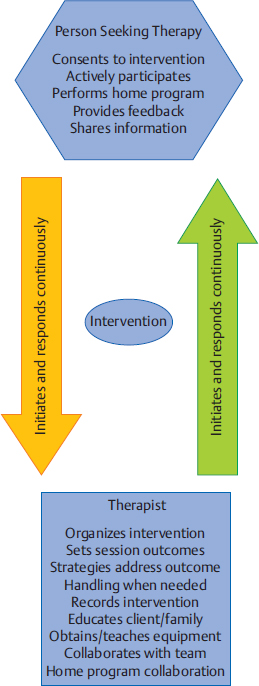

9 Neuro-Developmental Treatment Intervention—A Session View This chapter describes the process of designing and implementing a single intervention session from the perspective of the client, family, and therapist within the context of the Neuro-Developmental Treatment (NDT) Practice Model. The rationale for setting a session outcome, performing a pre- and posttest, and implementing intervention that includes preparation, simulation, progression, and practice of meaningful tasks is described in a way that the reader can identify a problem-solving process that is continuous and interweaving in design. In addition to engagement of the client with the therapist, client and family education, assistive technology, therapy equipment, and home programming are also described as they are integrated within and between sessions. Clinical examples are given throughout the chapter to illustrate the concepts. The chapter concludes with planning for the following intervention session. Throughout the chapter, examples of real-life intervention sessions illustrate the topic descriptions. Learning Objectives Upon completing this chapter the reader will be able to do the following: • Delineate among the roles of the client, therapist, family members, and other team members in the NDT intervention process. • Recognize the continuous decision-making process of setting the session outcome among client, family, and therapist, and the integration of relevant and meaningful functional activities throughout the session. • Describe the integration of contextual factors, including environmental and personal factors throughout the intervention process, both in the planning and in the session itself. • Discuss the process and purposes of the pretest, preparation, simulation, practice, home programs, education, and posttest within the intervention session. • Analyze the role, gradation, timing, and weaning of therapeutic handling, including key points of control (KPCs), facilitation, and inhibition within the context of a single intervention session. • Define the role of assistive technology and therapeutic equipment within a session and in the home, school, or community environments. Intervention is the action piece of the integrative process of decision making within the Neuro-Developmental Treatment (NDT) Practice Model that brings the client and clinician together to make logical choices toward successful outcomes (Fig. 9.1). In previous chapters, information gathering, examination, evaluation, and the plan of care were described in detail. These components continue to be important parts of intervention because the clinician must continually be gathering information, examining, evaluating, and altering the plan of care in the moment throughout the intervention session as needed. This constant listening, observing, examining, and responding to changing information is critical to the NDT Practice Model and can be observed and heard in each intervention session. Intervention is the part of the plan of care that the clinician puts into action as strategies to address the restrictions in participation, limitations in activity, and impairments in body systems. During the intervention session, the clinician applies procedural knowledge to achieve functional outcomes that have been written in the plan of care, with problem solving in the moment to address the therapeutic needs of the client in all International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) domains: participation, activity, and body systems, in functional contexts. All domains are addressed within each intervention session. This chapter describes the development of a session plan, the individualized therapeutic process for the session, options for modulating or progressing within a session, as well as specific intervention strategies that represent the NDT Practice Model. In addition, a collection of potential frameworks or principles for developing intervention strategies is presented toward the end of the chapter. Each intervention session is an expression of all of the core philosophical tenets, assumptions, and key principles of the NDT Practice Model presented in Unit I. As such, it should be clear that the individual seeking therapy is the focus and heart of each session. The client is viewed as the center or leader of the intervention team who works together with others to reach outlined outcomes. The team can include the individual, his or her family or caregivers, and the extended social, medical, and educational team. The person seeking therapy, however, and his or her family, identify the functional goals that are to be the focus of the intervention. Those identified desired participations and activities become the outcomes around which the long-term intervention process is designed, as well as becoming the focus of each individual session. Each individual has many ways to participate and a variety of activities that she or he wants to regain or improve upon. All of these choices drive intervention decisions. Each session is therefore designed considering this one individual with all her individual integrities and impairments, one specific outcome of an activity or a participation role, and one unique blend of contextual factors, including both environmental and personal facilitators and barriers for that activity. Each session is organized around this specific session outcome. The individual is an active participant in every aspect of each session, and the therapist works to build on the individual’s strengths while addressing the individual’s impairments and activity limitations. Intervention itself includes a hands-on aspect within the examination, evaluation, and intervention process within the session. The intervention session is individualized based on the ongoing synthesis of information gained from the examination and intervention process and therefore includes continual examination and evaluation. The session includes education with the client and family or caregivers and a plan for active practice throughout daily life, a critical component for permanent integration into postural and movement control. Each person who comes to an intervention session is a unique being. This person brings not only specific diagnoses, impairments, and limitations but also unique strengths, hopes, and goals. Each person has a different history or varying life experiences with different family and community influences. In some sessions, the therapist may meet and only know the client as an individual if no family members are present. In other cases, the entire family may be active participants in intervention sessions and may be instrumental throughout the intervention process. For example, if one considers an early intervention session with an infant who was born prematurely, the parent–child team may be viewed jointly as the client. At the beginning of the intervention planning process, the client, the family/caregivers, and the therapist create a therapeutic relationship. This relationship may be new, having been forged a few minutes earlier during the examination and evaluation process, may be ongoing, when the client is continuing within an existing plan of care, or may be decades old, when beginning a new episode of care. The therapeutic relationship will continue to evolve and change during the intervention, and the relationship among them will have an influence on the intervention process. People who seek occupational therapy, physical therapy, and/or speech-language therapy from a therapist who practices within an NDT framework can anticipate that they will have an active presence in the planning of their intervention program and that they will be actively engaged in each step of the process. They expect that their goals, needs, wants, and dreams will drive the development of the plan of care and will frame the focus of each and every intervention session. Their responsibility is to share with the therapist the participation and activities they value. They will need to describe their home life and the key environments in which they currently function or would like to return to and changes in their lives as they occur so that therapeutic intervention can be adapted accordingly. Also, they need to reveal information concerning their body systems, including both integrities and impairments. They anticipate that therapy will be active and that they will work hard during an intervention session. They also know that part of the intervention requires them to provide honest feedback during and between sessions as to the effect of strategies experienced during a session. They understand they are expected to continue the therapeutic process outside of the session through active participation in their home program. As stated previously in this chapter, there is a constant interaction between the therapist and the client (and family/caregiver if involved). The plan evolves based on the needs, desires, and outcomes of the client. When clients and families are unfamiliar with NDT’s philosophy of care, the NDT practitioner assumes the added responsibility of education about the intervention process. Consumers develop an appreciation for their expected active involvement and the different roles and responsibilities they will assume. The therapist understands that for the session to have meaning, the outcomes of the session must be grounded in real-life function, and this function must have meaning to the individual now and in the future. A therapist using an NDT practice framework understands that care will be provided within a discipline-specific scope of practice. A practitioner of NDT understands that current evidence informs practice decisions when developing and implementing a plan of care with the client and also understands that principles of best practice include consideration of client preference, clinician skill, and expertise. This expertise includes previous therapeutic relationship experiences with this client and other clients that will influence the decision-making process during both the planning and the implementation phases of intervention. The therapist gathers information during the examination of the individual from all domains within the ICF model, but during intervention sessions, this information is enhanced and enriched as time allows more detailed information sharing in a less structured and informal format. For example, during information gathering, it may be reported that an adult client is unable to cook her own meals or meals for her husband. The improvement of this participation restriction may be perceived as an appropriate outcome toward which the therapist will work. However, as intervention progresses, this client might reveal that she never has cooked and that role has always been performed by her husband or that she cooked prior to her stroke but never really enjoyed it. What she did enjoy though was gardening. Her personal goal would be to return to her hobby as a gardener and to have the intervention focus on this activity/participation. The specific impairments that are limiting her ability to return to gardening become the focus of the intervention. What is true, however, and critical to note for therapists who feel constrained by the standard list of outcome activities used in many health care facilities, such as bed mobility, bed and wheelchair transfers, toileting, feeding/eating (and which are often dictated by the reimbursement schedule), is that an individual possesses only one set of impairments. This one set of impairments interferes with all the individual’s activities and participations. The influence or weighting of impairments may vary from one activity to another, but there is not a different set of impairments for each activity limitation. In this example, if the intervention focus is on the impairments interfering with the tasks and subtasks of the activity of gardening (and the other activities this individual has identified as meaningful to her), as these impairments are reduced or eliminated, this improvement will also influence her ability to perform many of her other daily activities and participations, such as dressing for work, walking in the community, transfers, and cooking for her family if she is so inclined (Fig. 9.2). Laurence J. Peter and Raymond Hull of the Peter Principle1 wrote, “If you don’t know where you are going, you will probably end up somewhere else.” Lewis Carroll,2 from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, is often paraphrased as writing, “If you don’t know where you are going, any road will get you there.” These are two wise statements to heed in the intervention process with clients. Helping clients achieve sustainable, meaningful, functional outcomes is the end goal of the therapeutic process of the NDT Practice Model. Every choice that is made before, during, and after a session has the potential to either lead the client and therapist toward this outcome or, when in a random direction, away from this outcome. A session outcome is determined for each intervention session. Just as the long- and short-term outcomes described in the previous chapter include specific, measurable functional outcomes, so too does this session outcome. The paraphrase by Lewis Carroll, “If you don’t know where you are going, any road will get you there,”2 is as applicable to a single session as it is when discussing intervention as a long-term process. The session outcome forms the foundation from which the session is planned, designed, implemented, and evaluated. It is an independent, stand-alone measure of performance for the client. The session outcome provides a frame of reference, an expectation of what is to be achieved during the therapy session. Work within an intervention session sets the stage for motor learning. The reader is directed to Chapters 12 and 13 on motor learning and motor control for further discussion. Session outcomes are generally linked to short-term outcomes (STOs) and long-term outcomes (LTOs). However, the relationship of the session outcome to the STO and LTO is more complex than a simple scaling up of a task or a change in the context of the task. Session outcomes represent desired functions or reflect unique, individual task specific skills, which, when combined, achieve a change in functional capabilities that is consistent with achievement of an STO or LTO. Generally, the relationship of session outcomes to STOs and LTOs is not simply incremental or proportionate. Therefore, a session outcome is not simply written as 25% or 50% of the desired task or linked STO. It is also not constructed as an approximation or extension of the last session’s outcome or linked STO, such as a progression of functional mobility from 5 feet to 10 feet. Again, the session outcome is a stand-alone performance measure of a task. The session outcome is often a subtask or a sister task of an activity that is meaningful to the individual and offers the client and therapist a focused target to address some specific impairments within that session. A sister task is a task that requires the integration of many of the same body systems and/or movement components for task completion. For example, in Case Report A1 in Unit V, the client wanted to return to golf. One of the subtasks of golf is bending down to place the tee in the ground for the ball. A sister task to this task would be bending down to tie his shoes or pick up his towel from the bathroom floor. As discussed in Chapter 8 on the evaluation and plan of care, the session outcome is developed from collaboration among the client, family/caregivers, and therapist. When session outcomes are collectively viewed during an episode of care, they should reveal a sequential pathway for progress toward the STOs and LTOs. When this pathway is established, the client and therapist anticipate that the session outcome will be achieved within the session—that the new task or function is realistic and possible. In the case report on Mark in Unit V, examples of STOs for the occupational therapy and physical therapy sessions show a progression toward the client’s long-term goals of returning to golf and participating in a cross-country move. His individual session outcomes were subtasks or sister tasks of the many activities required for these participations. For example, one session outcome may have been related to how Mark moved into a squat position while reaching for an empty moving box on a lower shelf as seen in Fig. 9.3. Another might be related to how Mark reached back and up behind him with his right hand to get his golf hat from a shelf, a movement similar to what he would use in a golf back swing. For a child who has a long-term outcome of putting on his own jacket at recess time, a session outcome may be how he puts on an art smock for finger painting or how he reaches to select particular toys from shelves to his right and left at shoulder heights. Once a session outcome begins to take shape (it may still be refined), the therapist identifies the constraints and facilitators of the environment and other contexts under which the function will be performed. This identification may occur through discussion with the client and family. For example, the therapist might ask the client to describe the location of the dishwasher relative to the storage area for dishes, cups, and silverware or where his favorite toys are in his room to determine the setup required for practice. This environmental information allows the therapist to make calculated choices about how the intervention practice can be set up. What postures or transitions will be chosen? What will the role of the more involved limbs be in the task practice? Where does the therapist need to be in relation to the client and the tools of the task? What handling should be used to both encourage (facilitate) the efficient movement components that need to be practiced and to limit (inhibit) the inefficient postures and/or movements that are interfering with function? Fig. 9.3 One of Mark’s session outcomes—bending down for a box in preparation for his cross-country move. Establishing a meaningful and achievable session outcome can be motivating and empowering to clients and families because it validates their efforts within and between intervention sessions and provides a definable structure for all to remain focused on. This task practice within the functional context, in the meaningful activity within the intervention session(s), demonstrates to the individual that positive change and success are possible for new and regained skills and that further contextual practice is necessary for this success. A child who practices climbing into the family vehicle after an outpatient session that included stepping up a variety of high steps within the session is not only more likely to be able to get into the family car but also more likely to try the steps of the school bus and perhaps the steps on the slide on the school playground. If an individual is loading or unloading the clothes dryer within the intervention session, as seen in Fig. 9.4, she develops the motor habit, confidence, and skill to repeat this practice at home. The NDT assumption is that, if practice in the session only includes working to increase lower extremity strength and mobility, trunk rotation, and visual scanning, all outside the context of functional activity, the long-term benefit is diminished. The reader is directed to Chapters 12 and 13 on motor control and motor learning for further discussion of these concepts. A common question of novice clinicians is often, “How do I help my clients achieve carryover?” When an individual is practicing functional tasks or subtasks in therapy, the motor and sensory memories and habit of this practice are more likely to carry over into everyday life practice when compared with the performance of movement activities that are more exercise-like and nonfunctionally contextual in nature. Carryover outside of therapy is seldom achieved if the individual is only performing non-contextual exercises in therapy, even if these may be addressing the impairments that interfere with skills, such as unloading the clothes dryer or climbing into the family vehicle. In addition, when immediate suggestions are provided to the individual on how to integrate skills introduced in therapy into the daily routine, the opportunities for direct carryover are increased. Fig. 9.4 As this woman practices loading and unloading the clothes dryer, she incorporates her right upper extremity (UE) into the base of support for her posture and movement. This activity is practiced in context with the therapist monitoring her entire body’s posture and movement skills, working to gain right UE function in context. The outcome may be her ability to do her laundry, whereas the intervention includes increased activity in the right UE in her best alignment. For some individuals, progress is rapid, and significant changes are apparent. For others, progress is slow, and change may be difficult to detect. For clients with progressive, degenerative, or complex and long-term disabilities, success may be measured by little or no loss of function. As discussed in Chapter 15 on neuroplasticity and recovery, an individual’s rate of change may be variable. As discussed in Chapter 8 on evaluation and plan of care, it is of critical importance that the therapist considers all factors that may influence an individual’s potential for change. The session outcome is therefore developed based on the individual’s prognosis and potential for change. The therapist integrates all information obtained about and from the client to set a session outcome that challenges the client yet does not create impossible demands. As the intervention session begins and progresses, the therapist constantly asks, “Is my client working in ways that promote change and progress in all domains of function? Are the demands on all body systems too easy, sufficient, or too demanding? Am I encountering difficulties that I did not originally anticipate? How can I adjust the work we are doing to create challenges that promote progress?” The most successful plan is one that is expected to change constantly. The first part of the session plan includes selecting an activity that can be used as meaningful and motivating practice throughout the session. In some cases, this activity is the client’s outcome activity, and in other cases, it is a simulation or therapeutic activity for the session. For a child, the activity might include pretending to be a princess getting ready to go to a party. For an adult, the selected activity may be working in the woodworking shop to make a gift for a grandchild. The individual may still be functioning at a very low level, and the full task of dressing like a princess or building a wooden toy for a grandchild may not be even remotely possible. However, working within the context of these activities, even at a basic level, will inherently motivate the client. Even if the client is still in an acute care setting after her stroke, having a piece of wood available at the bedside to sand, measure, or examine for defects in the grain will engage her in a way that working with cones or pegs never will. Through activity analysis, the therapist next needs to choose the appropriate subtask or task components of this activity to be practiced within the session that best address the individual’s impairments. Activity analysis includes task analysis, determining the subtasks that make up a task, as well as movement analysis and determining the movement components (sensory, motor, visual, etc.) of the tasks and subtasks. The clinician refers to the plan of care for information regarding STOs, LTOs, and the general plan of care. However, for each session, the clinician creates a plan specific to the session outcome. The clinician identifies the body system integrities, contextual facilitators, and engaging activities that will assist the client in reaching the session outcome. In addition, the clinician identifies and prioritizes which impairments or barriers prevent the achievement of the outcome. For example, if the desired outcome is for the child to put on a sweater while seated on the edge of the bed, it may not be critical that the child has limited hip extension range. For this session, the focus will be on the achievement of this one outcome and the integrities, impairments, facilitators, and barriers that will influence achievement in this one session. An expert clinician may be able to complete this process during the pretest process, whereas a student or novice clinician may need to analyze the task prior to a session and write a plan that outlines the intervention session with specific prioritized impairments that will be addressed in the chosen activities. Eventually, this type of problem solving must be an ongoing and automatic process for effective intervention. An example of this type of analysis and problem solving is developed in the case report about Mark in Unit V. The first table in that case report outlines the standard performance criteria and compares this with Mark’s baseline performance criteria for the task of stooping to pick up a lightweight box off the floor with both upper extremities (UEs), carrying it to a nearby counter top, and placing it on that surface. From this analysis, Mark’s therapist was able to identify his system integrities (facilitators) and prioritize his system impairments interfering with his ability to perform this task. This analysis allowed her to develop a sequence of activities in a single session and sessions over time to address Mark’s impairments in intervention and to move toward a more standard performance of this task. When the therapist identifies the highest priority impairments that interfere with outcome achievement, a list of objectives for changes in the impairments may be generated. These objectives must also be prioritized as to the impairments that must be addressed first in the session and the ones that may be less significant to that session’s outcome. The clinician develops this list but must be willing to constantly reevaluate the decisions and shift intervention based on the changing needs of the client. For the previous examples, the subtask chosen for the session outcome for the child pretending to be a princess might be reaching for the tiara, jewelry, wand, and boa that are in front and slightly above the child. For the adult interested in making a gift for a grandchild in her woodworking shop, the subtask chosen on a given day may be sanding the wood that will be used for the toy baby cradle. When a child or adult is asked at the end of a successful session to report what was done in therapy, the answer may include a description of play activities, task activities, therapeutic activities, or contextual factors, whereas the therapist may answer with the list of impairments addressed and outcomes achieved. Regardless of the perceptions, the appropriate selection of the activity is necessary for a successful session. Once the analysis and planning for the session have been completed, the therapist is ready for the session itself. The structure of sessions may vary depending on the needs of the client, but the following actions occur in most intervention sessions. The session outcome may have been partially established at the close of the previous session because this is when the therapist has the best image of the client and the interaction of all the domains of functioning. It is also then that the therapist or client may know what would be best to do next. The outcome may need to be modified at the start of the session, however, because there may have been changes in the client’s status between sessions. Once the session outcome has been determined and refined, it is important to start each session with a pretest of this outcome. It is possible that an outcome which was thought to be challenging is easily achieved at the start of the session or that the outcome is out of reach on the day of the intervention session. An outcome that seemed ideal at the end of one session may be inappropriate on another day due to changes in family dynamics, an unexpected illness, or faster improvement than predicted. Therefore, it may be necessary to completely rethink an outcome or modify the measurement of the outcome based on this pretest. The following concepts are all critical aspects of NDT intervention and incorporated to reach the stated outcome. These concepts include environmental setup, preparation, simulation, and practice, as well as achieving carryover. These concepts are not meant to be presented as a linear sequence for intervention and do not reflect completely separate concepts within the intervention process. At times, the concepts overlap or repeat, whereas at other times they flow from one to another. Once the outcome has been established and the plan for the session is determined, it is necessary to set up the environment for maximal success. The options for setup vary with different clients and in different settings. If the session will occur at a clinic or in a hospital, the decision may include issues such as whether the session occurs in the individual’s quiet room or in a department with many other people present. The decision is based on factors such as whether a small private space is required for increased focus or concentration or if a large space is necessary for the activities that are to be practiced. If the session is in the client’s home, similar considerations are made. Will the living room be an appropriate space where there is more room but there is added confusion with the extended family watching a loud TV program? Or could the session occur in the client’s bedroom if it is considered appropriate for nonfamily members to be in it? The therapist must also consider what tools/toys may be necessary to complete the task. These items not only include those needed for the activity identified as the outcome but all of the items that may be used throughout the session in both preparatory practice and task practice. For example, it may be necessary to have the appropriate walker close by for an individual if the outcome is related to walking across the room and the individual requires an assistive device, or to have several differently shaped items available, such as a hair brush, toy bat, or cylindrical musical instrument, if grasp is being addressed in therapy with a child. Although each of these items may differ from the exact grasp size required for the outcome task, they can aid in the progression to achievement of the outcome. All of the tools/toys are considered carefully as to the affordances of the object and are not introduced simply because one is readily available in the therapy cupboard or the child really likes a particular toy. For example, if the outcome with a child is to walk with a suspension walker in the home from his bedroom to the kitchen, introducing a new set of tiny Legos that can only be played with in sitting and with pieces that require a pincer grasp is not a wise choice. The toy in this case is a distraction to the achievement of the outcome. Instead, the child may be given a basketball to throw into a hoop while standing with the support of the walker. The therapist (or parent) can encourage the child to walk to the basketball hoop to throw the ball. The ball game is an integral part of the walking experience, as seen in Fig. 9.5. Likewise, a speech-language pathologist (SLP) may have a long-term outcome that an individual will use an augmentative device for communicating at school or in the community. The device may be integrated in each session as the individual makes choices and communicates with the therapist for decision making and conversation and as the therapist and client work together to increase accuracy in icon selection and learning to use the device more effectively. The device is not used as a distraction from the tasks being practiced but is integrated throughout the session. The device may also be incorporated into the occupational therapy and physical therapy sessions as appropriate. The session outcome dictates the furniture, floor surfaces, presence of distractions, and task tools that will be used. Thought and planning must be given to the environmental setup to optimize outcomes. As seen in Fig. 9.6, setting up the environment for an individual who is interested in painting must consider his impairments as choices are made about the posture he is in for the task, where the paint brushes and paint are located, and where he will do the painting. Similarly, as seen in Fig. 9.7, if the individual is a carpenter, choosing the tools, posture, and subtasks to match the impairments will optimize outcomes. In addition to real-life objects, furniture, and tools, therapeutic equipment may also be integrated into the session. The therapist might decide to use a partial body-weight-bearing (PBWB) support device. This decision may be made to allow walking practice in upright alignment with support to free up the therapist’s hands to address impairments such as range limitations or impaired sequencing of muscle activation during the gait process. The therapy equipment must be specifically selected to meet the contextual factors, the outcome, and the impairments. A therapist working in a hospital setting may include the PBWB device because it is readily available while the home-based clinician may not have the same options. A more detailed discussion of the use of therapeutic equipment and assistive technology during intervention and as it relates to home programming is included later in this chapter. An important role of the therapist is to integrate or weave together the preparation of all of the different body structures and functions with activities to keep the client engaged and actively learning. When the therapist is addressing these issues or progressing through the session, the role of handling becomes evident. Handling is an important element of NDT practice that can be used to address any of the domains of the ICF model. The therapist can choose to assist, to resist, to guide, to reinforce, or to limit all or any part of a participation or activity. In addition, any of the single body system impairments or functions can be affected through the handling. The therapist may contact the client with the intent of changing, altering, or modulating one or multiple elements of a task, how the task is being performed, and the impairments in the body system(s) the therapist thinks are contributing to the activity limitation. This process of planning not only involves deciding if therapeutic handling should be used but extends to the questions of when, for what purpose, how, where, and for how long. Within the NDT framework of practice, where the therapist places his hands is referred to as a key point of control (KPC). The key points can include the therapist’s hands on the individual but can also include any avenue of contact. A baby sitting on the therapist’s lap can be given input from the therapist’s thighs underneath her or the arm that the upper body is resting on. Another example is demonstrated in Fig. 9.8. In this case, the therapist uses her leg to provide input to the child’s hip to help the child have confidence to shift weight to the right as the clinician uses her hands to facilitate trunk rotation. The concept of KPCs can be expanded to include concepts such as the visual input of the therapist’s body. KPCs can be unilateral or bilateral, proximal or distal, symmetrical or asymmetrical. Equally important to the consideration of the KPC is the therapist’s rationale for what she believes her hands will provide for the client relative to the learning process. The therapist’s hands should be viewed as a clinical tool; a piece of therapeutic equipment. Their use should be purposeful and judicious. The therapist’s hands can provide minimal tactile cues to guide a movement or can provide deeper proprioceptive information relative to the individual’s alignment, base of support, or need for postural stability or active movement. The input from the therapist’s hands can facilitate stability or movement or can inhibit stability or movement. Often, the therapist’s hands provide both facilitory and inhibitory input simultaneously. Examples of how a clinician may provide handling include assisting the individual to sit up straighter when attempting to put on a T-shirt, assisting an individual who had a stroke with the third rocker action of the more involved stance foot, as seen in Fig. 9.9, or stopping the hand and arm from pulling into flexion when transitioning from sit to stand by facilitating the elbow extensors to actively recruit with the hand placed on a table. The clinician has an anticipated outcome with an anticipated motor performance. Based on the examination and evaluation, there is an expectation of what is going to happen both positively and negatively as the client engages in postures and movements while involved in an activity. Therefore, the therapist introduces specific handling strategies to encourage the desired aspects of the movement needed and to minimize the negative ones. A frequent analogy is made to watching a couple dancing across the floor. The couple interacts through touch and handling to suggest directions or moves to each other. Input may be given to prevent the couple from bumping into another couple (inhibition) or to suggest (facilitate) a more eloquent move when space and time allows. With a client who is experienced in active intervention such as NDT and an experienced clinician, it is possible for the individual to achieve better alignment, posture, balance, and control and coordination of movement for functional outcomes. The effective use of handling requires developing a rapport with a client with the judicious use of facilitation and inhibition, as well as knowing when to grade the client’s withdrawal. Handling should always be temporary and always be given with the intent to give less with each repetition and movement within a session and across sessions over time. Fig. 9.8 The therapist uses her hands on the child’s trunk as a key point of control to facilitate trunk rotation, but her leg becomes the point of contact for the child’s change in weight bearing. Preparation is the process of addressing the impairments in body system structures and functions. Impairments in the individual systems may be addressed one by one or together within multisystem structures and functions, such as posture and movement. An analogy of preparation during intervention is the process of baking a cake. In baking a cake, one must retrieve from the pantry and refrigerator all the ingredients—the flour, the sugar, the chocolate, the eggs, the butter—and mix them together. When working with a client to achieve a desired activity, the therapist needs to help the client access or retrieve the range of motion, the sustained or graded control, the strength, the perceptual awareness of midline, and so on, and blend them cohesively to facilitate an activity. A difference in the two processes is that when the flour is mixed into the cake batter, it stays mixed in. However, the therapist may prepare a system, such as somatosensory awareness in the hand, for transitioning to standing using support of the hands on a support surface. Early in the session, the therapist may have the client use the hand as part of the base of support (BOS) on a coffee table or small stool while squatting to pick an object or toy up from the floor. However, when the transitional task of sit to stand is introduced, the hand may slide off the surface without the client apparently taking notice. The therapist would need to add sensory input during the transition. Therefore, it is often necessary to prepare the body systems throughout the session and even to suggest activities to the client or family that will prepare a system for future sessions. Thus preparation occurs not only at the beginning of the session but throughout the session as the need arises to increase range, reinforce dynamic control in a segment, realign the center of mass (COM) over the base, and so forth. Whenever possible, preparation occurs within functional activities and, at minimum, within functional contexts: movement is organized around the task. Preparation of the following systems within an NDT framework will be discussed: regulatory, sensory, musculoskeletal, neuromuscular, respiratory, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and integumentary. There are certain body systems that may require preparation before others. The order in which the systems are presented here reflects this sequence. In addition, there are clear recommendations from an NDT perspective for how to most effectively prepare a system for achievement of a participation or functional activity outcome. Following the discussion of single-system impairments and intervention, the multisystem impairments are presented. • Regulatory system: If the client has impairment(s) in the regulatory system, it may be necessary to address this system first. If the client is agitated, fearful, or angry, the likelihood that the intervention strategies will have a beneficial outcome is reduced. Quinton3 taught that it is important to respect an infant’s crying and to work to “win” the baby to therapy. If a client is anxious or fearful, it may be necessary to reassure or calm the individual before proceeding. Handling options, such as steady touch or deep pressure, to calm and specific vestibular input to modify the level of alertness may be effective. Environmental modifications, such as lighting, temperature, or noise, are examples of strategies that can be used in intervention to prepare the regulatory system. Life participation usually requires that an individual be able to function in a wide range of contextual factors, such as visual stimulation, noise and other distractions, or an extremely challenging task. Activities in life sometimes need to occur when the individual is nervous or exceedingly excited. Working only in limited or narrow ranges of regulatory control may not lead to maximal change in participation. Thus the individual is gradually exposed to more within and across intervention sessions. • Sensory systems: The second group of impairments to consider addressing early on in intervention is those of the sensory systems. The sensory system is the primary avenue a therapist has to influence a client’s body systems. We access and influence the central nervous system (CNS) and many other body systems via the sensory systems. All of the sensory modalities must be considered as both contributors to activity limitations and facilitators to achieving positive outcomes. Individuals usually have a preferred system that allows them to learn more effectively. It is not uncommon to hear a person report that she is a visual learner or that she needs to feel something before she can perform the activity. The therapist should have a clear idea of the integrity of the individual’s sensory systems as well as impairments in specific sensory modalities. This begins with the examination and evaluation process. The therapist can then choose to use the sensory system integrities in intervention and to address the individual’s impairments. For example, it may be helpful to play classical music in the background for one client, while another may find it irritating. For an individual with an auditory processing impairment, any background music may make it more difficult to attend to verbal directions or feedback. During NDT intervention, it is optimal to provide sensory input in functional contexts rather than out of context. For example, if a therapist wants to improve an individual’s sensory awareness on the sole of the foot, the therapist is more likely to have success with the client standing barefooted on an indoor/outdoor carpeting surface or on a sandy beach than to suggest rubbing an assortment of different textures across the bottom of the foot each day. Intervention for the sensory systems may include addressing the single systems individually such as the visual, auditory, gustatory, or somatosensory systems, or it can include addressing the more complex multisystem phenomena. The therapist must consider the specific roles of the sensory systems on posture and movement. For example, although postural control is influenced by all systems, the visual, vestibular, and somatosensory systems are of prime importance. There is a growing literature that demonstrates, especially in young children, a heavy reliance on the visual system for upright orientation.4,5,6 The influence of the perception of the visual horizon and ambient vision may dramatically influence the performance of the individual as related to head and trunk control and therefore of a task. If the client has an outcome that is impaired because of poor postural control, it is important to address any sensory system impairments that influence the poor postural control for a task. We know that the body structures and systems do not work in isolation but function as a cohesive whole. We also know that most, if not all, activities have a sensory component. Thus it is the responsibility of all clinicians to examine and integrate intervention for multiple systems into the plan of care within their scope of practice, addressing impairments that contribute to clients’ activity limitations. For a more detailed discussion of the sensory and perceptual systems, see Chapter 7 on examination. For intervention strategies for impairments in these systems, the reader is directed to Chapter 16 on occupational therapy as well as the case reports in Unit V. • Musculoskeletal system: The third system to consider addressing initially is the musculoskeletal system and, specifically, that of joint mobility and soft tissue extensibility. If an individual does not have the range to open his mouth more than one finger width, it is unlikely he will be able to bite through a hamburger, or if an individual does not have the range to dorsiflex the ankle to 90° with the knee fully extended, it is unlikely that she will walk with the foot flat and the knee extended at normal speeds. Within the NDT approach, there are specific assumptions concerning how best to achieve functional range of motion for activities. First, it is necessary to understand exactly which body structures are contributing to the lack of mobility. Is it the length of the muscle, tendon, ligaments, or fascia, or is it a bony deformity limiting free motion? Then, just as with all systems, it is optimal to address the impairment within functional contexts. For example, if it is determined that the limitation is in the gastrocnemius/soleus muscle group, the therapist may position the individual in sitting with the foot stabilized at the talus or calcaneus and facilitate a transition from sit to stand with a forward weight shift, thus moving the ankle into greater dorsiflexion, at first with knee flexion for liftoff, followed by knee extension to continue to standing. The individual’s body weight and active muscle contractions aid in the elongation of the shortened muscle group. In Fig. 9.10, the therapists use the individual’s body weight to gain length. In addition, the client and family are instructed in how to position the foot during transfers at home to provide this type of active stretch throughout the day. The therapist may also suggest that the client wear a brace or splint to align the joint at specific times during the day or a device during sleep rather than having the ankle remain in a position of plan-tar flexion. Active elongation or active stretching is preferred rather than passively moving the targeted joint through the range. Strength or force production is a second component of the musculoskeletal system. The Bobaths7 initially claimed that the primary impairment in stroke and cerebral palsy is not weakness but atypical tone. However, working with children post–selective rhizotomy, which alters muscle tone, has taught us that muscle weakness is a factor that can indeed limit activity and participation. When an individual has impairments in force production in muscle(s), the therapist incorporates strengthening strategies into the intervention sessions within functional contexts and activities to reach the desired outcomes. For example, the young child may be unable to drink from her favorite 8 oz glass bottle compared with a 4 oz plastic bottle secondary to weakness in her trunk or arm muscles. Rather than using a standardized exercise, such as a strengthening protocol by adding weights (resistance) to the child’s arm, the therapist would progress functional tasks that gradually demand and build greater strength. Practicing within functional tasks also allows for more efficient strengthening of the postural stabilizers while allowing the mover muscles to do their job and work through the available range that will also actively elongate them when needed.8,9 For play, the child could be presented toys that gradually have increased weight while the clinician ensures that body segment alignment is optimal and postural musculature is optimally active. Play may be progressed from playing with bubbles or light-weight plastic keys on a ring, to playing with toys that are heavier, such as the metal Tonka trucks. The parent may be able to graduate the amount of milk in a bottle (i.e., first the 4 oz bottle and then the 8 oz bottle) to strengthen the child’s trunk and arm muscles. The parent may be encouraged to play tug of war games with the child’s favorite toys and grade the challenge. Fig. 9.10 The therapist holds a more optimal alignment while the client actively loads his body weight over the foot to gain length in the gastrocnemius–soleus muscle group. • Neuromuscular system: The Bobaths10 began the NDT approach based on their belief and experience that it was possible to change muscle tone. Mrs. Bobath10 stated that “the distribution of spasticity is not permanently restricted to certain muscle groups, but influenced, among other factors, by the position of the body in space, the relative position of the head to the body and by the position of the limbs in relation to the body.”10 As discussed in the chapter on examination, the words tone, muscle tone, and postural tone have all been defined and used in a wide variety of fashions. Postural tone is the term being used in this text to refer to a multisystem characteristic, whereas muscle tone refers to the neuromuscular components at the level of the muscle. Strategies to address the impairments of the neuromuscular components of tone will be outlined. Descriptions of each component and the underlying rationales for these strategies are included in Chapter 4 on a model for posture and movement, in Chapter 7 on examination, in Chapters 10 and 11 on cerebral palsy and stroke, and in Chapter 12 on motor control. Another dimension to consider in motor unit recruitment is the ability to sustain a muscle contraction across time. An individual may be able to contract a muscle for a brief moment but is unable to sustain the contraction for sufficient periods of time as may be required for a particular task. If the clinician is attempting to facilitate a sustained motor output, the sensory input is more likely to be lower in intensity, the input is sustained for longer periods of time, and the task choices for practice require a longer duration of muscle recruitment. For example, the therapist may, in a soft steady voice, ask the child to c-a-r-e-f-u-l-l-y hold the cup of juice rather than loudly and abruptly encourage the child to hit a toy drum, or the therapist may ask an adult client to pour the entire watering can into the planter versus just touching the plant leaf. As seen in Fig. 9.11, the child is asked to wipe the whole mirror rather than taking quick swipes with the paper towel. This task requires the shoulder girdle and arm to sustain the pattern of coactivation. As discussed in Chapter 4 on the model of posture and movement and the chapters on motor control and examination, individuals with neuromuscular impairments may have selected impairments of recruitment of either the postural or the phasic motor units. Almost all clients with CNS dysfunction go through a period of decreased ability to recruit the postural motor units. This episode may last for a short time or may extend for years. It may be evident in one body segment, such as the trunk, while being less obvious in the extremities. If a client is unable to recruit the postural motor units, an effective intervention strategy is to facilitate isometric holding of the impaired muscle(s) in a shortened range and to sustain this contraction for as long as is required for the activity. Because α motor neurons that innervate muscles with primarily slow twitch (postural) fibers are recruited first in muscle contractions in many human postures and movements, lower intensity input is suggested.14 It is more important to sustain this isometric contraction during an activity rather than having the individual repeat repetitions of shorter burst contractions. A child could be facilitated to sit tall to draw a picture on an easel in front and slightly above him rather than sitting and reaching to the floor and returning to sitting 10 times in a row. An adult client may be positioned in a high sitting position in the bathroom in front of a mirror that is at least at shoulder height or slightly higher while she combs her long hair versus doing situps. Fig. 9.11 The child is encouraged to clean the entire mirror while maintaining the step position to work on sustained contraction of both the upper and the lower extremities. If the client has an impaired ability to recruit the phasic motor units, it is recommended to start with the muscle in a lengthened position and challenge it concentrically through the entire range followed by movements that require the muscles to recruit fast and alternate between the agonist and antagonist activity. The child could throw a Nerf football at a target across the room or an adult could swing a golf club through a full back and foreswing arc. If the client is compensating for a postural deficit with overrecruitment of the phasic motor units, the postural motor units must be strengthened while the therapist engages the phasic motor units in activities. For example, the child may be holding a toy with both hands that, when shaken, makes a musical sound. Holding this object, even if it is relatively light in weight, requires sustained postural muscle activation while the phasic motor units in the limbs are recruited in a fast and reciprocating way as he shakes the toy. The challenge is that every task has elements that require postural holding and elements that require quick or phasic movement.15 The clinician must weave these elements together at the right time and in the right place for the client to achieve the desired outcome. The principles for selective recruitment of postural, sustaining motor units versus the phasic, movement motor units are presented in greater depth in the chapter on the posture and movement model by Stockmeyer. Clinical examples are presented in the case reports in Unit V. For these impairments, the clinician may choose practice activities and tools/objects that facilitate grading of muscle recruitment rather than requiring maximal contractions or sustained coactivation of muscles. For example, if an individual is unable to effectively grade the recruitment of quadriceps and hamstring activity in his legs, choosing a task such as that shown in Fig. 9.12a, b would be preferred over sustaining a standing posture while writing on a chalkboard.

9.1 Intervention Using the Neuro-Developmental Treatment Practice Model

9.1.1 Components of an Intervention Session

The Client, Family, and Therapist Roles in Intervention

Setting Session Outcomes

Activity Analysis

The Intervention Session

Pretest of Functional Outcome

The Interaction of the Client, Family, Therapist, and Environment during the Session

Initial Environmental Setup

Handling

Preparation

Single-System Preparation

Motor unit recruitment: The simplest functional unit of the peripheral nervous system is the motor unit.11 The motor unit includes an α motor neuron and the muscle fibers it innervates. The basic law of operation of a motor unit is an all or none principle; the motor unit either reaches the threshold, and the neuron fires and the muscle fibers contract, or the threshold is not reached, and there is no muscle contraction. These basic descriptions of neural recruitment form the foundation to describe neuromuscular impairments and to develop intervention strategies. Studies have documented that, following a cortical lesion, the CNS lesion loses its ability to modulate firing frequencies during voluntary movement.12,13 The clinician knows from a foundation in neurophysiology that to increase the likelihood of any motor neuron reaching its threshold, two neural mechanisms can be incorporated. Those mechanisms are spatial and temporal summation. In temporal summation, depolarization occurs and the motor neuron fires because synaptic potentials occur close together in time; a single input is not sufficient. Likewise, a motor neuron may receive excitatory inputs from different interneurons at approximately the same time that can lead to spatial summation. A therapist, therefore, can theoretically influence the types or intensities of sensory inputs to increase the likelihood of firing through handling. These inputs include using tension and/or directional information over muscles and joints through skin and/or adding compression or approximation through optimally aligned joints. To decrease the likelihood of firing, the clinician can increase the types, intensity, and frequency of inhibitory inputs with handling strategies, such as by providing firm, sustaining, deep pressures into the muscle belly or at its origin or insertion or through manual vibration.

Motor unit recruitment: The simplest functional unit of the peripheral nervous system is the motor unit.11 The motor unit includes an α motor neuron and the muscle fibers it innervates. The basic law of operation of a motor unit is an all or none principle; the motor unit either reaches the threshold, and the neuron fires and the muscle fibers contract, or the threshold is not reached, and there is no muscle contraction. These basic descriptions of neural recruitment form the foundation to describe neuromuscular impairments and to develop intervention strategies. Studies have documented that, following a cortical lesion, the CNS lesion loses its ability to modulate firing frequencies during voluntary movement.12,13 The clinician knows from a foundation in neurophysiology that to increase the likelihood of any motor neuron reaching its threshold, two neural mechanisms can be incorporated. Those mechanisms are spatial and temporal summation. In temporal summation, depolarization occurs and the motor neuron fires because synaptic potentials occur close together in time; a single input is not sufficient. Likewise, a motor neuron may receive excitatory inputs from different interneurons at approximately the same time that can lead to spatial summation. A therapist, therefore, can theoretically influence the types or intensities of sensory inputs to increase the likelihood of firing through handling. These inputs include using tension and/or directional information over muscles and joints through skin and/or adding compression or approximation through optimally aligned joints. To decrease the likelihood of firing, the clinician can increase the types, intensity, and frequency of inhibitory inputs with handling strategies, such as by providing firm, sustaining, deep pressures into the muscle belly or at its origin or insertion or through manual vibration.

Concentric, isometric, or eccentric muscle contractions: It is not sufficient to determine only if a muscle is able to contract. To understand the control or coordination of muscles, one must also consider the type of muscle contraction required for the task since every task requires a specific series of muscle contractions. Task analysis should identify not only what muscles need to be active or inactive at a particular time but also how that activity should occur—concentrically, isometrically, or eccentrically. Activities in the intervention session should specifically be chosen to target these contractions: the right type at the right time in the activity/movement. For example, if a child has difficulty controlling eccentric lower extremity (LE) extensor muscle activity, working on descending stairs or getting to the floor to play with his toys will be chosen over climbing the stairs or hopping and jumping to music. If a client has a Trendelenburg gait secondary to impaired isometric control of the hip abductors, working on sustained isometric holding on the stance leg in standing activities, such as stepping up on a step or the ledge of the bathtub with the other leg, will be chosen over strengthening the muscle concentrically with lateral leg lifts in standing or with leg lifts in side lying.

Concentric, isometric, or eccentric muscle contractions: It is not sufficient to determine only if a muscle is able to contract. To understand the control or coordination of muscles, one must also consider the type of muscle contraction required for the task since every task requires a specific series of muscle contractions. Task analysis should identify not only what muscles need to be active or inactive at a particular time but also how that activity should occur—concentrically, isometrically, or eccentrically. Activities in the intervention session should specifically be chosen to target these contractions: the right type at the right time in the activity/movement. For example, if a child has difficulty controlling eccentric lower extremity (LE) extensor muscle activity, working on descending stairs or getting to the floor to play with his toys will be chosen over climbing the stairs or hopping and jumping to music. If a client has a Trendelenburg gait secondary to impaired isometric control of the hip abductors, working on sustained isometric holding on the stance leg in standing activities, such as stepping up on a step or the ledge of the bathtub with the other leg, will be chosen over strengthening the muscle concentrically with lateral leg lifts in standing or with leg lifts in side lying.

Gradation: There are also impairments in motor unit recruitment that affect the ability of muscles to grade activity; within a muscle, between agonist and antagonist, and/or among multiple muscles in a limb or between body segments. As discussed in Chapter 7 on examination, this gradation relies on the interplay between reciprocal activation and coactivation. For example, if an individual is unable to effectively grade the recruitment of quadriceps and hamstring activity in his leg for stability in stance, the therapist could choose a task such as reciprocally ascending and descending stairs as opposed to sustaining a standing posture while brushing his teeth. Handling is also used to limit errors in performance, such as facilitating eccentric hip and knee extensor activity to prevent dropping to the lower step in an uncontrolled way while descending or by facilitating hip extension to neutral before the knee extends fully to prevent a hyperextending knee while ascending stairs. If the need is for stability with greater coactivation, the therapist can provide approximation through an optimally aligned knee during stance in a standing task. If the greater impairment is thought to be diminished reciprocal activation of the quadriceps and hamstrings, the therapist could provide light resistance to the trailing leg as it begins to lift up to the higher tread. What makes any of these strategies NDT-based is not the specific technique (many clinicians use compressions or approximation during intervention without it being NDT), it is the ongoing examination with the clinical problem solving that relates impairments to the individual’s activity and participation domains, the decisions to incorporate any specific strategy into the functional activity context, and the active participation of the client in the problem-solving process.

Gradation: There are also impairments in motor unit recruitment that affect the ability of muscles to grade activity; within a muscle, between agonist and antagonist, and/or among multiple muscles in a limb or between body segments. As discussed in Chapter 7 on examination, this gradation relies on the interplay between reciprocal activation and coactivation. For example, if an individual is unable to effectively grade the recruitment of quadriceps and hamstring activity in his leg for stability in stance, the therapist could choose a task such as reciprocally ascending and descending stairs as opposed to sustaining a standing posture while brushing his teeth. Handling is also used to limit errors in performance, such as facilitating eccentric hip and knee extensor activity to prevent dropping to the lower step in an uncontrolled way while descending or by facilitating hip extension to neutral before the knee extends fully to prevent a hyperextending knee while ascending stairs. If the need is for stability with greater coactivation, the therapist can provide approximation through an optimally aligned knee during stance in a standing task. If the greater impairment is thought to be diminished reciprocal activation of the quadriceps and hamstrings, the therapist could provide light resistance to the trailing leg as it begins to lift up to the higher tread. What makes any of these strategies NDT-based is not the specific technique (many clinicians use compressions or approximation during intervention without it being NDT), it is the ongoing examination with the clinical problem solving that relates impairments to the individual’s activity and participation domains, the decisions to incorporate any specific strategy into the functional activity context, and the active participation of the client in the problem-solving process.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree