied. Naidich and associates proposed that these lesions resulted from premature dysjunction.36

Prophylactic Untethering

Clinical Presentation

Myelomeningocele

Occult Spinal Dysraphisms

Lipomyelomeningocele

Lipoma of the Filum Terminale: “Fatty Filum”

Conclusion

Is Surgery Always Necessary?

Classification and Embryogenesis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree