NORMAL PHYSIOLOGIC CHANGES IN PREGNANCY

A. Cardiovascular.

1. Increase of 30% to 50% in cardiac output and blood volume with singleton pregnancy (70% with twins)

2. Midpregnancy decrease in blood pressure by 5 to 10 mm Hg systolic and 10 to 15 mm Hg diastolic.

B. Pulmonary.

1. Increase of 20% to 30% in minute volume.

2. Increase in respiratory rate and partially compensated respiratory alkalosis.

C. Renal.

1. Increase of 30% to 50% in renal blood flow.

2. Decreased serum level of blood urea nitrogen and creatinine (because of increased renal clearance). Serum creatinine in mid-late pregnancy should be <1.0 mg%.

D. Gastrointestinal.

1. Decreased motility as a result of progesterone-mediated decreases in smooth muscle activity.

2. Elevated alkaline phosphatase level (placental). No pregnancy-associated changes in any other liver function tests.

3. Increased cytochrome P-450 activity.

E. Hematologic.

1. Decreased hematocrit (20% to 30% increase in red blood cell (RBC) volume, but 30% to 50% increase in blood volume).

2. Increased white blood cell count; decreased platelet count.

F. Coagulation factors.

1. Increased levels of plasminogen, fibrinogen, and factors VII, VIII, IX, and X.

2. No change in factor V, antithrombin, or platelet adhesion.

3. Thrombophilias (e.g., antiphospholipid antibodies, protein C and S deficiency, factor V Leiden) are more likely to produce thromboembolic complications.

G. Connective tissue. Thickening and fragmentation of reticular fibers with mild hyperplasia of smooth muscle cells.

H. Hormonal changes. Progressive increase in estrogens and progesterone until delivery.

I. Serum osmolality. Decreases from early in gestation, with resultant increase in extracellular fluid volume.

J. Neurologic. Increase in pituitary size; slight decrease in brain volume that returns to baseline postpartum.

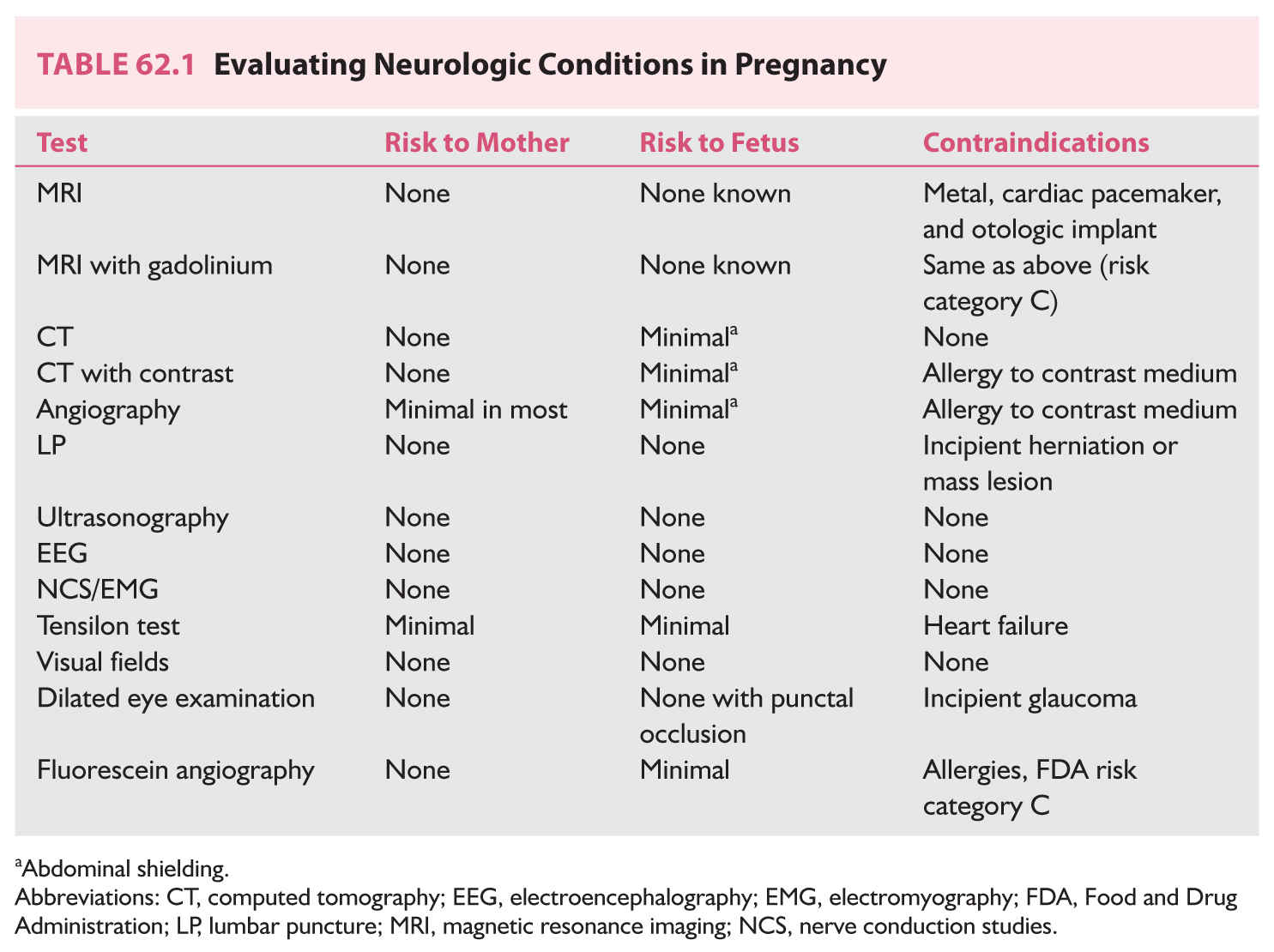

K. Evaluating neurologic conditions in pregnancy (Table 62.1).

L. US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) risk factor classification of drugs in pregnancy.

1. Class A. Controlled studies show no risk to fetus in the first trimester; fetal harm is remote.

2. Class B. No controlled studies have been completed, but there are no known risks.

3. Class C. Studies on animals may show effects on fetuses, but no results of controlled studies are available. The drug can be used if the risk is justified.

4. Class D. There are risks, but the drug may be used if serious disease or life-threatening conditions exist.

5. Class X. Human and animal studies show risk. The risk of use outweighs any benefit.

SEIZURE DISORDERS IN PREGNANCY

A. Frequency. One percent of the population, about 500,000 women of childbearing age.

1. In an unselected population, frequency is 7 to 8 per 1,000 deliveries. This is about 25,000 deliveries per year, or approximately one every 20 minutes.

2. Some antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), particularly phenobarbital, phenytoin, and carbamazepine, lower the efficacy of some oral contraceptives in some individuals, making pregnancy more likely.

B. Heredity.

1. About 2% to 5% of women have genetic susceptibility probability of vertical transmission if either parent has idiopathic epilepsy. Relatively higher if the parent is the mother; relatively lower if the parent is the father.

2. No significant transmission if disease is acquired.

C. Course of disease in pregnancy.

1. The best figures for disease activity during pregnancy include the following:

a. Improved, 22%

b. Exacerbated, 24% (most likely to occur in the first trimester)

c. No change, 54%

2. Postulated mechanisms for changes in frequency during pregnancy include the following:

a. Physiologic

(1) Hormonal (estrogens decrease and progestins increase seizure threshold)

(2) Metabolic (increased cytochrome P-450 activity)

b. Sleep deprivation

c. Noncompliance (e.g., fear of birth defects from taking medications)

d. Pharmacokinetic changes in drug levels caused by: impaired absorption, increased volume of distribution, decreased albumin concentration, reduced plasma protein binding, and increased drug clearance

e. Folate supplementation can reduce anticonvulsant levels

f. Stress and anxiety decrease seizure threshold, making seizures more likely.

g. Alcohol or other drug use makes seizures more likely.

3. Seizure frequency during pregnancy does not correlate with maternal age, seizure type, drug regimen, and seizure frequency in previous pregnancies.

4. Fetal risks with generalized convulsive seizure include the following:

a. Physical injury from maternal abdominal trauma

b. Hypoxic–ischemic injury because of maternal hypoxia

D. Therapeutic options.

1. Pharmacologic.

a. Be certain of the diagnosis, especially with new-onset seizures in pregnancy.

b. Be familiar with and use the few drugs that are the most effective for the various types of seizures.

2. Surgery in general should be addressed before or after pregnancy.

3. General.

a. Maintain good daily habits (regularly scheduled meals, adequate sleep, and minimize stress).

b. Avoid alcohol and sedatives.

c. Avoid hazardous situations.

d. Avoid ketogenic diet.

E. Drug dosages, plasma levels, and clinical management.

1. AED levels decline during pregnancy in almost all women. This does not necessarily equate with a need to increase dosage, unless seizures are not controlled.

a. Free (non–protein-bound) drug level equates best with clinical status (seizure control and side effects) and should be obtained in pregnancies complicated by persistent or recurrent seizures or side effects.

b. Total drug level (the usual laboratory result) sufficient if the patient has good clinical control.

c. With the exception of valproic acid, the average decline in free levels is less than that for total levels.

2. Frequency of measurement of levels.

a. Ideally, preconceptional total and free levels should be obtained and optimized.

b. Obtain non–protein-bound (free) levels every trimester (every 3 months), and again 4 weeks before term when seizure types do not interfere with activities of daily living and the epilepsy is well controlled.

c. Obtain monthly free levels when uncontrolled seizures interfere with activities of daily living during the year before conception, previously controlled seizures recur during pregnancy, seizures are controlled but total drug levels decrease >50% on routine screens, troublesome or disabling side effects develop, and lack of compliance is suspected or confirmed.

d. Always check levels postpartum and adjust dosage because levels often increase as the physiologic effects of pregnancy resolve within 10 to 15 days after delivery.

3. Changing drug dosage.

a. Reasons not to change dosage.

(1) Total drug levels are declining in a woman with well-controlled seizures, unless there are >30% decline in free levels and a history of poor control.

(2) A woman taking two or more AEDs discovers that she is pregnant (the time to change to monotherapy is before conception).

(1) Increased numbers of tonic–clonic seizures

(2) Complex partial or other seizure types that interfere with activities of daily life and the patient wants better control

(3) Troublesome or disabling side effects

c. Discontinuation of AED therapy should ideally be accomplished before conception but can be considered cautiously during pregnancy if a patient has been seizure-free for more than 2 years, has normal findings on neurologic examination, normal electroencephalographic findings, no structural brain disorder, and no history of prolonged convulsive seizures

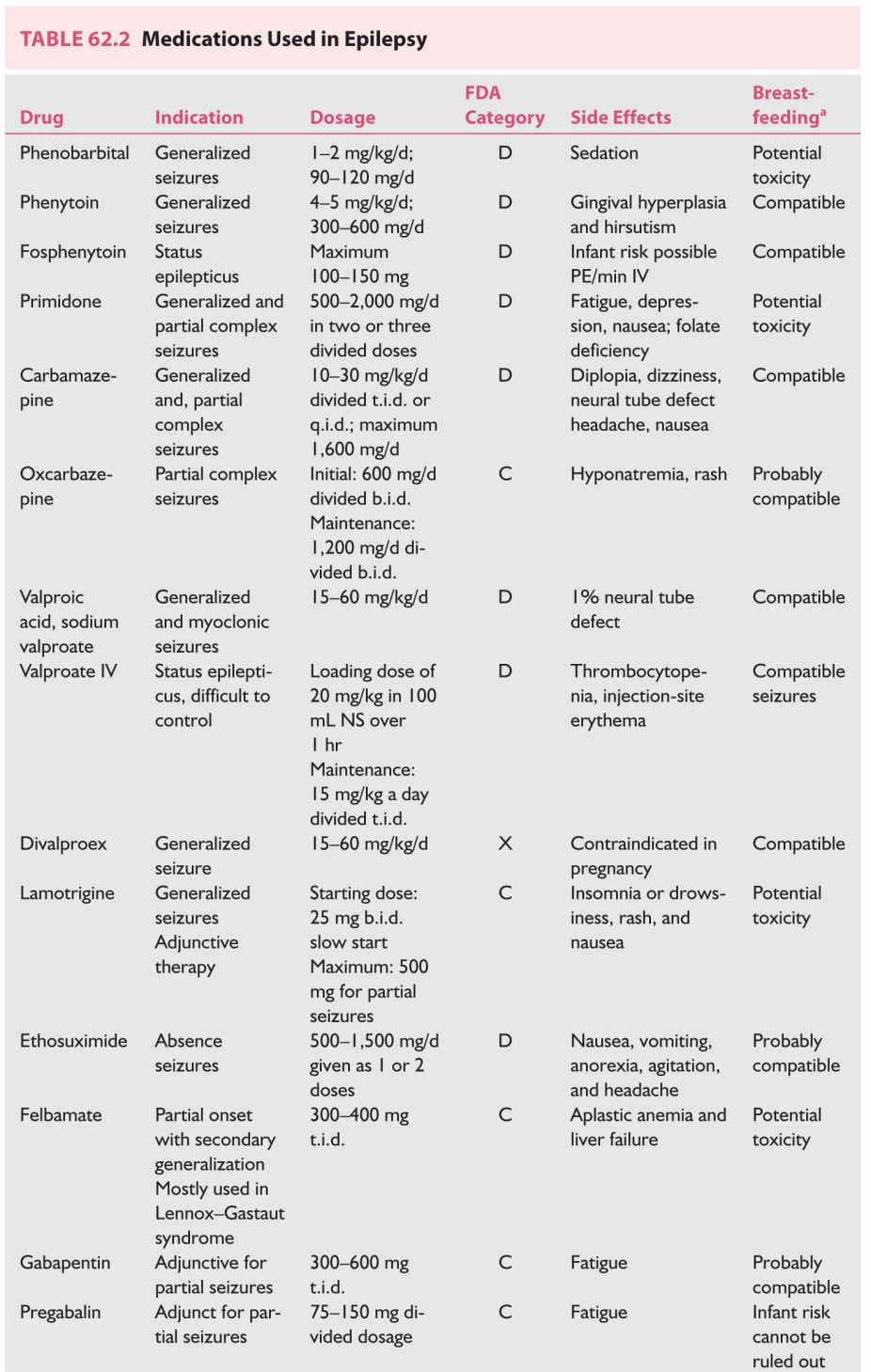

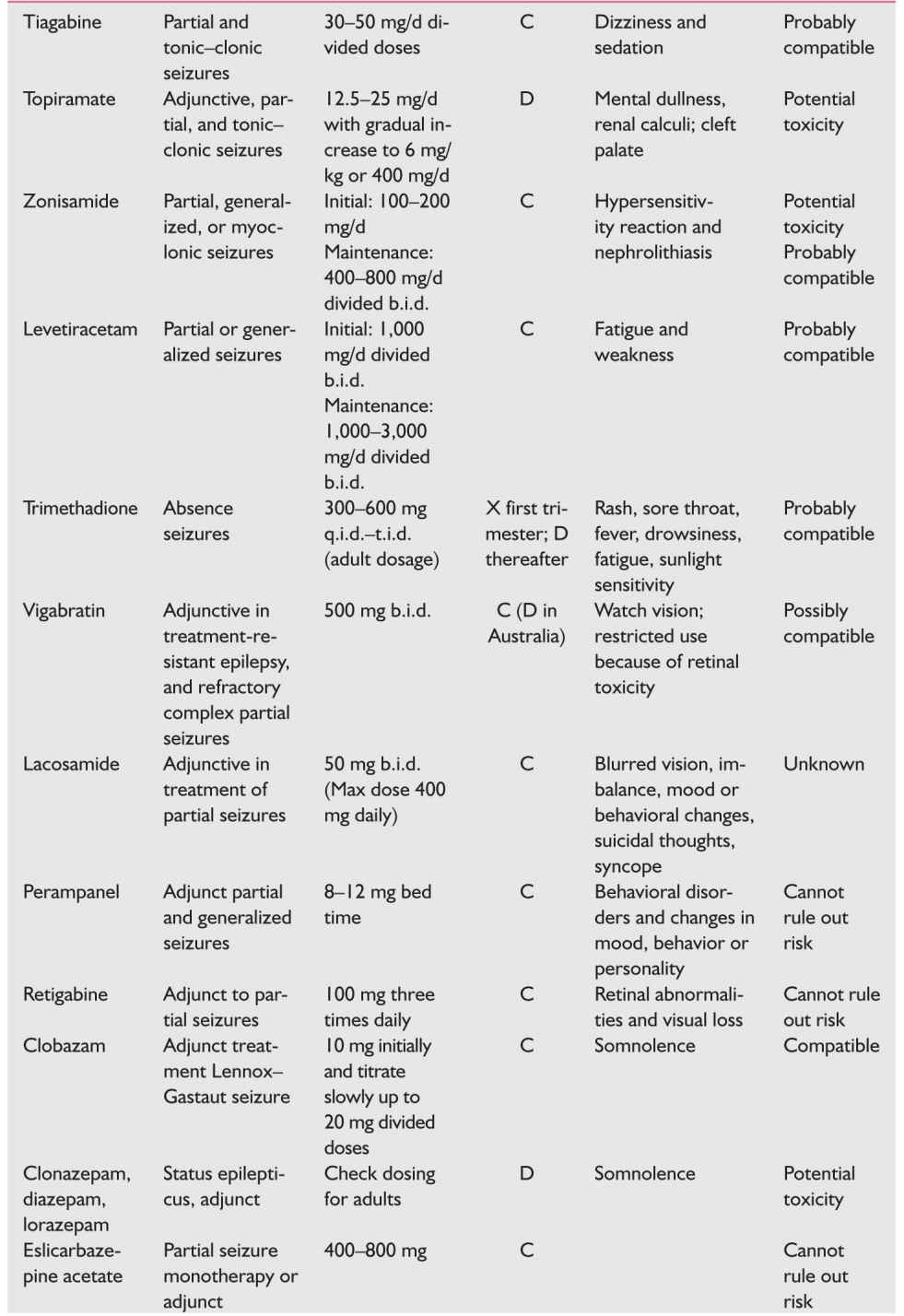

4. AEDs used in pregnancy (Table 62.2); breast-feeding while taking AEDs does not appear to affect cognition.

5. Other drugs to add or consider for patients with epilepsy

a. Folic acid.

(1) Requirements may be further increased because of malabsorption, competitive metabolism, and increased hepatic metabolism.

(2) Increased supplementation may precipitate seizures by lowering anticonvulsant levels.

(3) Best advice is to maintain usual supplementation.

(4) Compelling evidence links the folic acid antagonism properties of AEDs to relatively increased risk of fetal neural tube defects in women taking anticonvulsants during the first trimester (neural tube defects form, or do not form, 26 to 28 days after conception). Women of reproductive potential should take continuous folic acid supplementation (400 mg/day) whether or not they are considering pregnancy.

b. Vitamin K should be administered (10 mg by mouth daily) to all pregnant women receiving AEDs beginning 4 weeks before expected delivery until birth to minimize the risk of neonatal hemorrhage. If a woman has not received vitamin K before delivery, consideration should be given to parenteral vitamin K administration.

c. Vitamin D is not routinely supplemented.

6. Birth defects in infants of epileptic mothers

a. Major birth defects in healthy pregnant women = 2% to 3%. In epileptic women on monotherapy = 3.2% to 7.8%. In epileptic women on polytherapy = 6.0% to 9.3%.

b. Should be discussed with all epileptic women of reproductive age, irrespective of whether or not they are planning pregnancy (50% of pregnancies are unplanned)

c. Other factors that may explain the increased incidence of anomalies in infants of epileptic mothers are as follows:

(1) Increased incidence of anomalies in infants of epileptic mothers not taking AEDs. The only anomalies that are more common in phenytoin-exposed fetuses are hypertelorism and digital hypoplasia.

(2) Increased incidence of characteristic malformations in infants of epileptic fathers, described as being intermediate between treated and untreated epileptic mothers

(3) A specific metabolic defect (epoxide hydrolase deficiency) more common in persons with epilepsy may predispose to damage in some cases. Autosomal codominant and increased fetal anomalies

(4) Epilepsy may represent an underlying genetic disease.

(5) The defects may result from an AED-mediated relative folate deficiency. (Folate antagonists are known abortifacients and teratogens; see discussion above.)

7. AED teratogenesis should be discussed with all women with epilepsy of reproductive age, particularly because up to half of all pregnancies are unplanned.

a. Fetal anticonvulsant syndrome occurs in 3% to 5% of epileptic women and can occur in association with use of any anticonvulsant medication. The relative risk is dose dependent. This syndrome is being seen with decreasing frequency as fewer women receive polytherapy and more receive monotherapy.

(1) Craniofacial (cleft lip and palate) and digital dysmorphic changes

(2) Growth deficiency

(3) Microcephaly

(4) Cardiac defects

(5) Intellectual disability

b. AEDs and neural tube defects.

(1) Risk is 1% to 2% for valproic acid and slightly less for carbamazepine. It is <1% for other anticonvulsants. However, these risks are >0.1% population-wide risk in the United States.

(2) The relative risk is dose related.

(3) If the medications are necessary for seizure control, the patient should be offered maternal serum α-fetoprotein and ultrasound screening.

c. Trimethadione is clearly teratogenic and is contraindicated in pregnancy.

8. Breast-feeding.

a. Most AEDs cross into breast milk, although at low levels; the higher the protein binding of the AED, the less that is passed into breast milk. Recent studies show no cognitive change in babies breast fed while mother takes AED.

b. Contraindications to breast-feeding include poorly controlled maternal seizures and rapid somnolence on the part of an initially hungry infant, which suggests a drug effect.

F. Onset of seizures during pregnancy: differential diagnosis.

1. Rule out eclampsia. The most common multisystem disease in late pregnancy is preeclampsia or eclampsia.

2. Cortical venous thrombosis, especially late in pregnancy and in the immediate puerperium.

3. Tumors are especially likely to manifest in the first trimester because this is when the pregnancy-associated increase in extracellular fluid begins. Meningioma tends to expand during pregnancy (response to the progressive increases in estrogen and progesterone).

4. Intracranial hemorrhage.

5. Gestational epilepsy is a diagnosis of exclusion and represents only a small fraction of all women who have initial seizures while pregnant.

6. Drugs or toxins

G. Status epilepticus during pregnancy (follow guidelines for nonpregnant patients).

1. Less than 1% of all pregnant epileptic women

2. Not an indication for termination of pregnancy

3. Management should follow standard treatment of status epilepticus. Hospitalize, securing the airway, intravenous (IV) access for normal saline solution and B vitamins, baseline laboratory studies including electrolytes, complete blood count, glucose, calcium, and arterial blood gases. Maternal and fetal vital signs, including electrocardiography (ECG) and fetal heart rate monitoring. In addition, administer the following:

a. Glucose bolus (50 mL of D50)

b. Thiamine (100 mg intramuscularly or intravenously)

c. Begin lorazepam (0.1 mg/kg IV, not to exceed 2 mg/minute) or diazepam (5 to 15 mg IV in 5 mg boluses) and fosphenytoin (150 mg/minute) or phenytoin (10 to 20 mg/kg IV, not to exceed 50 mg/minute, with ECG and blood pressure monitoring, administered in non-glucose-containing fluids).

d. If seizures persist, intubate and begin either phenobarbital (20 to 25 mg/kg IV, not to exceed 100 mg/minute). Alternatives include midazolam, propofol, levetiracetam, or IV valproic acid (if absolutely necessary).

e. If seizures still persist, institute general anesthesia with halothane and neuromuscular junction blockade. (See Chapters 42 and 43.)

HEADACHE

A. The most common headache diagnoses are as follows:

1. Migraine (with or without aura) occurs in 10% to 20% of women of childbearing age. Unilateral or bilateral throbbing headaches associated with photophobia, phonophobia, nausea, or vomiting may be exacerbated by activity.

2. Tension-type headache is very common. Mild-moderate headache, without nausea and vomiting, may be relieved by activity.

B. Genetics of migraine. Migraine is more common in affected families. Hemiplegic migraine is autosomal dominant associated with three different gene loci affecting ionic channels; however, there are multiple polymorphisms associated with migraine.

C. Course of migraine in pregnancy.

1. The condition of most women with migraine improves when they are pregnant. This is especially true with menstrual migraine and migraine whose onset was at menarche. If migraines do not improve after the first trimester, it is likely to continue.

2. About 10% to 20% of headaches worsen or have the initial onset during pregnancy, usually in the first trimester. Many of these may be migraine aura without headache.

3. Migraineurs have no increased risk of complications during pregnancy, but headaches usually recur near term and in the puerperium.

4. Multiparous migraineurs may have an increase in headaches in the third trimester, whereas nulliparous women report less headache activity in pregnancy and the puerperium.

D. The differential diagnosis of headache or migraine occurring for the first time in pregnancy includes the following:

1. Severe preeclampsia/eclampsia—headache with hypertension should bring this diagnosis to the forefront.

2. Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (RCVS)

3. Cerebral venous thrombosis

4. Stroke (carotid or vertebral artery dissection)

5. Intracranial hypertension [increased intracranial pressure (ICP)] or intracranial hypotension or hypovolemia

6. Intracranial hemorrhage

7. Brain tumor

8. Thrombocytopenia

E. Therapeutic options.

1. Nonmedication treatment.

a. Adequate sleep, fluids, regular meals, and exercise

b. Avoidance of dietary and environmental trigger factors

c. Biofeedback, relaxation therapy, mindfulness, massage, physical therapy, and heat or ice packs

2. Acute medication treatment principles.

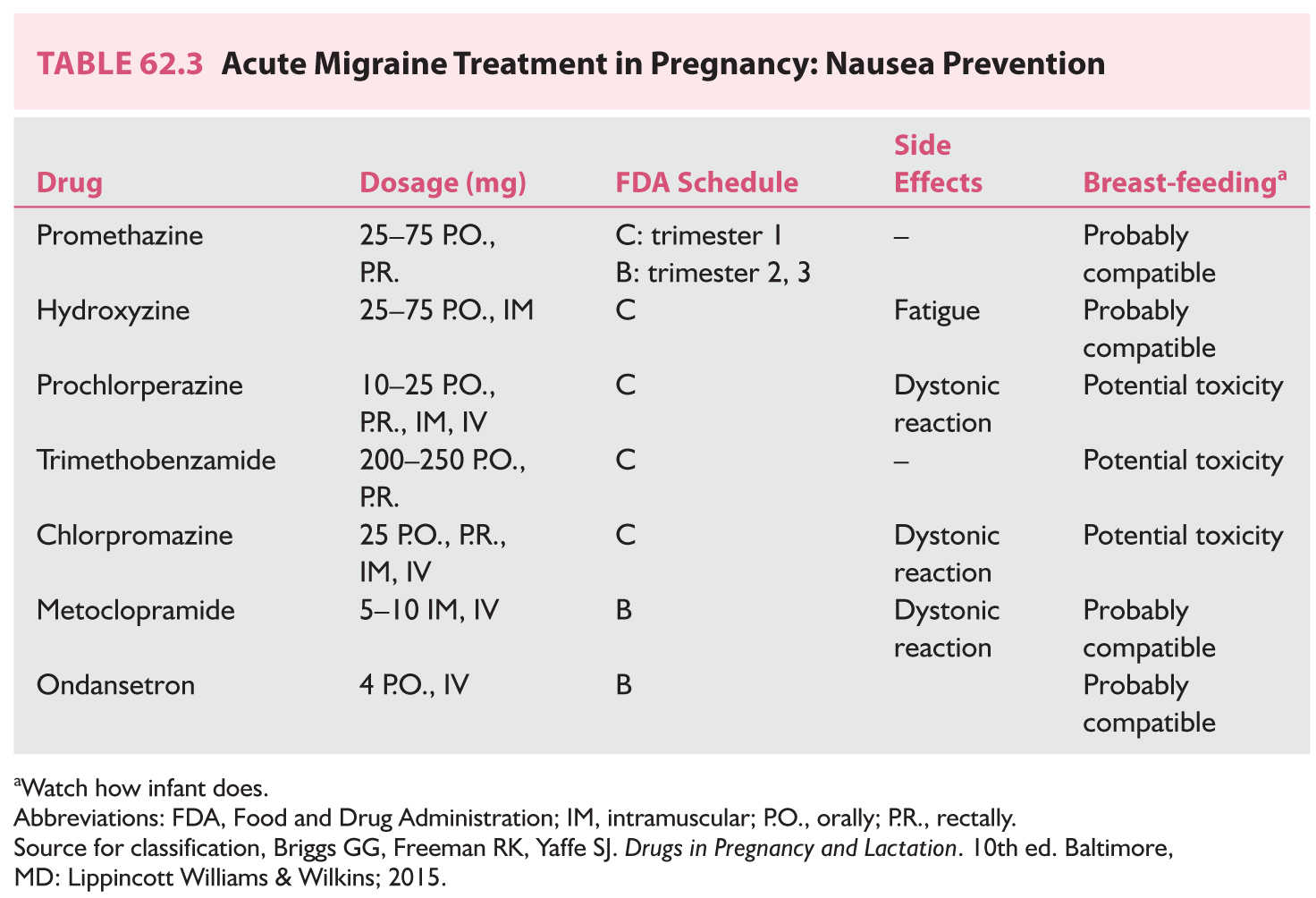

a. Prevention of nausea (Table 62.3)

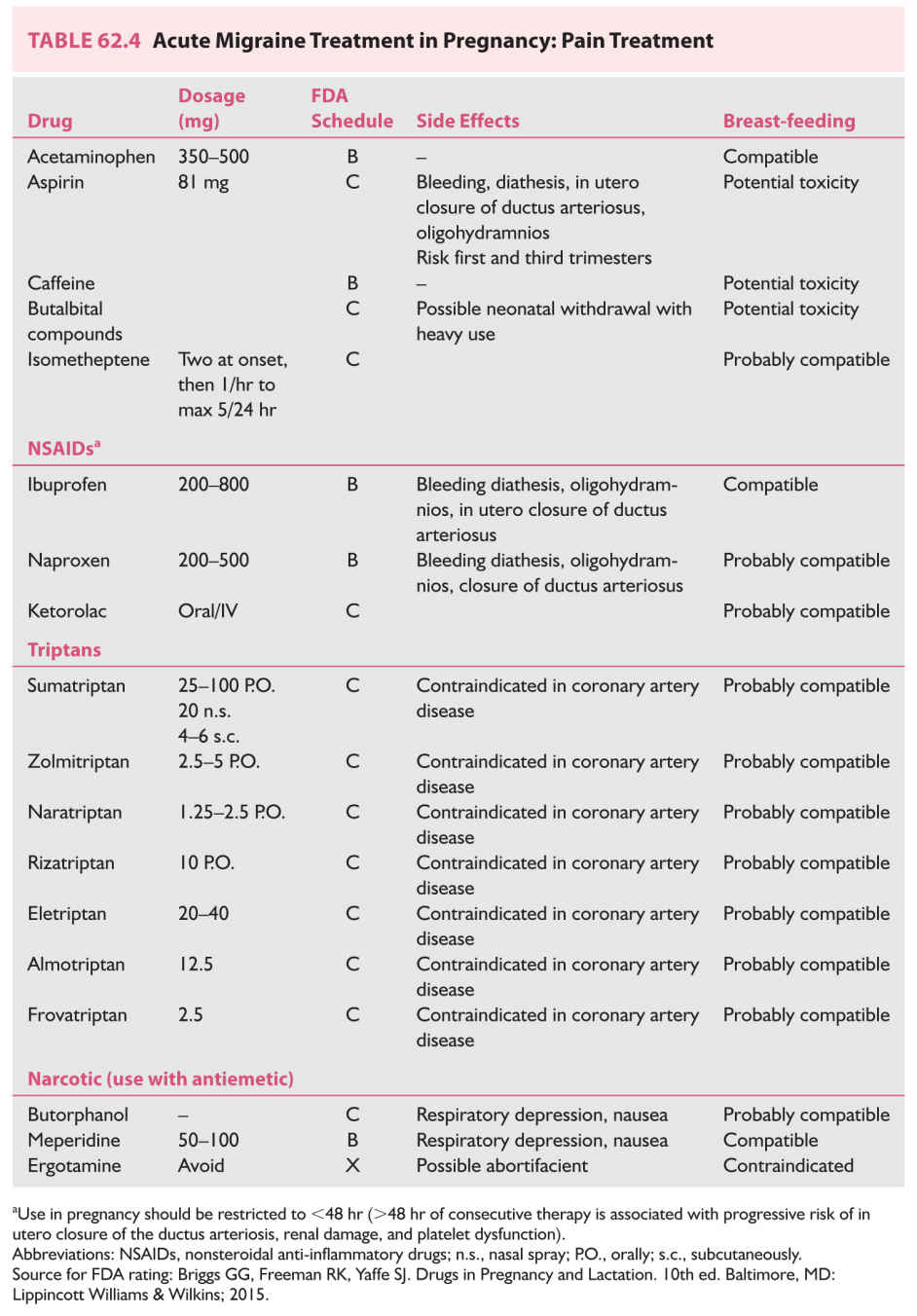

b. Management of pain (Table 62.4)

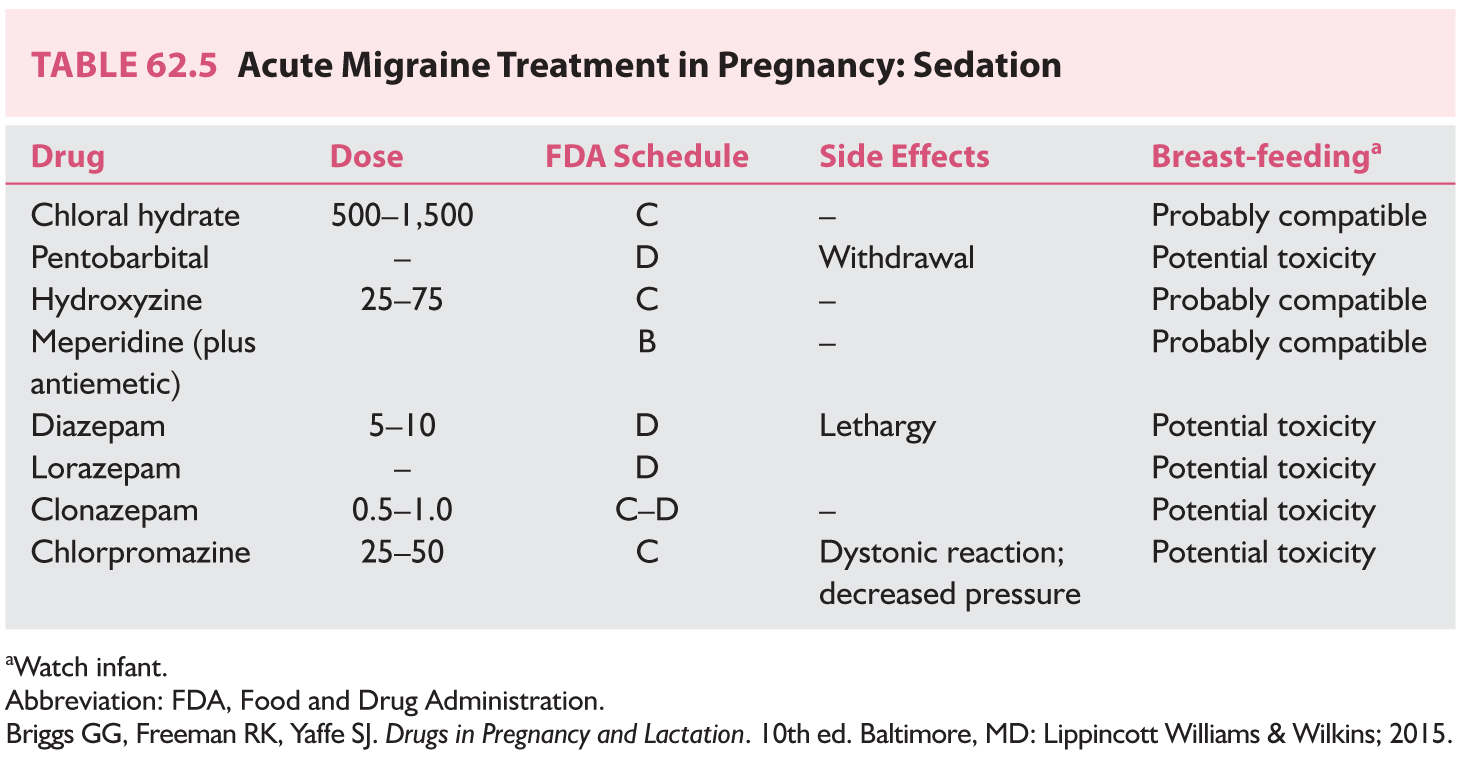

c. Sedation (Table 62.5)

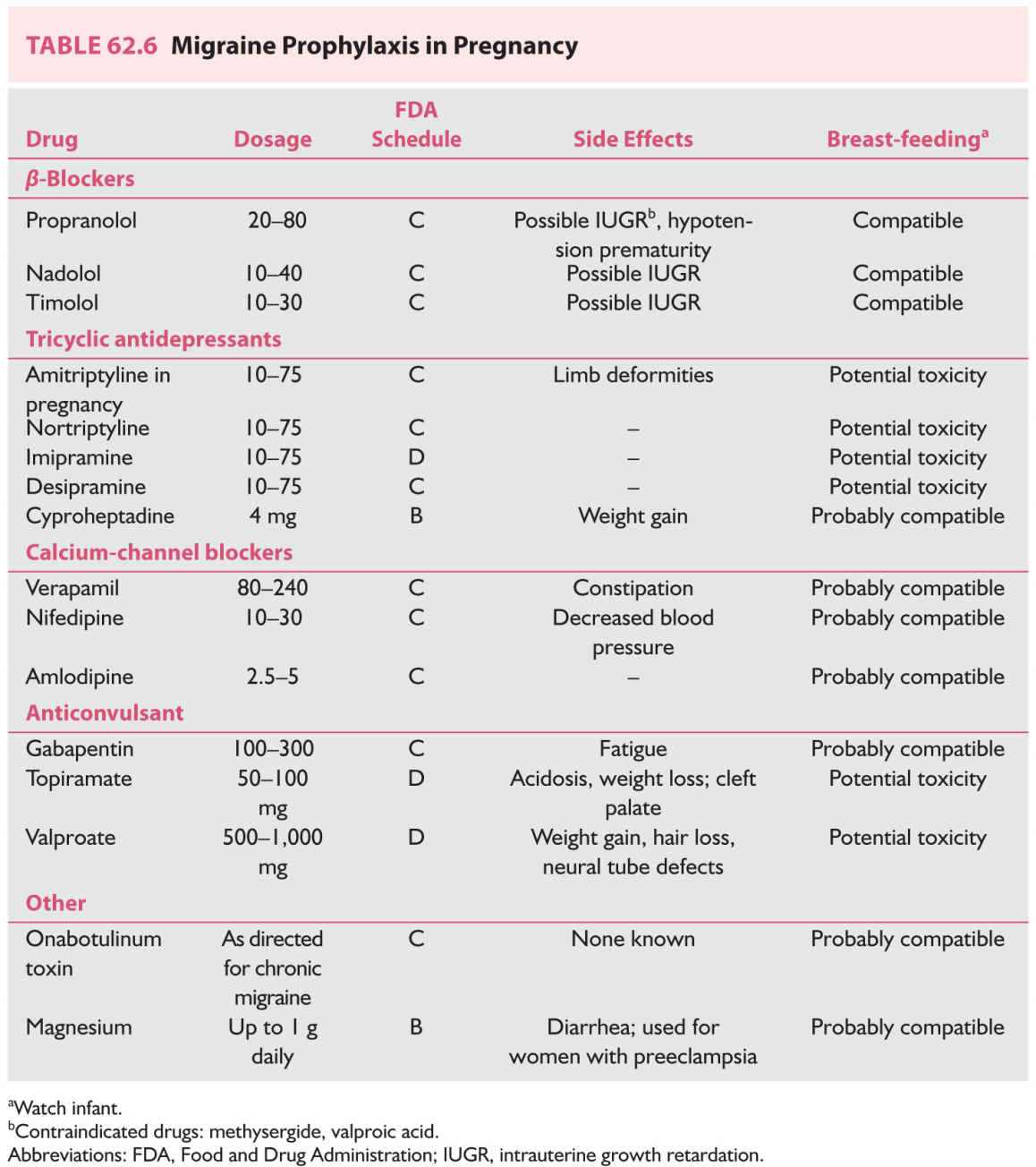

3. Prophylactic treatment. In general, avoid daily medication for headaches, but if headaches are too severe or interfere excessively with life, daily treatment may be needed. In general, monotherapy should be attempted. The lowest dosage should be encouraged (Table 62.6).

TUMORS

A. Incidence.

1. Probably 100 primary brain tumors per year nationwide

2. Pregnancy does not increase the risk of brain tumors but does increase the likelihood of symptoms, primarily because of the decrease in serum osmolality.

3. The types of tumors are identical to those observed in nonpregnant women of the same age, primarily glioma (32%), meningioma (29%), acoustic neuroma (15%), and others (24%).

4. Metastatic tumors are relatively more common, with lung, breast, and gastrointestinal tract being the most common primary sites.

B. Clinical features include headache, nausea and vomiting, papilledema, focal deficits, or seizures.

C. Diagnosis is made by imaging: magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with contrast enhancement (gadolinium) or computed tomography (CT) with contrast enhancement (Table 62.1).

D. Treatment.

1. Surgery is the treatment of choice for most lesions. If the woman is clinically stable, meningiomas and low-grade malignant gliomas can be managed expectantly until after delivery. However, malignant tumors should be resected promptly.

2. Dexamethasone (risk factor C)

a. Dosage: 6 mg every 6 hours or 4 mg every 4 hours

b. Problems: gastrointestinal; Cushingoid changes with prolonged use

3. Mannitol (risk factor C) for acute brain swelling

E. Pituitary tumors.

1. Course of disease.

a. Microadenoma is rarely symptomatic (5%).

b. Macroadenoma is symptomatic in 15% to 35% of cases.

2. Serial visual field evaluation must be performed for macroadenoma.

3. Treatment.

a. Bromocriptine (risk factor B) or Cabergoline (risk factor B) may be taken throughout pregnancy if the tumor enlarges. (Caution is advised in breast-feeding.)

b. If vision is threatened, surgical treatment is appropriate.

4. Sheehan’s syndrome is pituitary infarction, frequently associated with tumor, placental abruption, or other causes of hemorrhagic shock.

a. Manifests as inability to lactate, hypopituitarism, and hypothyroidism

b. Treatment involves steroid and thyroid replacement.

5. Lymphocytic hypophysitis mimics pituitary adenoma and suprasellar masses because it manifests as endocrinologic abnormalities, headaches, and a suprasellar mass at imaging. Lymphocytic hypophysitis occurs in pregnant and postpartum women. Biopsy is often needed to make the diagnosis. Steroid treatment with dexamethasone (category C) is often helpful.

PSEUDOTUMOR CEREBRI

Pseudotumor cerebri (idiopathic intracranial hypertension) is characterized by increased ICP not caused by an intracranial space-occupying lesion demonstrated at MRI or CT. Pregnancy does not cause pseudotumor cerebri. However, this disorder can occur in association with pregnancy. Pregnancy does not by itself cause visual loss. Pseudotumor cerebri does not cause miscarriage.

A. Symptoms and signs. Headache is the most common symptom (>90% of cases). Patients are otherwise alert and healthy. There are visual symptoms (transient visual obscurations) and auditory symptoms (whooshing noises). Signs include papilledema in almost all cases, and cranial nerve VI palsy. Most women are obese.

B. Differential diagnosis of papilledema and no mass lesion in pregnancy.

1. Cerebral venous thrombosis (most important; most frequently needs to be excluded)

2. Venous hypertension

3. Meningitis

4. Syphilis

C. Evaluation must include an imaging procedure (MRI and MR venography), cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) with opening pressure, and CSF constituents. Because the greatest threat to the patient is visual loss, visual acuity and visual field examinations must be performed frequently.

D. Treatment options.

1. Medical treatment.

a. Weight loss (restriction of weight gain is better than substantial weight loss)

b. Frequent lumbar punctures (LPs)

(1) Safe

(2) Painful, often difficult

c. Acetazolamide (500 to 2,000 mg) (risk C); can be continued in pregnancy; compatible with breast-feeding

d. Furosemide (Lasix; Aventis, Bridgewater, NJ, USA) (risk C)

e. Chlorthalidone (risk B); compatible with breast-feeding

2. Surgical treatment.

a. Optic nerve sheath decompression is the preferred procedure to save vision.

b. Lumbar and ventriculo-peritoneal shunts can be difficult for pregnant patients because of displacement/compression from the enlarging uterus.

CEREBROVASCULAR DISEASE

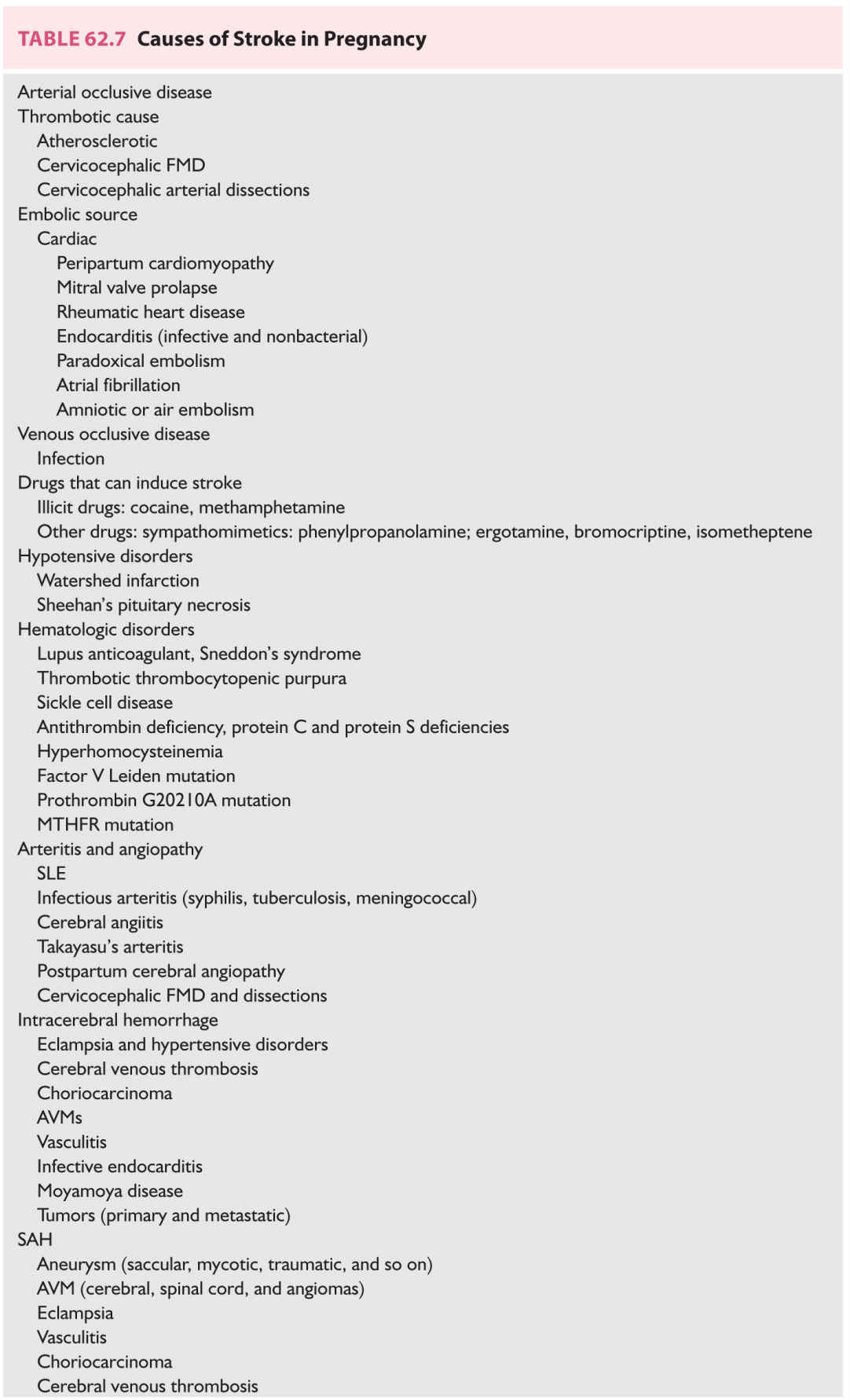

A. Attributable risk of ischemic stroke or intracerebral hemorrhage in pregnancy or the puerperium is 8.1/100,000 pregnancies. The causes of stroke during pregnancy are listed in Table 62.7.

1. Arterial stroke manifests as paresis but without altered consciousness or seizures; represents 90% of strokes during pregnancy.

2. Venous stroke manifests as headache, seizures, increased ICP, and alteration of consciousness; represents 80% of strokes during puerperium.

3. Intracranial hemorrhage characteristically manifests as sudden onset of headache, loss of consciousness, and accompanying neck stiffness and altered blood pressure.

4. Diagnosis.

a. CT and MRI (newer techniques of diffusion and perfusion may show early injury). Diffusion-weighted MR imaging and CT perfusion is very helpful.

b. Angiography occasionally required (including CT angio, MR angio)

c. Cardiac evaluation (transesophageal echocardiography—look also for right to left shunt)

d. Appropriate laboratory studies. The factor V Leiden mutation is now thought to be associated with at least one half of all cases of venous thromboses among white women. Consider protein C or protein S deficiency (may be falsely depressed simply because of pregnancy), antithrombin, antiphospholipid antibodies, platelets, fibrinogen, and homocysteine levels. Vasculitic screen: ANA, ENA, ANCA. Toxicology screen if indicated

5. Treatment is directed at the underlying cause; treatment should be individualized.

a. Heparin, unfractionated or low molecular weight, does not cross the placenta and can therefore be used safely during pregnancy. Low-molecular-weight heparin (risk category B) has been used. Safe for breast-feeding.

b. Warfarin (risk category D; X in first trimester; compatible with breast-feeding) crosses the placenta and is contraindicated during pregnancy because of the embryopathy associated with use. Can be used for breast-feeding.

c. Low-dose aspirin (81 mg/day) (risk category C) can be used safely in pregnancy when clinically indicated. Higher-dose aspirin is avoided. Other antithrombotic agents could be considered: Clopidogrel (risk category B) is an alternative to aspirin.

d. Management of acute ischemic stroke with tissue plasminogen activator [e.g., Alteplase (FDA C)]; is not currently recommended although there are isolated case reports of benefit.

e. Manage elevation of homocysteine levels with folate.

B. Cerebral venous thrombosis.

1. Occurs primarily postpartum. The signs and symptoms include headache, seizures, hemiplegia, papilledema, and fluctuating obtundation and/or coma, especially in internal cerebral vein thrombosis.

2. Diagnosis optimally with MRI and MR/CT venography; angiography, or venography is occasionally needed.

3. Treatment.

a. Correction of predisposing factors (infection and dehydration)

b. Control of seizures

c. Use of antiedema agents when appropriate

d. Anticoagulation (see Sections A.5.a. to c under Cerebrovascular Disease)

4. Risk factors for cerebral venous thrombosis include cesarean delivery, hypertension, infection other than pneumonia or influenza, drug abuse, especially cocaine, methamphetamines, and IV drug abuse.

C. Postpartum cerebral angiopathy (also known as RCVS) is a rare cause of a stroke-like syndrome characterized by seizure and focal neurologic deficits. Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction is found at angiography. Medications such as ergot alkaloids (e.g., ergonovine, bromocriptine, and ergotamine) and certain vasoconstrictive agents (isometheptene and sympathomimetic drugs) have been reported to cause the disorder. Treatment has been mainly supportive.

D. Hematologic disorders often manifest more frequently in pregnancy.

1. Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome is associated with recurrent pregnancy loss, fetal growth restriction, and severe preeclampsia and eclampsia.

2. Sickle cell disease

3. Deficiencies of antithrombin, or protein C or S

4. Thrombophilia, especially factor V Leiden mutation

E. Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). Table 62.8 causes include:

1. Intracranial aneurysm.

a. Thought to be present in 1% of all women of reproductive age; more likely in older, parous women

b. A significant contributor to maternal mortality

c. Rupture probably equally likely throughout pregnancy

d. Diagnosis requires CT and LP to look for RBCs, and angiography.

e. Optimum outcomes with surgical correction

f. Avoid nitroprusside because of its cyanide effect on the fetus. Hypertension can be controlled with verapamil or nimodipine.

g. Vaginal delivery should be anticipated after successful clipping unless obstetric contraindications exist. If delivery occurs before clipping, cesarean section or forceps delivery with epidural anesthesia is indicated.

h. Vasospasm can be managed with nimodipine (FDA C). Volume expansion must be monitored, because pregnant women are relatively more prone to pulmonary edema (decreased osmotic pressure).

i. Outcome.

(1) Grades 1 through 3: with expedited surgery, 95% successful outcome expected

(2) Grade 4: 45% to 75% mortality

(3) Fetal outcome: 27% mortality rate without surgery.

j. Subsequent pregnancies after successful clipping have a good prognosis.

k. Asymptomatic intracranial aneurysm should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis. When possible, these can be watched and treated after delivery ![]() (Video 62.2).

(Video 62.2).

2. Arteriovenous malformation (AVM)

a. Characteristically occurs in younger women who have had fewer pregnancies.

b. Diagnosis requires CT, LP, and angiography.

c. The malformation should be corrected, if possible, surgically or with embolic therapy.

d. Stereotactic radiation is not usually recommended during pregnancy.

e. Delivery is vaginal with epidural anesthesia and low-outlet forceps.

F. Eclampsia, severe preeclampsia.

1. Definition.

a. Preeclampsia (new-onset hypertension and proteinuria beyond 20 weeks gestation) complicates 5% to 7% of pregnancies.

b. Severe preeclampsia. One or more of the following is present: persistent blood pressures ≥160 mm Hg systolic and/or ≥110 mm Hg diastolic, 5 g proteinuria in 24 hours, oliguria (500 mL per 24 hours), elevated results of liver function tests, thrombocytopenia, persistent visual disturbances or headache, epigastric pain, pulmonary edema, or fetal growth restriction not explainable by other causes.

c. Eclampsia. Seizures or coma in a woman with preeclampsia in whom no other explanation can be found.

d. HELLP syndrome. A form of severe preeclampsia characterized by hemolysis, elevated results of liver function tests, and low platelet counts.

2. Symptoms and physical findings.

a. Headache, dizziness, scotomata, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain

b. Generalized edema

c. Funduscopic findings: segmental vasospasm, serous retinal detachment

d. Neurologic finding: hyperreflexia; cortical blindness

e. Bedside testing: visual acuity, Amsler grid for detection of scotomata

3. CT and MRI findings.

a. CT. Edema and hypodense lesions 75%, hemorrhage 9%

b. MRI.

(1) Severe preeclampsia. Deep white-matter signals on T2-weighted images

(2) Eclampsia. Signals on T2-weighted images at gray matter–white matter junctions, particularly in the parietal–occipital areas; cortical edema, hemorrhage; images look similar to hypertensive encephalopathy or posterior reversible encephalopathy.

4. Treatment.

a. Delivery remains on the only definitive treatment and should be accomplished at such time as either the mother is better off not being pregnant anymore or when a baby can be expected to do as well, or better, in the nursery than in utero.

b. Magnesium sulfate (FDA B; compatible with breast-feeding) is superior to IV diazepam and phenytoin in randomized controlled trials.

(1) Administered in a 4 to 6 g loading dose followed by 2 g/hour intravenously.

(2) Side effects include weakness, diplopia, ptosis, blurred vision, nausea, vomiting, and respiratory depression. Use with caution in the care of patients with reduced renal clearance or neuromuscular diseases such as myasthenia gravis (MG).

(3) Neurologic findings of magnesium toxicity include diminished muscle stretch reflexes, ptosis and diminished accommodation, nausea, flushing, and respiratory depression.

c. Blood pressure needs to be controlled to minimize risk of maternal vascular accidents (usually below 160 mm Hg systolic and 110 mm Hg diastolic) but kept high enough to adequately perfuse mother and fetus. The latter can be functionally assessed by maternal urine output and fetal heart rate monitoring.

d. Control seizures with an AED such as diphenylhydantoin (fosphenytoin) only if MgSO4 is unsuccessful.

e. Manage cerebral edema or herniation with hyperventilation, steroids, or mannitol after delivery.

5. Postpartum eclampsia (one-third of eclamptic convulsions do not begin until after delivery, usually within 24 to 48 hours after delivery), usually defined as within 7 days of delivery. Late postpartum eclampsia can occur up to 10 to 14 days after delivery. Consider the possibility of stroke, venous thrombosis, or reversible angiopathy whenever the diagnosis of late postpartum eclampsia is being considered.

6. Outcome.

a. The maternal mortality rate in the United States is 1% to 2%.

b. The perinatal mortality rate is 13% to 30%.

7. Complications.

a. Intracranial hemorrhage, frequently from uncontrolled hypertension

b. Congestive heart failure, frequently from iatrogenic fluid overload

c. Intrahepatic hemorrhage

MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS

A. Multiple sclerosis (MS) does not affect pregnancy per se, or vice versa. Although recent studies do show that there may be increased relapses postpartum, especially in the first 6 months postpartum (particularly in the relapsing–remitting form), pregnancy does not affect the rate of disability.

1. Patients who have sphincter disturbances or paraplegia may experience increased difficulty during pregnancy.

2. There is no evidence of vertical transmission of MS.

3. MS does not occur more frequently in pregnancy.

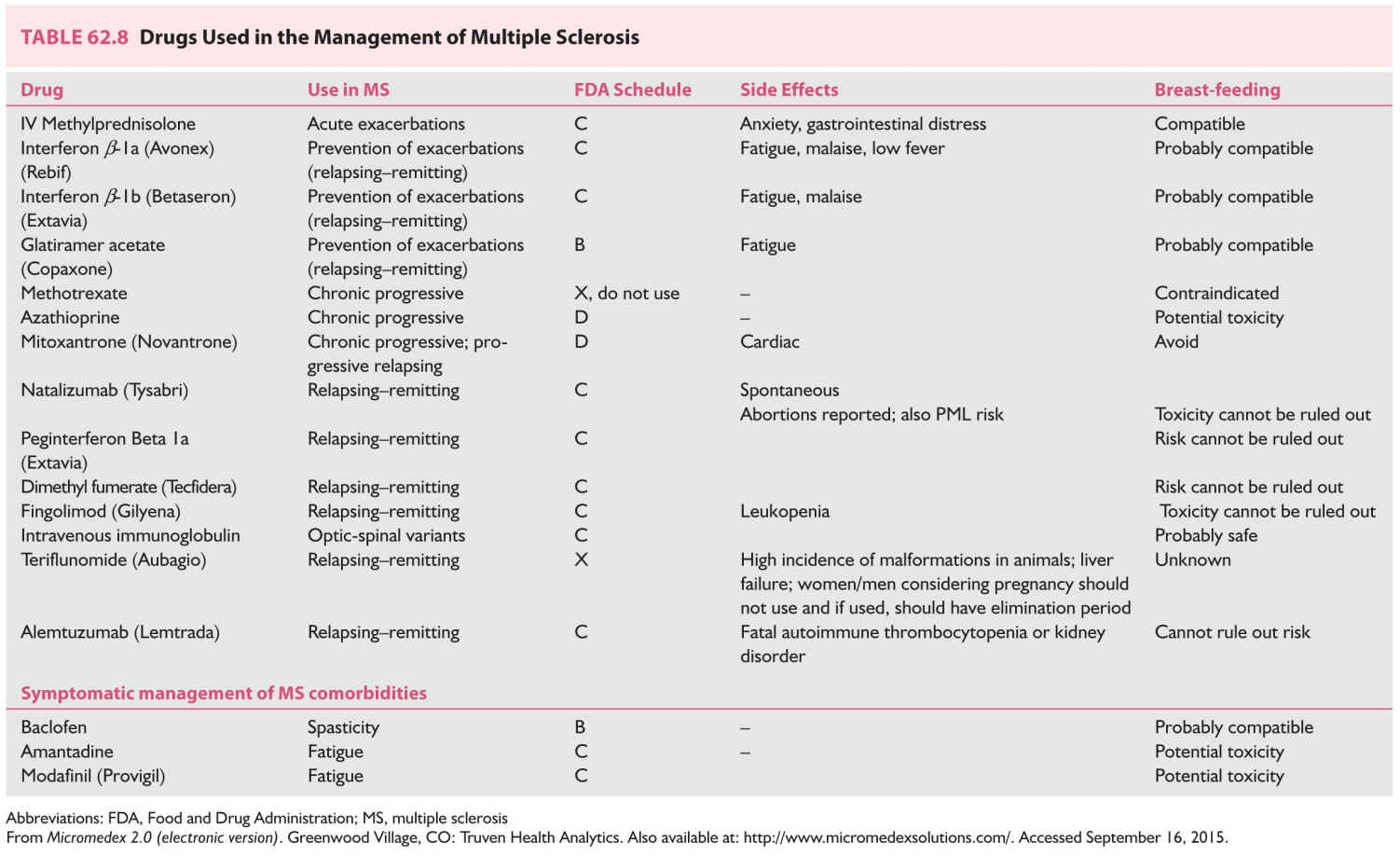

B. Management of acute MS in pregnancy (Table 62.8).

1. Semi-synthetic corticosteroids, most commonly methylprednisolone, are the mainstay for treatment of acute MS exacerbations during pregnancy (see Chapter 44).

2. The interferons and copolymer are not yet recommended in pregnancy, although patients who were pregnant have used the medications without fetal harm.

3. Avoid teriflunomide because it is currently labeled as an FDA Category X medication.

ROOT LESIONS AND PERIPHERAL NEUROPATHY

A. Lumbar disk.

1. Signs and symptoms are the same as in nonpregnant patients.

2. Generally treated nonoperatively. Consider surgery if there are bilateral symptoms or disturbances of sphincter function. Surgery during pregnancy is frequently associated with increased blood loss because of increased collateral flow.

B. Carpal tunnel syndrome.

1. Often exacerbated during pregnancy because of increase in extracellular fluid.

2. Pain and paresthesia are commonly worse at night and tend to be worse in the dominant hand.

3. Symptoms usually respond to nocturnal wrist splinting and resolve within 3 months postpartum.

1. Facial paresis of lower-motor neuron type when no other specific etiologic agent can be found. Signs and symptoms include abrupt onset, often with pain around the ear; feeling of facial stiffness and pulling to one side; difficulty closing the eye on the affected side; taste disturbances; and hyperacusis.

2. Approximately three times more likely to occur during pregnancy, primarily in the third trimester or immediately postpartum

3. Steroids are probably effective if given within the first 5 to 7 days (prednisone 1 mg/kg daily for 5 to 7 days). Surgery is ineffective.

D. Other forms of cranial nerve palsy.

1. Cranial nerve IV: reported rarely to occur; mechanism similar to cranial nerve VII or VI palsy

2. Cranial nerve VI: similar to above; usually resolve postpartum

E. Meralgia paresthetica.

1. Causes numbness in the lateral aspect of the thigh

2. Usually resolves within 3 months postpartum

F. Sciatica and back pain. Lumbosacral disk surgery should be reserved only for progressive atrophy or bowel or bladder dysfunction.

G. Guillain–Barré syndrome.

1. Causes are not generally affected by pregnancy.

2. Labor and delivery are otherwise normal.

MYASTHENIA GRAVIS

A. Variable weakness and fatigability of skeletal muscles resulting from defective neuromuscular transmission (reduced acetylcholine receptors in the neuromuscular junction)

B. Certain drugs should be avoided, including the following:

1. Ester anesthetics. tetracaine (Pontocaine; Sanofi Winthrop, New York, NY, USA) and chloroprocaine (Nesacaine; AstraZeneca, Wilmington, DE, USA)

2. Curare (and other nondepolarizing muscle relaxants)

3. Halothane (Fluothane; Wyeth-Ayerst, Philadelphia, PA, USA)

4. Aminoglycoside antibiotics

5. Quinine and quinidine

6. Magnesium sulfate. The antidote with MG is edrophonium (Tensilon; ICN, Costa Mesa, CA, USA), not calcium.

C. Treatment.

1. Antepartum.

a. Pregnancy per se does not affect the severity of preexisting disease.

b. Perinatal mortality is increased because of increased risk of premature delivery as well as neonatal MG.

c. Pharmacologic management of MG is not altered by pregnancy.

2. Intrapartum.

a. Oral medications should be discontinued at the onset of labor and the intramuscular equivalents continued until oral medications can again be ingested. Equipotent dosages are as follows:

(1) Neostigmine 0.5 mg intravenously

(2) Neostigmine 0.7 to 1.5 mg intramuscularly

(3) Neostigmine 15 mg by mouth

(4) Pyridostigmine 60 mg by mouth

b. Analgesia and anesthesia for labor require the utmost caution because of the risks of respiratory depression and aspiration.

c. Except for voluntary expulsive efforts in the second stage of labor, MG does not affect the progress of labor and is not an indication for cesarean section.

3. Postpartum.

a. Exacerbations are more likely to occur postpartum; tend to be sudden and severe in onset.

b. Women with severe disease or whose babies have symptoms after nursing should not breast-feed.

c. Most women return to preconceptional oral dosage with modest increases in dose to allow for the additional stresses of early parenthood.

D. Neonatal myasthenia.

1. Occurs in 10% to 15% of cases

2. Results from transplacental transfer of maternal antibody against acetylcholine receptors.

MYOTONIC DYSTROPHY

A. Clinical characteristics.

1. Autosomal dominant; weakness and wasting in muscles of face, neck, and distal limbs; myotonia of hands and tongue

2. Variable age at onset. The condition sometimes is diagnosed in mothers only after an affected child is born (these pregnancies are frequently complicated by polyhydramnios that results from poor fetal swallowing).

3. Predisposition to cardiac arrhythmias

4. Treatment. There is none for the dystrophy. Severe myotonia: phenytoin (FDA C), quinine (FDA D), and procainamide (FDA D).

B. Effects on pregnancy.

1. Increased risk of spontaneous abortion

2. Increased risk of premature labor and polyhydramnios, particularly with fetal involvement

3. Normal first stage of labor

4. Normal response to oxytocin

5. Prolonged second stage of labor

C. Labor management includes outlet forceps, regional anesthesia; avoid succinylcholine (can cause hyperthermia); nonpolarizing agents are generally safe.

MOVEMENT DISORDERS

A. Restless legs, the most common movement disorder in pregnancy. Most cases respond to massage, flexion/extension leg exercises, and walking. Treat with iron or folate if any suggestion of concurrent deficiency.

B. Chorea Gravidarum.

1. Most commonly due to medications, toxins, or infections

2. May be the initial manifestation of another disorder (e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus, Sydenham’s chorea)

3. Can be treated with low-dose haloperidol (FDA C)

C. Parkinson’s disease in pregnancy is rare because the age at which most patients have the disease is past childbearing years. However, pregnancy has been successfully accomplished in patients with Parkinson’s disease.

1. Pregnancy may adversely affect Parkinson’s in that there may be exacerbations soon after pregnancy.

2. Drugs used in Parkinson’s disease.

a. Levodopa (FDA C), MAO-B (selegiline, rasagiline—FDA C), dopamine agonists (pramipexole, ropinirole FDA C), and COMT inhibitor (entacapone FDA C).

b. Amantadine (FDA C) can increase the risk of complications and malformations.

Key Points

• Neurologic disorders are not rare in pregnancy, and all women seen, who are of childbearing age, should be considered to have a prepregnancy visit.

• Optimum control of the neurologic problem before pregnancy is ideal.

• The best outcome for the infant is optimal care of the woman in pregnancy.

• Use testing, including imaging, to determine the correct diagnosis.

• Use medications when necessary, keeping in mind the FDA drug classification.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree