Fig. 1

Smallpox contagion in Mexico from Old World incomers, as illustrated in Bernardino de Sahagún, Historia general de las cosas de Nueva España (General History of the Things of New Spain, circa 1575–1580). The text says “… an epidemic broke out, a sickness of pustules. It began in Tepeilhuitl. Large bumps spread on people; some were entirely covered… The pustules that covered people caused great desolation; very many people died of them, and many just starved to death; starvation reigned, and no one took care of others any longer” [reproduced with permission from Lockhart (1993)]

Treponema pallidum was identified in 1905 as causative agent of syphilis by Fritz Schaudinn (1871–1906) and Erich Hoffmann (1868–1959). Following infection, neurosyphilis can appear as late-onset form typically 4–25 years later. The semeiology of spinal cord disease, tabes dorsalis, included, among other signs and symptoms, the characteristic Babinski sign, named after the neurologist Joseph Babinski (1857–1932). Working at Hôpital de la Pitié in Paris, Babinski described, in patients affected by tabes dorsalis, the sign named after him, which has become in neurology a cardinal sign of the pyramidal syndrome.

Another late-onset form of neurosyphilis was general paresis with dementia, which made many victims including several famous artists, philosophers and politicians. Interestingly, in 1917 malaria fever therapy became a treatment of choice of neurosyphilis after the description by Julius Wagner-Jauregg (1857–1940). To be awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1927, he had to wait the retirement of the psychiatry expert of the Nobel Committee, in whose view Wagner-Jauregg’s treatment based on injecting malaria was criminal (Whitrow 1990). The citation of the Prize (http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/1927/press.html) included the following:

How then did Wagner-Jauregg proceed to heal the unfortunate victims of this terrible disease? There is a saying «one must expel evil with evil» that might aptly have been coined as a motto for his treatment of paralysis. He healed the mental patients by infecting them with another disease—malaria.

Malaria fever treatment of general paresis was still described in detail in Lord Brain’s classical textbook “Diseases of the Nervous System” as late as 1962. The treatment was given by transmission of parasites from a patient with malaria to patients suffering from general paresis or by the bite of mosquitoes infected with the relatively benign Plasmodium vivax, which in England could be obtained through the Ministry of Health.

The peculiar wisdom to contract malaria before being exposed to the risk of syphilis was already well known by sailors. Syphilis is, thus, an example from the past of how a microbe can control the growth of another microbe. Neurosyphilis also highlights the potentials of microbes to cause severe neuropsychiatric disorders and dementia that appear with a very late onset after the initial infection. The mechanisms of these late-onset forms of the disease, however, have not been clarified because, with the advent of efficient prevention and antibiotic treatment, neurosyphilis is no longer a major public health problem, and lost its position as major neurological or neuropsychiatric disease.

2.2 Poliomyelitis

This disease is typical of the twentieth century (Fig. 2): sizable epidemics appeared at the beginning of the century and were close to elimination at the end of the century. Before Karl Landsteiner (1868–1943) discovered in 1909, in cooperation with Erwin Popper (1879–1955), its causative pathogen, poliovirus, the paralytic aspects of the disease were considered to be its characteristic feature and the disease was denominated “infantile paralysis”.

Fig. 2

Patients with “infantile paralysis” during an epidemic of poliomyelitis that filled up the iron lung ward at Rancho Los Amigos Hospital in California (USA), circa 1953. Source: Food and Drug Administration, public domain

With the introduction of mass vaccinations, this severe, disabling, disease has almost completely disappeared. This illustrates that results obtained from experimental basic research, i.e. isolation of the virus in cell culture, can be translated into the elimination of a severe nervous system disorder. However, the elimination of polio left a number of interesting problems concerning its pathogenetic mechanisms unsolved (Nathanson 2008).

2.3 Lethargic Encephalitis

This disease is also called von Economo disease after Constantin von Economo (1876–1931; a disciple of Wagner-Jauregg), who presented his studies on this new nosological entity in 1929.

Lethargic encephalitis appeared in 1916 and disappeared as mysteriously as it had appeared 10 years later after sweeping three times around the world infecting millions of people and killing one-third of them. It caused severe sleep disturbances: most patients were lethargic, others were insomniac, and some developed narcolepsy-like sleep episodes. Survivors could, with a late onset, develop severe behavioral disturbances, or a Parkinson-like disorder, or both.

Neuropathological studies of victims of lethargic encephalitis heralded the localization of sleep-wakefulness regulating areas in the brain (Triarhou 2006; Bentivoglio and Kristensson 2007). The pathogen was never isolated, but the disease highlights that we should remember that infectious diseases causing severe mental disturbances and neurodegenerative disorders can suddenly become a real threat and be spread rapidly over the world.

3 Present

With discoveries and progress of vaccines and antibiotic therapy, the infectious diseases of the nervous system have, during the past 50–60 years, fallen more or less out of favor in the neurological community, and are currently handled mostly by health authorities and infectious disease clinics. Since the early 1970s, the rapidly growing field of neuroscience has focused on other important areas of clinical and basic research. Thus, with the exception of HIV infection, infectious diseases of the nervous system have become a relatively neglected area of research.

As mentioned previously, the NTD do not include “the big three” infections (malaria, tuberculosis, HIV-AIDS). It is, however, frequently forgotten that important sequels may follow or may appear as late-onset disorders caused by cerebral malaria and HIV infections in infancy, namely epilepsy and cognitive disturbances (Newton and Wagner 2014; Kihara et al. 2014). These also represent an area of investigation up till now neglected in neuroscience. Importantly, the occurrence of seizures increases misunderstandings, stigmatization, social isolation caused by NTD, though epilepsy can be often managed by treatment with anti-epileptic drugs (Scorza et al. 2013).

Infections with worms affect annually hundreds of millions of people worldwide and some are often accompanied by complications of the central nervous system (CNS), e.g. cysticercosis (Fig. 3), causing neurocysticercosis (Carpio 2014). Others spread more rarely to the CNS, e.g. schistosomiasis (Fig. 4) (Ferrari 2014), onchocerciasis (Njamnshi and Zoung-Kanyi Bissek 2014) and other nematode infections (Intapan et al. 2014). As these infections are very common and causative pathogens are widely spread, the CNS is under a constant threat for millions of people. For example, over 230 million people are estimated to require treatment for schistosomiasis yearly (WHO 2012), and the blood flukes of the genus Schistosoma can cause neuroschistosomiasis in a proportion of cases (Ferrari 2014).

Fig. 3

Countries and areas at risk of cysticercosis in 2009 (reproduced by the permission from WHO)

Fig. 4

WHO map on prevalence of schistosomiasis in 2011 (reproduced by the permission from WHO)

Among protozoa targeting the nervous system, infections with Toxoplasma gondii are common in high-income countries and are not included in the NTD group, while infections by Trypanosoma (T.) brucei in Africa and T. cruzi in Latin America represent severe NTD.

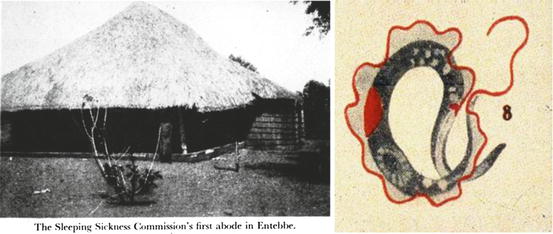

T. brucei, the causative agent of human African trypanosomiasis or sleeping sickness, is an example of a parasite that has predilection for the brain (Buguet et al. 2014; Masocha et al. 2014). This parasite caused large epidemics in sub-Saharan Africa at the turn of the twentieth century (Fig. 5). Two-thirds of the population in Uganda died during the 1896–1906 epidemic. African trypanosomiasis, which also causes infections of livestock (nagana), probably severely impeded the pre-colonial social and economic development of sub-Saharan Africa. With surveillance and better control of the T. brucei vector, the tsetse fly, the prevalence of human African trypanosomiasis rapidly declined in the second part of the twentieth century. However, the disease then re-emerged as control measures were neglected due to political unrest and civil wars, and was reported to affect >300,000 persons in 1998. Continued control measures have now brought the number of reported cases down to below 10,000 (WHO 2013), although this is probably an underestimate.

Chagas disease is the human infection caused by T. cruzi (Coura 2014). The infection, which affects primarily rural populations, has serious consequences for public health in Latin America, where it is estimated to have killed 10,000 people in 2008 (WHO 2012). It is an infection probably as old as mankind, as T. cruzi DNA was found in mummified bodies of 9,000 years ago. Carlos Chagas (1879–1933) in Brazil, in 1909, not only described the disease but also discovered the new Trypanosoma species he would prove to be the pathogen, and identified an insect vector, the triatomines (Fig. 6). Charles Darwin (1809–1899) is described to have been attacked by a triatomine bug during his expedition in 1835, and developed much later symptoms compatible with Chagas disease (Adler 1997). Triatomines are called “kissing bugs” because they bite near the lips and the eyes (the so-called kiss of death).

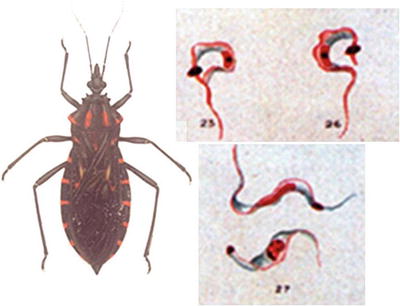

Fig. 6

Drawings from the first description, by Carlos Chagas of the vector (the triatomine bug Panstrongylus megistus is here depicted) and causative parasite, Trypanosoma cruzi, of Chagas disease or American trypanosomiasis [reproduced from Chagas (1909); kindly provided by JR Coura]

About 30 % of chronically infected people develop after a very long clinical latency the cardiac and/or gastrointestinal forms of Chagas disease, with progressive denervation of viscera which makes of this disease a major disorder of the autonomic nervous system. The pathogenesis of neurodegenerative events in Chagas disease is still enigmatic. Spread of T. cruzi to the brain, with reactivation of the acute form of Chagas disease, is of increasing concern in immunosuppressed individuals, including HIV-AIDS patients.

Leprosy can serve as an example of a NTD caused by bacteria. This chronic infection attacks the peripheral nervous system (Masaki and Rambukkana 2014), and is a severe social stigmatizing condition due to the accompanying conspicuous damages to the skin and extremities that are the result of sensory disturbances.

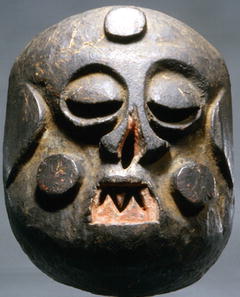

Disfigurement caused by leprosy has fired imagination in all cultures (Fig. 7). There are accounts of leprosy throughout recorded history, in ancient civilizations in Egypt (leprosy was probably described in an Egyptian papyrus written around 1550 B.C.), China, and India (where the earliest certain account of leprosy was reported between 600 and 400 B.C.). Leprosy may also represent a travel medicine disease, believed to have been brought from India to Greece by the soldiers of Alexander the Great in the fourth century B.C. (Sherman 2006). Segregation and even harsh punishment of lepers (up to burning them alive), the use of a leper clapper or bell to make them manifest and isolate lepers are well documented not only in Europe in the Middle Ages, but also elsewhere and throughout centuries. The renowned parable of the “healing-miracle” of Jesus encountering the ten lepers on the road to Galilee (Gospel of Luke 17:11–19) presented leprosy in the context of faith and salvation (Fig. 8).

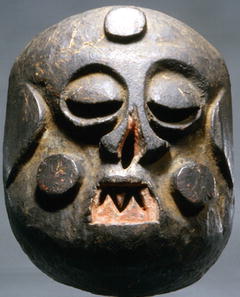

Fig. 7

Nigerian mask (idiok ehpo mask, Ibibio, Nigeria) representing the disfigurement caused by leprosy to indicate moral ugliness. Photo credit: Charles Davis (reproduced with permission)

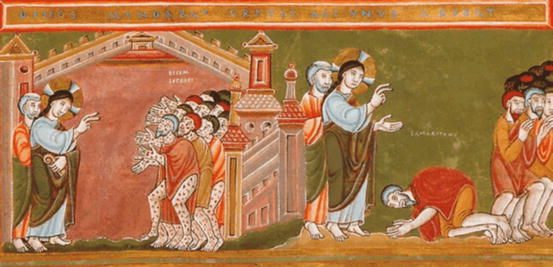

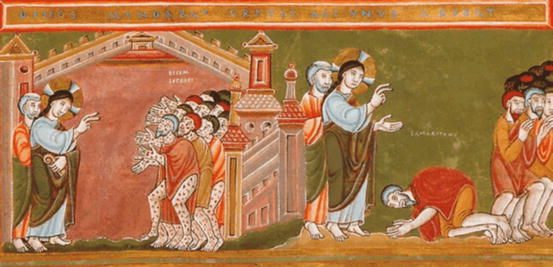

Fig. 8

Illustration of the Gospel parable “The Cleansing of the Ten Lepers”, or “The Grateful Samaritan” (in addition to the healing the Samaritan shares with the other nine lepers, he has become a believer in Jesus), from the “Codex Aureus” (the early medieval “Golden Code” that collected the Gospels) (available in the public domain)

Medical salvation of leprosy had, however, to wait for many centuries. The causative pathogen, Mycobacterium leprae, was discovered in 1873 by Gerhard Armauer Hansen (1841–1912) through his work in the Norwegian seaport Bergen. Hansen was sued and lost his post at the hospital when trying to prove his discovery by infecting a patient suffering from the anesthetic form of leprosy (Jay 2000). However, his efforts lead to a marked decline of the disease in Norway, and represented an obvious turning point in the fight against leprosy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree