CHAPTER 286 Pediatric Spondylolisthesis

Spondylolisthesis was first described more than 200 years ago when a Belgian obstetrician combined the Greek roots for vertebra (spondylos) and slippage (listhesis) to explain an osseous protuberance found to compromise the birth canal during delivery.1 After almost a century, the term came to characterize forward slippage of L5 on S1. Initial theories of its cause were based on the presumed effects of axial body weight on the lumbar-sacral-pelvic junction with resultant subluxation of the facet joint.2 Similar mechanistic hypotheses prevailed over the following 100 years, such as injury or trauma as inciting events in the setting of underlying lumbosacral defects or excessive body weight as in Blake’s description of a 26-year-old multiparous woman who experienced a weight gain of 100 lb before slippage was detected.3,4 The current understanding of spondylolisthesis is based on the etiology, severity, and likelihood for progression and stems from the classification scheme provided by Newman in the 1960s.5

Epidemiology

Spondylolisthesis is a relatively common problem, with more than 30% of lumbar fusions being performed for this diagnosis.6 Each type of spondylolisthesis has differences in demographics, natural history, severity, levels involved, and treatment considerations. The pediatric population is most affected by the dysplastic and isthmic types. Degenerative spondylolisthesis is more commonly seen in women and at the L4-5 level, whereas isthmic spondylolisthesis most commonly affects L5-S1 and is seen predominantly in men. Hereditary factors appear to play some role in the development of congenital and isthmic spondylolisthesis.7–11 Certain types of isthmic spondylolisthesis contain a dysplastic elongated pars, which has been found to have a strong familial component.12 Most agree, however, that environmental factors play a major role in the development and progression of spondylolisthesis. Slip progression has been linked with the adolescent growth spurt, a greater degree of slippage on initial evaluation, and lumbosacral kyphosis. Factors associated with a higher risk for progressive slippage include younger age (by demonstration of decreased skeletal maturity), slippage of greater than 50%, slip angle greater than 40 to 50 degrees (with 0 to 10 degrees being normal), female gender, a dome-shaped sacrum, and a dysplastic lumbosacral junction. Diagnosis after the onset of adulthood portends a lower rate of significant progression.

Classification

Newman classified spondylolisthesis into five groups in 1963 (Table 286-1).5 This was later published by Wiltse, and colleagues in 1976.13

TABLE 286-1 Newman’s Classification of Spondylolysis

| DYSPLASTIC |

| ISTHMIC |

| DEGENERATIVE |

| TRAUMATIC |

Forced hyperflexion (resulting in pure dislocation) or hyperflexion combined with compression or axial translation |

| PATHOLOGIC |

Modified from Wiltse LL, Newman PH, Macnab I. Classification of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1976;117:23-29.

Dysplastic

Dysplastic (congenital) spondylolisthesis results from a congenital defect at the L5-S1 articulation. Facet defects such as hypoplasia or malorientation or sacral deficiency results in vertebral subluxation. Although some degree of compromised integrity exists, the pars interarticularis is intact in children with congenital spondylolisthesis. Most patients have an abnormal orientation of the facets and a dome-shaped sacral promontory with lack of the normal buttress effect provided by the posterior elements. In contrast to other types of spondylolisthesis, progression is common because the dysplastic facets permit further slippage.14 This anterior translation may result in neuroforaminal stenosis and compression of the exiting nerve root and become symptomatic with radiculopathy. If the slippage progresses to spondyloptosis, severe neurological conditions such as cauda equina syndrome can occur as the nerve roots become entrapped by the lamina, intact pars interarticularis, and the sacral dome (Fig. 286-1). Dysplastic spondylolisthesis occurs approximately twice as frequently in females as males and was found to account for 14% to 21% of cases in two large series.15–17 It can be subdivided into subtypes A to C (Table 286-2, Figs. 286-2 to 286-7).

TABLE 286-2 Types of Dysplastic Spondylolysis

| SUBTYPE A |

| SUBTYPE B |

| SUBTYPE C |

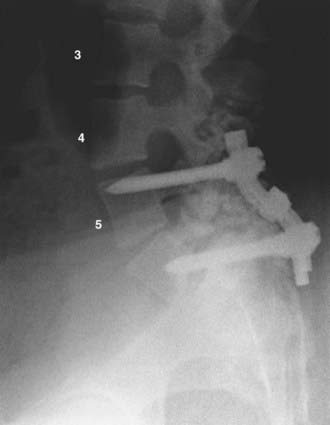

FIGURE 286-3 Lateral plain radiograph of the patient in Figure 286-2 after L5-S1 transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion with reduction and decompression. The S1 screws traverse the L5 inferior end plate.

FIGURE 286-4 Anteroposterior radiograph of the patient in Figure 286-2 treated by L5-S1 transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion with reduction and decompression.

FIGURE 286-5 Anteroposterior plain radiograph after Bohlman fusion for high-grade dysplastic spondylolisthesis.

Isthmic

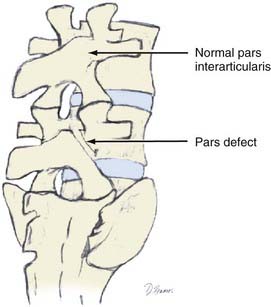

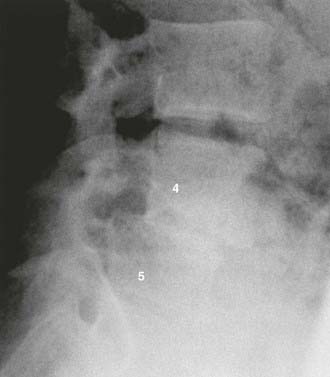

Isthmic spondylolisthesis refers to vertebral subluxation caused by a defect in the pars interarticularis of the posterior spine (spondylolysis) (Figs. 286-8 and 286-9). The pars interarticularis plays a strategic role in the configuration of the spine in that it supports the anterior and posterior columns through the connection of the pedicle with the lamina and facet joints. Because it provides such functional integrity to the lumbar spine, if compromised it may allow subluxation.7,18–21

There are three subclassifications of isthmic spondylolisthesis (Table 286-3). The first is thought to result from stress fractures within the pars interarticularis (subtype A). The second type (subtype B) is an elongation rather than an actual break in the pars. Subtype C, the most uncommon type, refers to an acute fracture of the pars.

TABLE 286-3 The Three Subclassifications of Isthmic Spondylolisthesis

| SUBTYPE A |

| SUBTYPE B |

| SUBTYPE C |

Approximately 90% of cases result from an L5 pars defect and involve the L5-S1 joint. The second most common defect arises from compromise of the L4 pars, which leads to L4-5 anterior subluxation.7,18–24

These defects typically occur in adolescents and represent the most common type of spondylolisthesis in this age group. Males are more commonly affected than females; however, in those with high-grade isthmic spondylolisthesis, females are affected four times more commonly than males, with the highest rates reported in Alaskan female Eskimos. Hereditary factors appear to play a role in the isthmic types in that an increased incidence in first-degree relatives ranging from 19% to 69% has been cited in different series. When compared with the dysplastic types with abnormal vertebral architecture, isthmic spondylolisthesis is less likely to progress because dysplastic features are not a characteristic of this type (Figs. 286-10 and 286-11).

Degenerative

Although Newman is credited with the term degenerative spondylolisthesis, Junghanns first described lumbar spondylolisthesis without a pars defect as “pseudospondylolisthesis” in the 1930s.25,26 As would be expected, this condition primarily affects the older population. Rosenberg and associates’ studies of 20 skeletons and 200 patients with degenerative spondylolisthesis found this condition to occur up to six times more frequently at the L4-5 level than at adjoining levels.27,28 Lower extremity symptoms were described in 153 patients, 85 of whom had neurological findings on objective evaluation. Of these patients, signs and symptoms requiring hospitalization developed in 39, and 29 eventually required operative treatment after conservative measures failed.27 In addition, a fourfold increase in listhesis was found in patients with sacralization of L5.

Women are affected five times more frequently than men and black women three times more frequently than white women. The superior facet of the affected level often undergoes hypertrophic changes that cause stenosis of the lateral recess, thereby compounding the already present compromise in central canal diameter. Although the percentage of slippage was not reliably correlated with clinical symptoms, Rosenberg found that at the L3 level, even a small amount of listhesis may produce pronounced symptoms. Spondylolisthesis was associated with a higher lumbosacral angle, and the most common complaint was pain in the back, buttock, or thigh. The symptoms of spondylolisthesis may not remain constant and often occur in discrete periods. The sitting position was noted to improve symptoms in many cases. According to Rosenberg, the L5 nerve root provided the most common source of objective physical findings when present.27

Hormonal factors resulting in ligamentous laxity may contribute to the higher incidence of degenerative spondylolisthesis in women.29 This was concluded in part by Imada and associates, who demonstrated in their review of women who had undergone oophorectomy a three times higher incidence of degenerative spondylolisthesis.30 Nadaud and colleagues, however, failed to find evidence of estrogen receptors on facet joint capsular ligaments in their review of 14 patients who underwent spinal fusion surgery.31 Grobler and coworkers demonstrated the role of anatomic morphology when they compared computed tomography (CT) scans of facet joints affected by degenerative spondylolisthesis with scans of normal lumbar spines.32 They found a more sagittally oriented L4-5 facet joint in patients with degenerative spondylolisthesis than in normal individuals, as well as a greater transverse articular dimension and joint surface depth. Osteophyte formation within the joint may be primarily responsible for these findings.

In a prospective study of 40 patients with a minimum 5 years of follow-up, Matsunaga and coauthors reviewed the natural history of degenerative spondylolisthesis.33 They determined that women with a mean age of 55 were most commonly affected and that L4 was most commonly involved (87.5% versus 10% at L5). In this study, 30% of the patients experienced progression of slippage by 5% or greater, with a mean initial slippage rate of 12.4% per 5 years in the progression group and 14.5% per 5 years in the group without progression. Although there was no correlation between gender and progression of slippage, a positive correlation was found among activity, particularly repetitive anterior flexion, and progression of slippage. Within the group experiencing progression, 75% were involved in activities requiring repetitive flexion, whereas only 10% of the group without progression performed similar activities. They were unable to demonstrate a significant difference in lumbosacral angle, lamina angle, or facet inclination angle between the groups. Factors not found to be associated with progression of slippage included spur formation of the involved vertebral body, sclerosis of the end plates, and ossification of the ligaments. Using Carter’s criteria, more patients with degenerative spondylolisthesis were found to have joint laxity than normal individuals. Progression of slippage did not correlate with clinical deterioration. The most common symptoms were low back pain and gluteal pain, which were present in 98% of patients. Lower extremity pain and numbness were also present in 48% of patients, whereas intermittent claudication was seen in 13% and one patient had bowel and bladder dysfunction. In a follow-up review of nonsurgically treated patients over a 10-year period by the same authors, progression of spondylolisthesis occurred in 34% of patients.34 They again were unable to correlate this progression with clinical symptoms. All patients who were noted to be neurologically intact at initial evaluation remained so at the 10-year follow-up. However, 83% of the patients with initial neurological symptoms experienced further neurological deterioration, thus providing evidence for recommending early treatment in symptomatic individuals (Figs. 286-12 and 286-13).

Traumatic

Although bracing alone may suffice for the treatment of many fractures of the posterior element, open reduction with segmental fixation and fusion is most often required in patients with progressive displacement of the involved level (Figs. 286-14 to 286-18).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree