Adverse effects of anticholinergic medications include both peripheral antimuscarinic side effects (e.g., dry mouth, impaired visual accommodation, urinary retention, constipation, tachycardia, and impaired sweating) and central effects (e.g., sedation, dysphoria, memory difficulties, confusion, and hallucinations).

(4) Dopamine receptor agonists directly stimulate dopamine receptors. The current commercially available oral dopamine agonists used for the treatment of PD in the United States are pramipexole (Mirapex) and ropinirole (Requip). Once-daily extended-release formulations are available for both pramipexole and ropinirole. Rotigotine (Neupro) is a transdermally delivered dopamine agonist, and apomorphine (Apokyn) is administered subcutaneously with a rapid onset of action but very short duration of benefit (60 to 90 minutes). The long-acting ergot derivatives bromocriptine and cabergoline are rarely used for the treatment of PD. Their use in North America has been largely restricted to the treatment of hyperprolactinemia.

Dopamine receptor agonists may relieve all of the cardinal manifestations of PD. Despite the theoretical advantages over levodopa by acting directly on striatal dopamine receptors while circumventing the degenerating dopaminergic neurons, dopamine agonists are less effective than levodopa, yielding a lower risk of dyskinesia and motor fluctuation compared with it, and have an extensive list of potential side effects. Agonists can be used both as monotherapy and as adjuncts to levodopa. To minimize side effects, the dosage of a dopamine agonist should be increased gradually until the desired effect is obtained. Table 45.1 shows common dosages for different antiparkinsonian drugs. Currently, apomorphine can only be administered subcutaneously as a rescue treatment for intractable and disabling wearing off, although it is available as a subcutaneous infusion therapy in Europe. Apomorphine titration in the clinic or under the supervision of a nurse at home to monitor for emesis and orthostatic hypotension is required to determine the correct dose of the drug while the patient is pretreated with an antiemetic, such as domperidone or trimethobenzamide.

Dopaminergic adverse effects of dopamine agonists include nausea, vomiting, orthostatic hypotension, excessive daytime sleepiness, and psychiatric manifestations including visual hallucinations and impulse-control disorders. Elderly and cognitively impaired patients are more prone to psychiatric side effects. Impulse-control disorders (excessive shopping, compulsive gambling, and hypersexuality, among others) may develop even after 20 months have elapsed after the onset of therapy, which demands regular monitoring. Also in the long term, dopamine agonists can cause leg edema and livedo reticularis. Older ergot-derived dopamine agonists such as bromocriptine and cabergoline in rare instances cause pulmonary and retroperitoneal fibrosis, cardiac valvulopathy, vasospasm, and erythromelalgia and can exacerbate angina and peptic ulcer disease.

(5) Levodopa is the most effective antiparkinsonian medication (![]() Video 45.1). It is mainly absorbed in the proximal small intestine by a carrier-mediated process for neutral amino acids and is similarly transported across the blood–brain barrier. Once in the brain, it is converted to dopamine by the enzyme aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase. Levodopa is administered in combination with a peripheral dopa decarboxylase inhibitor (carbidopa in North America or benserazide in Europe) which markedly reduces the required total daily dose of levodopa and minimizes the gastrointestinal side effects and hypotension caused by peripheral conversion of levodopa to dopamine.

Video 45.1). It is mainly absorbed in the proximal small intestine by a carrier-mediated process for neutral amino acids and is similarly transported across the blood–brain barrier. Once in the brain, it is converted to dopamine by the enzyme aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase. Levodopa is administered in combination with a peripheral dopa decarboxylase inhibitor (carbidopa in North America or benserazide in Europe) which markedly reduces the required total daily dose of levodopa and minimizes the gastrointestinal side effects and hypotension caused by peripheral conversion of levodopa to dopamine.

Currently available preparations of carbidopa–levodopa include immediate-release carbidopa–levodopa (Sinemet), an orally disintegrating tablet (Parcopa), a controlled-release preparation (Sinemet CR), an extended-release capsule formulation (Rytary), and an enteral suspension (Duopa) for continuous administration through a portable infusion pump. A minimum of 75 mg/day of carbidopa is required for appropriate peripheral decarboxylation. While both controlled- and extended-release preparations are less bioavailable than immediate-release carbidopa–levodopa, the erratic pharmacokinetics of the CR form generally limits its use to nighttime administration for the treatment of nocturnal or early-morning reemergence of parkinsonian symptoms. The ER capsule formulation comprises different types of beads including immediate-release and extended-release beads combined in a specific ratio, designed to allow for an onset as rapid that of IR, but allowing for a longer duration of benefit.

Levodopa generally relieves all of the cardinal signs of PD—bradykinesia, tremor, and rigidity. It should be the first-line treatment in any patient older than 70 years of age or in younger individuals with moderate-to-severe disability. Unlike the core deficits of tremor, bradykinesia, and rigidity, axial deficits, such as impaired postural reflexes, hypophonia, and dysphagia, are less reliably improved. A lack of response to levodopa may suggest a diagnosis of one of the atypical parkinsonisms, but an adequate trial with doses up to 1,500 mg of levodopa should be tried before considering anyone a nonresponder. Treatment with carbidopa–levodopa usually is initiated using 25 per 100 immediate-release tablets titrating slowly upward to minimize any acute side effects.

As the disease progresses, patients may develop motor complications in the form of motor fluctuations with wearing off toward the end of a dose cycle (reemergence of parkinsonian deficits or appearance of end-of-dose or early-morning dystonia) or choreic or choreathetoid movements (dyskinesia). Wearing off can be improved by decreasing the interdose interval of levodopa, increasing the individual levodopa doses, changing to the ER capsule formulation, adding a catechol-o-methyl-transferase (COMT) or MAO-B inhibitor, or considering apomorphine subcutaneous injections. Choreic movements of the upper body, predominantly head and neck, are often indicative of peak-dose dyskinesia and require lowering the levodopa dose, increasing the interdose interval, or adding amantadine. Choreic movements predominantly of the lower body, especially legs, feet, and pelvis, may occur at the beginning of or at the end of a dose cycle of levodopa and are referred to as diphasic dyskinesia. Unlike peak-dose dyskinesias, diphasic dyskinesias are treated by increasing the dose of levodopa or decreasing the interdose interval. In general, motor complications, particularly dyskinesia, begin after 2 to 10 years of levodopa therapy. Younger patients are more prone to dyskinesia and motor fluctuations earlier in the course of the disease. When medication adjustments do not improve these motor complications, deep brain stimulation (DBS) of the subthalamic nucleus (STN) or internal segment of the globus pallidus (GPi) may be considered (see section A.3 under Hypokinetic Movement Disorders, below). Alternatively, prominent motor fluctuations can also be improved by implanting a percutaneous gastrojejunostomy tube and administering a continuous infusion of carbidopa–levodopa enteral suspension via a portable infusion pump.

Adverse effects of levodopa can be classified into acute and chronic. In the short term, nausea, vomiting, and hypotension-related lightheadedness can be addressed by adding extra carbidopa (Lodosyn), 25 to 75 mg three times per day, to enhance the peripheral decarboxylation and minimize bioavailability of dopamine outside the brain, where this is typically toxic. Another option is to use a peripheral dopamine receptor blocker such as domperidone. Due to the possibility of ventricular arrhythmia and QT prolongation, doses of domperidone should be kept ideally at 10 mg three times a day, and raised only if needed to 20 mg three times per day. Domperidone is not currently available in the United States but can be readily obtained from Canadian online pharmacies.

In the long term, patients may develop behavioral complications in the form of psychosis, paranoia, sexual preoccupation, impulse-control disorder, mania, or agitation. Visual hallucinations can be quite vivid in the form of people or animals. The psychosis is usually dose-dependent and typically lessens with medication reduction, although at the expense of deterioration of motor function. Quetiapine (Seroquel) or clozapine (Clozaril) may be considered in these cases, as the only antipsychotics safe to use in PD. Pimavanserin (Nuplazid), a selective serotonin 5-HT2A inverse agonist, is the first FDA-approved medication for psychosis associated with PD. Reports of accelerated melanoma growth in PD patients taking levodopa have been published. However, melanoma seems to be more prevalent among PD patients regardless of their exposure to levodopa or other PD drugs.

(6) COMT inhibitors are used as adjuncts to levodopa. By blocking the peripheral conversion of levodopa to 3-o-methyldopa, COMT inhibitors increase the bioavailability of levodopa. Two COMT inhibitors are available—tolcapone (Tasmar) and entacapone (Comtan). A combination carbidopa–levodopa–entacapone preparation (Stalevo) is also available. Tolcapone is used in doses of 100 to 200 mg three times a day, and entacapone 200 mg is given with each dose of levodopa up to 2,000 mg/day. If tolcapone is used, liver function tests should be monitored periodically at least for the first 6 months because of earlier reports of rare cases of tolcapone-induced liver failure, some fatal. Side effects of COMT inhibitors are related to increased bioavailability of levodopa. In addition, diarrhea and a brownish-orange discoloration of the urine may occur.

(7) Visual hallucinations and psychosis are adverse effects that can occur in association with any antiparkinsonian medication. Any potential triggering event, such as infections or metabolic derangements, should be actively sought and treated, if present. Otherwise, decreasing or discontinuing the dose of dopaminergic medications is warranted, in the following order if hallucinations persist: anticholinergics, amantadine, selegiline/rasagiline, and dopamine agonists. If worsening of motor symptoms make such a reduction impossible, the judicious use of one of the safe atypical antipsychotics quetiapine or clozapine, or an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, such as rivastigmine, may be necessary. Clozapine (Clozaril) is typically started at a dose of 12.5 mg at bedtime, and increased slowly to benefit. Because 1% to 2% of patients taking clozapine may experience agranulocytosis, patients should be monitored with weekly blood counts. Quetiapine (Seroquel) is effective in the management of dopaminergic-induced psychosis at doses of 12.5 mg to 300 at night without worsening parkinsonism. Pimavanserin (Nuplazid) can also be used at a dose of 34 mg daily.

(8) Constipation is a common problem among PD patients. Management should include dietary modifications, increasing fluid and fiber intake, exercise, and minimizing or eliminating the use of anticholinergic medications. Psyllium (Metamucil), polyethylene glycol (Miralax), sorbitol and lactulose can be helpful, as well as agents that stimulate intestinal motility such as bisacodyl (Dulcolax). Some patients may need enemas.

(9) Other potential problems of patients with PD include nocturia, urinary urgency and frequency, erectile dysfunction, dysphagia, orthostatic hypotension, and sleep problems (see Chapters 7, 9, 18, and 32). Depression requires special mention as it affects about 50% of patients with PD and may respond to antidepressant medications such as SSRIs and SNRIs, given the involvement of serotonin but importantly of norepinephrine in PD.

3. Surgical treatment of PD. The neurosurgical treatment of PD has progressed from destructive and lesional procedures to focused and targeted brain stimulation. The success of surgical treatment depends on a careful selection of the appropriate candidates. First, only patients with idiopathic PD should be considered. Patients with advanced disease, poor response to levodopa, dementia, uncontrolled depression, uncontrolled hallucinations, and unstable medical problems are unlikely to benefit from these procedures. Surgical candidates should undergo a presurgical neuropsychological evaluation to rule out substantial cognitive dysfunction. The effects of DBS typically mirror the benefits of levodopa, however, with the benefit of reducing motor fluctuations and off time, as well as decreasing dyskinesia. The two main targets for DBS in PD, the subthalamic nucleus (STN) and internal segment of the globus pallidus (GPi), appear to give similar outcomes, although individual patient factors and surgeon expertise may be important.

a. Thalamic DBS is effective at reducing tremor in PD, and although the benefit is sustained, Vim DBS does not address bradykinesia or other PD symptoms, which invariably progress over time.

b. STN DBS yields excellent antiparkinsonian benefit and allows for greater medication reduction than GPi stimulation.

c. Pallidal DBS, targeting the posteroventral GPi, is more effective at reducing dyskinesia and secondary dystonia. Although there is some suggestion that GPi DBS is “safer” from a neurocognitive standpoint, leading some to suggest this target for cognitively impaired patients who are otherwise good candidates, controlled clinical trials have not demonstrated significant cognitive differences in outcomes between the two targets.

B. Atypical parkinsonism are a group of rare degenerative conditions within the akinetic-rigid syndrome to which PD belongs.

1. Multiple system atrophy (MSA) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease characterized by a combination of parkinsonism, cerebellar dysfunction, and autonomic failure. The nomenclature MSA-P and MSA-C are used when parkinsonian or cerebellar features predominate, respectively. The parkinsonism tends to be tremorless. Clinical features that suggest the diagnosis are hyperreflexia or other corticospinal signs, severe early orthostatic hypotension and/or urinary incontinence, atypical levodopa-induced dyskinesias (affecting face [sardonic grin] and feet), Pisa syndrome (lateral truncal deviation), and inspiratory stridor.

a. Levodopa may provide transient improvement of parkinsonian sympoms albeit rarely sustained beyond 1 year. Other dopaminergic drugs are not indicated.

b. Orthostatic hypotension may be the greatest source of disability and can be worsened by levodopa. Nonpharmacologic measures include liberalizing salt and water intake, using waist or thigh-high compressive leg stockings during the day, and raising the head of the bed 8 inches (20 cm) at night to minimize supine hypertension and excessive nocturnal diuresis. Patients should be careful rising from the sitting or supine positions and should avoid heavy meals. When pharmacotherapy is required, the peripheral α-1-adrenergic receptor agonist midodrine (ProAmatine) may be used, starting at 2.5 mg three times a day, increasing by 2.5-mg weekly increments up to a maximum of 10 mg three times a day. When midodrine is insufficient, treatment with the mineralocorticoid fludrocortisone (Florinef) may be added at doses of 0.1 to 0.3 mg/day, as needed. The norepinephrine precursor droxidopa (Northera), starting at 100 mg and increasing up to 600 mg three times a day, as tolerated, has also been shown to improve postural lightheadedness in patients with orthostatic hypotension. Other potentially useful drugs are methylphenidate, pyridostigmine, erythropoietin, ergots, and desmopressin.

c. Urinary frequency or incontinence should be evaluated with the assistance of an urologist. Treatments such as oxybutynin (Ditropan), solifenacin (Vesicare), tolterodine (Detrol), darifenacin (Enablex), or trospium chloride (Sanctura) for a spastic bladder or bethanechol (Urecholine) for a hypotonic bladder may provide relief. Some patients need intermittent or continuous catheterization. Sildefanil (Viagra), tadalafil (Cialis), and vardenafil (Levitra) may be useful for management of erectile dysfunction.

d. Dysarthria and dysphagia may benefit from evaluation by a speech therapist. Some patients with severe dysphagia need percutaneous gastrostomy. Gait difficulties and instability may necessitate use of supportive devices and physical therapy. Patients with MSA and inspiratory stridor should undergo a sleep study to determine whether concurrent obstructive sleep apnea requires treatment.

2. Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) is an atypical parkinsonism characterized by early postural instability and falls, disproportionate neck rigidity (sometimes with retrocollis), facial dystonia, supranuclear vertical gaze abnormalities, pseudobulbar affect, subcortical frontal dementia, and apathy.

a. Management of PSP is extremely limited. Antiparkinsonian medications are rarely helpful, although a trial of levodopa is prudent.

b. Symptomatic palliative therapies for PSP include management of dysarthria and dysphagia with the assistance of a speech therapist and may include the use of a gastrostomy tube among other measures. Because of the significantly decreased blinking rate, patients with PSP are at increased risk of keratitis and should use artificial tears. Blepharospasm and neck dystonia can be managed with botulinum toxin injections. Depression can be managed with serotonergic and/or noradrenergic antidepressants and emotional incontinence (pseudobulbar affect) with dextromethorphan/quinidine (Nuedexta). Dystonia may benefit from amantadine. Gait instability can be managed with physical therapy and supportive devices.

HYPERKINETIC MOVEMENT DISORDERS

A. Chorea is an involuntary movement disorder characterized by irregular, dance-like jerky movements occurring within or between body parts in a random sequence. It can result from a variety of disorders of the basal ganglia.

1. Huntington’s disease (HD) is an autosomal-dominant degenerative brain disorder characterized by the insidious development of motor, cognitive, and psychiatric symptoms progressing toward death on average of about 20 years after onset of symptoms. The underlying genetic defect is the expansion of a CAG trinucleotide repeat of the htt gene, the product of which is a protein called huntingtin. Symptomatic treatment is directed at the major clinical features of the disease.

a. Choreiform movements can be reliably controlled with neuroleptics that have potent postsynaptic dopamine blocking effects such as haloperidol. Benzodiazepines such as lorazepam and clonazepam may also decrease chorea. Tetrabenazine (Xenazine), a reversible dopamine depleter and mild postsynaptic dopamine blocker, is effective in reducing chorea. Effective doses range from 12.5 to 50 mg three times a day.

b. Depression affects at least 30% to 50% of patients with HD. In HD patients, the suicide rate is four to eight times greater than in the general population. Depression can be managed with all standard agents used for the management of major depression. SSRIs typically are the drugs of choice for HD. Mirtazapine (Remeron) can be helpful in the care of HD patients with cachexia, anxiety, and insomnia because it can increase body weight and assist in sleep induction.

c. Irritability and aggressive behavior are common psychiatric manifestations in HD. First-line therapy for these symptoms is typically an SSRI or neuroleptic. Propranolol (Inderal), valproic acid (Depakote), and carbamazepine (Tegretol) are also potentially useful to treat aggressive behavior related to frustration and impatience.

d. Mania and hypomania can occur, although they may be difficult to distinguish from impulsivity and disinhibition associated with the dysexecutive syndrome common in HD. Approximately 10% of HD patients may exhibit hypomanic behavior. Therapeutic alternatives include valproic acid, lamotrigine (Lamictal), and carbamazepine, whereas lithium is less effective.

e. Psychosis has an estimated frequency of 3% to 25% among patients with HD and is more common among patients with early-onset disease. Antipsychotic medications such as risperidone (Risperdal) or olanzapine (Zyprexa) can be effective at reducing these symptoms, and can also help with chorea.

2. Other causes of chorea include neurodegenerative disorders (e.g., chorea-acanthocytosis, Wilson’s disease [WD], and dentatorubropallidoluysian atrophy), Sydenham’s chorea, systemic lupus erythematosus, hyperthyroidism, and drug-induced chorea (e.g., phenytoin, oral contraceptives, stimulants, or antiparkinsonian drugs). Regardless of the underlying cause, the movements can be improved with the use of neuroleptics. However, disease-specific treatments should be pursued as appropriate (e.g., warfarin in antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, penicillin in Sydenham’s chorea). The risk of tardive dyskinesia (TD) is uncertain when neuroleptics are used in the treatment of chorea.

3. NMDA-receptor antibody encephalitis is an autoimmune disorder associated with ovarian teratoma due to antibodies against the NMDA receptor. It is most common in young African-American women with choreoathetotic (dyskinetic) movements of the craniofacial region in the setting of “wakeful unresponsiveness,” particularly if preceded by psychotic features and seizures. Treatment includes first-line immunotherapy (steroids, intravenous immunoglobulin, plasmapheresis), second-line immunotherapy (rituximab, cyclophosphamide), and teratoma removal.

4. Hemiballismus is a severe form of chorea, with violent, flailing movements of the proximal aspect of the limbs on one side of the body. It is classically caused by lesions in the contralateral STN, but lesions outside the STN are more common. Non-ketotic hyperglycemia is the most common metabolic cause. Treatment includes supportive care, prevention of self-injury, and pharmacologic agents such as benzodiazepines, neuroleptics, and catecholamine-depleting agents (reserpine or tetrabenazine). Valproic acid and other gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-ergic drugs may be alternative therapeutic options. Surgical alternatives exist for patients who do not appropriately respond to medical therapy.

B. Tics are common movement disorders, affecting as many as 20% of children. They are brief, rapid, purposeless, repetitive movements involving one or more muscular groups. They are differentiated from other paroxysmal movement disorders by their partial voluntary control with suppressability when performing complex tasks, premonitory “urge,” and stereotypic appearance.

1. Tourette’s syndrome (TS) is a childhood-onset neuropsychiatric disorder characterized by motor and phonic tics. Tics wax and wane and tend to improve considerably during adulthood. Obsessive–compulsive behavior and attention deficit disorder (ADD) are comorbid conditions frequently associated with TS and may be more disabling than tics themselves.

a. Tics do not require treatment unless they are troublesome to the patient. The first step in treatment is education and reassurance. Cognitive behavioral therapy has emerged as an effective nonpharmacologic intervention. If further symptomatic improvement is needed, clonidine (Catapres) starting at 0.05 mg at bedtime and increased 0.05 mg every few days can be considered. The efficacy of clonidine for tic control is modest, however. Guanfacine (Tenex) starting at 0.5 to 1 mg at bedtime is another option that may be less sedating than clonidine.

Neuroleptics are the most efficacious agents for tic suppression. Haloperidol is probably the most commonly used neuroleptic for tics. Pimozide (Orap) was developed specifically for use in TS and may cause less sedation than haloperidol does. Other typical neuroleptics such as fluphenazine, trifluoperazine, and thiothixene can also be helpful. Atypical antipsychotics such as risperidone (Risperdal), ziprasidone (Geodon), aripripazole (Abilify), and olanzapine (Zyprexa) may be used. The necessary dosage can vary widely among patients and at different times for a given patient, given the fluctuating severity of the natural history of tics. Sedation and depression may be troublesome side effects, and the risk of QT interval prolongation should be noted. Although the risk of TD appears to be low among patients with TS, this potential long-term adverse effect must be discussed with patients and documented in the medical record. Tetrabenazine (Xenazine) is effective for tic suppression and is not linked with TD. Clonazepam (Klonopin) and baclofen may be helpful to some patients. Botulinum toxin injections may be helpful for some tics.

b. Management of obsessive–compulsive behavior associated with TS is identical to that of the purely psychiatric condition. SSRIs and clomipramine (Anafranil), may be used in this regard. The major adverse effects of clomipramine are sedation and anticholinergic effects.

c. ADD and other behavioral disorders of children may be difficult to control. Clonidine, tricyclic antidepressants, or selegiline may be effective. Use of central nervous system (CNS) stimulants such as methylphenidate (Ritalin) may ease ADD. Modafinil (Provigil) may be useful as well. The diverse behavioral abnormalities sometimes exhibited by children with TS not infrequently necessitate family counseling and other nonpharmacologic approaches.

C. Myoclonus is a shock-like, brief, involuntary movement caused by muscular contraction (positive myoclonus) or muscular inhibition (negative myoclonus). Myoclonus can originate from the cortex, subcortical areas, brainstem, or spinal cord. Common causes of myoclonus include metabolic derangements, such as renal and hepatic failure, epileptiform disorders, and neurodegenerative disorders.

1. Diagnosis should include a thorough history and physical examination plus blood glucose and electrolytes, drug and toxin screen, renal and hepatic function tests, brain imaging, and EEG. A search for inborn errors of metabolism and paraneoplastic antibodies may be indicated in some cases.

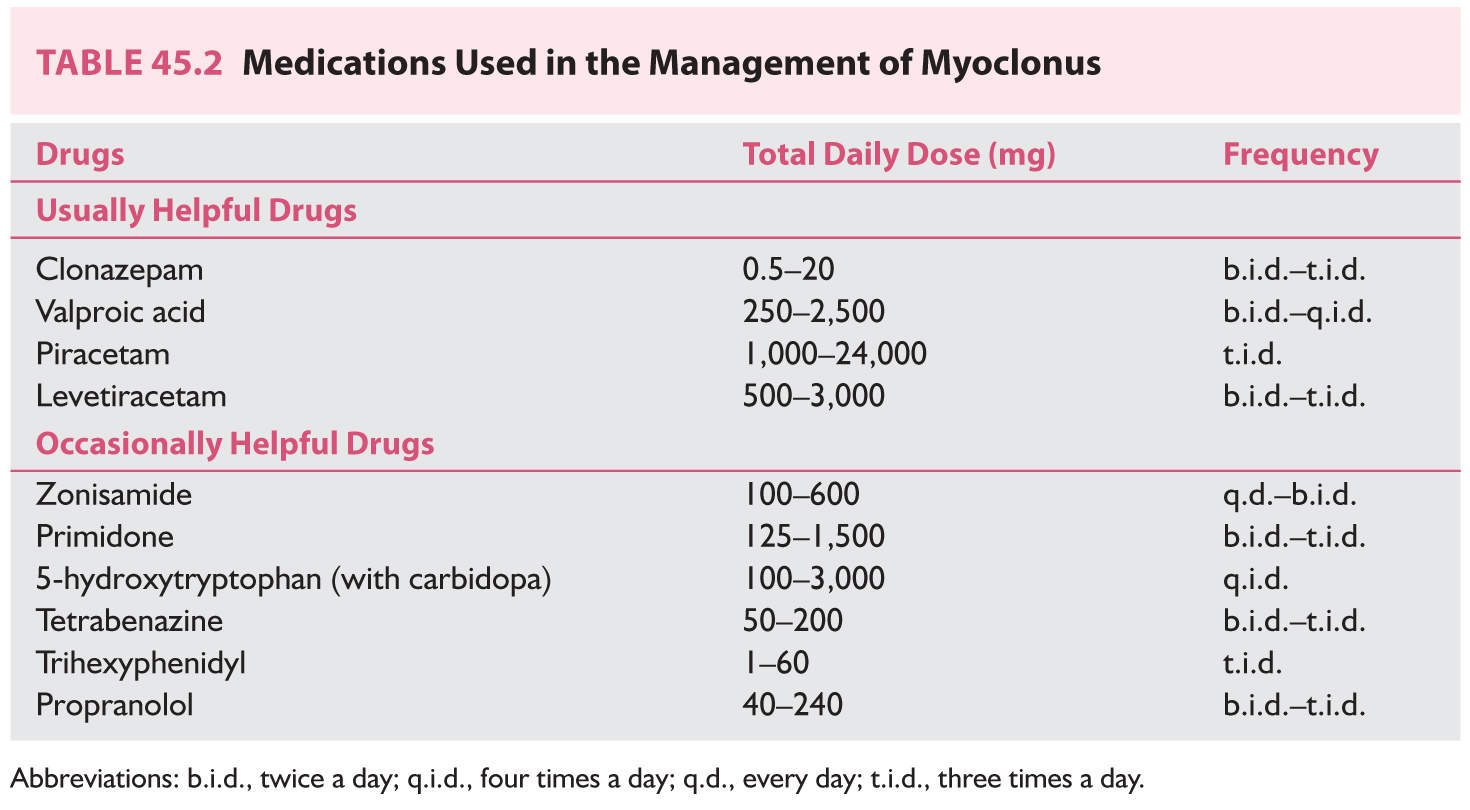

2. The ideal therapy for myoclonus is to manage the underlying condition. However, symptomatic treatment should be used if treatment is likely to make a significant functional impact (Table 45.2). Clonazepam at 2 to 6 mg/day, valproic acid (Depakote) 250 to 1,500 mg/day, levetiracetam (Keppra) 500 to 4,000 mg/day, and piracetam up to 24 g/day (not available in the United States) are first-line drugs for the management of myoclonus. Many patients need polytherapy to control myoclonus.

D. Tardive Dyskinesia is a generic term used to describe persistent involuntary movements that occur as a consequence of long-term treatment with dopamine receptor antagonists. Antipsychotics are the main causative group of medications, but antiemetics such as metoclopramide, prochlorperazine, and promethazine may also induce TD. The risk factors for development of classic TD include old age, female gender, mood disorder, and “organic” brain dysfunction. Classic TD usually consists of oral–buccal–lingual dyskinesia that may be associated with a variety of repetitive limb or trunk stereotyped movements.

1. The pathophysiologic mechanism of TD is not completely understood, but it is thought to be related to an increased number and affinity of postsynaptic D2 dopamine receptors in the striatum. The patient’s condition may initially improve after the offending agent is restarted or after the dosage is increased. Unfortunately, this is likely to perpetuate the problem.

2. The ideal management of TD would be prevention of this condition by avoiding unnecessary use of dopamine receptor antagonists and using the minimally effective dose. Anticholinergic medications can worsen classic TD.

a. Dopamine depleters such as reserpine or tetrabenazine have been among the most useful medications to treat TD. Dosages of reserpine usually are started at 0.10 to 0.25 mg three times a day and may be gradually increased to 3 to 5 mg/day. Reserpine may cause parkinsonism, depression, orthostatic hypotension, and peptic ulcer disease. Tetrabenazine can be started at 25 mg/day and gradually increased up to 150 mg/day in divided doses. The most common limiting side effects are sedation, depression, and parkinsonism.

b. Benzodiazepines may prove useful for patients with mild symptoms. Long-acting agents such as clonazepam (usually 1.5 to 3 mg/day) provide the most consistent relief of symptoms.

c. Branched-chain amino acids (Tarvil) have been shown to significantly decrease TD symptoms in males. It is used at a dose of 222 mg/kg three times a day.

d. Neuroleptics, used in the lowest possible dosages, may be necessary if symptoms markedly interfere with activities of daily living.

e. Tardive dystonia is a subtype of TD that typically affects younger people. It usually involves the neck and trunk muscles. Management of tardive dystonia differs from that of classic TD in that anticholinergics are potentially beneficial, and botulinum toxin can be used in focal or segmental forms. Dopamine depleters are also useful. GPi DBS may also be considered.

f. For many patients, combination therapy is most effective. The use of a benzodiazepine with either a dopamine depleter or a low dosage of an atypical neuroleptic may be necessary. Vitamin E might prevent further deterioration of TD, but it is not really clear if it can improve TD symptoms. The eventual rate of remission is approximately 60% and improvement is slow, taking as long as 2 years.

E. Dystonia is a syndrome of sustained muscle contraction causing abnormal repetitive movements, twisting, or abnormal postures. Numerous genetic forms of dystonia exist, and are typically designated as DYTn. Idiopathic dystonia can be generalized or restricted to a particular muscle group. With the exception of DYT3 (X-linked Lubag disease), patients with primary idiopathic dystonia have no gross or microscopic abnormalities. Secondary dystonia includes several inherited inborn errors of metabolism such as dopa-responsive dystonia (DRD or DYT5) and WD. Trauma, vascular disease, space-occupying lesions, drugs, and toxins are other causes of secondary dystonia.

1. DRD or DYT5 is an autosomal-dominant disorder caused by a mutation in the GTP cyclohydrolase I gene. It usually becomes apparent during childhood with a gait disorder, foot cramping, or toe walking. It can involve the trunk and arms and can be misdiagnosed as cerebral palsy. Patients with this form of dystonia have few symptoms after first awakening but the symptoms progress throughout the day. This disorder is exquisitely sensitive to small doses of levodopa (50 to 200 mg). A brief trial of levodopa for childhood-onset dystonia is frequently recommended to exclude DRD.

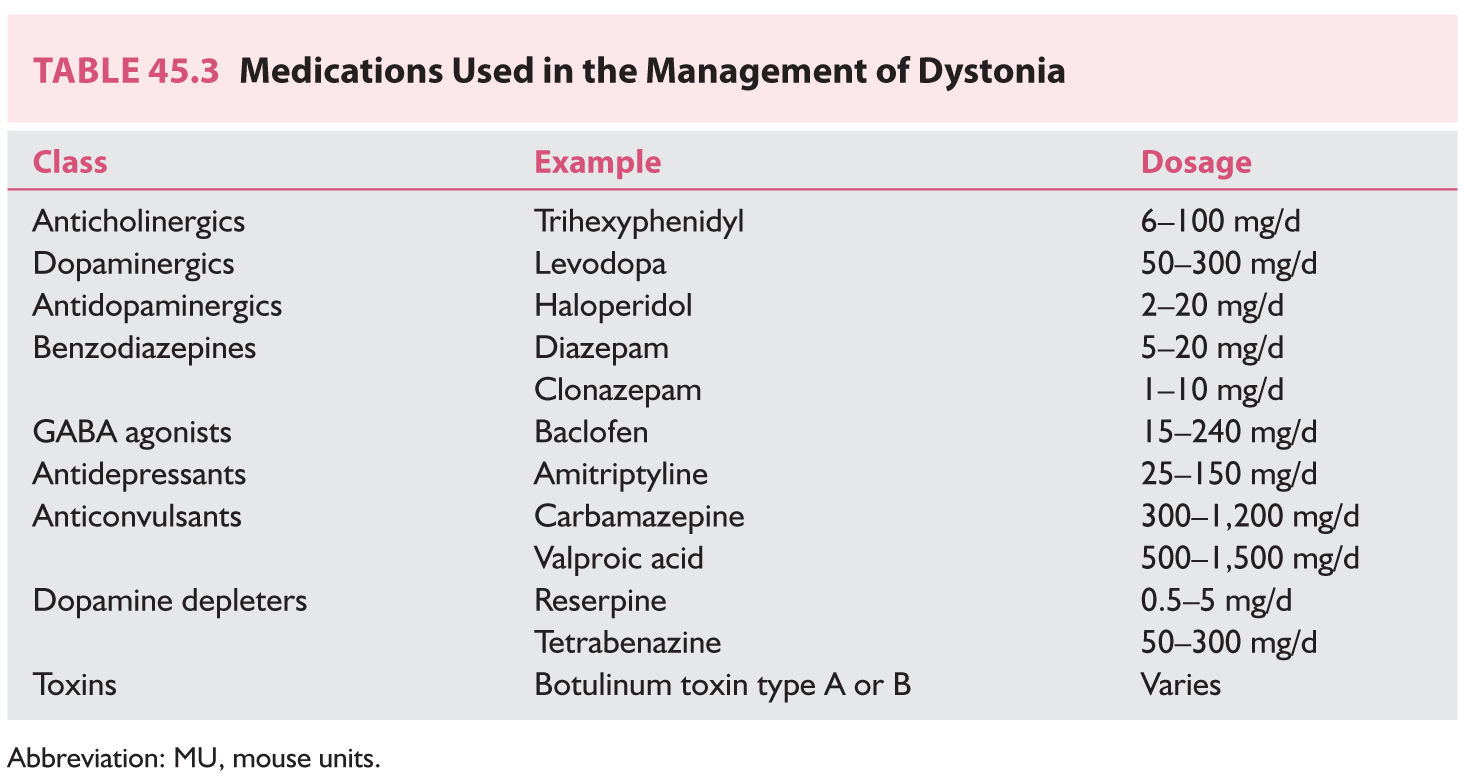

2. Medical management of dystonia of any cause can be attempted with the medications listed in Table 45.3. None of these medications provides complete relief of symptoms. Combinations of medications can be beneficial. Extremely high doses of anticholinergic drugs such as trihexyphenidyl have been reported to benefit more than 50% of patients in some trials (sometimes at doses greater than 100 mg/day). Therapy usually is started with 1 mg/day and increased 1 to 2 mg/week divided on a three times a day schedule until control of symptoms is achieved or intolerable adverse effects appear. The combination of a dopamine depleter such as reserpine, an anticholinergic, and a postsynaptic dopamine blocker may be beneficial to patients with severe dystonia. GPi DBS can be offered to patients to with pharmacologically intractable and disabling dystonia.

3. Injection of botulinum toxin is the first line of treatment of many patients with focal and segmental dystonia. There are seven botulinum toxin serotypes, but only types A and B are available in the United States—botulinum toxin type A -(onabotulinumtoxinA [Botox], abobotulinumtoxinA [Dysport], and incobotulinumtoxinA [Xeomin]) and botulinum toxin type B (rimabotulinumtoxinB [MyoBloc]). The toxin is injected directly into the affected muscle, producing reversible pharmacologic denervation. Injections usually are repeated at an average interval of 12 to 16 weeks. Potential side effects include excessive transient weakness of the injected and adjacent muscles, dry mouth, and local hematoma.

F. Tremor is probably the most common movement disorder. It is defined as a rhythmic oscillation around an axis of a given body part.

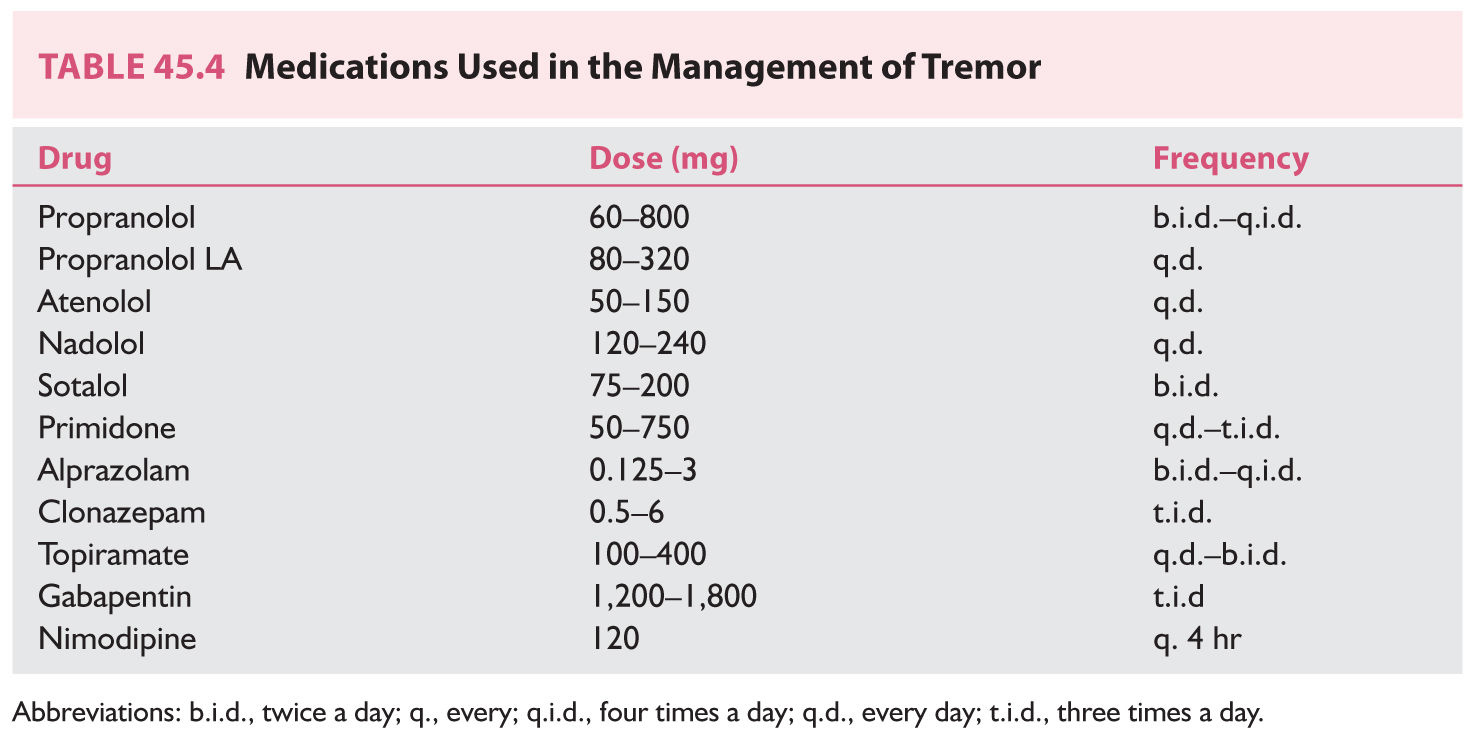

1. Essential tremor (ET) is a default diagnosis for a range of tremor disorders that predominantly include postural and kinetic tremor of the hands and, variably, head and vocal cords. A positive family history of tremor is common among ET patients. Tremor typically may improve with small amounts of alcohol. Generally, it is not possible to completely eliminate the tremor, and the goal of therapy should be to normalize activities of daily living. One-half to two-thirds of patients with ET benefit from pharmacologic therapy (Table 45.4). In some cases, the tremor may be quite refractory, and surgical treatment should be considered.

a. a-Adrenergic receptor antagonists are used most extensively to manage ET. The clinical response to β-blockers is variable and usually incomplete. These drugs reduce tremor amplitude but not tremor frequency and appear to be less effective in managing voice and head tremor. Nonselective β-blockers such as propranolol (Inderal) are preferred. Propranolol should be started at small doses (e.g., 10 mg three times a day) and titrated upward as needed. Doses larger than 320 mg/day usually do not confer additional benefit. Potential side effects of β-blockers include congestive heart failure, second- or third-degree atrioventricular block, worsening of obstructive lung disease, and masking of signs of hypoglycemia. The β-blockers can also cause fatigue, nausea, diarrhea, rash, erectile dysfunction, and depression. Nadolol (Corgard) is an option if propranolol causes CNS side effects, as this drug does not readily cross the blood–brain barrier. Atenolol (Tenormin), sotalol (Betapace), metoprolol (Lopressor), and timolol are potentially useful in the treatment of ET.

b. Primidone (Mysoline) may improve ET. The mechanism of action of primidone for management of tremor is unknown. Primidone decreases the amplitude of tremor but does not alter its frequency. Treatment usually is started at 25 mg at bedtime, and a response may begin at doses between 50 and 350 mg/day. Doses up to 750 mg/day divided three times a day may be required for benefits to appear. Side effects include vertigo, nausea, unsteadiness, and drowsiness.

c. Benzodiazepines may be used if the above drugs do not provide sufficient control of symptoms. Long-acting agents such as clonazepam can be used, but some patients may respond better to the use of a shorter-acting agent such as alprazolam (Xanax). Clonazepam at 1 to 3 mg/day can be very effective in orthostatic tremor. Potential adverse effects include sedation, ataxia, tolerance, and potential for abuse.

d. Botulinum toxin injections of limb tremor in ET may offer modest improvement of tremor that might be more cosmetic than functional as no improvement has been seen in functional scales. Transient weakness is the most common side effect.

e. Other drugs that may be considered for the management of ET are gabapentin (Neurontin), topiramate (Topamax), and zonisamide (Zonegran).

f. Surgery should be considered when activities of daily living are severely affected despite medical management. Stereotactic thalamotomy or Vim DBS improves contralateral tremor.

2. Fragile X tremor-ataxia syndrome (FXTAS) is an ET-like X-linked disorder due to premutation expansions in the FMR1 gene (CGG repeats, 55–200), typically among grandfathers of children with fragile X syndrome. The tremor has a cerebellar component (worsening with action) and patients also exhibit progressive truncal ataxia and cognitive impairment. Family history of mental retardation in children and early menopause or infertility in women are important historical clues. While treatments for ET may work, ataxia and dementia become intractable sources of disability with disease progression. Response to Vim DBS may be short lived.

G. Wilson’s disease is a rare but treatable autosomal recessive disorder of copper accumulation caused by a defect in copper excretion into the bile. Low-plasma levels of ceruloplasmin characterize WD. Copper deposits typically occur in the liver, iris, and basal ganglia. Other organs may be affected as well. A variety of movement disorders can accompany WD, including tremor, dystonia, chorea, dysphagia, dysarthria, and parkinsonism. Symptomatic management of the movement disorder is as discussed in other sections of this chapter.

1. Recommended screening methods for patients with neurologic signs and symptoms of WD are as follows:

a. Serum ceruloplasmin and slit-lamp examination for Kayser–Fleischer (KF) rings. Approximately 90% of WD patients who have neurologic symptoms have a low-ceruloplasmin level. KF rings are present in 99.9% of WD patients who have neurologic symptoms.

b. 24-hour urine copper. In patients with neurologic WD, the 24-hour urine copper level is always more than 100 µg before chelation treatment. This value may be falsely elevated in patients with long-standing liver disease.

2. Copper-rich foods such as shellfish, chocolate, liver, nuts, and soy products should be avoided. However, this is not sufficient to avoid further accumulation, and zinc acetate is used to block mucosal absorption of copper. Zinc acetate is taken at a dose of 50 mg three times a day between meals. The toxicity of zinc is negligible, although it can cause abdominal discomfort. Zinc is the drug of choice for maintenance therapy after chelation and in presymptomatic or pregnant patients.

3. Penicillamine (Cuprimine) acts by means of reductive chelation of copper. It mobilizes large amounts of copper, mainly from the liver. The standard dose after a titration phase is 250 mg four times a day, each dose separated from food. Doses up to 1,500 mg/day can be used. Several potentially serious adverse effects are associated with penicillamine. Approximately 50% of patients treated with penicillamine have marked neurologic deterioration, and half of these patients do not recover to the pre-penicillamine level of function. Approximately one-third of patients who start taking penicillamine have an acute hypersensitivity reaction. Other subacute potential toxicities include bone marrow suppression, membranous glomerulopathy, myasthenia gravis, reduced immune response, hepatitis, pemphigus, and a lupus erythematosus-like syndrome with a positive antinuclear antibody. A CBC with platelets and urinalysis are recommended every 2 weeks for the first 6 months of therapy and monthly thereafter.

4. Trientine (Syprine) is a chelating agent that induces urinary excretion of copper and has a more favorable side-effect profile than penicillamine, with a lower risk of neurologic deterioration (25%), which makes it more favorable for consideration as initial WD treatment. Dosage and administration are identical to those of penicillamine. Although trientine promotes less copper excretion than does penicillamine, it does not cause a hypersensitivity reaction. The other toxicities are somewhat similar to those of penicillamine but less frequent.

5. Tetrathiomolybdate is an experimental drug that prevents absorption of copper from the intestine and is absorbed into the blood, where it binds to copper to form nontoxic complexes. It has been used successfully at a dose of 120 mg/day to manage acute WD with neurologic manifestations.

6. Liver transplantation is curative of WD.

• Exercise should be considered an essential initial and adjunctive treatment for Parkinson’s disease (PD).

• Levodopa is the most effective medical therapy for PD, and therapeutic doses of this medication will bring the most improvement in a patient’s function.

• Treatment of the nonmotor symptoms in PD can improve quality of life as they become a disproportionately greater source of disability with disease progression.

• Treatment of the motor and psychiatric symptoms of Huntington’s disease can benefit from a multidisciplinary approach.

• Tics do not require treatment unless they are troublesome to the patient; cognitive behavioral therapy may be an effective nonpharmacologic intervention.

• Common causes of myoclonus are metabolic, epileptic, and neurodegenerative; treatment should be targeted to the underlying etiology if possible.

• A trial of levodopa is indicated in childhood-onset (predominantly leg) dystonia, in order to assess for the possibility of dopa-responsive dystonia.

• It is generally difficult to completely abate essential tremor, but medical and surgical therapies can diminish its disability.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree