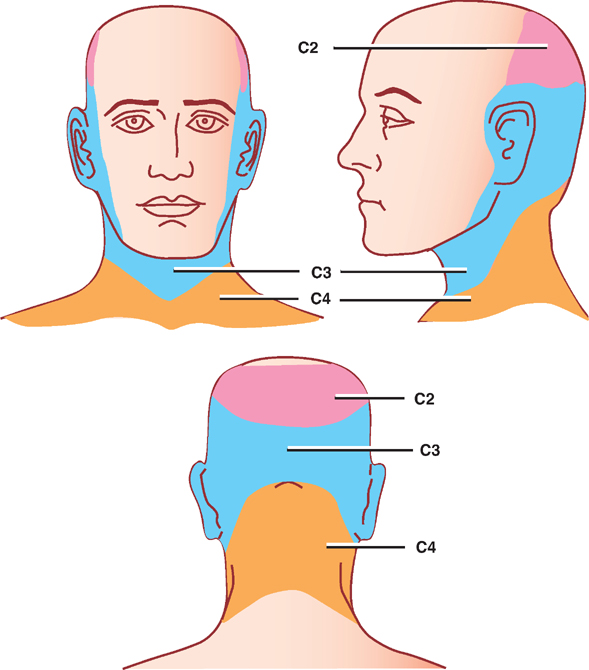

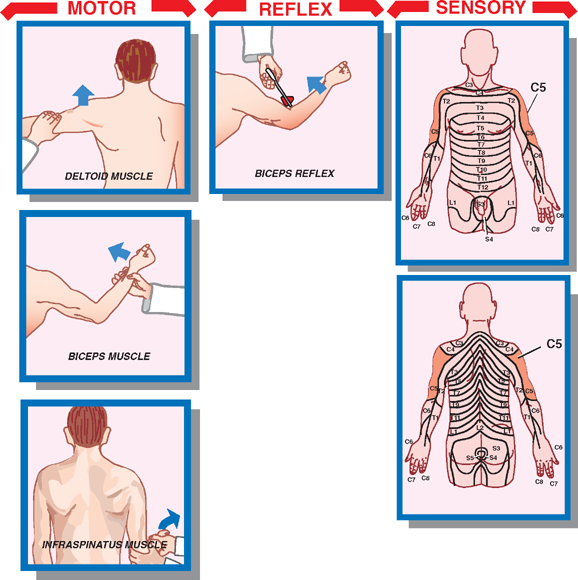

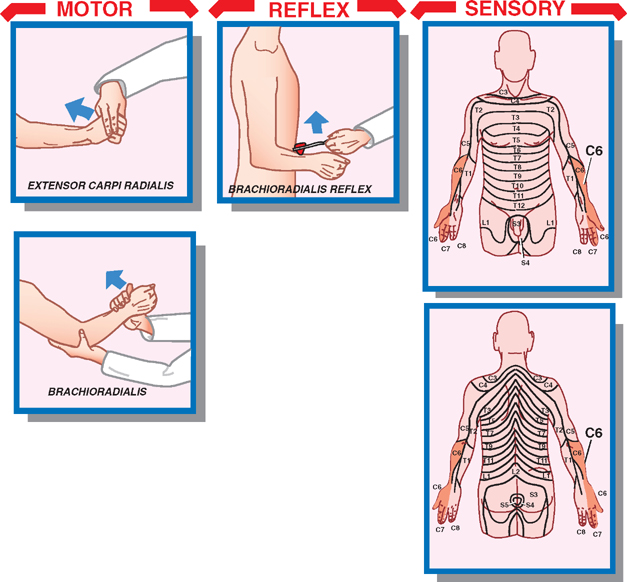

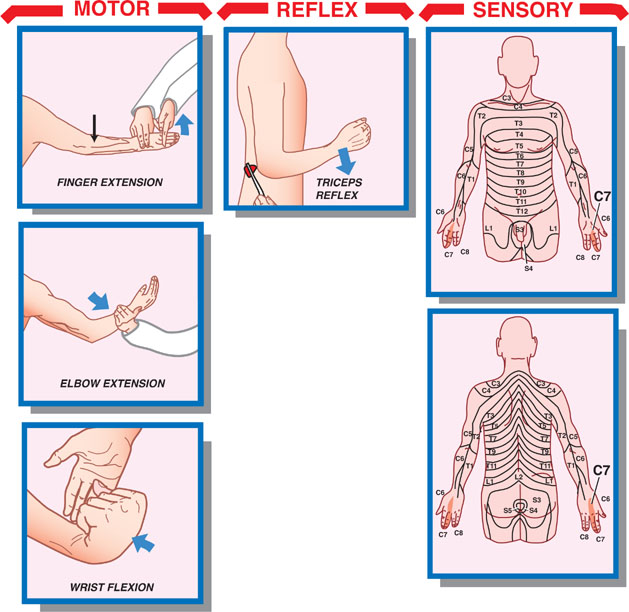

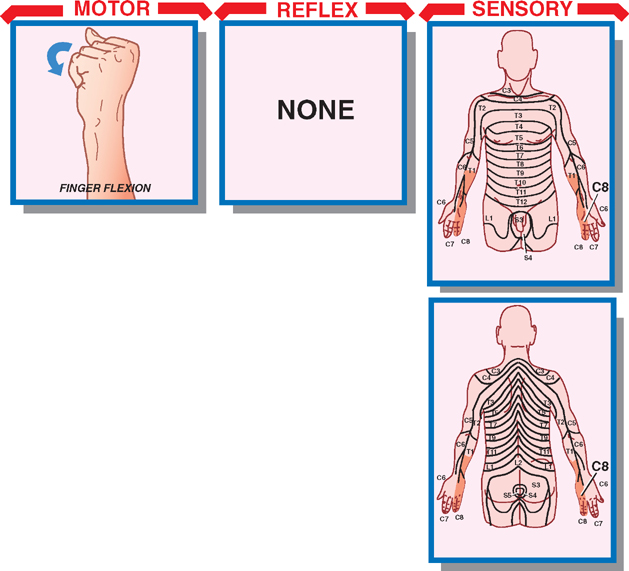

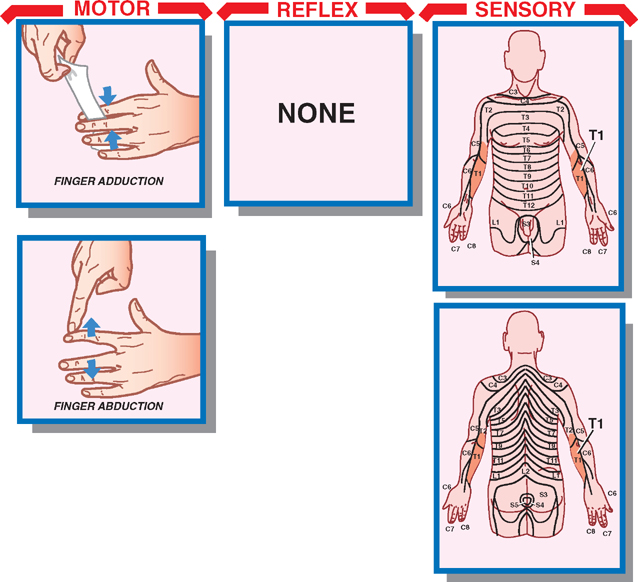

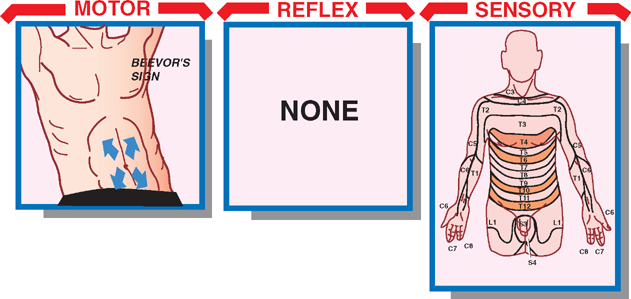

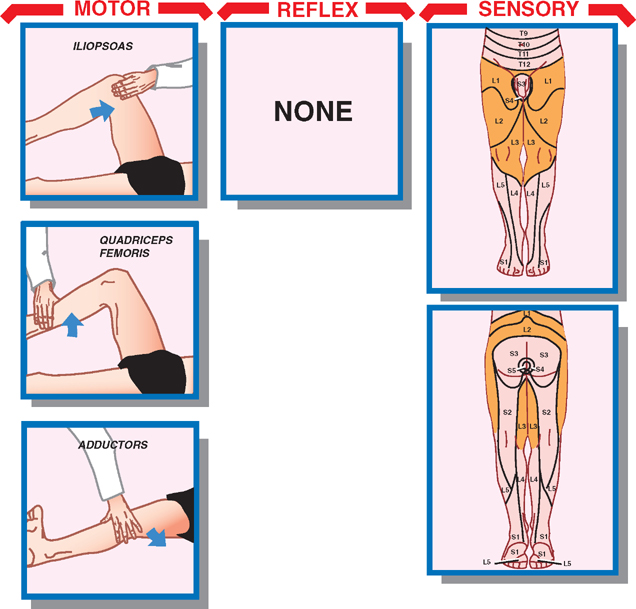

4 Nerve Roots and Spinal Nerves A ventral and dorsal nerve root exits the spinal cord at each segmental level, carrying motor and sensory fibers, respectively. The nerve roots in each pair unite and combine with autonomic fibers to form a spinal nerve, which exits the vertebral column through the intervertebral foramen to give rise to nerve plexuses and peripheral nerves. There are 8 cervical nerves, 12 thoracic nerves, 5 lumbar nerves, 5 sacral nerves, and 1 coccygeal nerve. The most clinically significant spinal nerves are the C5–T1 segments, which together form the brachial plexus, providing innervation to the upper extremities, and the T12–S4 segments, which together form the lumbosacral plexus, providing innervation to the lower extremities. A group of muscles that is innervated by a single spinal nerve is termed a myotome, and the area of skin that receives sensory innervation from a single spinal nerve is termed a dermatome. This strict organization of clinically relevant motor and sensory innervation patterns provides an excellent opportunity for neurologic diagnosis. After a brief discussion of the anatomy of the nerve root and spinal nerve, this chapter presents the motor, sensory, and reflex examination of lesions affecting the nerve roots and spinal nerves. At each segmental level, a dorsal nerve root is formed that contains afferent sensory fibers. The cell bodies of these fibers, which enter the spinal cord through the dorsolateral sulcus, are located in an adjacent dorsal root ganglion. Likewise, ventral efferent fibers, which originate in the cell bodies of the ventral gray horn, exit the spinal cord in a ventral nerve root. The dorsal and ventral nerve roots unite to form a spinal nerve, which exits the vertebral column through its corresponding intervertebral foramen. After emerging from the foramen, the spinal nerve divides into dorsal and ventral rami. The small dorsal ra-mus turns back to supply the skin of the dorsal aspect of the trunk and the longitudinal muscles of the axial skeleton. The larger ventral ramus supplies sensory and motor innervation to the limbs, the nonaxial skeleton, and the skin of the lateral and ventral aspects of the neck and trunk. The ventral ramus also communicates with the sympathetic chain via the white and gray rami communicantes. The unique character of the nerve roots and spinal nerves lies in their segmental pattern of organization. This distinguishes lesions involving these structures from lesions involving the peripheral nerves and nerve plexuses. The diagnosis of lesions of the nerve roots and spinal nerves thus rests on an orderly evaluation of pertinent myo-tomes and dermatomes (i.e., a directed motor, sensory, and reflex examination). Every muscle that is innervated by a single spinal nerve or group of spinal nerves need not be examined, or even learned. Rather, it is important to develop a directed examination that identifies a lesion as segmental in character and that correctly localizes the segmental level. The balance of this chapter provides the anatomic basis and the examination methods needed to accomplish this. See Fig. 4.1. Lesions involving the C1 to C4 nerve roots are especially difficult to evaluate. These nerve roots supply innervation to the muscles and skin of the neck and the head. Significantly, they also contribute to the diaphragm (C3–C5). Because of the difficulty in examining the head and neck muscles, the best method of evaluating this group of nerve roots is to examine their sensory distribution. Fig. 4.1 C2–C4 dermatomes. See Fig. 4.2. The most readily tested muscles that derive from the C5 nerve root are the deltoid and biceps muscles. The deltoid muscle receives pure C5 supply and is innervated by the axillary nerve. The biceps muscle is supplied by both C5 and C6 and is innervated by the musculocutaneous nerve. The most important action of the deltoid muscle is shoulder abduction, which it shares with the supra-spinatus muscle (C5, C6; suprascapular nerve). The most important action of the biceps muscle is elbow flexion, which it shares with the brachialis muscle (C5; muscu-locutaneous nerve). Therefore, to test the motor integrity of the C5 nerve root, examine shoulder abduction and elbow flexion. The C5 nerve root supplies the lateral aspect of the arm (axillary nerve). The purest portion of its sensory innervation is a patch of skin on the lateral aspect of the deltoid muscle. The biceps reflex is primarily dependent on the integrity of C5, although it is also partly supplied by C6. Because it receives supply from two segmental levels, compare the biceps reflex on each side; an asymmetry may be indicative of a C5 root lesion. Fig. 4.2 Neurologic tests for C5 lesion. See Fig. 4.3. The wrist extensor group and the biceps muscle both receive their major supply from the C6 nerve root, via the radial nerve and musculocutaneous nerve, respectively. However, the wrist extensor group is also partly innervated by the C7 root (ulnar nerve), and the biceps muscle is also partly innervated by the C5 root (musculocutane-ous nerve). Weakness in wrist extension due to isolated C6 compromise results in ulnar deviation during wrist extension. As mentioned, the biceps muscle receives motor innervation from both the C5 and C6 nerve roots. The recommended test of biceps muscle function is elbow flexion. Unilateral weakness of elbow flexion may be indicative of injury to the C6 nerve root. The C6 dermatome comprises the lateral forearm, the thumb, the index finger, and one half of the middle finger. The deep tendon reflexes of the upper extremity that receive supply from C6 include the biceps reflex (C5–C6) and the brachioradialis reflex (C6). Because the brachio-radialis reflex receives pure C6 innervation, it is the best reflex to use to test the C6 nerve root. Fig. 4.3 Neurologic tests for C6 lesion. See Fig. 4.4. The triceps muscle (radial nerve), wrist flexors (median and ulnar nerves), and finger extensors (radial nerve) are all predominantly innervated by C7. To examine the integrity of the C7 nerve root, test each of these three groups of muscles. Elbow extension is the best test of the triceps muscle. A C7 lesion results, then, in weakness of elbow extensions. Wrist flexion is primarily due to the flexor carpi radialis (C7; median nerve) and, to a lesser degree, the flexor carpi ulnaris (C8; ulnar nerve). With C7 lesions, wrist flexion results in an ulnarward deviation. C7 supplies sensory innervation to the middle finger. However, because the middle finger may also receive supply from C6 or C8, sensory evaluation of the C7 nerve root is not reliable. The triceps reflex receives innervation from the C7 component of the radial nerve and is a reliable test of C7 function. Fig. 4.4 Neurologic tests for C7 lesion. See Fig. 4.5. The muscles of finger flexion (median and ulnar nerves) are supplied by C8. To evaluate the motor innervation of C8, test finger flexion. The sensory innervation supplied by C8 includes the ring and little fingers of the hand and the distal half of the medial aspect of the forearm. Fig. 4.5 Neurologic tests for C8 lesion. See Fig. 4.6. Finger abduction (T1; ulnar nerve) and finger adduction (C8, T1; ulnar nerve) both receive supply from the C8 nerve root. To test finger adduction, place a piece of paper between two of the patient’s extended fingers and attempt to pull the paper away. Compare the strength of finger adduction on both sides. The sensory innervation of T1 includes the upper half of the medial forearm and the medial portion of the arm. Fig. 4.6 Neurologic tests for T1 lesion. See Fig. 4.7. Lesions of T2 to T12 are discussed together in this section because they are primarily evaluated by sensory testing (i.e., dermatomal identification). Muscles that are innervated by the T2 to T12 nerve roots comprise the intercostals and the rectus abdominal muscles. The intercostal muscles, although they are innervated segmentally, are difficult to examine individually. Asymmetric weakness of the rectus abdominal muscles may be identified by the presence of Beevor’s sign. Beevor’s sign is present when the umbilicus of the patient is drawn up or down, or to one side or the other, when the patient is a quarter way through a sit-up. Sensory examination is performed in the usual manner, with particular attention directed to the identification of dermatomal involvement. Useful reference points include the nipples (T4), the xyphoid process (T6), the umbilicus (T10), and the inguinal ligament (T12). Note the oblique angles assumed by the dermatomes of the trunk. Fig. 4.7 Neurologic tests for T2–12 lesion. See Fig. 4.8. No specific muscles receive supply from the individual segmental nerve roots between the L1 and L3 levels, but important muscles are innervated by a combination of nerve roots at these levels. These include the iliopsoas (L1–L3), the quadriceps (L2–L4; femoral nerve), and the adductor muscles (L2–L4; obturator nerve). Sensory testing is especially important in this region because of the lack of specificity in muscle testing. The L1 dermatome comprises an oblique band just below the inguinal ligament; the L3 dermatome comprises an oblique band just above the knee; and the L2 dermatome comprises an oblique band located between L1 and L3. Fig. 4.8 Neurologic tests for L1–L3 lesion. See Fig. 4.9. The tibialis anterior muscle receives its predominant supply from the L4 nerve root (deep peroneal nerve). This muscle is responsible for dorsiflexion and inversion of the foot, and may be tested by asking patients to walk on their heels, or by manually resisting dorsiflexion and inversion of the foot. The latter L4 function may be helpful in distinguishing an L4 radiculopathy from a peroneal nerve palsy because the peroneal nerve does not innervate the foot invertor (tibialis posterior muscle; tibial nerve). The L4 dermatome covers the medial side of the leg below the knee. Its anterior boundary with the L5 dermatome is marked by the sharp crest of the tibia. The patellar reflex receives its predominant supply from the L4 nerve root. An L4 injury, however, may not completely eradicate the reflex because it receives a smaller supply from L2 and L3.

Anatomy of the Nerve Roots and Spinal Nerves

Principles of Nerve Root and Spinal Nerve Localization

Anatomy and Examination of Spinal Nerve and Nerve Root Lesions

C1 to C4 Lesions

C5 Lesions

Motor

Sensory

Reflexes

C6 Lesions

Motor

Sensory

Reflexes

C7 Lesions

Motor

Sensory

Reflex

C8 Lesions

Motor

Sensory

T1 Lesions

Motor

Sensory

T2–T12 lesions

Motor

Sensory

L1–L3 Lesions

Motor

Sensory

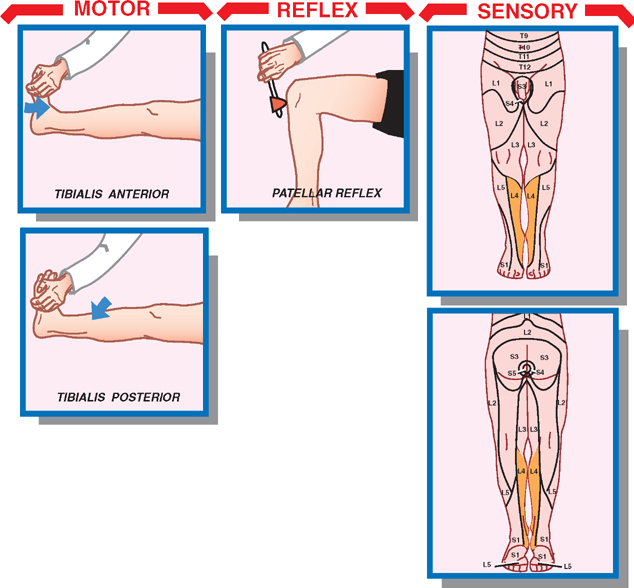

L4 Lesions

Motor

Sensory

Reflex

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree