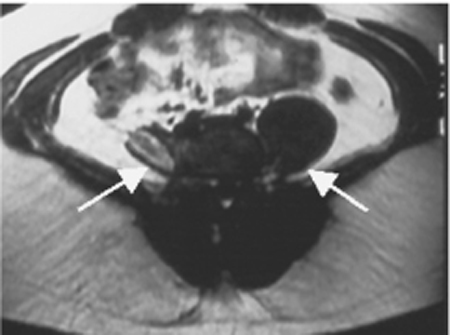

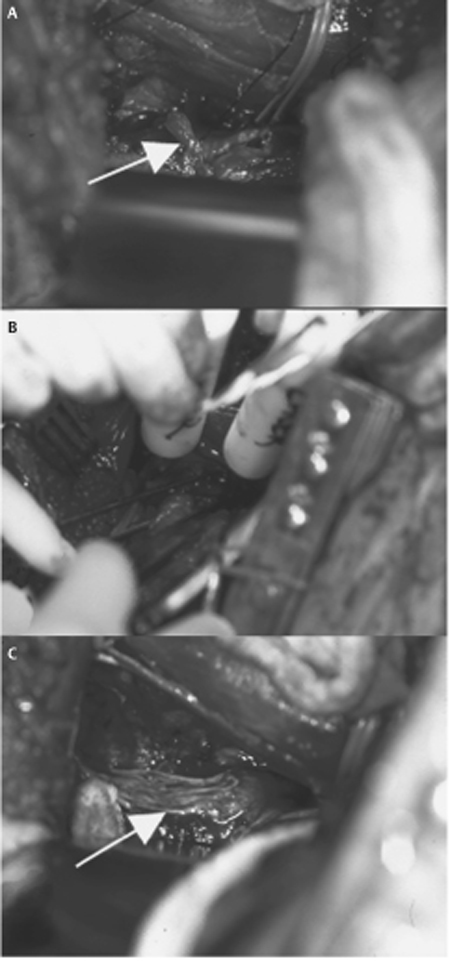

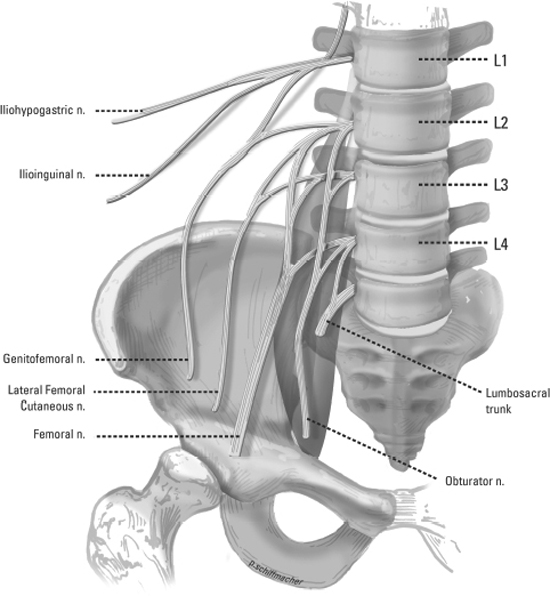

54 Lumbar Plexus Injury A 25-year-old man presented to the neurosurgery clinic for evaluation 2 months after a stab wound to the back. When initially evaluated in a local emergency room, the wound was simply irrigated and then sutured closed. He noted right leg weakness and numbness immediately after the incident but these findings were apparently not evaluated in the emergency department. In the neurosurgery clinic he was found to have profound right lower extremity weakness in the iliopsoas, quadriceps, and thigh adductors, with sensory loss over the anteromedial thigh and medial lower leg. An electrodiagnostic study showed chronic denervational changes in the distribution of the right femoral and obturator nerves, with no evidence of reinnervation. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed right psoas atrophy and a tract along the path of the knife with T2 hyperintensity in the area of the lumbar plexus (Fig. 54–1). He was taken to the operating room for a retroperitoneal exploration of the right lumbar plexus. Intraoperatively, the lumbar plexus elements that formed the femoral and obturator nerves were found to be functionally transected, with no transmission of nerve action potentials (NAPs) across the injury site. They were repaired with multiple sural nerve cable grafts (Fig. 54–2). The patient tolerated the procedure well and was discharged without complication. Postdischarge he returned for short-term wound care and analgesic medication but was ultimately lost to follow-up. Figure 54–1 T2-weighted axial magnetic resonance image from the described patient. Arrows delineate the psoas muscles. Note the atrophied right psoas muscle with T2 hyperintensity within the psoas representing the knife tract. Lumbar plexus injury The lumbar plexus is formed in the retroperitoneal space within the anterior and posterior masses of the psoas muscle. It receives innervation primarily from the ventral rami of L1, L2, L3, and L4, and commonly from T12. L4 contributes, via the lumbosacral trunk, to the sacral plexus as well. The branches of the lumbar plexus include the iliohypogastric, ilioinguinal, genitofemoral, obturator, lateral femoral cutaneous, and femoral nerves (Fig. 54–3). The nerves are formed in the following manner. The L1 spinal nerve splits into upper and lower branches. In some individuals, the L1 nerve receives a branch from T12 prior to this division. The upper branch divides into the iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves. The lower branch combines with a branch from L2 to form the genitofemoral nerve. The remaining L2 and the L3 and L4 spinal nerves divide into anterior and posterior divisions. The anterior divisions form the obturator nerve. The posterior divisions of L2 and L3 then divide further with distal branches uniting to form the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve. The remaining distal branches from L2 and L3 unite with the posterior branch of L4 to form the femoral nerve. For a detailed description of the anatomy of the iliohypogastric, ilioinguinal, obturator, lateral femoral cutaneous, and femoral nerves, please refer to Chapters 35 to 39. The genitofemoral nerve (L1, L2) has a great deal of variability in its course, divisions, and distribution of innervation. Most commonly, it divides into genital and femoral branches superior to the inguinal ligament. The genital branch enters the inguinal canal and innervates the cremaster muscle and skin of the scrotum and adjacent thigh in men. It supplies the skin of the mons pubis and labia majora in women. The femoral branch proceeds lateral to the femoral artery in the femoral sheath to supply the skin over the upper part of the femoral triangle. Figure 54–2 Operative photographs via a retroperitoneal approach demonstrating the injury to the lumbar plexus elements that comprise the femoral and obturator nerves. For reference, the psoas muscle is visualized at the superior aspect of the images. (A) After external neurolysis, preserved nerve is held within the vessel loop. The arrow points to the injury site with the transected nerve within scar. (B) Nerve action potential testing. (C) After repair with multiple sural nerve cable grafts (arrow at graft site). Due to its deep location and overlying protective anatomy, injuries to the lumbar plexus are rare. When injuries do occur they are most commonly iatrogenic or traumatic in origin. Iatrogenic causes are most often surgical in nature. Routine procedures within multiple specialties including general surgery, vascular surgery, gynecology, urology, orthopedics, neurosurgery, and interventional radiology may injure the lumbar plexus. Injuries have been described after laparoscopic and open herniorrhaphy, appendectomy, and prostatectomy. Obstetric and gynecologic procedures have been associated with nerve injury due to direct surgical trauma, suture entrapment, retractor placement, and patient positioning. Spine surgery, via iliac crest bone graft removal, anterior approaches to the lumbar spine and compression during positioning, as well as total hip arthroplasty are additional sources of injury commonly cited. Vascular procedures including aortofemoral bypass and cannulation of the femoral artery for angiography cause direct injury or secondary injury due to hematoma. The lumbar plexus is subject to damage via high impact blunt trauma and penetrating injuries such as stab wounds and gunshot wounds. Avulsions of lumbar nerve roots have been described after motor vehicle collisions, usually with severe pelvic fractures that involve sacroiliac dissociation. Pelvic fractures and other blunt trauma injuries can cause injury to the lumbar plexus and its branches distal to the roots as well. More detailed description of injury to the iliohypogastric, ilioinguinal, obturator, lateral femoral cutaneous, and femoral nerves can be found in Chapters 35 to 39. Genitofemoral nerve injury often causes chronic pain and paresthesias in the inguinal region. The symptoms often include hyperesthesias of the skin of the genital region and upper medial thigh as well. Patients may have inguinal canal or ring tenderness. Ambulatory activity and hip hyperextension may intensify symptoms while lying down, and hip flexion may alleviate symptoms. The differential diagnosis of lumbar plexus injury is broad with any disease process that causes weakness or numbness in the areas innervated by the lumbar plexus included in the differential. Proximal leg pain, numbness, or weakness can be secondary to a high lumbar disk herniation causing radiculopathy. Weakness can also be due to primary diseases of the muscle, including myopathy or myositis. Lumbosacral plexus neuropathy is a well-described idiopathic syndrome that can present with loss of muscle strength, asymmetrical hyporeflexia, and sensory disturbances not explained by a single nerve root or peripheral nerve. Such symptoms can occur in both diabetics and nondiabetics. Other causes of plexopathy include alcohol abuse, nutritional deficiency, vasculitis from connective tissue disorders, compression from hematomas, and radiation treatment. All of the symptoms described can also be found secondary to oncological disease, whether due to compression or direct invasion of the plexus or nerve. Isolated groin pain can be caused by injury to branches of the lumbar plexus as well as groin and inguinal region hernias. In all cases the diagnostic tests described should help to narrow the differential and guide treatment.

Case Presentation

Case Presentation

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

Anatomy

Anatomy

Characteristic Clinical Presentation

Characteristic Clinical Presentation

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree