INTRODUCTION

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) was first described by von Recklinghausen in 1863. In 1880, Bourneville coined the term sclérose tubéreuse for the potato-like lesions in the brain. In 1890, Pringle described the facial nevi or adenoma sebaceum. Vogt later emphasized the classic triad of seizures, intellectual disability, and adenoma sebaceum. TSC (MIM 191400) is a progressive genetic disorder characterized by the development in early life of hamartomas, malformations, and congenital tumors of the CNS, skin, and viscera.

PATHOLOGY AND PATHOBIOLOGY

The pathologic changes are widespread and include lesions in the nervous system, skin, bones, retina, kidney, lungs, and other viscera. Multiple small nodules often line the ventricles.

TSC is characterized by the presence of hamartias and hamartomas. Hamartias (from the Greek for “flaw”) are malformations in which cells native to a tissue display abnormal architecture and morphology. These lesions do not grow disproportionately for the tissue or organ in which they are found. Hamartomas have the same characteristics but grow excessively for their site of origin. This old concept is valuable in recognizing the proliferative potential of lesions found in TSC. Thus, cortical tubers are hamartias and do not grow excessively, whereas angiomyolipomas are hamartomas that grow disproportionately and may produce symptoms as a consequence.

The brain is usually normal in size, but variable numbers of hard nodules occur on the surface of the cortex. These nodules are smooth, round, or polygonal and project slightly above the surface of the neighboring cortex. They are white, firm to the touch, and of various sizes. Some involve only a small portion of one convolution; others encompass the convolutions of one whole lobe or a major portion of a hemisphere. In addition, there may be developmental anomalies of the cortical convolutions in the form of pachygyria or microgyria. On sectioning of the hemispheres, sclerotic nodules may be found in the subcortical gray matter, the white matter, and the basal ganglia. The lining of the lateral ventricles is frequently the site of numerous small nodules that project into the ventricular cavity. Sclerotic nodules are less frequently found in the cerebellum. The brain stem and spinal cord are rarely involved.

Histologically, the nodules are characterized by a cluster of atypical glial cells in the center and giant cells in the periphery. Calcifications are relatively frequent. Other features include heterotopia, vascular hyperplasia (sometimes with actual angiomatous malformations), disturbances in the cortical architecture, and, occasionally, development of subependymal giant cell astrocytomas (SEGAs). Intracranial giant aneurysm and arterial ectasia are uncommon findings.

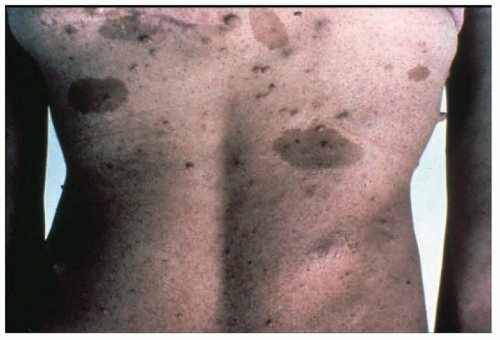

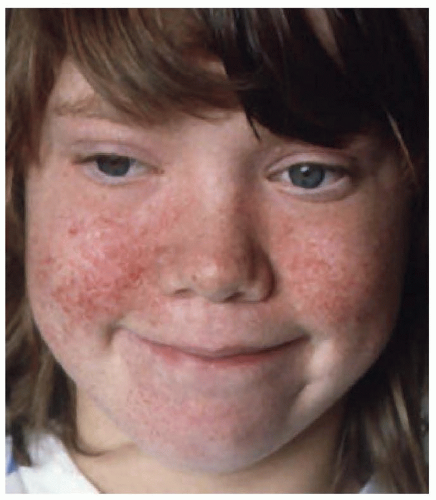

The skin lesions are multiform and include the characteristic facial angiofibromas and fibrous plaques, typically localized to the frontal area. The facial lesions are not adenomas of the sebaceous glands but small hamartomas arising from nerve elements of the skin combined with hyperplasia of connective tissue and blood vessels (angiofibromas) (

Fig. 140.4). In late childhood, lesions similar to those on the face are found around or underneath the nails (

periungual or

subungual fibromas). Circumscribed areas of

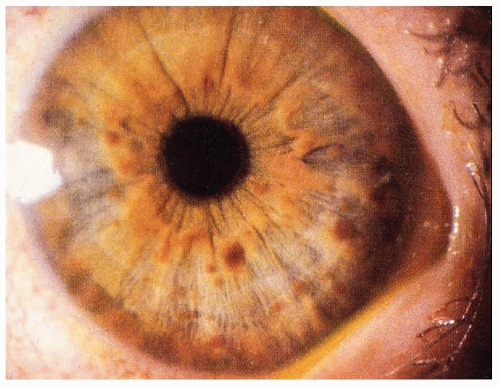

hypomelanosis or depigmented nevi are common in tuberous sclerosis and are often found in infants. Although these depigmented nevi are less specific than the angiofibromas, they are important signals of the diagnosis in infants with seizures. Histologically, the skin appears normal except for the loss of melanin, but ultrastructural studies show that melanosomes are small and have reduced content of melanin. The retinal lesions are small congenital tumors composed of glia, ganglion cells, or fibroblasts. Glioma of the optic nerve has been reported.

Other lesions include cardiac rhabdomyoma; renal angiomyolipoma, renal cysts, and, rarely, renal carcinoma; cystic disease of the lungs and pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis; hepatic angiomas and hamartomas; skeletal abnormalities with localized areas of osteosclerosis in the calvarium, spine, pelvis, and limbs; cystic defects involving the phalanges; and periosteal new bone formation confined to the metacarpals and metatarsals.