Pathologic Reflexes

Pathologic reflexes are responses not generally found in the normal individual. Some are responses that are minimally present and elicited with difficulty in normals but become prominent and active in disease, while others are not seen in normals at all. Many are exaggerations and perversions of normal muscle stretch and superficial reflexes. Some are related to postural reflexes or primitive defense reflexes that are normally suppressed by cerebral inhibition but become enhanced when the lower motor neuron is separated from the influence of the higher centers. Others are responses normally seen in the immature nervous system of infancy, then disappear only to reemerge later in the presence of disease. A decrease in threshold or an extension of the reflexogenic zone plays a role in many pathologic reflexes.

Descending motor influences normally control and modulate the activity at the local, segmental spinal cord level to insure efficient muscle contraction and proper coordination of agonists, antagonists, and synergists. Disease of the descending motor pathways causes loss of this normal control so that activity spills from the motor neuron pool responsible for a certain movement to adjacent areas, resulting in the recruitment into the movement of muscles not normally involved. Some pathologic reflexes may also be classified as “associated movements,” related to such spread of motor activity. Whether a certain abnormal response would be best classified as a reflex or an associated movement is not always clear. Responses that are more in the realm of an associated movement are sometimes referred to clinically as reflexes (e.g., the Wartenberg thumb adduction sign, an associated movement, is sometimes called a Wartenberg reflex).

Most pathologic reflexes are related to disease involving the corticospinal tract and associated pathways. They also occur with frontal lobe disease and occasionally with disorders of the extrapyramidal system. There is a great deal of confusion regarding names of reflexes and methods of elicitation, and in many cases there has been significant drift away from the original description. Many of the responses are merely variations in the method of eliciting the same responses, or modifications of the same reflex. The typical reflex pattern with lesions involving the corticospinal tract, the upper motor neuron syndrome, is exaggeration of deep tendon reflexes (DTRs), disappearance of superficial reflexes, and emergence of pathologic reflexes (Table 28.3).

Fontal release signs (FRS) are reflexes that are normally present in the developing nervous system, but disappear to a greater or lesser degree with maturation. While normal in infants and children, when present in an older individual they may be evidence of neurologic disease, although some may reappear in normal senescence. Many of these are exaggerations of normal reflex responses. Responses often included as FRS include the palmomental reflex (PMR), grasp, snout, suck, and others.

Frontal release signs occur most often in patients with severe dementias, diffuse encephalopathy (metabolic, toxic, postanoxic), after head injury, and other states in which the pathology is usually diffuse but involves particularly the frontal lobes or the frontal association areas. The significance and usefulness of some of these release signs or primitive reflexes has been questioned. The PMR is commonly seen in normal individuals. The Hoffman finger flexor reflex and its variants, which are sometimes classified as FRS and sometimes as corticospinal signs, are similarly present in a significant proportion of normal individuals. Clearly, these reflexes are a normal phenomenon in a significant proportion of the healthy population. They must be interpreted with caution and kept in clinical context. Even when such reflexes are briskly active in an appropriate clinical setting, the primitive reflexes do not have great localizing value, suggesting instead the presence of diffuse and widespread dysfunction of the hemispheres.

PATHOLOGIC REFLEXES IN THE LOWER EXTREMITIES

Pathologic reflexes in the lower extremities are more constant, more easily elicited, more reliable, and more clinically relevant than those in the upper limbs. The most important of these responses may be classified as (a) those characterized in the main by dorsiflexion of the toes, and (b) those characterized by plantar flexion of the toes. The most important pathologic reflex by far is the Babinski sign, and a search for an upgoing toe is part of every neurologic examination. Searching for upper-extremity pathologic reflexes is much less productive and often omitted.

Corticospinal Responses Characterized in the Main by Extension (Dorsiflexion) of the Toes

The Babinski Sign

In the normal individual, stimulation of the skin of the plantar surface of the foot is followed by plantar flexion of the toes (Figure 29.2). In the normal plantar reflex, the response is usually fairly rapid, the small toes flex more than the great toe, and the reaction is more marked when the stimulus is along the medial plantar surface. In disease of the corticospinal system there may be instead extension (dorsiflexion) of the toes, especially the great toe, with variable separation or fanning of the lateral four toes: the Babinski sign or extensor plantar response (Figure 30.1). The Babinski

sign has been called the most important sign in clinical neurology. It is one of the most significant indications of disease of the corticospinal system at any level from the motor cortex through the descending pathways.

sign has been called the most important sign in clinical neurology. It is one of the most significant indications of disease of the corticospinal system at any level from the motor cortex through the descending pathways.

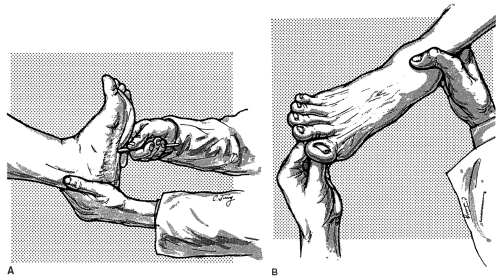

The Babinski sign is obtained by stimulating the plantar surface of the foot with a blunt point, such as an applicator stick, handle of a reflex hammer, a broken tongue blade, the thumbnail, or the tip of a key. Strength of stimulus is an important variable. It is not true that the stimulus must necessarily be deliberately “noxious,” although most patients find it at least somewhat uncomfortable even if the examiner is trying to be considerate. When the response is strongly extensor only minimal stimulation is required. The stimulus should be firm enough to elicit a consistent response, but as light as will suffice. Some patients are very sensitive to plantar stimulation and only a slight stimulus will elicit a consistent response; stronger stimuli may produce confusing withdrawal. If the toe is briskly upgoing, merely a fingertip stimulus may elicit the response. If no response is obtained, progressively sharper objects and firmer applications are necessary. Although some patients require a very firm stimulus, it is not necessary to aggressively rake the sole as the opening gambit. Both tickling, which may cause voluntary withdrawal, and pain, which may bring about a reversal to flexion as a nociceptive response, should be avoided.

Plantar stimulation must be carried out far laterally, in the S1 root/sural nerve sensory distribution. More medial plantar stimulation may fail to elicit a positive response when one is present. Far medial stimulation may actually elicit a plantar grasp response causing the toes to flex strongly. The stimulus should begin near the heel and be carried up the side of the foot at a deliberate pace, not too quickly, usually stopping at the metatarsophalangeal joints. The response has usually occurred by the time the stimulus reaches the midportion of the foot. If the response is difficult to obtain, the stimulus should continue along the metatarsal pad from the little toe medially, but stopping short of the base of the great toe. The most common mistakes are insufficiently firm stimulation, placement of the stimulus too medially and moving the stimulus too quickly, so that the response does not have time to develop. The only movements of real significance are those of the great toe. Fanning of the lateral toes without an abnormal movement of the great toe is seldom of any clinical significance, and an absence of fanning does not negate the significance of great toe extension.

The patient should be relaxed and forewarned of the potential discomfort. The knee must be extended; an upgoing toe may be abolished by flexion of the knee. The best position is supine, with hips and knees in extension and heels resting on the bed. If the patient is seated, the knee should be extended, with the foot held either in the examiner’s hand or on her knee. The response may sometimes be reinforced by rotating the patient’s head to the opposite side.

Usually, the upward movement of the great toe is a quick, flicking motion sometimes mistaken for withdrawal by the inexperienced. The response may be a slow, tonic, sometimes clonic, dorsiflexion of the great toe and the small toes with fanning, or separation, of the toes. The slow great toe movement has been described as a “majestic rise.” The nature of the stimulus may be related to the speed of the toe movement; primarily proprioceptive stimuli (e.g., Gonda, Stransky, Szapiro) are more apt to be followed by a slow, tonic response; exteroceptive stimuli by a brief, rapid extension. There may occasionally be initial extension, followed by flexion; less often brief flexion precedes extension. There may be extension of only the great toe, or extension of the great toe with flexion of the small toes.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree