CONDITIONS ATTRIBUTED TO HUMAN IMMUNE DEFICIENCY VIRUS INFECTION

A. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder.

1. Epidemiology. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder (HAND) is the impaired cognition caused by HIV; and despite advances in the treatment of HIV with more effective ART, the CNS continues to be affected by this disease. Although the incidence of the most severe form of HAND, HIV-associated dementia (HAD), has declined due to effective ART, the incidence of milder forms of HAND (asymptomatic neurocognitive impairment [ANI] and mild neurocognitive disorder [MND]) remains stable. Even in its mildest form, HAND has been associated with lower medication adherence, decreased ability to perform the most complex daily tasks, difficulty finding employment, worse quality of life, and shorter survival. A recent study employing neurocognitive testing found that 69% of patients with HIV infection taking ART and without detectable plasma HIV VL or cognitive complaints had subtle cognitive impairments. With individuals surviving longer due to effective ART and the independent evolution of HIV in the relatively sequestered CNS, there could be a rise in HAND. Studies have demonstrated discordant presence of HIV VL in CSF despite undetectable plasma viral load and differing HIV viral strains in CSF compared to those found in plasma, which may have different resistance-associated mutations (RAMs) to ART.

In addition to HIV infection itself, several factors may predispose HIV-infected individuals to cognitive impairment, such as concurrent hepatitis C virus infection, the use of psychoactive medications, substance use, mood disorders, low educations, and age-related cognitive changes. ART may alter lipid metabolism with accelerated atherosclerosis increasing the risk of cerebrovascular disease with related cognitive deficits.

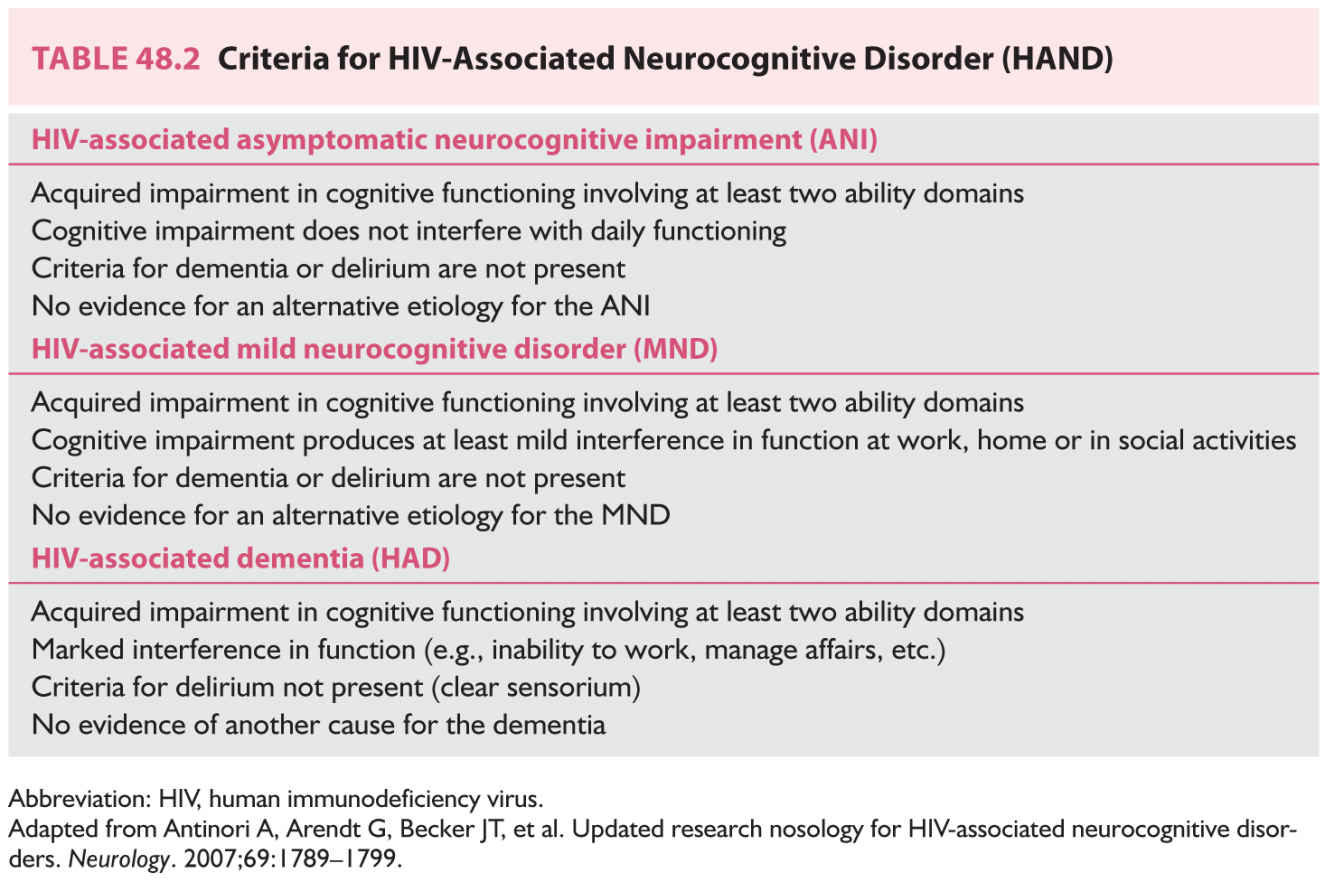

Three categories have been proposed to describe the current spectrum of HAND (Table 48.2):

a. Asymptomatic neurocognitive impairment. Individuals with acquired subclinical impairment in at least two cognitive domains on neurocognitive testing, without delirium, symptomatic complaints, or impaired daily activities.

b. Mild neurocognitive disorder. Individuals with clear sensorium and acquired impairments in at least two cognitive domains causing at least mild interference with daily activities.

c. HIV-associated dementia. Individuals with clear sensorium and more severe acquired impairments in at least two cognitive domains sufficient to produce marked interference with daily activities.

2. Pathogenesis. The pathogenesis of HAND is not well understood. Pre-ART autopsy studies demonstrated multinucleated giant cells containing HIV, myelin pallor, microglial nodules, and loss of neurons and synaptic density. ART era studies have found less significant correlations between the first three elements and clinical impairments. Neurons are not infected by HIV and die in locations remote from the perivascular macrophages and microglia that harbor the virus. Indirect neurotoxicity resulting from soluble factors released by infected cells causing activation of inflammatory mechanisms and disruption of critical trophic influences which culminate in neuronal apoptosis and neuron damage are currently favored as the pathogenesis for HAND.

3. Clinical features. A clinical triad of cognitive impairment, behavioral changes, and motor impairment was described early in the AIDS pandemic. Cognitive features include slowness of thought processing, perseveration, impairments of complex attention, and impaired recall of acquired memories. Behavioral features include apathy, withdrawal from social interaction, and depression. Uncommonly, mania or atypical psychoses occur. Motor features include hyperreflexia, hypertonia, ataxia, and tremors, typically affecting the legs initially but also involving fine motor coordination of the upper extremities. Extrapyramidal features including bradykinesia, facial masking, rigidity, and postural instability may be seen.

In patients on ART, the features may be attenuated and the temporal course prolonged. Psychomotor slowing, lassitude, and mild extrapyramidal or fine motor impairments are most commonly seen. The impact can still be significant both on the more demanding aspects of daily activities and by altering adherence to ART regimens resulting in loss of viral suppression. Individuals may have mild cognitive abnormalities on testing but no apparent changes in daily functioning. Performance fluctuation on cognitive tests is seen in more mildly affected individuals with some improving and others evolving to more severe impairments.

4. Diagnosis. A clear sensorium is required for the diagnosis of HAND. Evidence of functional impairment often comes to attention from impaired work performance or reports from a companion who assumes responsibility for handling funds and documents. Withdrawal from social activities is common, and depression may be a comorbid feature. Neuropsychometric testing should be employed for both diagnosis and monitoring. OIs must be excluded with neuroradiographic imaging and CSF analysis. Other comorbid conditions also need to be evaluated such as metabolic abnormalities, use of psychotropic medications, and the presence of substance abuse.

In patients with HAND, CSF is normal or shows mild-to-moderate protein elevation. Occasionally HIV emerges in the CSF along in the presence of plasma virologic control. This phenomenon of viral escape is uncommon but should be a sign to assess the CSF if new or active neurologic symptoms are present that are not otherwise explained. In the ART era, many patients with asymptomatic or mild impairments are not severely immunosuppressed. Neurocognitive measures are sensitive but must be compared with appropriate normative populations with similar age, educational level, ethnicity, and gender.

MRI in HAND may be normal, demonstrate atrophic changes, or reveal a confluent symmetric leukoencephalopathy. More recent radiologic studies have focused on evaluating the use of newer MRI techniques such as diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) and functional MRI (fMRI). DTI has been shown to be a sensitive tool in detecting white matter changes in various CNS diseases. fMRI makes use of the blood oxygen level dependent contrast to provide dynamic information during resting state or performance of cognitive tasks. Abnormal activation and connectivity have been seen on fMRI among HIV patients with mild cognitive impairment. Studies have demonstrated that functional connections within and between particular networks may be compromised in HAND.

5. Management.

a. Antiviral agents. There are increasing data demonstrating there is variable CSF concentration achieved by antiretrovirals (ARVs). The variable CSF penetration of different ARVs may help explain the discordance in CSF viral escape and paradoxical cognitive deterioration in patients with HAND who have plasma viral suppression. ARVs with greater CNS penetration are thought to be more effective at treating HAND. To address this issue, CNS penetration effectiveness (CPE) was developed and assigns a number to each ARV based on its chemical properties, CSF concentration, and effectiveness at achieving a reduction in CSF VL based on available data. The higher the CPE number, the better the CNS availability and chance of obtaining an undetectable CNS HIV VL. There is no established optimal ART regimen for HAND; however, antiretroviral resistance testing of recovered virus from blood and CSF can aid in the selection of a regimen, ideally one with a higher CPE score and minimal adverse effects. Zidovudine (AZT), a nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI) that penetrates into CSF reasonably well, was the first antiretroviral agent shown in a prospective randomized controlled trial (RCT) to have efficacy in HAND, as measured by serial cognitive testing. ARVs with highest CPE score of four (Zidovudine, Nevaripine, Indinavir) are followed by those with a score of three (Abacavir, Emtricitabine, Efavirenz, Darunavir, Fosamprenavir, Kaletra, Maraviroc, and Raltegravir). Other strategies for treatment of HAND include targeting mediators of neurotoxicity and a searching for reliable and timely surrogate markers of CNS disease.

b. Supportive therapy.

(1) Apathy and withdrawal can be managed with modafenil 200 to 400 mg daily (not an FDA-approved indication) or methylphenidate at 5 to 10 mg two or three times a day.

(2) Depression is usually managed with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) such as fluoxetine or others. Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) such as nortriptyline at initial dosages of 25 mg at bedtime, increasing in 25-mg increments every 1 to 2 weeks (or similar agents at comparable doses) are alternatives; however, anticholinergic effects of these drugs can precipitate delirium.

(3) Seizures occur with increased frequency in HIV-infected patients. Because of potential interactions with ART, non–enzyme-inducing antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), which are not metabolized by the cytochrome P-450 system, such as levetiracetam, lamotrigine, gabapentin, or pregabalin, are preferred.

(4) Supervision. Progression of HIV-associated cognitive change results in loss of ability to manage personal business and financial affairs. Provisions for assistance and ultimately legal transfer of decision-making powers for both financial and healthcare decisions, and advanced healthcare directives, should be arranged. Assistance in the home may be needed for the provision of meals and facilitation of personal care. Residence in a sheltered facility can be considered when the need for assistance precludes independent living.

6. Outcomes. ART has reduced the severity and mortality of HAND. By prolonging survival of patients with HIV infection, ART may also lead to an increase in prevalence of cognitive impairment. The natural history of HAND in the era of successful ART continues to evolve.

1. Epidemiology. This condition is symptomatic in 5% to 10% of patients, although neuropathologic evidence of myelopathy has been found at the time of autopsy in up to 50% of patients with AIDS. In the era of effective ART, the frequency appears to be decreasing.

2. Pathogenesis. Vacuolar changes with foamy macrophages are found predominantly in the myelin of the dorsal and lateral columns of the thoracic spinal cord, resembling changes seen in subacute combined degeneration. Occasionally diffuse cord changes are seen. Signs of active HIV infection such as microglial nodules and infected macrophages are not thought to be associated. Pathologic evidence of productive HIV infection within the spinal cord is only found in about 6% of patients. The specific cause is unknown; however, a deficiency of transmethylation pathways and cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor, may be important.

3. Clinical features. Progressive painless spastic paraparesis, with sensory ataxia and neurogenic bladder, is consistent with vacuolar myelopathy.

4. Diagnosis. HIV myelopathy is a diagnosis of exclusion and should be made based on clinical features in the setting of HIV. CSF should be obtained to exclude other conditions and etiologies, such as B12 deficiency, syphilitic myelitis, tuberculous myelitis, human T-cell lymphotropic virus type I (HTLV-1), cytomegalovirus (CMV) myeloradiculitis, and varicella zoster virus (VZV) myelitis. MRI of the spinal cord can be normal, reveal atrophy, or rarely have increased T2 signal.

5. Management. No specific therapy has been shown to prevent progression of myelopathy. Optimizing ART is recommended although it has not been demonstrated to have a favorable effect on neurologic deficits. Spasticity can be managed with baclofen or tizanidine and painful dysesthesias may be treated with lamotrigine or desipramine. Urinary frequency, urgency, and incontinence may be relieved with anticholinergic agents such as oxybutynin.

External supports enhance safer mobility in patients with sufficient leg strength. Motorized scooters or wheelchairs can maintain mobility in weaker patients who are otherwise capable of independent activity.

6. Outcomes. Most individuals have a slow progressive course over time. Since patients have prolonged survival due to effective ART, the focus is now on managing chronic disability with routine neurologic evaluation to adjust supportive therapy. Abrupt neurologic changes should prompt evaluation for superimposed OIs.

C. HIV distal sensory polyneuropathy (HIV-DSP).

1. Epidemiology. HIV-DSP is the most common neurologic complication in HIV with an estimated incidence of 33% to 50%. Prior to the widespread use of effective ART, risk factors were thought to be low CD4 count, elevated HIV viral load, and use of neurotoxic ART (didanosine, stavudine, and zalcitabine). More recent studies have demonstrated that there appears to be an increased risk in patients with a history of substance abuse, older age, diabetes, hypertriglyceridemia, and that longer survival in HIV-infected patients may result in continued significant morbidity from this condition.

2. Pathogenesis. HIV-DSP is due to distal degeneration of long axons, macrophage infiltration, and a loss of neurons in the dorsal root ganglion (DRG). The process predominately affects distal small unmyelinated fibers with involvement of myelinated fibers in more severe cases. Neurotoxicity can occur by direct infection of the peripheral nerve by the virus or various indirect immunomodulatory mechanisms. HIV-DSP can also be associated with ART, most commonly the di-deoxynucleosides, which are thought to cause neurotoxicity by causing mitochondrial dysfunction.

3. Clinical features. The most prominent symptom of HIV-DSP is a symmetric, burning, stabbing, or shooting pain that can be disabling in severity. Initial symptoms include paresthesias and numbness starting at the feet which may gradually ascend. Balance can be affected if involvement of larger fibers occurs. Physical examination demonstrates impaired vibratory sensation, pin-prick and temperature perception, and absent/diminished ankle reflexes. Sensory ataxia and weakness of small muscles in the feet is also common.

4. Diagnosis. HIV-DSP is a diagnosis of exclusion of other small fiber neuropathies, particularly toxic neuropathy associated with di-deoxynucleosides which appears clinically similar. Other causes of neuropathy need to be excluded, such as vitamin B12 deficiency, diabetes, uremia, alcoholism, hypothyroidism, and hepatitis C which may mimic or influence the neuropathic features.

Confirmatory diagnostic tests may include electromyography (EMG), nerve conduction studies (NCS), and skin biopsy. EMG may show active or chronic denervation patterns, NCS may show decreased amplitude or absence of sural nerve sensory potentials, and skin biopsy may show a decrease in epidermal nerve fiber density.

5. Management.

a. There is no established therapy for HIV-DSP, and treatment should be directed at symptomatic relief.

b. No agents are currently FDA approved for the treatment of HIV-DSP. Pain relief is important to optimize function and improve quality of life. Medications for treating other neuropathic pain syndromes are typically used including AEDs, antidepressants, and nonspecific analgesics including opioids.

c. ART has not been convincingly shown to modify the course of the neuropathy; however, higher plasma viral load has been associated with pain severity in some studies.

d. Neurotoxic agents should be discontinued whenever possible, particularly di-deoxynucleosides. Toxic neuropathy may persist for 6 to 8 weeks after discontinuation of these agents, and occasionally may temporarily worsen.

e. Any metabolic deficiencies should be corrected.

f. Topical lidocaine or capsaicin formulations may be effective adjuvants.

g. Nonpharmacologic approaches such as acupuncture, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, biofeedback, and relaxation therapies can be tried.

6. Outcomes. Symptomatic management can be helpful in alleviating discomfort; however, reversal of HIV-DSP is unlikely. Acute worsening of symptoms may arise when concurrent pathologies are present; and if this occurs, should be further investigated.

D. Inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (IDP).

1. Epidemiology. Individuals with HIV rarely develop acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (AIDP) or chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP), with the incidence of these neuropathies unknown. AIDP is similar to Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS) in non–HIV-infected persons. It usually occurs early in the course of HIV infection and may represent a response to seroconversion. CIDP results from immune-mediated demyelination and may be relapsing or progressive.

2. Pathogenesis. IDP at the time of HIV seroconversion is thought to result from an immune reaction to HIV and targets peripheral myelin.

3. Clinical features. Individuals with IDP present with progressive, symmetric motor weakness, variable sensory and autonomic features, and areflexia. Symptoms usually begin in the distal lower extremities and ascend over days with some individuals progressing to respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilatory support. Patients with clinical progression after the first 4 to 6 weeks by definition have CIDP. CIDP may follow a progressive or relapsing course over months with motor weakness and areflexia but with more prominent sensory impairment.

4. Diagnosis. There are typical features suggestive of IDP which help assist with the diagnosis. Electrophysiologic studies reveal prominent slowing and motor nerve conduction blocks, prolonged or absent F-wave responses, and variable degree of axonal damage and denervation. CSF may demonstrate a moderate mononuclear pleocytosis up to 50 cells/mL along with a prominent protein elevation.

5. Management.

a. Plasma exchange (PLEX) with a course of 200 to 250 mL/kg divided into five or six exchanges over a 2-week period has been shown to be effective. Intravenous immune globulin (IVIG) (400 mg/kg/day for 5 days) is an alternative therapy shown to be beneficial. Individuals with CIDP need maintenance therapy with one treatment every 2 to 4 weeks.

b. Individuals with impending respiratory failure need elective intubation with ventilator support until adequate respiratory function returns.

c. Adjunctive therapy is important to prevent complications of immobility and maintain function in anticipation of neuromuscular recovery. Physical therapy should be initiated at the bedside with passive range of motion to prevent contractures and advance as strength is improved. Neuralgic pain can be treated as in patients with HIV-DSP. As strength improves, mobilization may require support devices and orthotics.

6. Outcomes. AIDP usually resolves and most individuals have recovery. CIDP has a more variable outcome with residual impairment often persisting.

E. HIV myopathy.

1. Epidemiology. Symptomatic and primary muscle disease is uncommon in HIV-infected individuals, however rarely a polymyositis-like syndrome can occur. In the latter half of the 1980s, after the widespread use of zidovudine (AZT) was initiated, a secondary myopathy attributable to muscle toxicity began to emerge. Zidovudine myopathy usually appears after at least 6 months of treatment and is thought to be a result of mitochondrial toxicity. A study of 86 patients on AZT for more than 6 months revealed 16% had persistently elevated creatine kinase (CK) and 6% had symptomatic myopathy. Uncommonly, OIs may cause myositis (i.e., toxoplasmosis) and should also be investigated if medication cessation does not lead to resolution of symptoms.

2. Pathogenesis. AZT likely causes mitochondrial toxicity in muscle through inhibition of the mitochondrial enzyme DNA polymerase gamma. The cause of myopathies unassociated with AZT is unknown, but pathologic findings include rod body myopathy, necrotizing and nonnecrotizing inflammatory myopathy, and type 2 muscle fiber atrophy found in HIV-1–associated muscle wasting syndrome. Immunologic factors are also thought to play an important role.

3. Clinical features. Individuals typically present with symmetric proximal muscle weakness of the hip or shoulder girdle muscles. Difficulty squatting, rising from a chair, or walking up stairs are typical presenting symptoms of myopathy. Some individuals also have myalgias and muscle tenderness.

4. Diagnosis. In addition to having clinical features suggestive of myopathy, serum CK is typically elevated. EMG of weak muscles demonstrates small myopathic motor unit potentials with increased recruitment, fibrillation, and complex discharges. Muscle biopsy may reveal scattered muscle fiber degeneration and inflammatory infiltrates of CD8+ T lymphocytes and macrophages. Mitochondrial abnormalities and inclusions such as nemaline rod bodies may be present.

5. Management. In patients taking AZT, discontinuation of the medication may result in improvement of the myopathy. In patients who continue to deteriorate after AZT is stopped, biopsy to evaluate for opportunistic or inflammatory myositis should be considered. Prednisone has been used with variable success in patients with polymyositis or rod body myopathy, although the natural history of these myopathies is uncertain and the relation of improvement to treatment is unclear.

6. Outcomes. Most patients respond to discontinuation of toxic medications (i.e., AZT) or treatment with corticosteroids. Lack of response to empiric therapy should prompt a muscle biopsy.

F. Aseptic meningitis.

1. Epidemiology. HIV is often overlooked as a cause of aseptic meningitis, meningoencephalitis, or encephalitis. It can cause neurologic features in up to 17% of patients and acute aseptic meningitis in 1% to 2% of all primary HIV infections. Neurologic symptoms may occur or develop up to 3 months after the onset of symptoms of acute HIV when the other symptoms have resolved.

2. Clinical features. Patients may present with headache, fever, and neck stiffness. They may occasionally have a positive Kernig’s or Bruzdinski’s sign, cranial neuropathy, confusion, or lethargy.

3. Diagnosis. Patients with HIV may have a chronic, subclinical aseptic meningitis. CSF analysis may show a modest lymphocytic pleocytosis, mild elevation of protein, and elevated gamma globulin index.

4. Management. The importance of this condition is in its potential for causing diagnostic confusion particularly in the evaluation of neurosyphilis or other CNS OIs. Practitioners should also be cognizant of the fact that aseptic meningitis or meningoencephalitis can be a presenting symptom of acute HIV and individuals with this clinical presentation should be tested for HIV and if deemed appropriate, started on effective ART without delay.

5. Outcomes. Aseptic meningitis is often self-limited but can recur at any time following the initial infection. It is possible that it may be associated with a more rapid progression of HIV-related disease.

Advances in ART have decreased the incidence of CNS OIs; however, they continue to occur as presenting manifestations of AIDS, particularly in patients who have poor responses to ART or have limited access to medications. Most OIs that affect the CNS are AIDS-defining conditions. They include cryptococcal meningitis, toxoplasmosis, primary CNS lymphoma (PCNSL), progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), CNS infection by CMV, CNS varicella zoster virus (VZV), CNS tuberculosis (TB), and have a high associated mortality. The above conditions including neurosyphilis will be reviewed as they are the most common CNS infections affecting PLWHA worldwide. Only the most common OIs are reviewed here.

A. Cryptococcal meningitis.

1. Epidemiology. Cryptococcal meningitis is a fungal infection most commonly caused by Cryptococcus neoformans (![]() Video 48.1). It is a ubiquitous environmental encapsulated yeast found in the soil and pigeon droppings, acquired through inhalation and spreads to the CNS hematogenously. It is more common than any other systemic fungal infection in PLWHA and is the most common opportunistic pathogen causing meningitis in PLWHA. In addition to meningitis, it can cause localized cryptococcomas in brain parenchyma and extra-neurologic cryptococcal infection in the lung, bone marrow, liver, urinary tract (prostate), and skin. It usually occurs in patients with HIV/AIDS who have a CD4 count ≤100 cells/mm3. The incidence of cryptococcal meningitis has declined as patients have had increased access to effective ART; however, this infection continues to remain one of the leading causes of mortality in regions where access to effective ART is limited and diagnosis of HIV is delayed.

Video 48.1). It is a ubiquitous environmental encapsulated yeast found in the soil and pigeon droppings, acquired through inhalation and spreads to the CNS hematogenously. It is more common than any other systemic fungal infection in PLWHA and is the most common opportunistic pathogen causing meningitis in PLWHA. In addition to meningitis, it can cause localized cryptococcomas in brain parenchyma and extra-neurologic cryptococcal infection in the lung, bone marrow, liver, urinary tract (prostate), and skin. It usually occurs in patients with HIV/AIDS who have a CD4 count ≤100 cells/mm3. The incidence of cryptococcal meningitis has declined as patients have had increased access to effective ART; however, this infection continues to remain one of the leading causes of mortality in regions where access to effective ART is limited and diagnosis of HIV is delayed.

2. Pathogenesis. Cryptococcal spores enter the body via inhalation, which leads to primary pulmonary infection, latent infection, or disseminated systemic infection with a tendency to localize to the CNS. In patients with HIV, most cases of cryptococcal meningitis represent reactivation of latent infection.

3. Clinical features. The most common presentation of C. neoformans is meningitis with symptoms of headache, malaise, and fever. It can cause increased intracranial pressure (ICP); thus some patients may present with altered mental status, papilledema, personality changes, hearing loss, lethargy, or memory loss. Peripheral facial nerve involvement associated with AIDS is the most common cranial neuropathy. Seizures and focal CNS signs may be observed with parenchymal involvement and cerebral infarctions been reported.

4. Diagnosis. In patients with meningitis, radiographic imaging may be normal or show meningeal enhancement. Brain MRI is recommended in HIV patients to evaluate for space-occupying lesions, in patients with focal neurologic deficits, or clinical manifestations of increased ICP prior to obtaining a lumbar puncture (LP). An LP for CSF examination is essential in making the diagnosis of cryptococcal meningitis. CSF opening pressure should be measured at the time of LP. CSF usually demonstrates a lymphocytic pleocytosis, elevated protein, and low glucose. It is important to note, the CSF profile can be normal in 30% of patients. India Ink stain of the CSF can be done quickly, but requires an experienced technician and if positive can show round encapsulated yeast. It has a low sensitivity in early infection and is not diagnostic in 10% to 30% of HIV-infected patients. Detection of the CSF cryptococcal antigen (CrAg) supports the diagnosis of cryptococcal meningitis with sensitivity of 93% to 100% and specificity of 93% to 98%. CSF culture is usually positive in a patient with meningitis within 3 to 7 days; however, results may be negative when cryptococcomas are present, thus requiring biopsy of the lesion. Serum CrAg is highly sensitive and positive in 91% to 92% of cases, and should be performed in patients with suspected cryptococcal meningitis.

5. Management. Treatment of cryptococcal meningitis is comprised of three phases: induction, consolidation, and maintenance.

a. Induction therapy. Mortality in cryptococcal meningitis often occurs in the first 2 weeks of therapy. Induction therapy with Amphotericin B plus Flucytosine for 2 weeks is recommended in patients with cryptococcal meningitis or extrapulmonary cryptococcosis. Flucytosine is recommended since it leads to rapid sterilization of the CSF and is associated with increased rates of survival. For patients unable to tolerate Amphotericin B or those in resource-limited countries where access to the medication may be limited, high-dose fluconazole has been used. Induction is usually continued for at least 14 days, but in seriously ill patients, therapy may be extended.

b. Consolidation therapy. After at least 14 days of successful induction therapy. Defined as substantial clinical improvement and negative CSF culture after repeat LP. Patients are treated with fluconazole 400 mg daily for 8 weeks.

c. Maintenance therapy. Fluconazole 200 mg daily is continued for at least 1 year. Maintenance therapy can be terminated when the following criteria are met: completion of initial (induction and consolidation) therapy and at least 1 year of maintenance therapy; patient remains asymptomatic from cryptococcal infection; and CD4 count remains at 100 cells/mm3 for 3 or more months with suppressed HIV RNA on effective ART. If CD4 falls below 100 cells/mm3 maintenance therapy should be re-initiated and patients should be reevaluated for cryptococcal meningitis if deemed appropriate.

d. Adjunctive therapy. Elevated ICP is a common and serious complication in cryptococcal meningitis and occurs in over 50% of patients. It is vital to aggressively manage increased ICP with serial LPs, and, if necessary, lumbar drains or ventriculo-peritoneal shunts (VPS). The goal of treatment is to have ICP within normal range. Acetazolamide or mannitol therapy is not recommended as it has been associated with adverse events. ART should be initiated; however, the timing of this is still uncertain as it may be associated with immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) in up to 30% of cases (Section J under Opportunistic Infections) and may be associated with increased morbidity and mortality.

e. Timing of ART. ART should be initiated, however the timing of this in acute disease is controversial as studies have shown conflicting data. Currently, the Panel on Opportunistic Infections in HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents recommends delaying ART until induction therapy or induction/consolidation therapy has been completed in those with severe disease. It is noted that in patients with severe immune deficiency (CD4 <50 cells/mm3), earlier initiation of ART may be needed. If ART is initiated in these individuals, they should be monitored for signs and symptoms of IRIS.

6. Outcomes. Acute mortality from cryptococcal meningitis in patients with HIV/AIDS ranges from 11% to 45%, with the majority of deaths occurring during the first 2 weeks. Important prognostic factors are the degree of obtundation at presentation and the presence and response to treatment of increased ICP. Other factors reported to negatively affect prognosis are CSF CrAg >1:1,024, extra-neurologic cryptococcal infection, low CSF and WBC count, and hyponatremia. CSF should be sampled after completion of induction therapy and those with persistently positive cryptococcal cultures should be managed with continued higher doses of anti-fungals. Serum CrAg cannot be used to manage disease response.

B. CNS toxoplasmosis.

1. Epidemiology. Toxoplasma gondii is an intracellular protozoan most commonly acquired by consumption of undercooked or contaminated meat or ingestion of oocysts in an environment contaminated with cat feces. The prevalence in the U.S. is about 11%. The parasite typically remains dormant in the absence of immune suppression and disease develops through reactivation of latent cysts, with greatest risk in those with CD4 <100 cells/mm3. Seropositive individuals not on effective prophylaxis have a 30% risk of reactivation. The widespread use of ART and the practice of using trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for the prevention of Pneumocystis Jirovecii (PJP) Pneumonia has helped decrease the incidence of CNS toxoplasmosis.

2. Pathogenesis. Toxoplasma protozoa invade the intestinal epithelium and spread throughout the body leading either to primary infection, or more commonly, establishment of latent infection in various tissues. In immune compromised hosts, clinical disease results from reactivation of latent disease with the most common site being the CNS. Toxoplasmosis is considered the most common cause of HIV-associated focal CNS disease.

3. Clinical features. The most common presentation is a focal encephalitis with headache (55%), confusion (52%) and fever (47%). Common manifestations are seizures, impaired mentation and focal abnormalities such as hemiparesis, hemiplegia, hemisensory loss, cerebellar ataxia, visual field defects, cranial nerve palsies, and aphasia. Involvement of the basal ganglia can result in movement disorders.

4. Diagnosis. Definitive diagnosis of CNS toxoplasmosis requires a compatible clinical syndrome, identification of one or more mass lesions by brain imaging, and detection of the organism in a specimen.

Presumptive diagnosis of CNS toxoplasmosis is made if the patient has a CD4 count less than 100 cells/mm3, compatible clinical syndrome and not been on effective prophylaxis, positive serum toxoplasma serology, and characteristic brain imaging. Based on this criteria, there is a 90% probability the diagnosis is CNS toxoplasmosis. Patients should be started on therapy with repeat brain imaging performed in 2 weeks to evaluate for response.

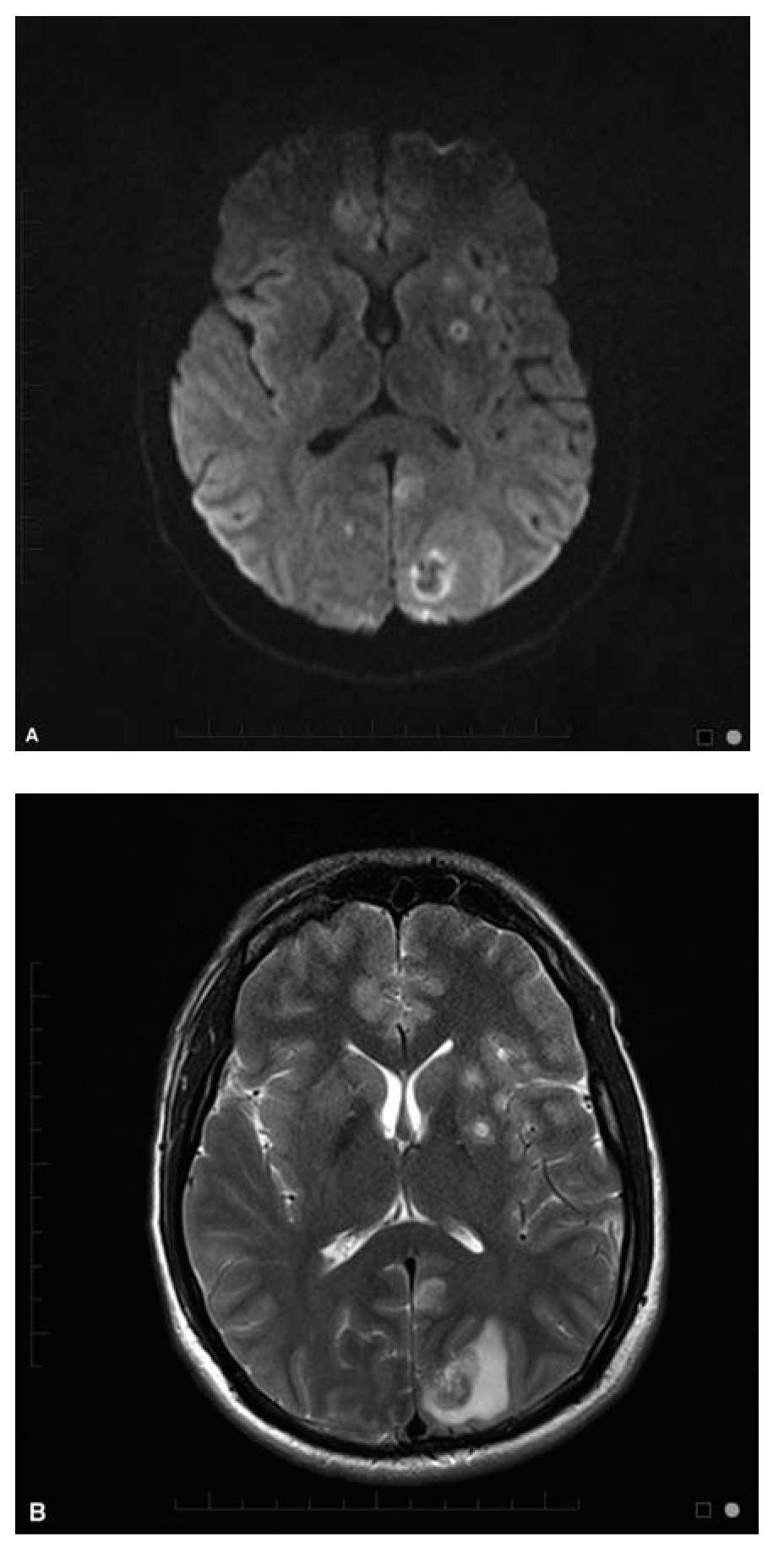

Brain MRI usually shows multiple ring enhancing lesions which often involve the basal ganglia and gray-white junction in 90% of patients (Fig. 48.1A and B). The appearance of the mass lesions is nonspecific, although a signet ring sign has been suggested to be highly suggestive when present. An isolated mass lesion can occur in up to 14% of patients, and non-enhancing infarction-like patterns, meningoencephalitis, and myelitis have been reported. Radionuclide imaging with thallium single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) can be helpful in differentiating abscesses from primary CNS lymphoma (PCNSL), but does not distinguish toxoplasmosis from other abscesses.

Toxoplasma IgG antibodies are present in the blood in almost all cases, although rare cases of seronegative pathologically proven toxoplasmosis have been described. Specific antibodies to T. gondii and Toxoplasma DNA can be detected in the CSF which can assist with the diagnosis, having a sensitivity of 68.8% and specificity of 100%. Definitive diagnosis requires pathologic demonstration of organisms or their DNA. Diagnostic brain biopsy is indicated in patients with negative serology for T. gondii and single lesions, worsening lesions, or those failing to respond after 2 weeks to antibiotic therapy directed at the organism.

5. Management.

a. Prophylaxis. Patients who have a positive serum toxoplasma IgG with a CD4 count <100 cells/mm3 should be placed on primary prophylaxis. The preferred drug of choice is trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole since most patients are placed on it for PJP prophylaxis which is initiated when CD4 count <200 cells/mm3. Alternative regimens for primary prophylaxis are available and should be initiated with the assistance of a specialist. Prophylaxis can be discontinued once a patient’s CD4 count exceeds 200 cells/mm3 for 3 or more months in response to effective ART.

b. Treatment. Management of CNS toxoplasmosis includes an induction phase for acute symptoms followed by a maintenance phase to prevent recurrence of infection. Patients with cerebral toxoplasmosis typically have a rapid response to therapy thus empiric treatment in patients with cerebral lesions suggestive of the infection and positive serology is warranted. A clinical response is expected within 2 weeks. The treatment of choice is oral sulfadiazine + pyrimethamine + leucovorin; however, pyrimethamine + clindamycin + leucovorin is the preferred alternative regimen in those unable to tolerate sulfadiazine. Patients who are severely ill and unable to take oral medications can be treated with IV trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Corticosteroids can be used in those with increased ICP; however, if possible should be avoided in those empirically treated for CNS toxoplasmosis as their use can lead to diagnostic confusion with CNS lymphoma.

Induction therapy is continued for at least 6 weeks or until there is regression of all lesions. Once this has occurred, patients are placed on maintenance therapy with a lower dose of the same regimen to reduce risk of recurrent infection until their CD4 count remains >200 cells/mm3 for at least 6 months in response to effective ART.

6. Outcomes. Therapeutic monitoring is particularly important for patients treated empirically for CNS toxoplasmosis. Imaging should be repeated approximately 2 weeks after the initiation of antibiotic therapy. Failure of lesions to respond to therapy or worsening lesions should prompt a brain biopsy to evaluate for an alternate or concurrent process.

FIGURE 48.1 (A) Axial Diffusion weighted image (DWI) and (B) T2 weighted images in a 28-year-old man HIV+ with CNS toxoplasmosis. CNS, central nervous system; HIV, human immune deficiency virus. (Courtesy of Dr. Jordan Rosenblum)

C. Primary CNS lymphoma.

1. Epidemiology. Primary CNS lymphoma (PCNSL) became an AIDS-defining malignancy in 1983 and accounts for 15% of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) in HIV-infected populations. It is a subtype of diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) containing Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) and is 1,000 times more common in HIV-infected patients. PCNSL typically presents in patients with advanced HIV disease having a CD4 count ≤50 cells/mm3 and most have had a prior OI. The widespread use of ART in PLWHA has significantly decreased the incidence of PCNSL after 1996 from 313.2 per 100,000 person-years to 77.4 per 100,000 person-years.

2. Pathogenesis. PCNSL is strongly associated with the Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), a member of the herpes virus family and correlated to HIV immunodeficiency. Studies have demonstrated that EBV is incorporated into the genome of neoplastic cells and as HIV infection progresses infected B cells reach the CNS. EBV infection can lead to PCNSL in patients with advanced AIDS by transforming B cells due to its oncogenic properties, enhanced stimulation and reduced immunosurveillance against B cells, depletion of EBV-specific CD8+ T cells by HIV, and EBV induced mutations of tumor-suppressor genes and proto-oncogene activation.

3. Clinical features. Patients with PCNSL tend to have nonspecific clinical features and diagnosis may be delayed by empiric treatment for CNS toxoplasmosis. Common symptoms on presentation are subacute progressive headache, lethargy, cognitive impairment, seizures, and focal neurologic deficits related to tumor location, such as hemiparesis, aphasia, ataxia, or visual field deficits. Signs and symptoms of increased ICP such as headache, nausea, vomiting, and papilledema may be present. Meningitis, meningoencephalitis, or meningoradiculitis with cranial nerve abnormalities are commonly seen in patients with leptomeningeal lymphoma. Typical B systemic symptoms are not usually present.

4. Diagnosis. As with other CNS malignancies, diagnosis of PCNSL is made radiographically in conjunction with CSF analysis. CT or MRI can be used to characterize CNS lesions, although the latter is preferred since it is more sensitive, accurate, and can detect smaller lesions. Brain MRI tends to show solitary or multiple contrast enhancing, irregularly shaped lesions most commonly located in the periependymal area, corpus callosum, or periventricular area. Lesions may be difficult to differentiate from CNS toxoplasmosis or other cerebral abscesses by MRI. Thallium single-photon emission CT (SPECT) can show increased uptake in PCNSL and can be used to differentiate from toxoplasmosis with a sensitivity and specificity of about 90%.

Routine CSF analysis yields a diagnosis of PCNSL in about 25% of patients. CSF examination tends to reveal normal glucose and protein with normal or increased lymphocytes. The detection of EBV DNA in the CSF by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) suggests lymphoma and is nearly 100% sensitive and about 50% specific.

Brain biopsy is the gold standard to assist with diagnosis of focal brain lesions. Usually patients with brain lesions are empirically treated for toxoplasmosis despite their serologic status and may also receive corticosteroids which can confuse the biopsy results. This can delay diagnosis and expose patients to potentially dangerous medication side effects particularly in those with negative serology for toxoplasmosis. Thus, unless there is an absolute contraindication in a patient with AIDS sterotactic brain biopsy should be performed to make a diagnosis if lesions fail to respond to empiric therapy or if they are worsening.

5. Management. The cornerstone of therapy in patients with PCNSL is ART with the goal of effective immune reconstitution. In the pre-HAART era, outcomes were poor as patients with PCNSL had an overall median survival of 2.6 months. There is debate about the use of anticonvulsants and steroids since there is the potential for the latter to confound histologic diagnosis. A few days of steroid treatment may be useful particularly when there is mass effect, however prolonged course would not be recommended.

Radiation therapy has been the mainstay of management along with ART, however it can be associated with delayed CNS toxicity. More recently, high-dose methotrexate in combination with rituximab administered for eight cycles with or without radiotherapy has been shown to be effective. A recent report also described five HIV-infected patients with PCNSL who underwent autologous stem cell transplant after induction chemotherapy, with two of them in remission 2 years post-transplant and two doing well 7 months post-transplant.

6. Outcomes. HIV seropositive status is typically an exclusion criteria for prospective PCNSL studies, thus therapeutic regimens have been adopted from data in immune competent patients. Large population-based studies have shown with the widespread use of ART, there are reasonable 1-year survival rates of about 54% and 5-year survival rates of about 23%.

D. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy.

1. Epidemiology. PML is a demyelinating disease of the CNS caused by reactivation of the John Cunningham virus (JCV). It is a polyoma virus which causes asymptomatic primary infection in childhood and remains latent in the kidneys, bone marrow, and lymphoid tissue. Prior to the ART era, the prevalence of PML was 0.3% to 8% with less than one-tenth surviving more than 1 year.

2. Pathogenesis. Primary JCV infection is typically asymptomatic and the virus remains latent in the kidneys, bone marrow, and lymphoid tissue. The events leading to PML remain uncertain. About 50% to 90% of individuals are seropositive for JCV and once cellular immunosuppression occurs, it can reactivate and spread to the brain, primarily infecting oligodendrocytes, astrocytes, and occasionally cerebellar granular cells eventually leading to demyelination in white matter. HIV may be a cofactor for JCV replication by the HIV TAT protein which may provide another mechanism of pathogenesis.

3. Clinical features. PML usually occurs in patients with CD4 <100 cells/mm3 however it has been described in those with higher CD4 counts. JCV leads to demyelination of the white matter leading to cognitive impairment and focal neurologic deficits. Common signs and symptoms include subacute cognitive impairment, visual field defects, hemiparesis, ataxia, and speech or language disturbances evolving over weeks. Some patients come to medical attention with seizures or acute stroke-like presentations while others may evolve over several months with eventual progression to dementia followed by coma and death.

In the pre-ART era, median survival was about 6 months, although those with less immune suppression survived longer. Effective ART therapy has extended survival to years although patients often have residual neurologic impairments. Higher JC virus load in the CSF may be associated with poorer prognosis while the presence of specific JC virus CD8+ immune cells has been associated with better prognosis.

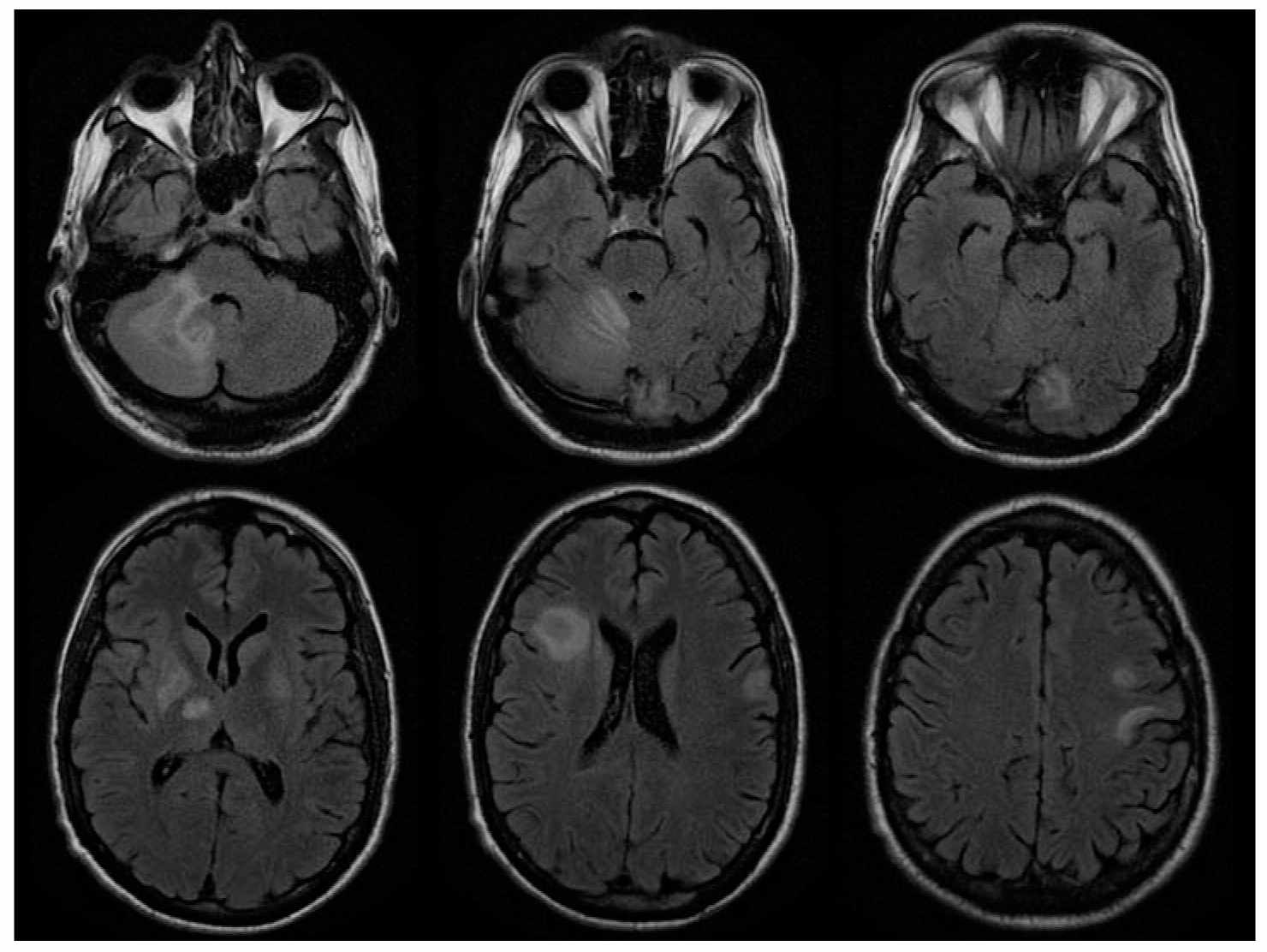

4. Diagnosis. PML can be diagnosed based on clinical presentation in conjunction with neuroimaging and detection of JCV DNA in the CSF or brain biopsy. MRI typically demonstrates asymmetric lesions in cerebral white matter on T2-weighted sequences. A scalloped appearance reflecting involvement of the subcortical arcuate fibers is suggestive when present (Fig. 48.2). Frontal, parietal, temporal, basal ganglia, cerebellar and brainstem lesions may be seen. In contrast to other settings in which the disease occurs, PML lesions in AIDS enhance following contrast infusion in a minority of cases, usually in relatively less immunosuppressed patients. Single lesions are sometimes seen. Definitive diagnosis requires confirmation of JCV infection, by brain biopsy, or by demonstration of JCV DNA in CSF in a patient with compatible clinical and imaging features. High-sensitivity JCV PCR assays which can detect 50 copies/mL or less should be used to analyze CSF.

5. Management. Currently only effective ART to help restore immune function has been shown to benefit AIDS-associated PML. Reports show that survival rates have increased from 10% in the pre-ART era to 50% to 75% since. CNS IRIS is a potential complication following initiation of ART and may be difficult to distinguish from worsening PML (see discussion of IRIS in Section J under Opportunistic Infections). Controlled trials with cytosine arabinoside and cidofovir failed to show any benefit. Case reports suggest possible benefit with mirtazapine.

6. Outcomes. The prognosis of PML is poor with a median survival of about 6 months in HIV-infected patients. Prolonged survival is associated with the use of ART, elevated CD4 count at the time of diagnosis, increased CD4 count by 100 cells/mm3, low HIV RNA, PML as an initial AIDS diagnosis, low JCV levels in CSF, clearance of JCV in CSF, and lack of neurologic progression after diagnosis.

E. Cytomegalovirus.

1. Epidemiology. CMV is a double-stranded DNA virus that belongs to the herpes virus family. CMV is ubiquitously acquired, and serologic evidence of exposure is present in most adults. Although some may have a transient systemic illness on acquisition, normal immune function prevents further manifestations. Clinical evidence of disease in HIV-infected patients is typically seen in individuals with a CD4 count ≤50 cells/mm3 with retinitis being the most common end-organ presentation of disease, occurring in 30% of PLWHA in the pre-ART era. Prior to the advent of ART, neurologic complications of CMV occurred in about 2% of patients with AIDS and could be fatal.

2. Pathogenesis and clinical features. In PLWHA, CMV disease is due to reactivation of latent infection with end-organ disease resulting from hematogenous spread of the virus. Risk factors for CMV infection include CD4 count ≤50 cells/mm3, HIV RNA >100,000 copies/mL, high level of CMV viremia, and history of prior OI.

FIGURE 48.2 A 38-year-old man with cortico-subcortical type of suprabulbar palsy. MRI demonstrated patchy areas of abnormal increased T2 and FLAIR signal abnormality involving bilateral frontal lobe subcortical white matter, bilateral basal ganglion and thalami with some extension into the right cerebral peduncle, as well as right cerebellum. FLAIR, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging. (Courtesy of Dr. José Biller)

Neurologic manifestations of CMV infection include encephalitis, polyradiculomyelitis, multifocal neuropathy, meningomyelitis, and myositis. CSF analysis typically demonstrates a lymphocytic pleocytosis, low to normal glucose, and normal to elevated protein content.

a. CMV encephalitis (CMVE) usually presents in advanced HIV/AIDS infection and is characterized by subacute confusion, delirium, impaired attention, memory, and cognitive processing with varying focal signs, including cranial neuropathy, nystagmus, weakness, spasticity, and ataxia. Focal encephalitis with mass lesions or aseptic meningitis can also occur.

b. CMV polyradiculomyelitis (CMVRM) presents as a subacute motor weakness with areflexia and sphincter dysfunction (usually urinary and/or bowel) that evolves over days to weeks. Painful paresthesias in the perineum and lower-extremities along with features of myelopathy such as a sensory level and Babinski’s signs, may be found on examination. Symptoms in the lower extremities may ascend resembling GBS.

c. CMV multifocal neuropathy is characterized by motor weakness, depressed reflexes, and sensory deficits. It involves nerves of both upper and lower extremities in an asymmetric pattern evolving over weeks to months. Motor features overshadow the sensory findings.

d. CMV can less commonly cause myositis or meningomyelitis.

3. Diagnosis. The clinical syndromes are suggestive but not pathognomonic for CMV infection in severely immunosuppressed patients with AIDS. MRI with contrast may reveal enhancement of ventricular ependyma in CMVE, of meninges in some patients with meningoencephalitis or meningomyelitis, and of lumbar nerve roots or conus medullaris in some patients with CMVRM. Normal findings or nonspecific atrophic changes may also be seen.

CSF analysis in CMVRM characteristically reveals a polymorphonuclear pleocytosis, elevated protein, and low glucose. In CMVE, CSF pleocytosis is less common, and in CMV multifocal neuropathy CSF is usually normal or reveals a nonspecific protein elevation. Detection of CMV DNA in CSF using PCR amplification techniques is a sensitive and specific indicator of active CMV infection, exceeding 80% and 90%, respectively, thus avoiding the need for a brain biopsy. Patients with AIDS and CMV infection of the nervous system typically have systemic viremia as well; however, the level of viremia does not correlate with end-organ disease and has poor diagnostic and predictive value.

4. Management. No randomized controlled studies of treatment of CMV CNS OIs have been conducted. There are three available agents for the management of CMV infection. Given the poor prognosis with monotherapy, combination therapy with ganciclovir and foscarnet is now recommended by the panel on Opportunistic Infections in HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents.

a. Ganciclovir (GCV) is administered as an induction dose of 5 mg/kg IV twice daily in those with normal renal function for 21 days followed by a maintenance dose of 5 mg/kg daily. Potential adverse effects include thrombocytopenia, anemia, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain.

b. Foscarnet (FOS) is thought to have greater CNS penetration than Ganciclovir; however, it has more adverse effects. An induction dose of 90 mg/kg IV twice daily in those with normal renal function for 21 days is followed by a maintenance dose of 90 mg/kg daily. Potential adverse effects include renal dysfunction, proteinuria, nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (hypokalemia, hypocalcemia, hypomagnesemia), headache, nausea, fatigue, and leukopenia.

c. Cidofovir (CDV) is administered at 5 mg/kg in 1L of IV fluids once a week for two successive weeks and then every 2 weeks in those with normal renal function. Probenecid 2 g orally is given 2 hours prior to the infusion and 1 g orally is given 2 and 8 hours upon completion of the infusion. Patients should have ocular monitoring for hypotony and renal function for acute kidney injury. Other adverse events include dose-dependent proximal tubular injury (Fanconi-like syndrome, with proteinuria, glycosuria, bicarbonaturia, phosphaturia, polyuria), nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, acidosis, nausea, fever, and alopecia.

d. Viral resistance may develop during prolonged therapy. CMV neurologic disease emerging while on maintenance therapy for another etiology of CMV disease (i.e., retinitis or enteritis) should be managed with an alternative agent while viral resistance testing is sent. The most common resistance mutations occur in the viral UL97 kinase or the UL54 DNA polymerase gene. GCV resistance mutations have been identified in both genes, while FOS and CDV mutations occur in only the DNA polymerase gene.

5. Outcomes. There are no RCTs to help guide therapy for AIDS-related CMV neurologic disease as responses to therapy are reported anecdotally. The optimal regimen remains unknown with each therapeutic option having pros and cons. Immunosuppressed patients should receive induction therapy and then transition to maintenance therapy. CSF evaluation may be the best marker of CNS disease activity and should be performed at the completion of induction therapy and if worsening neurologic functioning occurs.

F. Varicella Zoster virus.

1. Epidemiology. VZV commonly occurs in patients with HIV infection at multiple stages of the disease and may produce encephalitis, myelitis, and mono or polyradiculitis. Patients with radiculitis often have self-limited dermatologic eruptions, which may be accompanied by prolonged neuralgia. CNS extension may be marked by vasculitis resulting in cerebral infarction, particularly after ophthalmic zoster, and can result in necrotizing myelitis and brainstem, focal or diffuse cerebral encephalitis.

2. Pathogenesis. VZV, the virus which causes chicken pox, is acquired early in life and resides latently in sensory ganglia where it can intermittently produce recurrent radiculitis. Retrograde extension to the CNS along contiguous sensory roots and fiber tracts has also been demonstrated. This can lead to vasculitis, meningitis, or encephalitis.

3. Clinical features.

a. VZV radiculitis is characterized by painful paresthesias in a restricted dermatomal distribution of a spinal or trigeminal nerve root. A vesicular rash usually follows, but VZV can occur without a rash. The skin eruption typically heals over weeks; however, pain may persist.

b. VZV myelitis may be limited or progressive resulting in spastic weakness, sensory impairment, and sphincter dysfunction. It is sometimes associated with myoclonus or meningitis. Dermatomal VZV may or may not be present.

c. VZV meningitis presents with headache, fever, altered mental status. CSF examination demonstrates a lymphocytic pleocytosis, increased protein, and normal to decreased glucose.

d. Polyradiculitis is clinically indistinguishable from CMVRM. It can also be caused by VZV.

e. VZV encephalitis can be focal or diffuse in PLWHA. It can manifest as seizures, confusion, progressive language and cognitive impairment, and sensory or motor abnormalities. Progression can be gradual and meningitis may be associated.

f. VZV vasculitis can cause focal features resulting from cerebral or spinal cord infarction or diffuse leukoencephalitis due to small vessel involvement.

4. Diagnosis. When the characteristic dermatologic eruption occurs, diagnosis of radiculitis is not difficult. In patients with CNS disease, MRI may demonstrate focal or diffuse areas of high-signal intensity on T2-weighted images of the brain or spinal cord. Enhancing focal lesions and meningeal enhancement may also be seen. Diagnosis is confirmed by demonstration of VZV DNA in CSF or tissue or an elevated VZV antibody index in CSF.

5. Management. Patients with HIV and VZV radiculitis should be treated with valacyclovir or famciclovir for 7 to 10 days. Neuralgia can be managed with pregabalin 75 to 150 mg twice a day, or gabapentin 300 to 600 mg three to four times daily. Amitriptyline 25 mg at bedtime may be added and titrated to 100 mg at bedtime.

Patients with VZV encephalitis, meningitis, or myelitis should be treated with IV Acyclovir at 10 mg/kg every 8 hours for 14 to 21 days, adjusted for renal function. Resistance of VZV to acyclovir has been reported and refractory disease should be managed with foscarnet.

6. Outcomes. Most patients with VZV radiculitis achieve resolution of the acute symptoms, although recurrences are common in immunosuppressed individuals and may involve different dermatomes. The prognosis for progressive myelitis and encephalitis varies; however, limited anecdotal data suggest some patients respond to antiviral therapy.

G. CNS tuberculosis.

1. Epidemiology. Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) is the second most common infectious diseases cause of death worldwide after HIV/AIDS and the most common cause of death in HIV-infected patients in resource-limited countries. MTB is transmitted via droplet nuclei, and thus the lungs are the most common organ involved. The organism causes extrapulmonary and disseminated infection more commonly in HIV-infected individuals, especially those with advanced disease (CD4 count <200 cells/mm3). Of all sites of infection, tuberculosis involvement of the CNS is the most severe and has the highest mortality with a poor prognosis despite therapy. TB meningitis (TBM) occurs in about 7% to 12% of individuals with TB, having a subacute or chronic presentation usually preceded by a systemic illness. Individuals may also have mass lesions such as tuberculomas or cerebral abscesses which may evolve more acutely. Up to 20% to 30% of survivors manifest various neurologic sequelae. In the United States, increased risk is associated with intravenous drug use, history of incarceration, homelessness, migration from countries with high MTB prevalence, and close contact with those who have MTB infection.

2. Pathogenesis. MTB belongs to the family of Mycobacteriaceae and is the most common causative agent of TB. MTB enters the body when a person inhales droplet nuclei containing the organism. An individual with intact T-cell–mediated immunity will have limited growth of MTB which helps prevent its spread. Viable bacilli can persist for years as walled-off foci leading to latent TB infection (LTBI). TB can occur in two forms: primary infection or reactivation of latent infection. From either form, the organism can reach the CNS hematogenously and form granulomas or Rich foci in the subependymal layers and later form tuberculomas. In many of these cases, the granulomas rupture and cause meningitis. HIV patients have a 10% per year risk of reactivation of LTBI and progression to active TB disease.

3. Clinical features. Staging of TBM has been established by the Medical Research Council based on mental status at the time of diagnosis. Stage I: Patients are alert with no focal neurologic signs; Stage II: Patients are confused with or without focal neurologic deficits; Stage III: Patients are stuporous or comatose. The most common presentation is meningitis or meningoencephalitis marked by headaches, fevers, anorexia, meningismus, emesis, myalgia, confusion, lethargy, cranial neuropathy, ataxia, seizure or hemiparesis. Patients may also have meningoradiculitis, myelitis, anterior spinal artery infarction, and epidural or intramedullary abscess formation. The mortality and neurologic sequelae of TBM is related to the stage of disease on admission, and the duration of symptoms before presentation.

4. Diagnosis. Early diagnosis and initiation of TB therapy is vital to the management of TBM. Diagnosis is based on clinical presentation, radiographic findings, CSF examination, and response to therapy.

With imaging, MRI is superior to CT at defining lesions in the basal ganglia, midbrain, and brainstem. Neuroimaging with either CT or MRI can demonstrate hydrocephalus (45% to 87%), basilar meningeal enhancement (23% to 38%), infarct (20% to 38%), and tuberculomas (12% to 16%). Neuroimaging may show brain abscesses that may be difficult to distinguish from toxoplasmosis or CNS lymphoma. MRI of the spine may demonstrate abscesses and vertebral body collapse in patients with meningitis or myelitis.

CSF typically reveals a mixed or predominantly lymphocytic pleocytosis, elevated protein, and low glucose. Detection of MTB in the CSF is the gold standard for diagnosis of TBM. However smears for acid-fast bacteria (AFB) are rarely positive, and the growth of the organism is slow in culture. CSF culture may be negative in up to one-third of cases, although in some reports, diagnostic yield of AFB staining can increase up to 87% when four serial CSF examinations were performed. Detection of MTB DNA by PCR and MTB antigen assays provide more rapid detection in CSF. Diagnosis of tuberculomas and abscesses may require biopsy with demonstration of granulomas and AFB on pathology along with positive culture for MTB.

5. Management.

a. TB therapy. If there is a strong clinical suspicion of TBM, then therapy should not be delayed until a microbiologic diagnosis can be confirmed, as outcomes are dependent on the stage of disease at which therapy is initiated. Patients should be started on “Intensive Phase” therapy, which consists of a four-medication regimen of isoniazid (INH), rifampin (RIF), pyrazinamide (PZA) and a fourth agent, either ethambutol (ETB) or streptomycin (SM), for at least 2 months. Pyridoxine is added for patients taking INH. Drug susceptibility testing to first-line TB medications (INH, RIF, PZA, ETB) should be performed on all patients with MTB disease as these results impact therapeutic regimens. Upon completion of the “Intensive Phase” the “Continuation Phase” of therapy includes INH/RIF for pan-sensitive TB for 9 to 12 months.

Multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) is increasingly more common and refers to an isolate resistant to INH and RIF. Extensively drug-resistant TB (XDR-TB) refers to an isolate resistant to INH, RIF, Fluoroquinolones (FQ), and Aminoglycosides (AG). Patients with either MDR or XDR TB require more complex and prolonged therapy and should be referred to a specialist for care.

b. Corticosteroids. Adjunctive use of corticosteroids in TBM has been shown to improve survival. The Panel on Opportunistic Infections in HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents recommends using tapering doses of dexamethasone in the treatment of TBM. In patients with TBM, dexamethasone 0.3 to 0.4 mg/kg/day or prednisone 1 mg/kg/day should be added for the first 3 weeks and then tapered over the next 3 to 5 weeks. IRIS is not uncommonly seen with reversal of immune suppression following cART (see Section J under Opportunistic Infections.).

c. ART. Treatment of TB and HIV can be challenging due to problems of noncompliance from high pill burden, medication side effects from both therapies, drug–drug interactions among agents, and the development of IRIS. Due to the numerous considerations which must be taken into account the Panel on Opportunistic Infections in HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents currently recommends that in ART-naive patients with a CD4 count <50 cells/mm3, ART should be initiated within 2 weeks of diagnosis, and by 8 to 12 weeks for all others. There are no clear guidelines for when to initiate ART in HIV-infected individuals with TBM. Thus, caution must be taken when initiating ART in patients with TBM, particularly those with low CD4 counts as they must be monitored closely.

6. Outcomes. The mortality of HIV-associated TBM often exceeds 50% and is related to the degree of immune suppression. Patients with TBM need follow-up CSF studies to ensure there is not persistent infection. Tuberculomas can be followed with serial imaging in the absence of life-threatening mass effect. Lesions that enlarge despite therapy should be reevaluated and considered for biopsy to detect resistant organisms or concurrent opportunistic processes.

H. Neurosyphilis.

1. Epidemiology. Syphilis is a sexually transmitted infection caused by Treponema pallidum. The disease is divided into stages based on clinical findings, which guides treatment and follow-up. It is associated with increased risk of sexual acquisition and transmission of HIV. Although not strictly an opportunistic pathogen, overlapping risk factors and a potentially more aggressive course make it an infection of particular concern in patients with HIV infection. Increased frequency of CNS involvement and occasional failure of conventional therapy with emergence or recurrence of neurosyphilis despite standard courses of penicillin have been reported.

2. Pathogenesis. Neurosyphilis occurs when T. pallidum invades the CSF. This can occur during any stage of disease as CSF abnormalities are common in individuals with early syphilis even in the absence of neurologic findings. Invasion of the CSF with T. pallidum does not always cause persistent infection and in some cases spontaneous resolution may occur without an inflammatory response.

3. Clinical features. All persons with HIV infection and syphilis should undergo a careful neurologic exam and those with abnormal neurologic signs or symptoms should undergo CSF examination. In the absence of neurologic symptoms, CSF examination has not been associated with improved clinical outcomes and is not recommended. The exception to this is patients with tertiary syphilis who should also receive a CSF exam prior to initiation of therapy to see if they have neurosyphilis.

Neurosyphilis can be categorized into early and late forms. Early forms of the disease include asymptomatic neurosyphilis, symptomatic meningitis, ocular syphilis, otosyphilis, and meningovascular syphilis. Late forms of disease include general paresis and tabes dorsalis.

Clinical evidence of neurologic involvement can be meningitis, encephalitis, cognitive dysfunction, motor or sensory dysfunction, cranial nerve palsies, signs or symptoms of stroke, motor or sensory deficits, and visual or auditory symptoms. Syphilitic uveitis or other ocular manifestations (neuroretinitis and optic neuritis) can also be associated with neurosyphilis, thus a CSF examination should be performed in all cases of ocular syphilis even if there are no neurologic findings.

4. Diagnosis. Early syphilis is best diagnosed by using darkfield exam and tests to detect T. pallidum directly from the lesion exudate or tissue. A diagnosis of syphilis requires two tests: a non-treponemal test (i.e., Venereal Disease Research Laboratory [VDRL] or Rapid Plasma Reagin [RPR]) and a treponemal test (i.e., fluorescent treponemal antibody absorbed [FTA-ABS] tests, the T. pallidum passive particle agglutination [TP-PA] assay, various enzyme immunoassays [EIAs], chemiluminescence immunoassays, immunoblots, or rapid treponemal assays). Use of only one type of serologic test can lead to false-negative or positive results.

The diagnosis of neurosyphilis is complex and depends on the combination of CSF tests (cell count, protein, and reactive VDRL), in the presence of reactive serologic tests and neurologic abnormalities. CSF leukocyte count is usually elevated in patients with HIV, so a cutoff of >20 WBC/mm3 is recommended to improve the specificity of neurosyphilis diagnosis. The CSF-VDRL is specific but insensitive. If it is negative, and there is a high clinical suspicion for neurosyphilis additional evaluation using the FTA-ABS testing on the CSF should be considered.

5. Management. Neurosyphilis should be treated with intravenous aqueous crystalline penicillin G 18 to 24 million units per day, administered as 3 to 4 million units every 4 hours (or as a continuous infusion) for 14 days. An alternative regimen, is 2.4 million units of intramuscular procaine penicillin G once daily plus probenecid 500 mg orally four times a day for 14 days. This regimen can be used in patients who are thought to be compliant and not allergic to sulfa medications. Benzathine penicillin, 2.4 million units IM once a week for three doses can be considered after completion of treatment for neurosyphilis.

6. Outcomes. Although initial response to treatment is good, the risk of recurrent neurosyphilis is increased in the setting of HIV infection. If initial CSF examination demonstrates pleocytosis, a repeat CSF examination should be performed every 6 months until the cell count is normal. Follow-up CSF examination should also be used to evaluate changes in CSF-VDRL or protein; however, changes to these parameters occur more slowly than the cell count. If the cell count has not decreased after 6 months or if the CSF cell count or protein is not normal after 2 years, retreatment should be considered. Additionally new onset of neurologic symptoms should prompt evaluation for neurosyphilis.

I. Other OIs. Numerous other OIs have been described in HIV-infected patients. A more complete compilation is beyond the scope of this chapter. More extensive reviews are contained in the references below.

J. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome.

1. Epidemiology. IRIS is a potentially life-threatening condition that occurs in approximately 35% of patients following initiation of ART. It is a potential consequence of rapid restoration of the patient’s immune system in the setting of improving HIV disease markers (i.e., HIV VL and CD4 count). IRIS is characterized by a paradoxical worsening in the patient’s clinical condition. Some cases occur in the absence of OIs and are presumed to be an inflammatory response to HIV-related antigens. In other cases, a resident OI may be unmasked by initiation of ART and the vigorous immune response which follows, whereas in other instances, an initial improvement in an OI may be followed by clinical worsening. In this scenario it may be difficult to distinguish between treatment failure of the OI versus IRIS.

CNS IRIS is rare and has an incidence of 0.9% to 1.5%. It can be seen in the setting of AIDS-related OIs, such as PML, CMV, cryptococcal disease, CNS tuberculosis, or toxoplasmosis. Individuals who are ART naive, have a low CD4 T-cell count, high HIV VL, and show rapid improvement in immunologic and virologic markers in response to ART appear to be at greatest risk for IRIS. A majority of cases occur within the first 8 weeks of initiation of ART and likelihood of IRIS may be increased when ART is initiated in close proximity to treatment for an OI. This can become difficult when initiating ART in a patient with a CNS OI and such patients should be monitored closely for IRIS.

2. Pathogenesis. The pathogenesis of IRIS remains unclear. Following initiation of ART there is a rapid recovery of memory T cells. These lymphocytes penetrate peripheral nonlymphoid sites, recognize previously encountered antigens and mount an inflammatory response. Most paradoxical inflammatory responses are against opportunistic pathogens already present when ART is initiated. Pathologic reports of CNS IRIS most commonly have identified CD8+ lymphocytic infiltration from the perivascular space along with activated macrophages.

3. Clinical features. Patients with CNS IRIS may present with signs and symptoms consistent with an infectious or inflammatory condition temporally related to initiation of ART. Patients may develop recurrence of the initial symptoms associated with their infection or may develop new inflammatory symptoms such as fever, enlarged lymph nodes, headache, AMS, meningitis, encephalitis, or cranial nerve palsies after initiation of ART.

4. Diagnosis. A diagnosis of IRIS requires exclusion of recurrent or new concurrent infection or neoplasm to explain the clinical syndrome. In cases where biopsy is pursued, a vigorous CD8+ inflammatory response in the absence of active infections suggests the diagnosis. MRI may show enlarged space enhancing lesions with edema and mass effect suggestive of an inflammatory response in patients with CNS parenchymal disease. Individuals should be suspected of having CNS IRIS when they present with the following:

a. Rapid deterioration of clinical and neurologic status following initiation of ART

b. Decrease of HIV RNA greater than 1 log

c. Clinical, laboratory, and radiologic signs and symptoms concerning for inflammation

d. Lack of correlation between symptoms and a newly acquired infection, a previously present OI, or drug toxicity.

5. Management. There are no RCTs addressing management of IRIS. Stopping ART is not recommended as resumption of HIV viral replication will allow for disease progression. Both spontaneous resolution and resolution associated with corticosteroid therapy have been reported. Current practice favors high-dose steroids for patients with severe neurologic symptoms and IRIS. Steroids may be required for several weeks or months and should be gradually tapered to prevent rebound inflammation on withdrawal.

6. Outcomes. IRIS can affect any organ system in the body, however when it affects the CNS it can cause significant morbidity and mortality. Mortality rates range from 5% to 15% as it can be difficult to manage the inflammatory response in the setting of an OI. Ultimately, if the inflammatory response can be contained as the patient’s immune system recovers, the patient’s long-term outcome will be improved.

Key Points

• HIV may involve the CNS directly or through causing opportunistic diseases

• Even on effective ART, subtle findings of HAND may be present in over half of patients

• In cryptococcal meningitis, elevated ICP must be aggressively managed

• A 2-week trial of therapy in a toxoplasma seropositive patient with encephalitis and compatible imaging may obviate the need for brain biopsy

• Detection of Epstein–Barr virus DNA by PCR in CSF strongly supports the diagnosis of primary CNS lymphoma

• Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) can be diagnosed with compatible clinical presentation, neuroimaging and detection of JC Virus DNA in CSF or tissue

• Nervous system involvement by CMV is uncommon and can present as encephalitis, radiculitis, myelitis, or multifocal neuropathy

• If TB is highly suspected as a cause of meningitis, therapy should commence before diagnosis can be confirmed

• Invasion of the nervous system by T. pallidum (syphilis) occurs in early stages of the disease but may resolve spontaneously

• The immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) follows initiation of ART and is characterized by paradoxical worsening either of HIV itself or an OI.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree