42 Microendoscopic Anatomy of the Craniocervical Junction

Alberto Carlos Capel Cardoso, Roger S. Brock, Carolina Martins, Luiz Felipe de Alencastro, and Albert L. Rhoton, Jr.

Introduction

Introduction

The craniocervical junction (CVI) is a complex transition between the skull and the upper cervical spine (Fig. 42.1). It comprises the basiocciput, the atlas, and the axis, forming a funnel that provides stability and motion.1,2 It is a mobile junction responsible for more than a half of spinal axial rotation.3,4

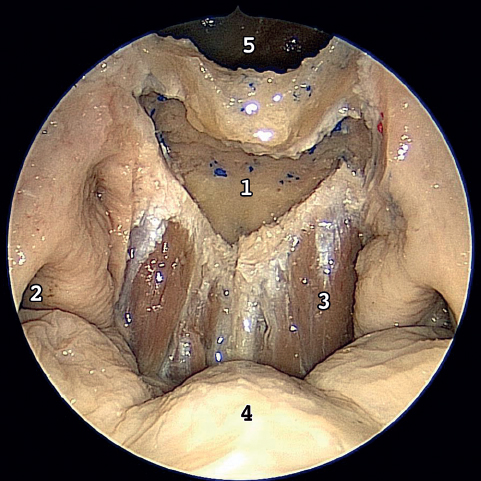

The craniocervical junction is located immediately behind the nasopharynx, which can be directly accessed transnasally (Figs. 42.2, 42.3, and 42.4).

An understanding of the bony configuration, joint articulations, ligamentous attachments, and vascular supply is necessary when attempting to reach this unique region through an anterior endoscopic approach.

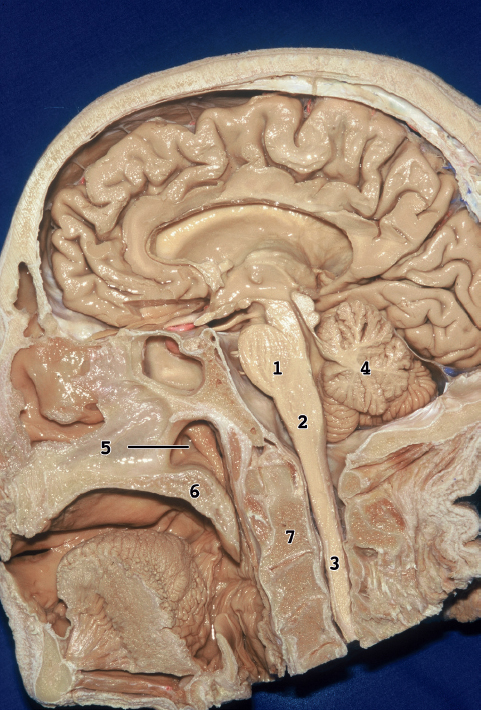

Fig. 42.1 Medial surface of the head. 1, pons; 2, medulla; 3, spinal cord; 4, cerebellum; 5, eustachian tube; 6, soft palate; 7, axis.

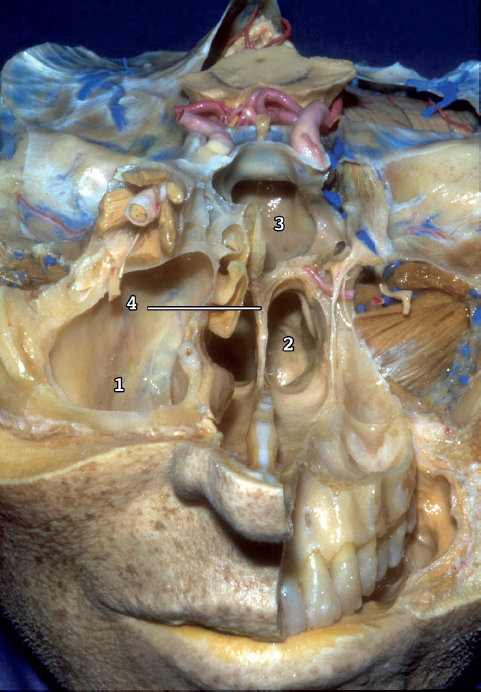

Fig. 42.2 Nasal pathway to the clivus. Dissection shows the structures that form the lateral limit of the transnasal route to the clivus. 1, maxillary sinus; 2, posterior nasopharyngeal wall; 3, sphenoid sinus; 4, vomer.

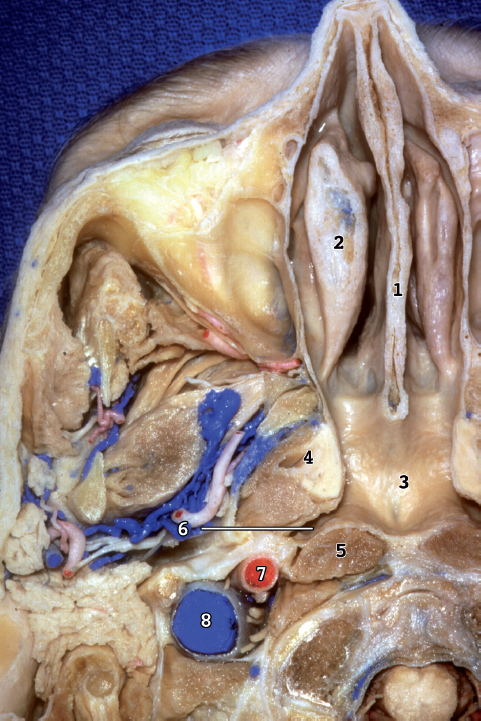

Fig. 42.3 Inferior view of an axial section of the skull base. 1, nasal septum; 2, middle concha; 3, posterior nasopharyngeal wall, which is separated from the lower clivus by the longus capitis muscle and the nasopharyngeal space; 4, eustachian tube; 5, longus capitis muscle; 6, pharyngeal recess (fossa of Rosenmüller), which projects laterally from the posterolateral corner of the nasopharynx with its lateral apex facing the internal carotid artery laterally and the foramen lacerum above; 7, carotid artery; 8, jugular vein.

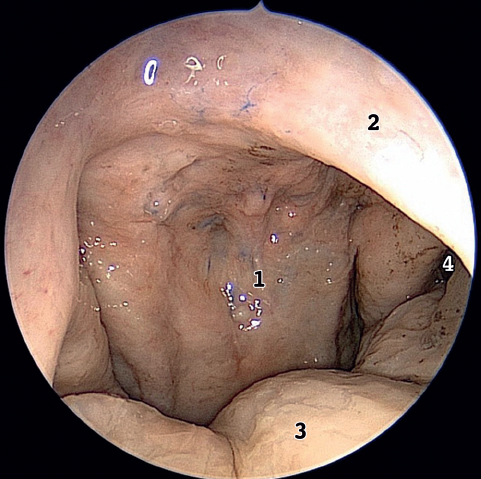

Fig. 42.4 View of the nasal cavity. 1, posterior nasopharyngeal wall; 2, nasal septum; 3, soft palate; 4, eustachian tube.

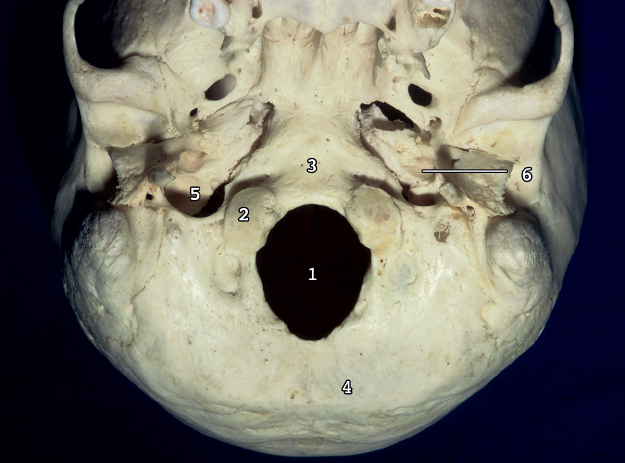

Fig. 42.5 Occipital one and foramen magnum, inferior view. The occipital bone surrounds the ovalshaped foramen magnum, which is wider posteriorly than anteriorly. The occipital bone is divided into a basal (clival) part situated in front of the foramen magnum; a paired condylar part located lateral to the foramen magnum; and a squamosal part located above and behind the foramen magnum. 1, foramen magnum; 2, occipital condyle; 3, clivus; 4, squamous part of the occipital bone; 5, jugular foramen; 6, carotid canal.

Bone Elements

Bone Elements

Occipital Bone

The occipital bone can be divided into a basal part situated in front of the foramen magnum, a squamosal part located above and behind the foramen magnum, and paired condylar parts located lateral to the foramen magnum (Figs. 42.5, 42.6, 42.7, and 42.8).

The Atlas

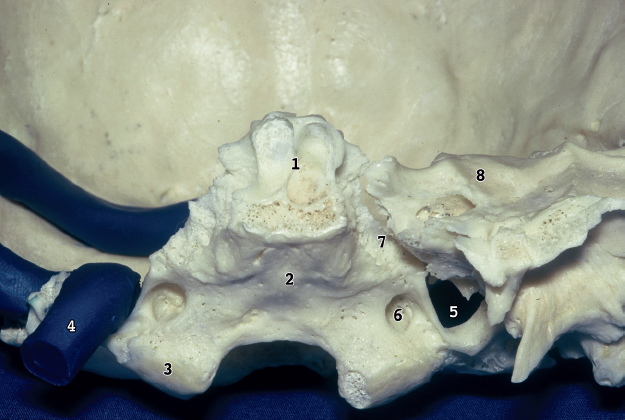

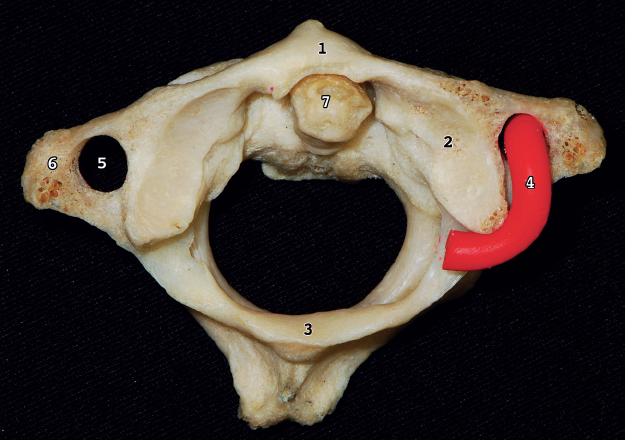

The atlas, the first cervical vertebra, differs from the other cervical vertebrae by being ring shaped and by lacking a vertebra body and a spinous process. It consists of two thick lateral masses connected in front by a short anterior arch and behind by a longer curved posterior arch. The position of the usual vertebral body is occupied by the odontoid process of the axis (Fig. 42.9). The upper surface of each lateral mass has an oval concave facet that articulates with the occipital condyle. The inferior surface of each lateral mass has a circular slightly concave facet that articulates with the superior articular facet of the axis (Fig. 42.10).

Fig. 42.6 Superior view of the occipital bone. 1, foramen magnum; 2, clivus, which is separated on each side from the petrous part of the temporal bone by the petroclival fissure; 3, jugular process of the occipital bone, which extends laterally from the posterior half of the condyle and articulates with the jugular surface of the temporal bone; 4, jugular foramen, which is bordered posteriorly by the jugular process of the occipital bone and anteriorly by the jugular fossa of the petrous temporal bone; 5, squamous part of the occipital bone; 6, sulcus of the sigmoid sinus, which crosses the superior surface of the jugular process; 7, temporal fossa.

Fig. 42.7 Anterior view of the occipital bone. 1, sphenoid sinus; 2, pharyngeal tubercle, which gives attachment to the fibrous raphe of the pharynx; 3, occipital condyle; 4, jugular vein; 5, jugular foramen; 6, hypoglossal canal, which is situated above the condyle; 7, petroclival fissure; 8, temporal bone.

The Axis

The axis is the second cervical vertebra. It forms a pivot for the atlas and the head to rotate. The axis is distinguished by the odontoid process (dens), which projects upward from the body. The dens and body are flanked by a pair of large oval facets that extend laterally from the body and articulate with the inferior facets of the atlas. The transverse process of the axis is small (Fig. 42.11).

Fig. 42.8 Anterior view. The nasal septum has been removed. 1, clivus; 2, eustachian tube; 3, longus capitis muscle; 4, soft palate; 5, sphenoid sinus.

Ligamentous Anatomy

Ligamentous Anatomy

The special arrangements of the craniocervical junction ligaments are remarkable, allowing a complex motion and provide stability.5

The cruciform ligament and alar ligament are the most important for CVJ stability.

Cruciform Ligament

The cruciform ligament has transverse and vertical parts that form a cross behind the dens. The cranial extension of the vertical part is attached to the upper surface of the clivus between the apical ligament of the dens and the tectorial membrane. The lower band is attached to the posterior surface of the body of the axis.

The transverse part, called the transverse ligament, is one of the most important ligaments of the body. It is a thick strong band that arches across the ring of the atlas. The neck of the dens is constricted where it is embraced posteriorly by the transverse ligament (Figs. 42.12, 42.13, and 42.14).

The biomechanical role of the cruciform ligament is to limit the anterior movement of the atlas on the axis, preventing anterior translation and flexion. Disruption of these ligamentous structures destabilizes the craniocervical junction.6

Alar Ligaments

The alar ligaments are two strong bands that arise on each side of the upper part of the dens and extend obliquely superolateral to attach to the medial surfaces of the occipital (Figs. 42.14, 42.15, and 42.16). Their function is to limit axial rotation between the atlas and the skull.

Fig. 42.9 Superior view of the atlas and the axis. The atlas consists of two thick lateral masses situated at the anteromedial part of the ring, which are connected in front by a short anterior arch and posteriorly by a longer curved posterior arch. 1, anterior arch of the atlas; 2, superior articular facet is an oval, concave facet that articulates with the occipital condyle; 3, posterior arch of the atlas; 4, vertebral artery (VA); 5, transverse foramina; 6, transverse process; 7, dens of the axis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree