10 Neurotic and other stress-related disorders

Concept of neurosis

Mental illness, which implies previous health, has been divided into psychoses and neuroses.

Aetiology

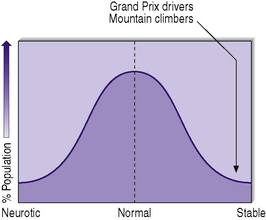

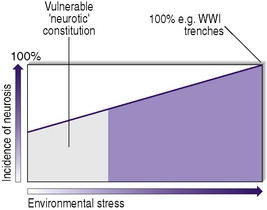

The vulnerability of the general population to developing a neurosis under stress follows a normal distribution, as for height or weight (Figure. 10.1). The incidence of neurosis rises with increasing environmental stress (Figure. 10.2). Even normal stable personalities will develop neurosis under severe environmental stress, as can be seen in individuals involved in natural disasters and in war time. During the First World War, the incidence of neurosis approached 100% in individuals in the trenches for prolonged periods, and this was similar in bomber crews during the Second World War after more than 30 missions. Although one person’s stress may be another’s pleasure (owing to the individual’s background and personality), certain situations such as combat are experienced as stressful by over 95% of individuals. Lower percentages experience stress in examinations or public speaking, and up to 50% of the population find job interviews stressful. Although not associated with external stresses, sensory deprivation (either experimentally or as experienced by hostages kept in solitary confinement) and, to a lesser extent, boredom can also result in extreme stress and anxiety.

As stated above, stress factors can be precipitating factors for neuroses in vulnerable individuals, and environmental factors, including family and marital factors, and social conditions such as poor housing and unemployment, may be perpetuating factors for such disorders. Table 10.1 summarizes factors associated with the development of neurotic and stress-related disorders.

Table 10.1 Factors associated with development of neurotic and stress-related disorders

| Lower social class |

| Unemployment |

| Divorced, separated or widowed |

| Renting rather than owning own home |

| No educational qualifications |

| Urban rather than rural |

The homeless and prisoners have twice the risk of general population.

Prognosis

Classification

ICD-10 has not retained the concept of a neurosis as a major organizing principle in classification, although it groups three types of disorder together because of their historical association with the concept of neurosis, and also their association with psychological causation. These are the neurotic and stress-related disorders (which are considered in this chapter) and the somatoform and dissociative disorders, which are described in Chapter 11. Table 10.2 summarizes neurotic and stress-related disorders on the basis of ICD-10. Mixed neurotic states are more common than the discrete syndromes. Panic disorder with or without agoraphobia and generalized anxiety disorder are the most disabling. Table 10.3 shows the frequency of neurotic conditions. DSM-IV-TR uses the term ‘anxiety disorders’ rather than ‘neurotic disorders’ and, indeed, neurosis was absent from DSM-III. Table 10.4 compares DSM-IV-TR with ICD-10 in relation to neurotic and stress-related disorders.

Table 10.2 Neurotic and stress-related disorders based on ICD-10

| Disorders | Features |

|---|---|

| Generalized anxiety disorder | Generalized and persistent ‘free floating’ anxiety symptoms involving elements of: • apprehension (worries about future misfortunes, ‘feeling on edge’, difficulty in concentrating, etc.) |

| Mixed anxiety and depressive disorder | Symptoms of anxiety and depression are both present but neither clearly predominates |

| Panic disorder | Recurrent attacks of severe anxiety (panic) not restricted to any particular situation or set of circumstances, and therefore unpredictable |

| Secondary fears of dying, losing control or going mad | |

| Attacks usually last for minutes only and patients often experience a crescendo of fear and autonomic symptoms | |

| Comparative freedom from anxiety symptoms between attacks, although anticipatory anxiety is common | |

| Phobic disorders | Anxiety is evoked only, or predominantly, by certain well-defined situations or objects external to the subject, which are not currently dangerous, and these are characteristically avoided or endured with dread |

| Specific (isolated) phobias | Restricted to highly specific situations such as proximity to particular animals, heights, thunder, flying, blood, etc. |

| Agoraphobia | Fear not only of open spaces but also of related aspects, such as the presence of crowds and difficulty of immediate easy escape back to a safe place, usually home |

| May occur with or without panic disorder | |

| Social phobias | Fear of scrutiny by other people in comparatively small groups (as opposed to crowds), leading to avoidance of social situations |

| Obsessive–compulsive disorder | Recurrent obsessional thoughts or compulsive acts |

| At least one thought or act still unsuccessfully resisted | |

| Thought of carrying out the act is not pleasurable | |

| Thoughts, images or impulses must be unpleasantly repetitive | |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | Delayed and/or prolonged response to stressful event or situation of threatening or catastrophic nature, likely to cause distress in anyone |

| Episodes of repeated reliving of the trauma in intrusive memories (‘flashbacks’), dreams or nightmares | |

| Sense of ‘numbness’ and detachment from other people | |

| Avoidance of activities and situations reminiscent of trauma | |

| Usually autonomic hyperarousal with hypervigilance, an enhanced startle reaction and insomnia |

Table 10.3 Relative frequencies of neurotic conditions

| Condition | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Mixed anxiety and depression | 48 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 28 |

| Depression | 14 |

| Phobia | 12 |

| Obsessive–compulsive disorder | 10 |

| Panic disorder | 6 |

Table 10.4 Comparison of ICD-10 and DSM-IV-TR neurotic/anxiety disorders

| ICD-10 | DSM-IV-TR |

|---|---|

| F40: Phobic anxiety disorders | |

| F40.00 Agoraphobia without panic disorder | 300.22 Agoraphobia without history of panic disorder |

| F40.01 Agoraphobia with panic disorder | 300.21 Panic disorder with agoraphobia |

| F40.1 Social phobias | 300.23 Social phobia |

| F40.2 Specific (isolated) phobias | 300.29 Specific phobia |

| F41: Other anxiety disorders | |

| F41.0 Panic disorder (episodic paroxysmal anxiety) | 300.01 Panic disorder without agoraphobia |

| F41.1 Generalized anxiety disorder | 300.02 Generalized anxiety disorder |

| F41.2 Mixed anxiety and depressive disorder | 300.00 Anxiety disorder NOS |

| F42: Obsessive–compulsive disorder | 300.3 Obsessive–compulsive disorder |

| F43: Reaction to severe stress and adjustment disorders | |

| F43.0 Acute stress reaction | 308.3 Acute stress disorder |

| F43.1 Post-traumatic stress disorder | 309.81 Post-traumatic stress disorder |

| F43.2 Adjustment disorders | 309.9 Adjustment disorders |

Anxiety disorders

Normal anxiety

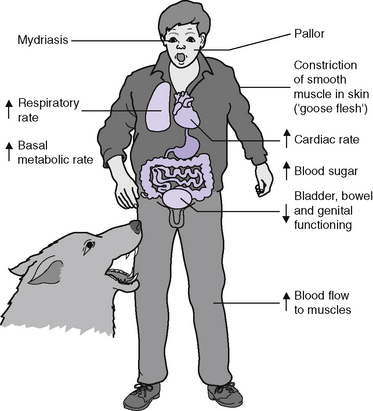

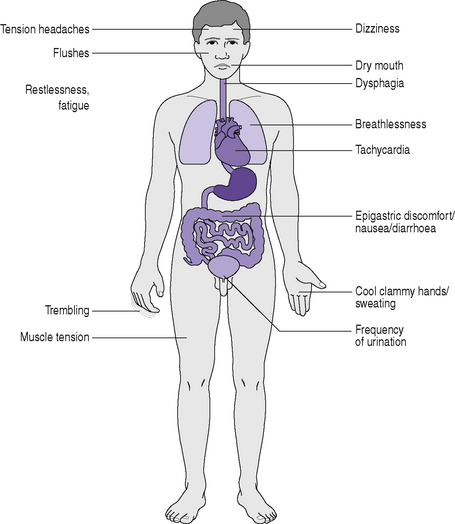

Anxiety is a mood, usually unpleasant in nature, accompanied by bodily (somatic) sensations and occurring with a subjective feeling of uncertainty and threat about the future. The term ‘fear’ is used to describe a normal and appropriate mood when the danger can be perceived and defined. Most of the bodily changes seen in anxiety are caused by increased sympathetic adrenergic nervous system discharges, i.e. Cannon’s fight or flight reaction (Figure. 10.3), which results in the release of adrenaline and other catecholamines. In our ancestral past such a reaction would prepare us to deal with a real physical threat, but today we may merely experience such reactions when under stress in everyday life, for instance in a traffic jam.

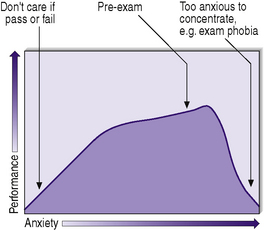

We all attempt to adjust our lives to maintain anxiety at an optimal level for us as individuals. However, like pain, anxiety is a useful warning and should not be suppressed with drugs or alcohol. It is the central nervous system’s alarm system to protect us from threat, and is activated by environmental cues. There is an inverted U-shaped relationship between anxiety and performance developed by Hebb in 1955 known as the Yerkes–Dodson law (Figure. 10.4). This was based on an experiment on white mice being encouraged by low-, medium- and high-intensity electric shocks to learn to locate a compartment in a box. Medium-intensity shocks produced the fastest learning. Performance is reduced at low and very high levels of anxiety: thus poor examination results are obtained by those with low anxiety levels who do not care whether they pass or fail, and by those who become so highly anxious that they cannot concentrate. The Yerkes–Dodson law predicts that anxiolytic drugs reduce performance in someone with a low anxiety level, but when a deterioration in performance is caused by high anxiety, the reduction of symptoms by anxiolytic drugs should improve performance, for example in examination phobia. In assessing an individual’s true level of anxiety, one should bear in mind that the complaint of symptoms of anxiety may lie anywhere along the Yerkes–Dodson curve. The individual may also be very anxious during a formal interview, but not so for long periods during the day, or vice versa. It is useful to distinguish between trait anxiety, which is a lifelong personality characteristic, and state anxiety, which is a temporal disorder with a discernible time of onset.

Generalized anxiety disorder

Clinical features

These are summarized in Figure 10.5 and Table 10.5. Individuals will not have all the psychic (affective) and somatic symptoms, but will tend to have the same symptoms during each exacerbation, for example palpitations or trembling.

Table 10.5 Psychological features of generalized anxiety disorder

| Symptoms | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Psychic | Feelings of threat and foreboding |

| Difficulty in concentrating or ‘mind going blank’ | |

| Distractible | |

| Feeling keyed up, on edge, tense or unable to relax | |

| Early insomnia and nightmares | |

| Irritability | |

| Noise intolerance (e.g. of children or music) | |

| Panic attacks | Unexpected severe acute exacerbations or psychic and somatic anxiety symptoms with intense fear or discomfort |

| Not triggered by situations | |

| Individuals cannot ‘sit out’ the attack | |

| Other features | Lability of mood |

| Depersonalization (dream-like sensation of unreality of self or part of self) | |

| Derealization (dream-like sensation of unreality of world) | |

| Hypnogogic and hypnopompic hallucinations (when, respectively, going off to or waking from sleep) | |

| Perceptual distortion (e.g. distortion of walls or the sound of other people talking) |

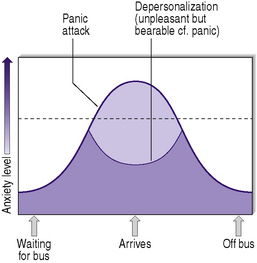

Depersonalization and derealization are sometimes associated with generalized anxiety disorder and are disorders of self-awareness. In depersonalization, an individual has an altered or lost sense of personal reality or identity. In derealization, an individual’s surroundings feel unreal. Individuals find these symptoms unpleasant and difficult to describe, and are relieved when they are acknowledged by professionals. Such feelings can occur in normal individuals, especially those suffering loss of sleep, as well as in a primary depersonalization–derealization syndrome. They are also seen in individuals suffering from depression, schizophrenia, alcohol and drug intoxication and withdrawal, and epilepsy. It may also be induced by prescribed medication. Although unpleasant, they are bearable compared to panic attacks, which are associated with higher levels of anxiety (Figure. 10.6).

Differential diagnosis

Many disorders and nearly all psychiatric conditions may present primarily with symptoms of anxiety (Table 10.6). Generalized anxiety disorder very rarely begins after age 35; individuals presenting for the first time after this age are more likely to be suffering from depressive or other psychiatric disorders, but the distinction between general anxiety disorder and depression can be difficult. Rotational vertigo is not a symptom of anxiety.

Table 10.6 Disorders that can present primarily with symptoms of anxiety

| Generalized anxiety disorder |

| Panic disorder |

| Phobic disorders |

| Obsessive–compulsive disorder |

| Depressive disorder |

| Schizophrenia and other paranoid psychoses |

| Drug and alcohol withdrawal syndromes (e.g. delirium tremens) |

| Early dementia (e.g. catastrophic reactions on psychometric testing) |

| Ictal anxiety due to epilepsy, especially temporal lobe epilepsy |

| Thyrotoxicosis |

| Phaeochromocytoma |

| Unexpressed complaints of physical illness (e.g. lump in breast) |

| Drug and alcohol abuse, dependency and withdrawal symptoms (e.g. delirium tremens, caffeinism) |

Aetiology

Biological models of general anxiety disorder have been hypothesized, and involve:

Management

Pregabilin, which has been used in neuropathic pain, has also more recently been found to be of use.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree