(1)

Hand Surgery Department of Clinical Sciences, Malmö Lund University Skäne University Hospital, Malmö, Sweden

Abstract

Amputation of a hand results in profound synaptic reorganisations in the brain cortex. The cortical representational area of the amputated hand is at first ‘silent’ but rapidly becomes invaded by adjacent cortical areas. Cortical reorganisations can result in phantom sensation, a feeling that the lost hand is still there. Phantom sensation can sometimes be combined with severe phantom pain. Mirror treatment, based on an illusion that the lost hand is still attached, may be an effective way of treating severe phantom pain. Amputated fingers or hands can often be microsurgically replanted (reattached to the body). When a replanted hand is reinnervated, it resumes its correct position in the brain cortex. The salamander is unique among animals since it can spontaneously regenerate an amputated extremity. It has been suggested that the mechanism behind this phenomenon is based on an interaction of stem cell-like cells at the amputation level interacting with a specific Schwann cell-produced protein (nAG). If these mechanisms could 1 day be applied to humans, it would open up a totally new landscape for treating amputations.

Losing a hand is catastrophic, an event that may have lifelong consequences. There are several reasons for accidental hand amputation. I have had patients who walked into the rotating propeller of a small airplane or tilted a motor-driven lawnmower or were not sufficiently cautious while working with a saw or handling fireworks on New Year’s Eve. Sometimes, an arm can be amputated by choice, because of tumours.

In addition, children can be born without a hand or an arm as a type of congenital malformation. Whatever the reason, the consequences can be quite severe. Many patients perceive the amputation as a mutilation of both body and identity, a psychological trauma that can be very hard to accept and that can create a personal crisis. The amputation may make it difficult to continue one’s occupation, and major adjustments in daily life may be necessary. It may also be a cosmetic problem that can be difficult to handle emotionally.

Phantom Sensation and Phantom Pain

A common complication after an amputation is a phantom sensation, a feeling that the amputated hand is still in place [1–5]. The phantom sensation may be enormously painful. The experience is often frightening and quite obvious, many times with a feeling that individual fingers are moving or maybe locked in painful contractures, sometimes so severely it feels as if the nails are being forced into the palm. Some patients feel that they can move the fingers of the phantom hand, while others feel as if it is totally paralysed. Often phantom sensation is linked to a severe phantom pain that can be burning, cramp-like or stabbing.

What Happens in the Brain After a Hand Amputation?

Phantom sensation and phantom pain are based on the very prominent functional reorganisations in the brain cortex that follow an amputation [6, 7]. Amputation of a hand or an arm results in rapid changes in the cortical body map [8–11]. The cortical representation of the hand is normally quite large in the sensory and motor cortices, but after an amputation there is no longer a sensory inflow from the hand. The hand projection in the cortical body map suddenly becomes silent, and this area becomes ‘vacant’ and unused: there is a ‘black hole’ in the brain. The brain is rational and does not accept silent areas. Within minutes and hours there is a functional reorganisation in the synaptic connections. The adjacent cortical projectional areas corresponding to the face and the residual part of the forearm now expand over what previously belonged to the hand, and the nerve cells in this area now make new functional connections. Among several consequences of amputation of an arm is a change in the face’s sensory functions. After only 24 h, there may be obvious indications of functional reorganisations in the somatosensory cortex, where the face representation expands over the previous hand-arm representation [9, 12–15]. The result is often a ‘mapping’ of the hand in the face so that touching various parts of the face results in sensations in various parts of the non-existent phantom arm [3].

After a hand amputation, there is often a ‘mapping’ of the lost hand on the skin of the residual part of the forearm [3, 15–18]. This is presumably a consequence of the cortical reorganisations that occur after the amputation, including the expansion of the adjacent forearm representation, just as the amputation of a finger results in the expansion of the adjacent cortical representations in the somatosensory cortex of nearby fingers (Fig. 14.1). Following the amputation of an index finger, the cortical projections of the thumb and long fingers expand so that these fingers take over the area that previously belonged to the index finger [6, 9, 19–22].

Fig. 14.1

Functional reorganisation occurring in the sensory cortex following amputation of an index finger. When a finger is amputated (a, b), a corresponding ‘silent’ area occurs that is rapidly occupied by the adjacent representational areas corresponding to the thumb and middle finger (c, d)

The functional reorganisation that occurs in the brain cortex following amputation is the primary reason for the feeling that the amputated body part is still intact. Sometimes the phantom sensation can be linked to phantom pain, which can sometimes be extreme and almost impossible to endure [14, 23–25]. It is well known that the intensity of phantom pain is in proportion to the extent of the synaptic reorganisations in the brain: the more extensive the reorganisation, the more the pain [23, 26]. Usually phantom limbs are perceived in the location previously occupied by the intact limb, but sometimes they can retract inside the stump, a phenomenon referred to as ‘telescoping’. Telescoping is relevant from a clinical point of view, as it tends to be related to increasing levels of phantom pain [27].

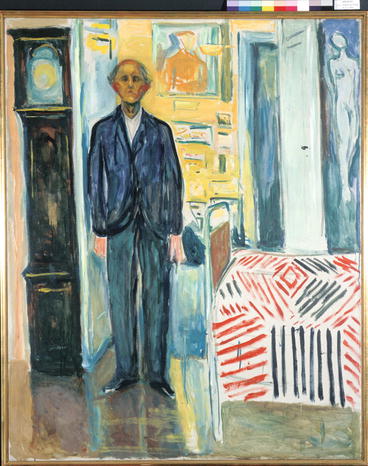

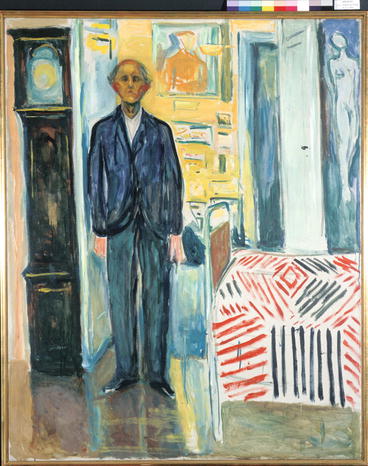

The Norwegian artist Edvard Munch dramatically depicted the intensity of phantom pain in a self-portrait after he lost a finger (Fig. 14.2). Munch had a traumatic relationship with Tulla Larsen, the rich daughter of a wine merchant. When their relationship ended in 1902 after an unsuccessful attempt at reconciliation, Munch, in despair, shot himself in his right hand so that his index finger was amputated. In a self-portrait, Munch expressed the despair, vulnerability and defencelessness that he felt after the episode. He was affected by extremely painful phantom sensations including a component of phantom pain, something that, in his self-portrait, he illustrated by painting the non-existing index finger green in its normal position.

Fig. 14.2

Edvard Munch. Self-Portrait. Between the Clock and the Bed, 1940–1943. Munch lost his left index finger in a shooting accident. The missing finger is painted in green to illustrate that it in fact is a ‘phantom finger’ with constant pain. Oil on canvas, 120.5 × 149.5 cm (© Munch-Museet/Munch-Ellingsen gruppen/BUS 2013)

Mirror Training: A Way to Treat Phantom Pain

The extent of phantom sensation and phantom pain is proportional to functional changes of the amputated body part’s representation in the brain. But if the modified mapping of the amputated body part could somehow be normalised, perhaps the phantom pain would disappear. Such a treatment principle was first described by Ramachandran [3, 28]. The strategy is to create an optical illusion of the lost hand so that the brain gets an impression that the hand is in its normal position. This is done by placing a mirror in front of the amputee in a somewhat oblique position (Fig. 14.3). By creating a reflection of the non-amputated hand in the position of the lost hand, an illusion is created; when the patient looks in the mirror observing the mirror image, he sees a normal hand in the position of the lost hand. If the normal hand is activated so that the corresponding movements occur in the mirror picture, the illusion becomes even stronger; the visual impression is that the lost hand is not only in place but that it even functions. The visual impression of the hand being reattached may presumably induce a normalisation of the modified cortical hand-arm representation, resulting in relief or the disappearance of the phantom pain. The treatment, in its original or a modified form, has to be repeated several times but can ultimately have a positive effect [5, 29, 30].

Fig. 14.3

‘Mirror treatment’ of severe phantom pain after amputation of the left arm and hand. A reflected mirror image of the intact right hand in the position of a normal left hand gives an illusion of the left hand being reattached to the body in its correct position

Thus, creating an optical illusion that the amputated hand is in its usual position may be a way to treat phantom pain. But the best way to deal with the potential problem is, of course, to perform a surgical reattachment of the hand as soon as possible after amputation – a replantation.

Hand Replantation

The concept of reattaching amputated extremities can be traced back to the Renaissance and even earlier. In several Christian religious paintings, there are examples how severed hands and arms were miraculously reattached to the body [31]. In a painting by Giovanni di Paolo from the fifteenth century, a child’s right arm was amputated by a wolf. A miraculous replantation was performed by Saint Clara of Assisi who first killed the wolf and then reattached the arm after it had been retrieved from another friendlier wolf. Other examples include the replantation of a thumb, depicted by an anonymous artist, the master from Novara, in a fresco painting from the fifteenth century in a northern Italian Benedictine monastery. The painting shows how Saint Julius from Novara replanted the thumb with the help of the cross sign: ‘he made the cross-sign and the hand became again as usual’ [31].

Saint Julius’ miraculous ability was envied; replantation is much more difficult for today’s surgeons. The last four decades have seen dramatic improvement in the replantation process. In the 1960s, it was argued that an amputated finger or hand was hopelessly lost, but due to evolving microsurgical techniques in the 1970s, successful replantation surgery is now possible in many cases [32].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree