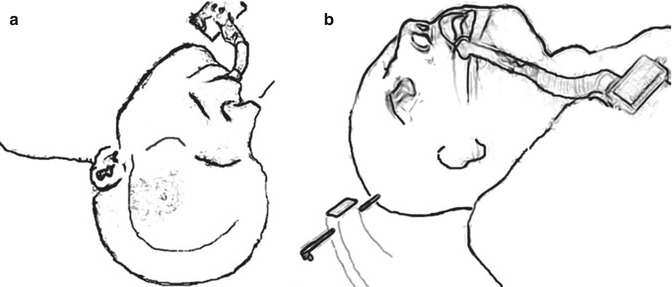

Fig. 13.1

Depiction of an extended pterional approach in which a larger frontal and temporal exposition is accomplished after craniotomy

The benign slow growth of these tumours means they frequently reach a large size before detection. Surgical removal of small- to midsized tumours is not difficult. Yet, in a significant proportion of patients the meningioma is very large and infiltrates or envelopes surrounding structures, making removal challenging due to strong attachment.

13.2 Preoperative Evaluation

As a rule, patients harbouring OGMs may present with headache, visual loss, seizure and mental or personality changes, occasionally complaining of spontaneous loss of sense of smell. A detailed neuro-ophthalmologic evaluation should be performed, and a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study with gadolinium enhancement is important for the diagnosis. Usually the tumour shows a dense contrast enhancement that pushes the frontal lobe upward and is associated with significant oedema. An MRI angiogram could be useful to see the position of the ethmoidal arteries. Preoperative embolisation is not indicated in the majority of cases in our opinion.

13.3 Surgical Anatomy

OGMs are located in the midline of the anterior fossa, over the cribriform plate of the ethmoid bone, close to the planum sphenoidale [8, 30]. The tumour may involve the area from the crista galli to the posterior planum sphenoidale and may be symmetric around the midline or extend predominantly to one side (Fig. 13.2).

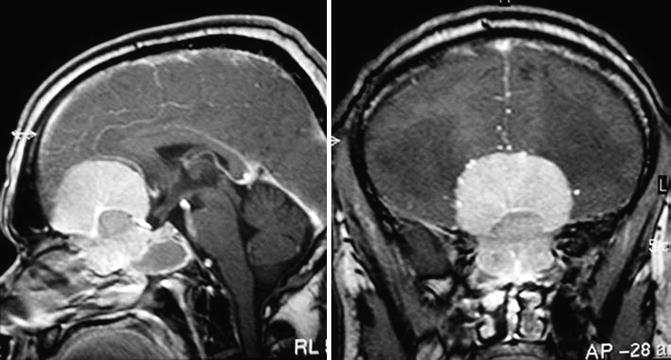

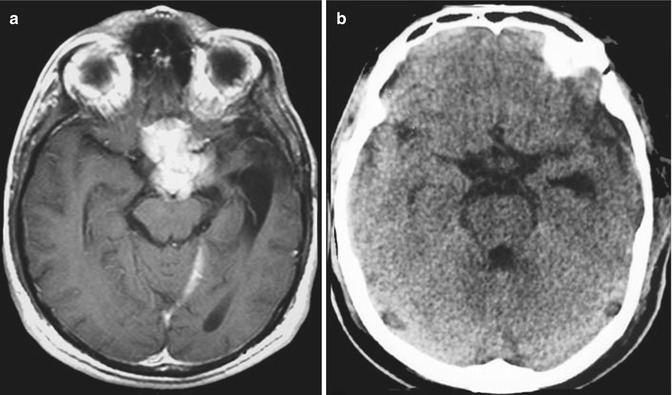

Fig. 13.2

An olfactory groove meningioma displacing posteriorly the pons (a), which was removed completely by a pterional approach (b)

The olfactory nerves are displaced laterally on the surface of smaller tumours and it may be possible to preserve at least one of these nerves. In large tumours, both olfactory nerves and cribriform area are destroyed and invaded by the tumour. Therefore, olfaction may not be salvageable. With large tumours, the optic nerves and chiasm are pushed inferiorly and posteriorly.

The primary blood supply comes from branches of the ophthalmic artery (anterior and posterior ethmoid artery) and branches of meningeal arteries, through the midline of the base of the skull. The tumour displaces posteriorly the A2 segments of the anterior cerebral arteries; however, they have a cleavage plane, where brain tissue and arachnoid are present between the two structures (Fig. 13.3). In large tumours, the capsule of the tumour may envelop the A2 segments of the anterior cerebral artery, making total removal a risky procedure. Frontopolar and other small branches of the anterior cerebral arteries may also be adhered to the posterior and superior tumour capsule.

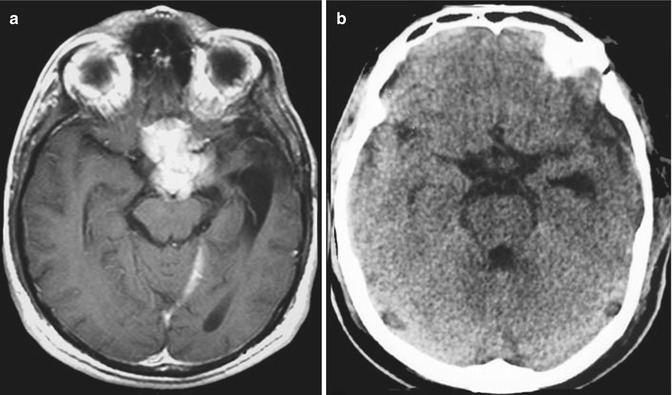

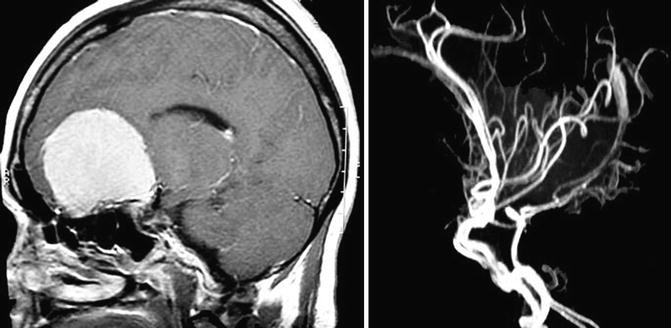

Fig. 13.3

A large olfactory groove meningioma displacing the anterior cerebral complex seen by magnetic resonance imaging (left) and magnetic resonance angiography (right)

13.4 Approaches

Many surgical approaches can be applied for tumour removal, although the traditional method is frontal or bifrontal craniotomy with subfrontal approach to the tumour [1, 5, 9, 11, 13, 18, 20, 23, 25, 28, 30, 31]. In some cases, part of the orbit may be removed to improve the frontobasal exposure (Fig. 13.4). The pterional approach has been advocated by many authors and, in our opinion, is the first choice for small- and midsized tumours [1, 6, 14, 21, 26, 32, 34]. Aggressive approaches have been used in OGMs that have expanded into the paranasal sinuses and orbits, including transbasal [7], subcranial [10, 24] and fronto-orbital approaches [27], frontal or bifrontal craniotomy being associated with orbital or nasal osteotomies [4, 15] and craniofacial resection [12].

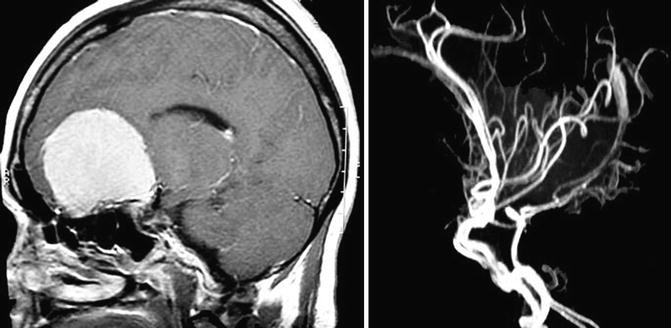

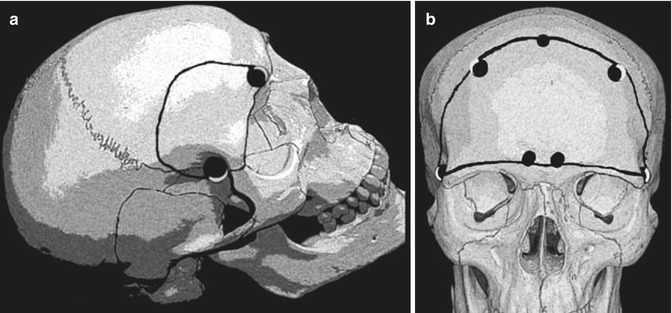

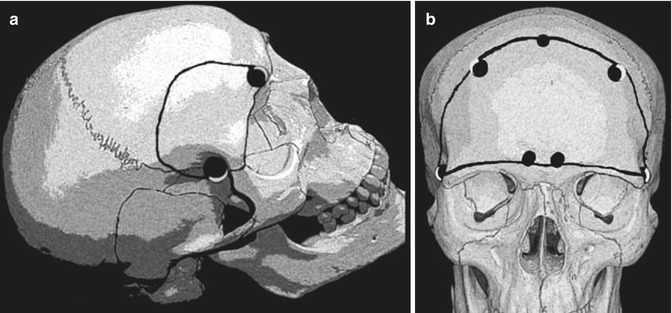

Fig. 13.4

Craniotomies used to remove olfactory groove meningiomas. The superior arch of the orbit may be removed (a) to accomplish a better frontobasal exposure. Some cases may need a bifrontal approach (b)

13.5 Frontotemporal Approach for Small and Midsized Tumours

The patient should be placed in the supine position with the head held in Mayfield three-point fixation or Sugita multiple-point fixation. The head is gently rotated 30° towards the contralateral shoulder. More rotation can be used for anterior tumours and less for more posterior tumours. The head is flexed slightly to bring the chin towards the ipsilateral clavicle and extended to bring the maxillary eminence to the highest point in the field (Fig. 13.5).

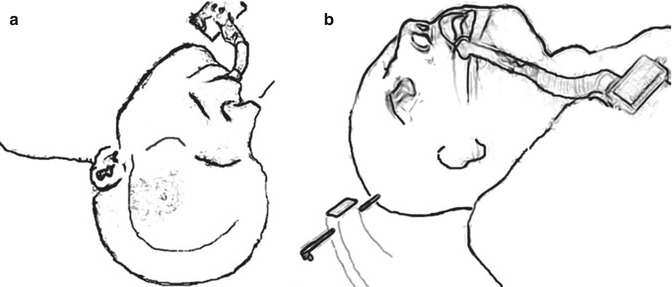

Fig. 13.5

Schematic depiction of head positioning: (a) frontal view, and (b) lateral view (see text for details)

A curvilinear skin incision is made behind the hairline. The incision begins just anterior to the tragus of the ear and should extend below the zygomatic root to protect the branches of the facial nerve. The incision should be made as close as possible to the tragus of the ear. We should avoid transecting the underlying branches of the superficial temporal artery. The skin flap is folded anteriorly along the pericranium. At the supraorbital ridge, care should be taken to identify and preserve the supraorbital nerve and vessel passing through the supraorbital foramen or notch. As the skin is folded anteriorly, the galea will merge with the superficial layer of the temporalis fascia. A curvilinear incision can be made into the superficial fascia layer at keyhole and continued towards the zygomatic root. Anterior elevation of this fascia and fat pad away from the underlying temporalis muscle avoids injury to the frontalis branch of the facial nerve that runs in this fat plane. The temporalis muscle is elevated as a separate layer and folded anteriorly and inferiorly using fish hooks to expose the supraorbital ridge lateral rim of the orbit.

The craniotomy is accomplished with four burr holes and by means of craniotome, where, as a rule, we use Midas Rex®, with a cut burr. Typically, the dura mater is opened in a C-shaped fashion with its base along the sphenoid ridge. It is folded anteriorly and anchored with stay sutures.

The Sylvian fissure is opened with the aid of an operating microscope, either a lateral-to-medial or a medial-to-lateral overture of the Sylvian fissure could be performed. In the lateral-to-medial dissection, the Sylvian fissure is then opened using an arachnoid knife, and the dissection is performed superior to the Sylvian vein, reflecting the veins with the temporal lobe. Veins crossing the fissure are sacrificed. As the fissure opens, the distal branches of the middle cerebral artery, the M1 bifurcation and finally the carotid bifurcation can be exposed. Further dissection allows visualisation of the carotid optic triangle and the carotid–oculomotor triangle. On a medial-to-lateral dissection of the Sylvian fissure, a self-retractor is placed under the frontal lobe to expose the olfactory nerve. Following the surface of the tumour to behind it posteriorly allows easy identification of the optic nerve and the carotid artery lying laterally to it. The optic carotid cistern and carotid oculomotor cistern generally come into view easily with little retraction. With the use of fine microdissectors, the arachnoid membrane between the optic nerve and frontal lobe is incised and opened. The dissection of this arachnoid continues across the carotid artery to the region of the third nerve, thus opening the optic carotid and carotid oculomotor cisterns. The microsurgical technique consists of dissecting the tumour capsule from the optic nerve in front of and behind the optic nerve in the side view of the surgeon. The frontal lobe is elevated with a retractor and the surface between the tumour and frontal lobe dissected.

Small feeds are also coagulated by means of bipolar forceps and the blood supply occluded along the base and the tumour capsule. The overture in the tumoural capsule should be performed using a knife with a number 11 blade and followed by coagulation of the surface. The internal decompression of the tumoural core might facilitate gently pulling the superior portion of the capsule downwards, where with angle forceps we are able to separate the lateral capsule from the brain tissue (frontal lobe) in cleavage tissue plane, dividing the attachments to the frontal lobe as they are encountered. Microdissection must be employed to remove the tumour in piecemeal fashion. The haemostasis should be done with Oxi® or Surgicell® and bipolar coagulation. The dura mater in the crista galli at the point of tumoural attachment has to be coagulated, the crista galli cut and drilled by means of a diamond burr. This method allows assessment of the other side of the crista galli, where pieces of tumour could not be exposed. We try to close the skull base dural defect with a pericranium patch retaining the arterial feeding of the graft. External lumbar drainage is left for 5 post-operative days.

13.6 Bifrontal Approach for Large Tumours

We recommend bifrontal craniotomy for removal of large tumours. The bifrontal approach permits adequate exposure and allows the surgeon to work on both sides, frontal and temporal, accessing the Sylvian fissure. This allows for the preservation of the olfactory nerves; however, in large tumours they are very difficult to keep intact (Fig. 13.6). The patients should be placed in a supine position, with the head in a neutral position and gently extended towards the floor. After the bifrontal craniotomy using four burr holes, the bone flap is cut with the aid of craniotome Midas Rex® using cutting burrs.