CHAPTER 146 Osseous Tumors

Non-Neoplastic Lesions

Fibrous Dysplasia

FD is an aberration in normal bone development that results from a defect in osteoblastic differentiation and maturation originating in a mesenchymal precursor.1,2 The disease is characterized by foci of abnormal fibro-osseous proliferation that can affect any area of the calvaria and occurs in three distinct clinical patterns: (1) monostotic, the most common form with single bone involvement; (2) polyostotic, with multiple bone involvement; and (3) as part of McCune-Albright syndrome, a rare variant of the polyostotic form with pigmentation and endocrinologic abnormalities.2–5 The disease commonly occurs in the first 3 decades of life, particularly in late childhood and early adolescence.

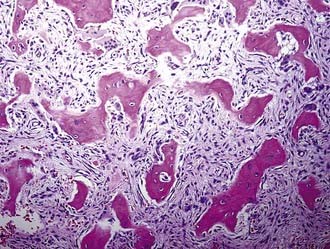

FD is considered an abnormal overgrowth of bone. Recent evidence has shown that activating mutations of G proteins in osteoblastic cells result in increased activation of adenylate cyclase, thereby leading to overproduction of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and culminating in increased cell proliferation and aberrant cell differentiation.6–8 Interleukin-6 may also increase intracellular cAMP, which can result in osteoclast proliferation and thus contribute to the bone lesions seen in FD.9 Microscopically, FD characteristically appears as woven bone interspersed between areas of fibrous tissue (Fig. 146-1).

FIGURE 146-1 Histology of fibrous dysplasia (hematoxylin-eosin, ×100). Woven bone is interspersed within areas of fibrous tissue.

On skull radiographs and computed tomography (CT), the lesions have a characteristic “ground-glass” appearance. They may appear sclerotic (35% of cases), cystic (25% of cases), or as a mixture of the two (40% of cases).10 In thinner bones of the cranium (e.g., temporal, frontal, and maxillary bones), the bone undergoes rapid expansion that results in lytic, cavitary lesions (Fig. 146-2). Thicker bones of the skull (e.g., sphenoid) tend to undergo a more diffuse sclerotic reaction.2 CT is an effective imaging tool for detection of the disease, although magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be a useful adjunct for identifying affected neurovascular structures.

Clinically, the FD lesion progresses as a painless, nonmobile mass, and orbitocranial swelling can reach significant proportions and result in severe cosmetic deformities. Lesions involving the petrous portion of the temporal bone can give rise to conductive hearing loss via stenosis of the external auditory canal. Nasal obstruction may result from FD involvement of the frontal, ethmoid, sphenoid, or maxillary bones. Skull base involvement may result in diplopia, facial pain or numbness, and headaches. Visual disturbance occurs when the optic canal is involved.2

Treatment of FD ranges from observation to aggressive surgical intervention. Medical treatment, primarily with bisphosphonates, has been reported to be successful.11,12 When feasible, surgical resection with cosmetically acceptable reconstruction is advocated.3 In cases of optic canal involvement (particularly with visual loss), early and aggressive surgical treatment is warranted, and some authors advocate prophylactic enlargement of the optic canals.13 Radiotherapy for FD has been strongly discouraged because the incidence of secondary malignancy is high. FD has also been reported to spontaneously degenerate to more malignant subtypes such as osteosarcoma and, less commonly, to fibrosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, or malignant fibrous histiocytoma.14,15

Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis

LCH is characterized by proliferation and accumulation of histiocytes (i.e., Langerhans cells). LCH can involve any bone in the skeletal system, but the skull is most frequently affected. Three clinical syndromes are associated with LCH: (1) eosinophilic granuloma, (2) Hand-Schüller-Christian disease (with a triad that includes skull lesions, exophthalmos, and diabetes insipidus), and (3) Letterer-Siwe disease (disseminated lesions involving multiple visceral organs).16 In general, the disease is more common in children than adults.

LCH results in bony destruction with replacement of the bone marrow by Langerhans cells, eosinophils, neutrophils, and macrophages. Although its etiology is poorly understood, LCH is thought to be a disorder of the immune system.17,18 There is a neoplastic component because the cells are clonal in origin.16

LCH lesions develop in the diploic spaces of the skull. On plain radiographs they appear as punched-out lytic lesions with a well-defined margin. These lytic lesions may contain a fragment of normal bone, referred to as a sequestrum. Multiple lytic lesions are seen in Hand-Schüller-Christian disease. LCH has also been reported to occur in the skull base, including the clivus.19,20 Here, the disease may result in cranial nerve palsies and brainstem dysfunction. CT can also be used for diagnostic purposes and may be better than plain radiographs at showing bony destruction. MRI is useful for assessing any bone marrow or soft tissue involvement (Fig. 146-3).

The disease is more common in children but can strike at any age. Clinically, patients often complain of localized pain. Petrous bone involvement may result in otorrhea or hearing loss. Some LCH lesions are asymptomatic, which can lead to a delay in diagnosis. Eosinophilic granuloma is the most common form of the disease and is manifested as a monostotic lesion in the skull. The most severe form of the disease, Letterer-Siwe disease, occurs in children younger than 2 years, in whom fever, anemia, hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, and skin lesions develop.17

The natural history of LCH is variable. Some lesions will regress spontaneously but may recur years later.21 Some isolated bone lesions may be treated by surgical curettage or direct intralesional injection of methylprednisolone.16 In most patients with cranial involvement, systemic chemotherapy may be warranted, and the agents typically used include vinblastine, etoposide (VP-16), prednisone, methotrexate, and 6-mercaptopurine. Local irradiation has also been used. Patients with solitary lesions have a good prognosis. Poor prognostic indicators include onset before 2 years of age, extensive visceral or extraosseous involvement, anemia, and thrombocytopenia.16,21,22

Aneurysmal Bone Cyst

ABCs are benign osteolytic, multicystic expansile lesions of bone that generally develop in the second or third decade of life. ABCs of the skull are rare and account for 2.5% to 6% of skull pathologies.23 The origin of ABCs is unknown, but one hypothesis suggests that an underlying arteriovenous anomaly results in the dilated vascular spaces.24–26 Secondary development of an ABC has also been described in connection with other initial pathologies.23 The histologic characteristics of ABCs include cavernous, pseudovascular channels consisting of connective tissue with giant cells and trabecular bone.4

Clinically, patients have a tender, palpable scalp mass, although pain is not always present. The treatment of choice is complete resection because subtotal resection is associated with a 50% recurrence rate.23,24,27,28 Preoperative angiographic embolization is recommended as a result of the high vascularity of these lesions.

Benign Tumors

Hemangioma

Hemangiomas are benign tumors of blood vessels. In the skull they are of the cavernous type and consist of large dilated blood vessels separated by fibrous tissue. Hemangiomas of the skull are observed in patients of all ages but are most commonly found in the fourth decade of life.29 Hemangiomas account for 0.2% of osseous tumors.30 Their cause is unknown, although they may be associated with antecedent trauma.29 These tumors develop in the diploic spaces with a vascular supply, typically from the middle meningeal artery or the external carotid artery.

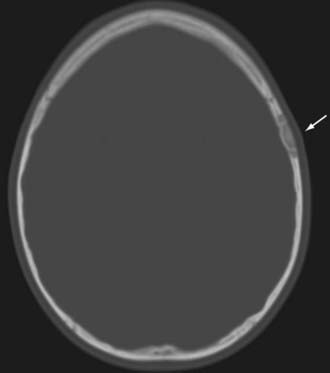

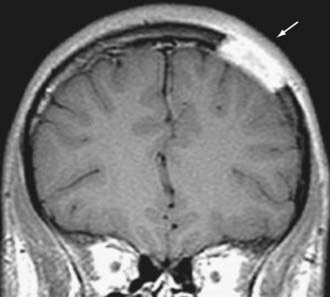

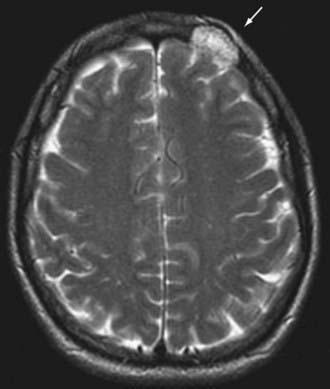

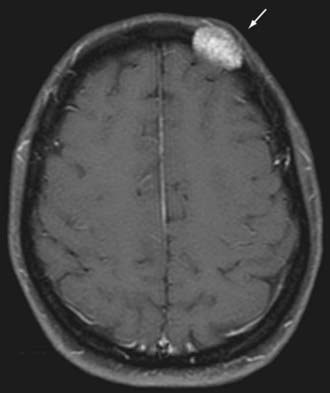

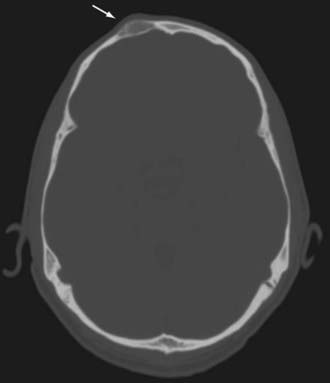

Radiographically, hemangiomas of the skull appear as solitary cystic lesions with a sclerotic rim. Their classic description includes a “honeycomb” or “sunburst” pattern as seen on plain radiographs. On CT, they appear as lytic, expansile, and “bubbly” lesions with a sclerotic rim30,31 (Fig. 146-4). On T1-weighted MRI, hemangiomas generally appear isointense or hypointense. On T2-weighted MRI, they appear hyperintense (Fig. 146-5). Hemangiomas generally show avid contrast enhancement (Fig. 146-6).

FIGURE 146-4 Axial CT scan showing a right frontal hemangioma (arrow). Note the lytic and expansile nature of the lesion.

In most patients, hemangiomas are asymptomatic, slow-growing masses, but they may become symptomatic if they compress adjacent structures, such as the meninges. They may also cause isolated skull pain and be palpable masses. The treatment of choice of symptomatic hemangiomas is surgical excision.32

Osseous Meningiomas

Osseous meningiomas (also known as hyperostosing en plaque meningiomas) are primarily a disease of bone. Historically, the nomenclature regarding purely calvarial meningiomas has been confusing. They have been described as occurring in three varieties.33 Tumors that are purely extracalvarial are type I, purely calvarial tumors are type II, and calvarial tumors with extracalvarial extension are type III. Each category is further divided into convexity (C) or skull base (B) subtypes based on their anatomic location. These tumors occur in males and females, with a slight female preponderance, and typically develop in the fifth decade of life.34 Osseous meningiomas represent 1% to 2% of all meningiomas.35

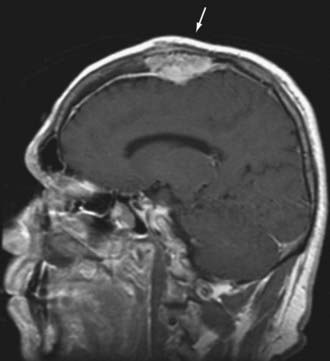

Osseous meningiomas may be osteoblastic or osteolytic, which influences their radiographic appearance. Osteoblastic meningiomas are the most common subtype, and they induce hyperostosis. On plain skull radiographs and CT, these lesions appear hyperdense with areas of calcification and atypical vascular markings.35 On CT, the lesion may have a “ground-glass” appearance similar to that seen in FD (as described earlier).36 Osteolytic meningiomas, which are much rarer, may be manifested as lytic skull lesions. The skull may appear thinned and expanded with disruption of its inner and outer tables. On MRI, both subtypes appear hypointense on T1-weighted images and hyperintense on T2-weighted images. They exhibit avid enhancement after the administration of contrast material (Fig. 146-7).

FIGURE 146-7 Sagittal contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance image showing an intraosseous meningioma (arrow).

Histopathologic evaluation of these tumors often shows classic features of meningioma, including psammoma bodies and eosinophilic tumor cells with whorls. The most common histologic type is meningotheliomatous meningioma, although atypical or malignant characteristics may be present.33

These tumors may develop at either the convexity or skull base. They are generally solitary, and symptoms depend on tumor location and the extent of tumor involvement of the calvaria. Most of these tumors are slow growing and painless, but initial symptoms such as neurological deficits, seizures, hearing loss, tinnitus, dizziness, and cranial nerve deficits have been reported.35 Common locations for the variety occurring at the convexity include the periorbital and frontoparietal regions.37 Skull base lesions may also involve the nasal cavity or sinuses. The treatment of choice is wide surgical excision, if possible. Durable reconstruction is also best performed at the time of the initial operation. In the event of subtotal resection of benign meningiomas, observation with serial imaging is an acceptable treatment strategy. However, for atypical or malignant tumors, adjuvant chemotherapy has been advocated.37

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree