CHAPTER 191 Neuroendoscopy

History

Endoscopic neurosurgery began in the early 20th century as an effort to diagnose and treat hydrocephalus. Surgeons realized that the same instruments used in urologic procedures could be inserted into the cerebral ventricles. In 1910, Victor Darwin Lespinasse, a urologist in Chicago, cauterized the choroid plexus of two infants with hydrocephalus using a rigid cystoscope. The results were not published but were presented locally. One child died immediately; the other lived for 5 years.1 Lespinasse subsequently abandoned the procedure, calling it an “intern’s stunt.”

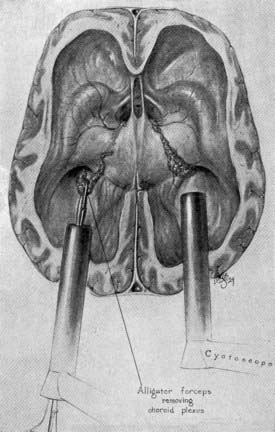

Walter Dandy is considered to be the father of neuroendoscopy. In 1918, he attempted to treat hydrocephalus in four infants by using a thin-bladed nasal speculum to gain access to the ventricles.2 He extirpated the choroid plexus by avulsing it. Only one infant survived. Later in 1922, in a one paragraph landmark article in the Johns Hopkins Hospital Bulletin, Dandy coined the term ventriculoscope and described his use of a rigid cystoscope to gain access to the ventricles and fulgurate the choroid plexus in two hydrocephalic infants.3 Using electrocautery and long-handled scissors, Dandy was able to extirpate the choroid plexus under endoscopic guidance (Fig. 191-1). Subsequently, using similar techniques, he successfully removed choroid plexus tumors in three patients.4

FIGURE 191-1 Dandy’s ventriculoscope. The choroid plexus of the lateral ventricles was removed using two Kelly cystoscopes.

(From Dandy WE. Surgery of the Brain, Hagerstown, MD: WF Prior, 1945:245.)

Although Dandy performed the first third ventriculostomy through an open procedure, it was in 1923 when W. Jason Mixter reported the first successful endoscopic third ventriculostomy (ETV) using a flexible urethroscope.5 The operation was considered a success in that postoperatively indigo carmine dye instilled into the lateral ventricle could be recovered by a needle in the lumbar subarachnoid space. This recovery could not be demonstrated preoperatively, purportedly because of the patient’s noncommunicating hydrocephalus.

For years, the main surgical treatment of hydrocephalus was either ETV or endoscopic coagulation of the choroid plexus. Ultimately, neuroendoscopy fell out of favor because of the high rate of complications related to the primitive nature of the instruments and the advent of successful extracranial ventricular shunting. The first successful ventricular shunt procedure was performed by Frank Nulsen and Eugene Spitz in 1919 and reported in Surgical Forum in 1951.6 Extracranial ventricular shunting revolutionized the treatment of hydrocephalus and quickly became the procedure of choice for treating hydrocephalus.

Instrumentation

There are two classes of neuroendoscopes: rigid and flexible. The modern endoscope would not have been possible without the innovations of a British optical physicist, Harold Hopkins.7 Rigid endoscopes have optics that are superior to flexible fiberoptic endoscopes. Karl Storz adopted the solid rod lens developed by Hopkins and used it in his rigid endoscope systems. Hopkins and Storz developed the SELFOC lens, which is still used in modern rigid endoscopes and is more efficient than earlier lens models.8 The SELFOC lens has a refractive index that varies with the radial dimension of the lens, whereas the conventional lens has a uniform refractive index.8,9 The lens expands the field of vision and eliminates the need for a relay lens while preserving light transmission.8,10 The Hopkins lens system could also be made with a significantly smaller diameter than the earlier, more primitive lenses designed by Nitze for urologic use. Adding a series of angled rod lenses to the 0-degree straightforward lens system enhanced the maneuverability of the instrument.

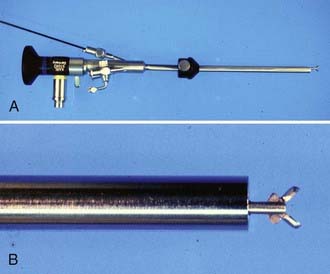

There are devices designed for cutting, grasping, aspirating, and sampling lesions (Fig. 191-2). Balloon catheters and rigid and flexible probes are available for fenestration of cystic lesions, the septum pellucidum, and the floor of the third ventricle. Small catheters introduced through working channels in the endoscope sheath can provide irrigation and suction. It is important to keep the operative field clear by irrigation because even a small amount of blood can impair visualization. It is imperative that there be an escape route for irrigating fluid to prevent ventricular dilation and increased intracranial pressure (ICP) in a closed system.

The energy sources for neuroendoscopic dissection include monopolar and bipolar electrocoagulators and a number of fiberoptic lasers. Two of the most commonly used lasers are the neodymium-doped yttrium-aluminum-garnet (Nd : YAG) laser and the potassium titanyl phosphate (KTP) laser. Nd : YAG lasers emit light that is invisible and require a visible helium neon pilot beam. Pigmented tissues have a preferential absorption of the light emitted by the Nd : YAG laser. Thus, ventricular cyst walls and the whitish septum pellucidum require higher power settings for fenestration. KTP lasers emit a green light and do not require a pilot beam. Other, less commonly used lasers include argon and holmium sources. We have used endoscopic laser dissection for various lesions such as third ventricular colloid cysts, but prefer not to use the laser during ETV for fear of injuring the basilar artery. Oertel and colleagues have shown promising results in selected patients with a water jet system for dissection with preservation of nearby vessels.11

Stereotactic Endoscopy

Both rigid and flexible endoscopes can be used with stereotactic guidance.12–17 Standard frame-based stereotaxy is useful to guide an endoscope to the proximity of a lesion with small ventricles. Visual anatomic clues, once the endoscopist has accessed the ventricle, can further guide the operator in dissecting closer to the lesion. In addition, the frame itself can serve as a mount for the endoscope. However, frame-based endoscopy is not applicable to infants and young children. Frameless stereotaxy defines a three-dimensional coordinate space for a preoperative imaging modality and translates it to the three-dimensional coordinate space of the operative field. Articulated mechanical arms, sonic or optical digitizers, and electromagnetic systems are substituted for the frame (Fig. 191-3).18–21

Endoscopic Anatomic Considerations

After the orientation of the image on the monitor is concordant with the position of the patient, standard intraventricular landmarks are identified.22,23 The foramen of Monro is usually identified first,24 given that it is in line with the trajectory of the ventriculoscope from a coronal approach. The septum pellucidum is located medially, and the head of the caudate nucleus is situated laterally. The choroid plexus is always projected posterior to the foramen of Monro. The posterolateral thalamostriate vein joins the anteromedial septal vein to form the internal cerebral vein. The caliber of these veins increases as they approach the foramen of Monro. A pair of white C-shaped structures, the fornices, are seen as they curve ventrally and inferiorly to define the medial and anterior borders of the foramen of Monro.

Endoscopic Procedures

Endoscopic Third Ventriculostomy

Despite Mixter’s first successful ETV in 1923,5 the procedure did not gain early popularity because of poor illumination, primitive and bulky instruments, inconsistent results, and high complication rates. After the introduction of valve-regulated shunts in the early 1950s, ETV fell out of favor for some time. However, ventricular shunts are troublesome devices and pose lifelong problems for shunted patients. The significant improvement in endoscopic technology in recent decades has led to a renewed interest in ETV.

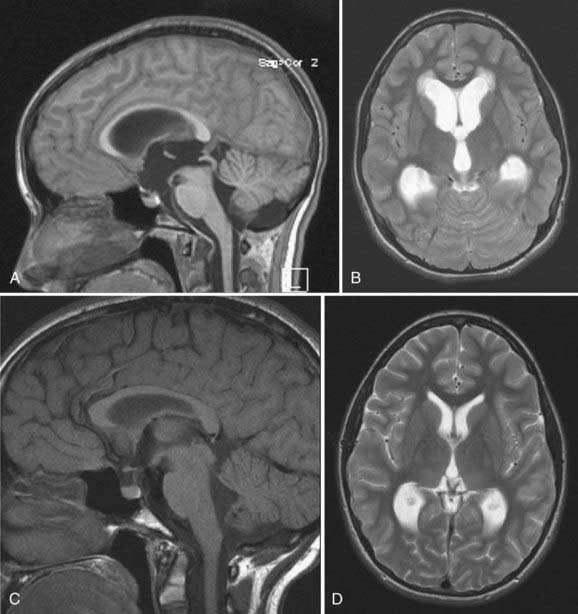

Candidates for ETV should have symptomatic noncommunicating hydrocephalus with a patent subarachnoid space. A classic example is acquired aqueductal stenosis with resulting proximal dilation of lateral and third ventricles. Neuroimaging, in particular magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), is useful in diagnosing noncommunicating hydrocephalus (Fig. 191-4). The ideal candidate for ETV has enlarged lateral and third ventricles, including a third ventricular floor that is thinned and bowed inferiorly. Preoperative planning with MRI delineates the anatomy of the third ventricle and the aqueduct of Sylvius and the location of the basilar artery on the sagittal view.

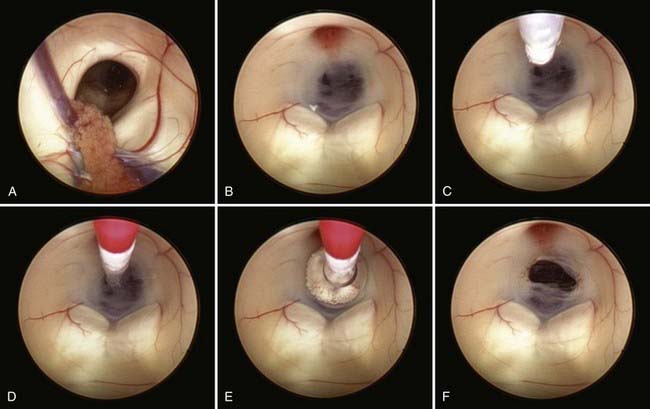

Safe fenestration of the floor of the third ventricle requires the procedure to be performed in the midline and anterior to the mamillary bodies and the underlying basilar artery apex (Fig. 191-5). Fenestration of the floor of the third ventricle can be performed by blunt penetration with the endoscope or a rigid probe, electrocoagulation, balloon catheterization, water jet fenestration, or laser coagulation. Our preference is to use a rigid probe introduced through a working channel in the endoscope sheath to puncture the floor of the third ventricle. A Fogarty balloon catheter with its stylet in place is also an effective means of puncturing the third ventricular floor. The balloon catheter is then repetitively inflated and deflated to widen the fenestration (Fig. 191-6). Both the ependyma and underlying arachnoid are opened. Bleeding from the edges of the opening can be tamponaded by keeping the balloon inflated for a slightly longer period. Fluctuation of the margins of the fenestration indicates cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flow. The basilar artery complex can be visualized through the fenestration without inserting the endoscope into the basal cisterns (Fig. 191-7).

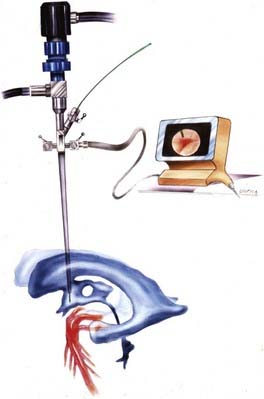

FIGURE 191-5 Endoscopic third ventriculostomy.

(From Cohen AR. Images in clinical medicine. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:552.)

FIGURE 191-7 Endoscopic view of basilar artery in the prepontine cistern after third ventriculostomy.

The reported success rate of ETV ranges from 50% to 95%.25–33 There are conflicting studies that have described the outcome after ETV to be dependent on age,25,26,34–36 independent of age,37,38 or dependant mainly on etiology.28,35,39,40 In a multivariate analysis, Drake and associates reported a higher failure rate for younger patients, particularly neonates and infants.26 Similarly, Kadrian and coworkers have shown a higher failure rate for patients younger than 6 months.25 The procedure is less likely to be successful if there is any history of communicating hydrocephalus.24,41 For example, patients with aqueductal stenosis who have prior evidence of ventricular hemorrhage, shunt infection, or meningitis are less likely to have a good result.36,42,43 However, this is not uniformly the case because ETV has been reported to be successful in some patients with hydrocephalus and associated ventricular shunt infections.44,45 The success of an ETV procedure is determined mainly by clinical evaluation, not postoperative imaging, because the ventricular system may not change significantly in size.

Although ETV is an effective treatment for selected cases of noncommunicating hydrocephalus, it is not without risks. The reported complication rates range from 0% to 20% in different series,46–48 with a mortality rate of less than 1%.30,47,49 Complications can be categorized as intraoperative, early postoperative, and late postoperative. Intraoperative complications include neurovascular injury and bradycardia with cardiac arrest.42,50–54 Massive subarachnoid bleeding from perforation of the basilar artery or its branches has been reported.55–59 The Canadian cooperative study reported a 1.4% bleeding rate in 368 patients who underwent endoscopic ETV.26 Other authors have reported both arterial and venous bleeding during their procedures.28,60–62

Intraoperative hemodynamic changes have been documented in different series. El-Dawlatly and coworkers experienced a 41% rate of intraoperative bradycardia during perforation of the third ventricular floor in their patients.63 A proposed mechanism for intraoperative hemodynamic changes suggests Cushing’s response from elevated ICP from aggressive irrigation and stimulation of the preoptic area or posterior hypothalamus resulting in bradycardia or tachycardia, respectively.64 Handler and associates documented an intraoperative cardiac arrest during ETV in a patient with aqueductal stenosis.52 The patient required cardioversion. This case demonstrates the danger of infusing a high-flow fluid irrigation in a closed system.

Early postoperative complications include subdural hematoma, CSF leak, infection, and endocrinologic disorders. A large corticotomy draining into the subdural space or sudden excessive CSF drainage during ETV is a possible risk factor for the development of subdural hematomas.61,65,66 Restoration of CSF absorption by the arachnoid granulations may not be immediate in the early postoperative period. The increased ICP can lead to the development of a CSF collection under the incision or leakage of CSF resulting in meningitis or ventriculitis. Several investigators have reported electrolyte and endocrinologic abnormalities following ETV.51,67–69 Abnormalities include the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH), diabetes insipidus, and secondary amenorrhea.51,68,69 Other early postoperative complications include transient memory loss and personality disorders from injury to the fornices as well as cranial nerve palsies and seizures.26,33,46,47,54,61,70,71

Late postoperative complications consist mainly of delayed failure from closure of the ETV stoma. The reported rate of delayed failure ranges from 2% to 15% in different series.26,28,72–74 Late failure leading to rapid clinical deterioration and death are rare but real occurrences.48,72,75 The mechanism of ETV failure may be multifactorial. Causes include inadequate size of the initial fenestration, underappreciated secondary membranes, reduced or no CSF flow through the fenestration, narrowing or closure of the stoma due to hemorrhagic obstruction, elevated CSF protein and fibrinogen, postoperative infection with CSF obstruction at the fenestration site or inadequate CSF absorption by the arachnoid granulations, and tumor progression resulting in blockage.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree