CHAPTER 142 Neoplasms of the Paranasal Sinuses

Sinonasal neoplasms constitute a rare group of tumors in Western society. They account for only 0.2% to 0.8% of all malignancies and 2% to 3% of all head and neck cancers.1,2 The incidence rate, adjusted for age and sex, is 0.3 to 1 case per 100,000 people. These tumors are extremely rare in childhood; the incidence increases with age beginning around the fourth decade. The median age at diagnosis is 62 years in men and 72 years in women, and the male-to-female ratio is 3 : 2.3 The intimate relationships between the nasal passages and sinuses allow easy extension of tumor from one cavity to another. When initially seen, most patients have advanced disease, which is correlated with a less favorable outcome.4,5 This problem is compounded by the proximity of the orbit, brain, and cranial nerves. The techniques of cranial base surgery can extend the anatomic margins of resection and, as part of an aggressive multimodal therapeutic approach, can result in improved oncologic control of these tumors.

Pathogenesis

Epidemiologic studies have shown associations between a variety of environmental hazards and the development of paranasal sinus tumors. Although previously debated,6 a significant association between paranasal sinus tumors and cigarette smoking was demonstrated in a large case-control analysis of white American males.7 The risk doubles in heavy or long-term smokers, and there is a reduction in risk in long-term quitters. A significantly elevated risk for paranasal sinus carcinoma was also found in nonsmokers whose spouses smoked. Other less pronounced associations include increased alcohol intake, high consumption of salted or smoked foods, and decreased intake of vegetables.

The association between exposure to various occupational hazards and the development of paranasal sinus tumors has been the subject of many careful epidemiologic studies (Table 142-1). In an analysis of European case-control studies, occupation was associated with 39% of all sinonasal cancers in men and 11% in women.8 One of the earliest associations was made with nickel refining, where workers’ relative risk for the development of paranasal sinus malignancy was more than 100 times that of the general population.9 With proper management of the workplace environment, one Canadian plant achieved a zero incidence of paranasal sinus carcinoma over a 40-year period.10,11 Adenocarcinoma of the ethmoidal sinus is highly associated with exposure to hardwood dust.12,13 Co-exposure to pigment stains can exert additional risk for adenocarcinoma.12 Furniture makers and wood machinists in England were shown to have a 1000-fold increased incidence of adenocarcinoma of the ethmoid.14–16 In a recent study by Holmila and coworkers, increased expression of cyclooxygenase-2 in sinonasal adenocarcinoma was found in people exposed to wood dust, thus suggesting a role for inflammatory components in the carcinogenesis process.17 The development of paranasal sinus tumors has been linked with exposure to various other agents, including chromium compounds, radium used in watch dial painting, dichlorodiethyl sulfide, isopropyl oil, dust arising during the machining of shoes, textile dust, polyaromatic hydrocarbons in gasoline manufacturing, flour dust, and asbestos.18–21

TABLE 142-1 Occupational Hazards Associated with Paranasal Sinus Tumors

| TUMOR TYPE | OCCUPATIONAL SETTING | SUSPECTED CARCINOGEN |

|---|---|---|

| Squamous cell carcinoma | Nickel refining | Nickel compounds |

| Mustard gas manufacturing | Dichlorodiethyl sulfide | |

| Isopropyl alcohol manufacturing | Isopropyl alcohol | |

| Watch painting | Radium | |

| Adenocarcinoma | Woodworking | Hardwood dust |

| Chrome pigment manufacturing | Chromium compounds | |

| Isopropyl alcohol manufacturing | Isopropyl oil |

Asia and Africa have a relatively high incidence of paranasal sinus tumors. The Bantu of South Africa have the highest incidence worldwide of carcinoma of the upper jaw, which is probably related to the carcinogenic effects of their homemade snuff.22 In Japan, rates are between 2 and 3.6 cases per 100,000 annually, approximately four times that in the American population.18 This higher incidence is mostly due to an increased rate of squamous cell carcinoma of the maxillary sinus, which is thought to be caused by the high prevalence of chronic sinusitis and cigarette smoking in the Japanese.1,23 Fortunately, the incidence of paranasal sinus tumors in Japan seems to be decreasing.24 Adenocarcinoma of the paranasal sinuses is quite rare in Japan, possibly because of the extensive use of softwood rather than hardwood in the Japanese furniture industry.23

There is a well-known association between paranasal sinus tumors and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), especially with T-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.25 The high incidence of sinonasal lymphoma in Uganda is largely due to cases of Burkitt’s lymphoma occurring in that region.18 With the use of in situ hybridization techniques, EBV RNA was found in 7 of 11 cases of sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma (SNUC) in Asian patients, with no EBV RNA found in tumors of the 11 Western patients evaluated.26 However, the Asian patients with EBV-positive SNUC had tumor features designated “lymphoepithelioma-like.” SNUCs of the “Western” type showed morphology typical for this tumor and were negative for EBV. This suggests the presence of separate pathologic entities and a negative association between EBV and SNUC.27

Pathologic Features

Epithelial tumors include squamous cell carcinoma, transitional (schneiderian) carcinoma, and schneiderian papilloma.28 Squamous cell carcinoma accounts for more than half of all paranasal sinus tumors in most series.1,3,29 It most commonly arises from the maxillary antrum, with the ethmoidal sinuses being the second most common site. Most paranasal sinus tumors (80%29) include areas of keratin formation, either as sheets or as epithelial pearls. Less well differentiated nonkeratinizing and anaplastic carcinomas make up the remainder of the lesions. A well-differentiated squamous cell lesion with exophytic growth and little stromal invasion located in the nasal cavity may mimic a papilloma.

Transitional (schneiderian) carcinoma is a special type of nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma that has no particular site of predilection. It is transitional only in that it tends toward squamous cell differentiation.28 Microscopically, it has the appearance of irregular and thickened columnar metaplastic epithelium with closely packed nuclei and multiple mitotic figures. The tumor invades the surrounding stroma at the base. A benign form, transitional cell (schneiderian) papilloma, may be locally recurrent and progresses to carcinoma in approximately 10% of cases.30 Schneiderian papillomas may be exophytic or inverted. The exophytic forms favor a septal location, whereas the inverted types are most often found on the lateral wall of the nasal cavity or in the sinuses.31 An association with carcinoma is strongest for inverted papillomas.28 Human papillomavirus has been associated with the development of schneiderian papillomas.32,33

Glandular tumors include adenocarcinoma and adenoid cystic carcinoma. Adenocarcinoma occurs most frequently in the upper nasal cavity or in the ethmoidal sinuses. It arises directly from surface respiratory epithelium or from the submucosal glands, which are direct epithelial invaginations and thus not true minor salivary glands.34 There are three basic growth forms: papillary, sessile, and alveolar-mucinous.28 Mucin production is variable in the first two forms and abundant in the third. Enteric and nonenteric phenotypes are recognized, both histopathologically and immunocytochemically. Of the two types, the enteric forms are associated with increased recurrence rates independent of margin status or delivery of adjuvant radiotherapy.34 Adenocarcinomas may be well or poorly differentiated, and this high or low grade is related to prognosis.35 The papillary form is the type most often seen in woodworkers and tends to have a relatively better prognosis than the other two.

Another glandular tumor is adenoid cystic carcinoma, which is an uncommon tumor that arises from the minor salivary glands of the mucosa. This tumor occurs mainly in the lower aspect of the nasal cavity. Adenoid cystic carcinoma characteristically infiltrates diffusely, especially along perineural pathways, which contributes to its high rate of recurrence and late metastasis.36 Perineural propagation is usually evident along the maxillary and mandibular divisions of the trigeminal nerve. At times, the site of secondary perineural extension may become apparent before diagnosis of the primary tumor. Careful evaluation usually identifies the primary tumor.37,38 Adenoid cystic carcinoma also has a propensity for bony invasion, which can lead to significant skull base involvement and intracranial extension, thereby making this tumor difficult to treat.39 Microscopically, these tumors have a characteristic appearance consisting of a mixture of microcystic pseudoluminal spaces and tubular epithelium-lined structures, with many lesions also including solid areas. They are typically divided into tubular, cribriform, and solid subtypes. Survival has been found to be best for patients with the cribriform subtype and worst for those with the solid form. Other factors associated with decreased survival time are tumor site, skull base invasion, and tumor stage.38 Tumors arising from the olfactory epithelium are rare neoplasms found in the upper nasal cavity and have been described with many confusing terms, including olfactory neurocytoma, olfactory neuroepithelioma, neuroendocrine carcinoma, esthesioneuroepithelioma, esthesioneurocytoma, neuroblastoma, and esthesioneuroblastoma.40

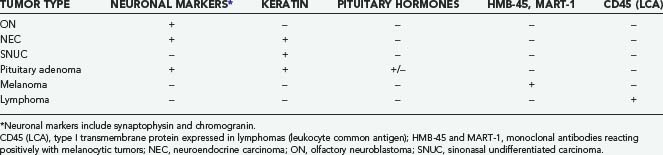

In 1982, Silva and coworkers divided these tumors into two types: ON and NEC.40 Subsequent investigations have identified a number of tumor types that have been grouped under the term sinonasal neuroendocrine tumors, including ON, NEC, small cell carcinoma, and SNUC. ON is typically composed of sheets of uniform small cells with round nuclei, scanty cytoplasm, and prominent fibrillary material between the cells. Homer Wright rosettes (a ring of neuroblastoma cells encircling a small space filled with neurofibrillary material) may be seen. Electron microscopic findings include characteristic neurosecretory (dense-core) granules. NEC is thought to arise from glandular epithelium of the exocrine glands found in the normal olfactory mucosa.40 It thus has a unique admixture with the glandular architecture. There is no neurofibrillary component, and the tumor is composed of solid nests of cells without rosette formation. ON is frequently misdiagnosed41 because tumors such as NEC, pituitary adenoma, melanoma, and SNUC may have a similar histopathologic appearance. Careful analysis of the histopathologic and electron microscopic findings and appropriate use of immunohistochemical analysis should point to the correct diagnosis (Table 142-2).

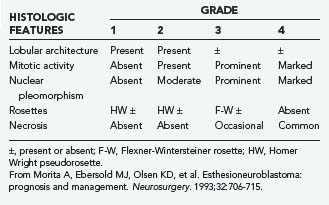

ON and NEC should be considered separate diseases.40,42 NEC arises from a different cell type than ON does, is found more inferiorly in the nasal cavity, and seldom involves the cribriform plate. Furthermore, NEC is predominantly a disease of older patients (mean age, 50 years), is rarely manifested as regional disease, is more prone to distant metastases, and causes death earlier than ON does. Conversely, ON develops more superiorly in the nasal cavity and is more common in younger patients (mean age, 20 years). Finally, NEC has responded well to chemotherapy combined with radiotherapy, whereas the best results with ON have been obtained with surgery and radiotherapy.42 Grading35 and staging43,44 systems for ON have been proposed, with some reports suggesting that pathologic grade is the more reliable predictor of recurrence and survival (Tables 142-3 and 142-4).45,46

TABLE 142-4 Kadish and UCLA Staging Systems for Esthesioneuroblastoma

| Kadish Staging | |

| Group A | Tumor confined to the nasal cavity |

| Group B | Tumor extending into the paranasal sinuses |

| Group C | Tumor spreading beyond the nasal and paranasal cavities |

| UCLA Staging | |

| T1 | Tumor involving the nasal cavity and/or paranasal sinuses (excluding the sphenoidal sinus), with sparing of the most superior ethmoidal cells |

| T2 | Tumor involving the nasal cavity and/or paranasal sinuses (including the sphenoidal sinus), with extension to or erosion of the cribriform plate |

| T3 | Tumor extending into the orbit or protruding into the anterior cranial fossa |

| T4 | Tumor involving the brain |

UCLA, University of California at Los Angeles.

From Dulguerov P, Calcaterra T. Esthesioneuroblastoma: the UCLA experience 1970-1990. Laryngoscope. 1992;102:843-849.

SNUC and small cell carcinoma are rare aggressive tumors that histologically may be confused with ON, NEC, lymphoma, or melanoma. Features of these tumors include a brisk mitotic rate, prominent cellular pleomorphism and hyperchromatic nuclei, and regions of tumor necrosis and vascular invasion.47 There is a high rate of early metastatic dissemination, especially in the small cell variety, and patients rarely live beyond 2 years.48–50 Rosenthal and colleagues found 5-year overall survival rates of 93.1%, 64.2%, 62.5%, and 28.6% for ON, NEC, SNUC, and small cell carcinoma, respectively.51

Other less common malignant tumors of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses include mucoepidermoid carcinoma, melanoma, plasmacytoma, lymphoma, germ cell tumors, and various sarcomas.52 Although malignant tumors are more common overall, benign lesions such as schneiderian papillomas (discussed earlier), osteomas, and chondromas may occur. Other tumors involve the region by direct extension from adjacent sites, such as juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma, chordoma, meningioma, nerve sheath tumors, and pituitary tumors.53,54 Metastases to the sinonasal region are rare. Renal cell carcinoma is by far the most common infraclavicular source of metastases to this area, followed by lung and breast cancer.55 Table 142-5 demonstrates the histologic distribution of paranasal sinus tumors treated by the senior author in the Department of Neurosurgery at The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center (M. D. Anderson) between 1992 and 2008. Because this is a neurosurgical series, there is a referral bias for advanced disease with intracranial or orbital extension, which has resulted in a somewhat different distribution of histologic types than noted in other reports.

TABLE 142-5 Histologic Distribution of Paranasal Sinus Tumors in 209 Patients Treated by Craniofacial Resection at The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, 1992 to 2008

| TUMOR TYPE | NO. OF PATIENTS |

|---|---|

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 35 |

| Olfactory neuroblastoma | 28 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 23 |

| Adenoid cystic carcinoma | 21 |

| Sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma | 13 |

| Osteosarcoma | 11 |

| Neuroendocrine carcinoma | 7 |

| Angiofibroma | 7 |

| Melanoma | 6 |

| Chondrosarcoma | 6 |

| Fibrosarcoma | 5 |

| Low-grade unclassified sarcoma | 4 |

| Inverting papilloma | 4 |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | 4 |

| Nerve sheath tumor | 3 |

| Meningioma | 3 |

| Malignant fibrous histiocytoma | 3 |

| Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor | 2 |

| Mucopyocele | 2 |

| Benign fibrous tumor | 2 |

| Metastases | 5 |

| Singular pathologies* | 15 |

* Includes mucoepidermoid carcinoma, mesenchymal chondrosarcoma, teratocarcinosarcoma, angiosarcoma, osteoma, leiomyosarcoma, fibrovascular polyp, ameloblastic carcinoma, primitive neuroectodermal tumor/Ewing’s sarcoma, high-grade unclassified sarcoma, malignant solitary fibrous tumor, germ cell tumor, myoepithelial carcinoma, liposarcoma, and hemangioma.

It is often difficult to determine the site of origin of these paranasal sinus neoplasms because more than 90% have invaded at least one sinus wall55 and disease may extend well beyond the original sinus.56 The most common location is the maxillary sinus, where 55% of tumors originate. The rest of the paranasal sinuses account for about 10% of cases, with 9% arising from the ethmoidal sinus and only 1% from the sphenoidal and frontal sinuses. In 35% of cases, the tumor originates from within the nasal cavity.18

Diagnostic Evaluation

Table 142-6 summarizes the common initial features of paranasal sinus malignancies. Most patients exhibit many of these symptoms and signs.28 The signs and symptoms of maxillary sinus tumors have been grouped by regional anatomy into nasal, oral, ocular, facial, and neurological findings.57 The most common initial symptom is nasal airway obstruction, frequently unilateral, followed by chronic nasal discharge and epistaxis.29,58 Extension of the neoplasm into the nasal cavity may be seen on anterior rhinoscopy (Fig. 142-1). Oral findings include unexplained pain in the maxillary teeth because of involvement of the posterior superior alveolar nerve. Further expansion may cause loosening of teeth, malocclusion, and trismus. Fullness of the palate or alveolar ridge may lead to ill-fitting dentures in an edentulous patient.59 Tumor bulging into the oral cavity from an adjacent sinus may be visible. Ocular symptoms occur with upward extension into the orbit and include unilateral tearing, diplopia, proptosis, epiphora, and fullness of the lids. Facial findings most often result from involvement of the anterior antral wall. There may be facial asymmetry with cheek swelling; in advanced cases, ulceration and fistulas may develop on the face. Numbness, paresthesia, and pain may result from involvement of the infraorbital nerve or, in more advanced disease, from posterior extension of the tumor into the pterygopalatine fossa with involvement of the entire maxillary division of the trigeminal nerve.59

TABLE 142-6 Common Symptoms in 200 Patients with Malignant Tumors

| SYMPTOM | NO. OF PATIENTS (%) |

|---|---|

| Nasal airway obstruction | 89 (44.5) |

| Nasal discharge | 78 (39) |

| Bloody or blood-tinged discharge | 51 (25.5) |

| Mucus | 27 (13.5) |

| Facial pain | 77 (38.5) |

| Mass in the nasal cavity | 72 (36) |

| Exophthalmos | 47 (23.5) |

| Swelling in the cheek | 43 (21.5) |

| Paresthesia | 39 (19.5) |

| Epiphora | 30 (15) |

| Diplopia | 27 (13.5) |

| Decreased vision | 21 (10.5) |

Modified from Weber AL, Stanton AC. Malignant tumors of the paranasal sinuses: radiologic, clinical and histopathologic evaluation of 200 cases. Head Neck Surg. 1984;6:761-776.

FIGURE 142-1 Tumor tissue and old blood are visible at the nasal vestibule in a patient with a massive sinonasal adenocarcinoma.

(Courtesy of The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, Department of Neurosurgery, Houston, TX.)

Tumors of the upper nasal cavity and ethmoid may extend through the cribriform plate into the anterior cranial fossa and are associated with anosmia and headache. Carcinoma of the frontal sinus may be manifested as acute frontal sinusitis with pain, swelling over the sinus, and evidence of early bone erosion.60 Unlike most paranasal sinus tumors, nasal obstruction, epistaxis, and nasal discharge may be absent when the tumor is located in the sphenoidal sinus. Patients with sphenoidal sinus tumors most commonly suffer from headache, diplopia, and cranial neuropathies.61

Lymph node involvement or metastatic disease is present in less than 10% of patients at initial evaluation,58,62 although the incidence increases throughout the course of the disease. Lymphatic metastasis may occur more frequently than recognized because of inaccessibility of the retropharyngeal nodes for examination.60

Advanced disease is the most accurate predictor of poor outcome.4 Unfortunately, the early symptoms of malignant paranasal sinus tumors are identical to those of benign nasal and paranasal sinus disease.5,63 Combined physician and patient delay ranges from 3 to 14 months.64 With heightened physician awareness, the liberal use of imaging studies, and early biopsy, the median patient-physician delay is reduced from 8 to 4 months, with 33% of tumors being diagnosed at an early (T1 or T2) stage.

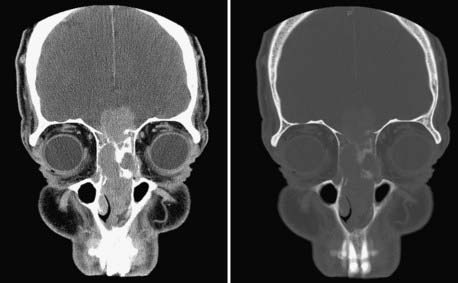

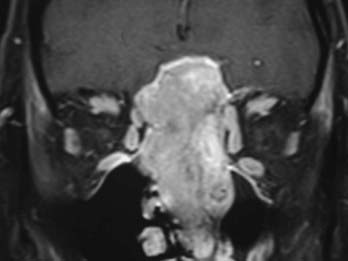

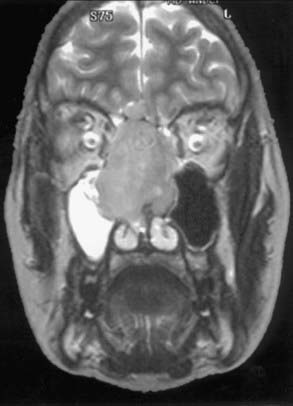

Evaluation of these patients involves a thorough examination of the head and neck, including endoscopic evaluation of the sinonasal and nasopharyngeal regions. The cranial nerves must be evaluated, and all patients should have a baseline neuro-ophthalmologic review. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are complementary studies and the imaging methods of choice for assessing these tumors.65,66 CT is particularly useful for assessing bony changes, especially erosion. Direct coronal CT is best for assessing the integrity of the anterior skull base, including the orbital roof, cribriform plate, and planum sphenoidale (Fig. 142-2). The extent of tumor is best seen with MRI (Fig. 142-3), which can also differentiate tumor from inflamed mucosa, blood, or inspissated mucus in most cases (Fig. 142-4).67 Signal voids within the tumor identified by MRI or proximity of the neoplasm to the internal carotid artery may be an indication for preoperative angiography to assess tumor vascularity and plan surgical treatment. Postoperative use of positron emission tomography/CT can help distinguish between postoperative changes and recurrence or residual tumor.66

The key to diagnosis and management is biopsy. Flexible endoscopes permit access to most tumors of the paranasal sinuses. In the case of deep-seated lesions, CT-guided needle biopsy may be performed. The importance of evaluation of the biopsy specimen by an experienced pathologist cannot be overemphasized.68

Classification

Many classification systems are currently in use to stage maxillary sinus tumors, all based on the TNM (tumor, node, metastasis) system.69 Because nodal and distant propagation is uncommon and occurs very late in the disease, the T stage is of paramount importance. There is no single widely accepted staging system for ethmoid carcinoma.69–72 The 2007 American Joint Committee on Cancer classification of maxillary and ethmoidal sinus tumors is presented in Table 142-7.

TABLE 142-7 American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging of Carcinoma of the Maxillary and Ethmoid Sinuses

From American Joint Committee on Cancer. AJCC Staging Manual, 7th ed. New York: Springer; 2007.

Principles of Treatment

Tumor pathology and extent of disease, the availability and potential success rates of adjuvant therapies, and the potential for functional impairment and aesthetic deformity are all important parameters to consider when planning the best management options for a patient with a paranasal sinus tumor, which also makes it difficult to generalize and study various treatment options. In most cases, surgery and radiation therapy are used as a combined treatment modality, but other adjuvant therapies such as radiosurgery and chemotherapy may be indicated. It is important to note that management of paranasal sinus tumors is a multidisciplinary endeavor. Assistance and consultation from a team of specialists are required (Table 142-8). The prime parameters that drive management decisions are tumor pathology, the ability to achieve gross total resection, and the availability of adjunctive therapies.

TABLE 142-8 Multidisciplinary Team Members Involved in the Management of Paranasal Sinus Tumors

| Neurosurgery |

| Head and neck surgery |

| Plastic surgery |

| Ophthalmology |

| Dental oncology |

| Diagnostic imaging |

| Pathology |

| Medical oncology |

| Radiation oncology |

Initially, consideration is given to whether gross total excision can be accomplished. For adenocarcinoma and adenoid cystic carcinoma, it is our preference to begin with surgical excision, followed by external beam irradiation. If the patient has previously received radiotherapy, induction chemotherapy should precede surgical excision and be continued postoperatively if a response is obtained. Induction chemotherapy is also used for squamous cell carcinoma in the context of an “organ-sparing” (usually orbit-sparing) approach.73

Surgical Management

The goal of surgical management is to achieve complete tumor resection with a margin of normal tissue. Early reports of treatment of paranasal sinus tumors by local resection (e.g., maxillectomy) combined with radiotherapy were disappointing, with an overall 5-year survival rate of less than 30%.64 Lesions were incompletely excised because of technical difficulties in carrying out thorough en bloc resections.

Smith and coauthors reported the first craniofacial resection for malignant disease of the ethmoidal sinus involving the cribriform plate 74 Ketcham and associates first reported combined frontal craniotomy and maxillectomy to treat malignant tumors75 and later updated their experience with much improved survival rates.76 Terz and colleagues further extended the limits of resection to include the middle cranial fossa so that the pterygoid plates and their attachments to the sphenoid bone could be removed.77

Craniofacial Resection

Patients are selected for craniofacial resection because of involvement of the ethmoidal sinus or cribriform plate by tumor or because of suspicion of dural invasion based on preoperative imaging studies. Most purely ethmoidal tumors can be excised transcranially without the need for facial incisions.78,79 An open transfacial or endoscopic approach is needed if the tumor extends to the anterior nasal cavity or laterally beyond the medial third of the maxillary sinus. In most patients the transcranial approach is performed first, followed, if necessary, by transfacial entry into the paranasal sinuses. This sequence minimizes contact between the sinuses and epidural space until after repair of the frontobasal dura. Broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics (vancomycin, ceftazidime, and metronidazole) are administered in the perioperative period.68

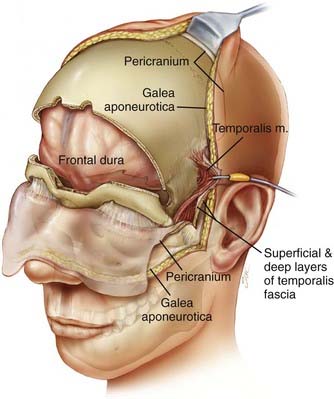

The patient is placed in the supine position with the head supported by a horseshoe headrest or affixed in a rigid cranial clamp. A bicoronal incision is carefully opened to expose the galea. The galea is opened sharply and dissected from the underlying loose connective tissue. Care is taken to preserve the anterior branches of the superficial temporal arteries. The scalp flap is reflected anteriorly by dissecting immediately below the galea, thus maximizing the thickness of the loose connective tissue layer overlying the periosteum. The posterior aspect of the scalp flap is undermined to maximize the length of the pericranial flap. Incisions are made bilaterally through both the superficial and deep layers of the temporalis fascia approximately 1.5 cm above the zygomatic process of the frontal bone and carried posteriorly for approximately 2 to 3 cm. Incisions in the periosteum are made at the level of the superior temporal line bilaterally and extended posteriorly from the previously described fascial incisions. These incisions are carried under the posterior scalp flap and then joined across the top of the head to circumscribe the pericranial flap. The pericranial flap is then elevated and reflected anteriorly. With a sharp periosteal elevator, the pericranial tissue is dissected from the orbital rims and from the zygomatic process of the frontal bone. The anterior portion of the temporalis muscle is dissected from the temporal fossa and reflected posteriorly. This gives access to the “keyhole” regions bilaterally. Entry holes are placed in both keyhole regions and at the superior sagittal sinus. A free bifrontal craniotomy is elevated. Because most of the work will be in the midline, the bone flap is extended inferiorly to just above the frontonasal suture (Fig. 142-5).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

,

,