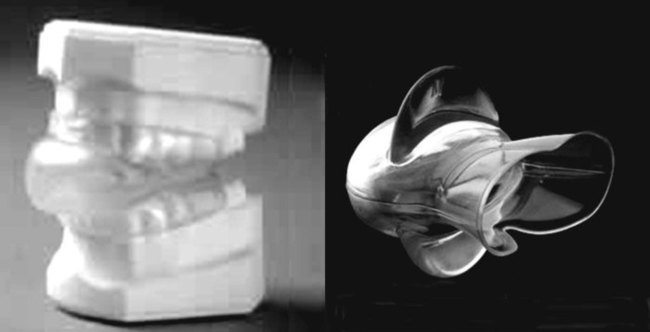

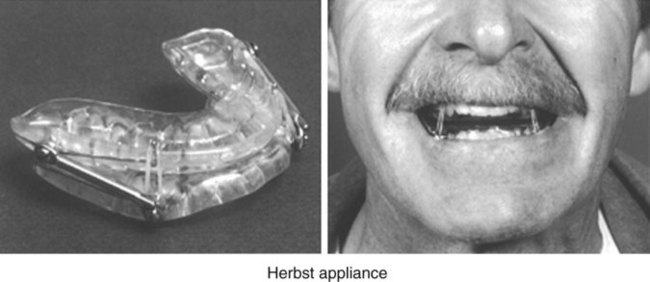

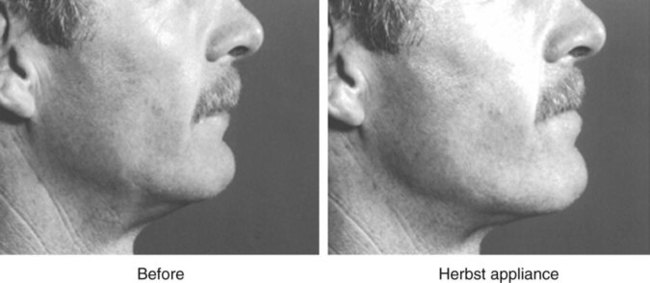

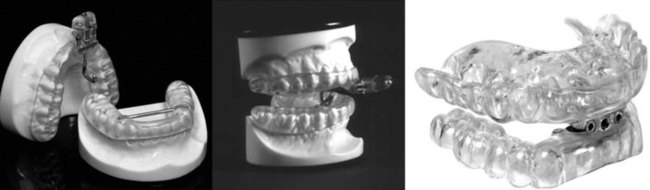

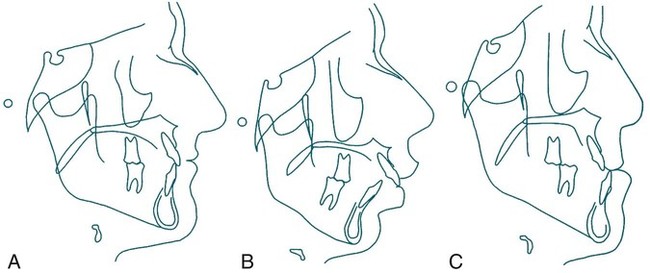

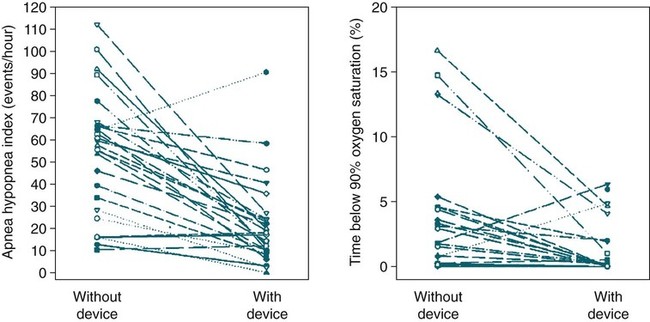

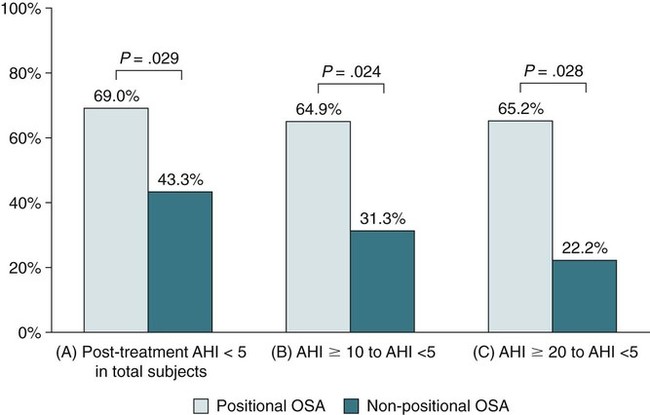

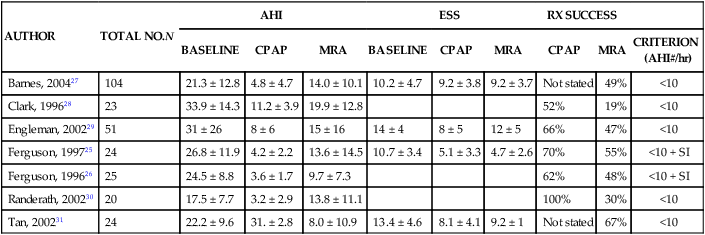

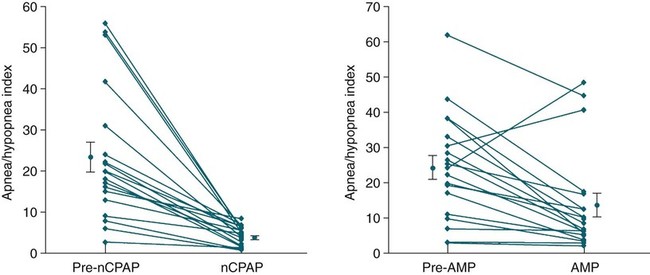

• Before treatment of snoring with an OA, the presence or absence of OSA should be determined. If OSA is present, treatment plans may change based on severity. In addition, the presence of OSA mandates different follow-up. • Treatment with an OA is indicated for patients with primary snoring (when patients do not respond to weight loss or the side sleep position). • Although not as efficacious as CPAP, OAs are indicated for use in patients with mild to moderate OSA who prefer OAs to CPAP, do not respond to CPAP, are not appropriate candidates for CPAP, or fail treatment attempts with CPAP or treatment with behavioral measures such as weight loss or sleep position change. • OAs are not indicated for initial treatment of severe OSA. Positive airway pressure is the treatment of choice for patients with severe OSA. Upper airway surgery may also supersede use of OA in patients for whom surgery is predicted to be highly effective. • OA devices include MRAs and tongue retaining/stabilizing devices. The effectiveness of MRAs is better documented and, at least some studies suggest, better tolerated by patients. • Adjustable custom-fitted MRAs are preferred over monobloc (boil and bite appliances). • A qualified dentist should evaluate potential OA treatment candidates for suitability of OA treatment from the dental standpoint, supervise appliance fitting and adjustment, and see patients for long-term follow-up to determine whether adverse changes in dentition have occurred due to OA treatment. • Follow-up sleep testing after optimal OA adjustment is NOT indicated for treatment of primary snoring but is indicated for treatment of all severities of OSA. Sleep testing may include a PSG, an attended type 3 home sleep test, or unattended type 3 home sleep test (airflow, effort, saturation, pulse, or electrocardiogram). • Follow-up with the treating clinician is needed to assess the patient for signs and symptoms of worsening OSA. If worsening is suspected, repeat sleep testing with the OA in place is indicated. • The presence and severity of OSA must be determined before initiating any type of upper airway surgical treatment for presumed snoring. • Before undergoing surgery, patients should be advised of potential success rates and complications as well as treatment alternatives. • Tracheostomy is the only surgery uniformly effective for severe OSA, although some series suggest MMA may be 45% to 85% effective depending on how surgical success is defined. • MMA is indicated for initial treatment of severe OSA in patients who cannot tolerate or are unwilling to adhere to PAP therapy and in whom OAs have been considered and found ineffective or undesirable. • UPPP does not reliably normalize the AHI in patients with moderate to severe OSA. Patients with severe OSA should be offered PAP treatment. Patients with moderate OSA should initially be offered PAP therapy or an OA. • A PSG is recommended before TNA in children to determine whether OSA is present and to determine the severity. A PSG after TNA is recommended for patients with persistent symptoms of OSA. Many clinicians recommended a post-treatment PSG in children with moderate to severe OSA before TNA (AHI 5–10 or > 10/hr, respectively). An oral appliance (OA) can be defined as a device inserted into the mouth for treatment of snoring or obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).1–5 There are two main types, the tongue retaining (stabilizing) device (TRD/TSD)6–9 (Fig. 20–1) and the mandibular repositioning appliances (MRAs) (Figs. 20–2 to 20–4). The TSD/TRDs hold the tongue in a forward position by retaining the tongue in a suction bulb.6–9 The MRAs are attached to the dental arches and provide variable degrees of bite opening and mandibular advancement. The MRAs are also called mandibular advancing devices (MADs) or mandibular repositioning devices (MRDs). MRAs can come in monobloc (boil and bit) fixed configurations or custom-fitted appliances that can be adjusted to change the amount of mandibular protrusion (advancement). Each candidate for an OA should be examined by a qualified dentist to determine whether an OA is feasible and safe from a dental standpoint. The dental examination should focus on the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), evidence or history of bruxism, quality of dental occlusion, the presence of significant periodontal disease, overall dental health, and protrusive ability. Cephalometrics or dental radiographs may be indicated.10 The patient’s occlusion type should be noted. Three classes (types) of skeletal occlusions are illustrated in Figure 20–5. One might expect that patients with mandibular deficiency (retrognathia) would benefit the most from an OA but the amount of improvement is somewhat unpredictable. The location of airway occlusion during sleep might also be expected to predict the response to OA treatment. Patients with occlusion mainly in the retroglossal area rather than the retropalatal area might be expected to improve the most with a MRA. However, in one study, some patients with upper airway occlusion mainly in the velopharynx also improved with MRA treatment.11 Patients must have a minimal amount of healthy teeth for an MRA. A minimum of 6 to 10 teeth in each arch is needed.1,5 However, treatment with dental implants can permit future MRA treatment in patients with insufficient dentition at the time of evaluation. Patients must be able to open the jaw adequately for OA insertion and must have the ability to voluntarily protrude the mandible. Moderate to severe TMJ disease or inadequate protrusive ability are contraindications. Mild TMJ dysfunction may actually improve with the jaw positioned anteriorly during sleep. Moderate to severe bruxism is also a contraindication in most cases. Bruxism during sleep can actually damage some types of OAs. However, bruxism in some patients improves with adequate treatment of OSA. An experienced dental practitioner should evaluate patients with bruxism for suitability for an OA. A history of bruxism may also alter the choice of the type of OA used. Of note, edentulous patients can be treated with a TRD/TSD. OAs are believed to work by increasing upper airway size. TRDs/TSDs move the tongue forward. MRAs move the tongue and mandible forward, increasing the posterior airspace. By stabilizing the mandibular position, MRAs resist the downward rotation of the mandible with sleep and the accompanying retrusion of the mandible. They may also tense palatal muscles. Some studies have found an increase in upper airway muscle tone with an MRA in place.12 As noted previously, patients with airway closure mainly in the velopharynx may also respond to OA treatment. In agreement with this finding, a study of the effect of an MRA on upper airway size during wakefulness using fiberoptic endoscopy found the most significant increase in airway size was at the velopharynx.13 Another study of videofluoroscopy during sleep found increases in both the retroglossal and the retropalatal airway size during sleep with an MRA in place.14 A number of studies (some controlled) have demonstrated that OA devices are effective in reducing the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) in mild, moderate, and severe OSA.1,2 However, because OAs are less effective than continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) in reducing the AHI to less than 10/hr, CPAP is considered the treatment of choice for moderate to severe OSA. American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) practice parameters2 state that OAs are indicated for treatment of mild and moderate OSA as well as snoring. The practice parameters also state that OAs can be used in severe OSA, although generally considered a third-line treatment after positive airway pressure (PAP) and surgery. A summary of effectiveness in a systematic review of OAs published in 2006 is listed in Table 20–1. Although results differed considerably between studies, OA treatment was found to be successful in about 50% of patients with mild to moderate OSA (using an AHI < 10/hr as the definition of success).1 Of note, some patients with severe OSA can have an impressive reduction in the AHI, although rarely to a value less than 10/hr (Fig. 20–6). TABLE 20–1 Range of Effectiveness of Oral Appliances* AHI = apnea-hypopnea index; OA = oral appliance; OSA = obstructive sleep apnea. *Success is defined as a reduction of the AHI to < 10/hr. From Ferguson KA, Cartwright R, Rogers R, et al: Oral appliances for snoring and obstructive sleep apnea: a review. Sleep 2006;29:244–262. Studies have also documented that OA treatment improves both subjective and objective sleepiness. Using a controlled cross-over design (OA without protrusion as control), Gotsopoulos and coworkers15 found significant improvement in the subjective sleepiness (Epworth Sleepiness Scale decreased from 9 to 7) and objective sleepiness as assessed by the multiple sleep latency test (mean sleep latency increased from 9.1 to 10.3 min). Four variables appear to contribute to the degree of effectiveness of OA treatment of OSA.1,16,17 These include (1) the severity of the OSA, (2) amount of protrusion by the MRA, (3) the presence or absence of positional sleep apnea, and (4) the body mass index (BMI).1 The degree of protrusion of the mandible with MRAs varies typically from 6 to 10 mm or from 50% to 75% of the maximum the patient can voluntarily protrude the mandible on request. One study using the same OA with different protrusions found a reduced AHI with greater protrusion.16 Positional OSA defined as a supine AHI > 2 × lateral AHI predicts that OA will be more effective1,17 (Fig. 20–7). OA treatment also is more effective in mild to moderate OSA (better chance of treatment AHI falling in acceptable range). They also appear to be more effective in the less obese patient. The TSD is manufactured in three prefabricated sizes (small, medium, and large), whereas TRDs are custom-fitted to each patient. The patient inserts the tongue into the device and gently pumps the bulb to apply suction. Once the tongue is inserted, the bulb is released and the tongue is held forward by suction. One study found the TSD to significantly reduce the AHI, although not quite as well as an MRA.9 In addition, the TSD had a lower compliance rate and was more likely to come out during the night. However, the TSD (see Fig. 20–1) may be an affordable alternative for some patients. Purchase of a TSD requires a prescription from a doctor or dentist (approximate price range is $125–$180). Some ideal attributes for an MRA are listed in Table 20–2. The ideal device has coverage of both arches and is adjustable (protrusion can be changed). A recent study compared a custom-made and thermoplastic OA for the treatment of mild OSA. The custom-made device was more effective.18 However, custom-made devices are typically much more expensive. OAs are now viewed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as class 2 medical devices and, as such, must adhere to more detailed standards with special controls.19 A short list of commonly used devices is presented in Table 20–3. A more extensive list is available in Reference 5. A list of FDA-approved devices can be found at http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfPMN/pmn.cfm TABLE 20–2 Attributes of an Ideal Oral Appliance TMJ = temporomandibular joint. Adapted from Bailey DR, Hoekema A: Oral appliance therapy in sleep medicine. Sleep Med Clin 2010;5:91–98. TABLE 20–3 See complete list on FDA website: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfPMN/pmn.cfm After Bailey DR, Hoekema A: Oral appliance therapy in sleep medicine. Sleep Med Clin 2010;5:91–98. After OAs are fabricated, they are usually adjusted by the dentist taking care of the patient for fit and comfort. Patients are then instructed to slowly increase mandibular protrusion until symptoms improve (cessation of snoring and improvement in sleep quality) or until either the maximum protrusion is reached or further advances are not tolerated. In one study, patients were studied during polysomnography (PSG) and a remotely controlled mandibular appliance was advanced until respiratory events were controlled or until further advances were not tolerated.20 The results of the PSG OA titration were highly predictive of the effectiveness of chronic OA treatment with a permanent device. In another study, patients were allowed to adjust their devices at home.21 During a PSG if persistent events were noted, further adjustment during the PSG was performed by protocol (increased protrusion in 1-mm increments). Of the patients completing the protocol, 55% were successfully treated (AHI < 10/hr) after home titration. A total of 64.9% of patients were successfully treated overall. Thus, some patients will likely need further adjustments either during or after a PSG documenting the efficacy of OA treatment. Studies of adherence to OA treatment have almost always relied on patient report. There is a single report of the use of a temperature-sensitive embedded monitor to objectively determine OA use.13 OA adherence rates tend to decrease with the duration of use. One study reported 60% adherence at 1 year and 48% at 2 years.22 Another study reported adherence dropped from 82% to 62% over 4 years.23 The reasons for discontinuing OA included side effects, complications, and lack of efficacy. In a questionnaire study of OA patients 5 years after starting treatment, 64% of respondents were using the OA. Of these, 93% were using the OA more than 4 nights/wk. Of those stopping OA treatment, the causes were discomfort (44%), little or no effect (34%), and the patient changing to CPAP treatment (23%).24 In two cross-over studies of CPAP, adherence to OA was equal to or better than to CPAP.25,26 A number of studies have compared OA and CPAP (Table 20–4).25–31 They show that OAs are not as effective as CPAP but are effective in a significant proportion of patients (19–67%) (Fig. 20–8).1 In some studies listed in Table 20–4, a significant proportion of patients preferred the OA to CPAP. In some studies, improvement in daytime sleepiness was similar with both OA and CPAP treatment even if the AHI was higher with OA than with CPAP. In the study by Barnes and colleagues27 using a cross-over design, 28% preferred CPAP, 41% preferred the OA, and 31% preferred placebo (a tablet). In a study by Ferguson and associates,25 the compliance to an OA and CPAP were similar but patient satisfaction was better with an OA. TABLE 20–4 Comparison of Oral Appliance and Continuous Positive Airway Pressure From Ferguson KA, Cartwright R, Rogers R, et al: Oral appliances for snoring and obstructive sleep apnea: a review. Sleep 2006;29:244–262. The AASM practice parameters for the OA treatment of patients with snoring and OSA2 are listed in Appendix 20–1. The guidelines are summarized in Boxes 20–1 and 20–2. The presence or absence of OSA must be determined before OA treatment. It is important to determine whether OSA or snoring is being treated. If OSA is present, the severity has implications for treatment selection and the probability of success with OA. The OA should be fitted by a qualified dental professional. The treatment goals for snoring are to reduce noise to an acceptable level. For OSA, treatment goals are to reduce the AHI, improve oxygenation, and improve sleep quality. OAs are indicated for primary snoring that does not respond to simple measures such as weight loss, lateral position, and treatment of nasal congestion. OAs are also indicated for mild to moderate OSA. It is acknowledged that CPAP may be more effective. CPAP rather than OA should be the first treatment for severe OSA. If CPAP is not accepted, upper airway surgery or an OA should be considered. Upper airway surgery may also supersede use of OA in patients for whom surgery is predicted to be highly effective. In patients with severe OSA who decline CPAP or surgery, a trial of OA may be reasonable. Another indication for OA would be patients who had failed surgery and do not want CPAP or further surgery. The practice parameters do not mandate repeat sleep testing for OA treatment of snoring. For all severities of OSA, repeat sleep testing with the patient wearing the OA is indicated to document effectiveness (see Box 20–2).2 The practice parameters state either PSG or an attended type 3 cardiopulmonary test is acceptable to assess the efficacy of OA treatment. Recent clinical guidelines for portable monitoring (PM) also state that unattended PM “may be indicated” to determine the adequacy of non-PAP treatment.32 In fact, either unattended cardiopulmonary monitoring or attended PSG is usually used to determine the effectiveness of OA treatment. Follow-up visits with the dentist who fabricated the OA device are also indicated every 6 months, then yearly. This is to ensure side effects are not significant and the amount of protrusion is optimized. Follow-up with the clinician directing sleep apnea treatment is also indicated to be certain OSA symptoms are controlled and do not recur. If symptoms return while the patient is using the OA, repeat sleep testing with OA in place is indicated. The Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS) has recognized certain types of OAs as reasonable and necessary for treatment of OSA. The criteria for reimbursement have been published in the form of local carrier determinations (LCDs) by Durable Medical Administrative Contractors (DMACs). An excerpt from one LCD is listed in Appendix 20–2. Only custom-fabricated mandibular advancement OA (E0486) devices are covered. Coverage requires a face-to-face clinical evaluation prior to a Medicare-covered sleep test. The patient must meet one of the following criteria: (1) AHI ≥ 15/hr or respiratory disturbance index (RDI; events/hr of monitoring time using a home sleep test) ≥ 15/hr or a minimum of 30 events, (2) AHI (RDI) values 5 to ≤ 14 with certain symptoms or disorders (see Appendix 20–2), AHI > 30 or RDI > 30 if the patient cannot tolerate a PAP device or if the treating physician feels PAP treatment is contraindicated. Note that testing for diagnosis cannot be performed by the person or organization supplying the OA. The OA device must be ordered by the treating physician following review of the report of the sleep test. The device is provided and billed for/by a licensed dentist (DDS or DMD). Custom-fabricated devices that work by positioning of the tongue (E1399) or a prefabricated OA (E0485) are not covered. The available research suggests that side effects and complications (Box 20–3) may be grouped as follows: (1) minor and temporary side effects and (2) moderate to severe and continuous side effects. 1. Minor and temporary side effects: These can occur at any stage during treatment, are minor in severity, tend to resolve in a short period of time, or are easily tolerated if they do not resolve and they do not prevent regular use of the appliance. Commonly reported minor and temporary side effects included TMJ pain, myofascial pain, tooth pain, excessive salivation, TMJ sounds, dry mouth, gum irritation, and morning-after occlusal changes. These phenomena were observed in a wide range of frequencies from 6% to 86% of patients.1 Patients undergoing TRD and TSD treatments may report a sore tongue or difficulty with the device slipping off during the night. 2. Moderate to severe and continuous side effects: These can occur at any stage during treatment, are moderate to severe in intensity, tend not to resolve over time, and may result in discontinuation of appliance use. More severe and continuous side effects included TMJ pain, myofascial pain, tongue pain (tongue devices only), gagging (soft palate lifter mostly), tooth pain, gum pain, dry mouth, and salivation.1 Occasionally, these phenomena prevent continued use of the appliance. Several studies have found long-term changes in dental occlusion but the results vary between studies. The changes are relatively mild in most patients. One study found occlusal changes after a mean treatment duration of about 30 months.33 The anteroposterior position of the molars and the inclination of upper and lower incisors changed with MRA treatment. No skeletal changes in mandibular position were noted.

Oral Appliance and Surgical Treatment for Obstructive Sleep Apnea

Oral Appliance Treatment for OSA

Oral Appliances

Evaluation of the Patient

Exclusions and Contraindications

Mechanism of Action of OAs

Effectiveness

MILD TO MODERATE OSA

SEVERE OSA

OA success

57–81%

14–61%

Factors Predicting Effectiveness

Devices

ATTRIBUTE

COMMENT

Adjustable

Allows for modification if dental work is needed.

Titratable

Ability to modify vertical opening or advancement of mandible.

Full tooth coverage

Makes certain upper and lower teeth are fully engaged to prevent tooth movement.

Posterior support

The upper and lower components should have contact in the posterior area for stabilization of TMJ.

Mandibular mobility

Allows free movement of mandible during sleep—beneficial in patients with bruxism.

Adequate lip seal

Improves nasal breathing, prevents drying of teeth.

Adequate tongue space

Prevents collapse of tongue into oropharyngeal airway.

DEVICE

TELEPHONE NUMBER

WEBSITE

Tongue retaining device

800-828-7626

Tongue stabilizing device

800-854-7256 (United States)

http://www.glidewelldental.comGlidewell Dental is the authorized U.S. dealer.

TAP

866-AMI-SNOR

http://www.TAPINTOSLEEP.COM

SUAD Herbst

888-447-6673

Klearway

800-828-7626

http://www.klearway.com

OASYS

888-866-2727

http://www.oasyssleep.com

Titration/Adjustment of OAs

Adherence to OA Treatment

Effectiveness Compared with Other Treatments

AUTHOR

TOTAL NO.N

AHI

ESS

RX SUCCESS

BASELINE

CPAP

MRA

BASELINE

CPAP

MRA

CPAP

MRA

CRITERION

(AHI#/hr)

Barnes, 200427

104

21.3 ± 12.8

4.8 ± 4.7

14.0 ± 10.1

10.2 ± 4.7

9.2 ± 3.8

9.2 ± 3.7

Not stated

49%

<10

Clark, 199628

23

33.9 ± 14.3

11.2 ± 3.9

19.9 ± 12.8

52%

19%

<10

Engleman, 200229

51

31 ± 26

8 ± 6

15 ± 16

14 ± 4

8 ± 5

12 ± 5

66%

47%

<10

Ferguson, 199725

24

26.8 ± 11.9

4.2 ± 2.2

13.6 ± 14.5

10.7 ± 3.4

5.1 ± 3.3

4.7 ± 2.6

70%

55%

<10 + SI

Ferguson, 199626

25

24.5 ± 8.8

3.6 ± 1.7

9.7 ± 7.3

62%

48%

<10 + SI

Randerath, 200230

20

17.5 ± 7.7

3.2 ± 2.9

13.8 ± 11.1

100%

30%

<10

Tan, 200231

24

22.2 ± 9.6

31. ± 2.8

8.0 ± 10.9

13.4 ± 4.6

8.1 ± 4.1

9.2 ± 1

Not stated

67%

<10

OA Treatment Guidelines

Follow-up

Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services Coverage of OA Treatment

Side Effects and Complications

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Oral Appliance and Surgical Treatment for Obstructive Sleep Apnea