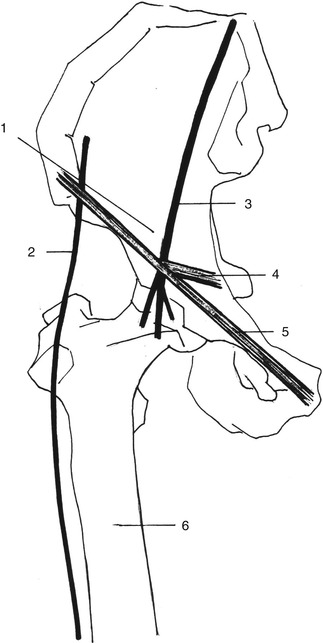

Fig. 36.1

Schematic drawing of the posterior aspect of the hip and femur to illustrate the site of entrapment of the sciatic nerve. 1 Superior gluteal nerve, 2 piriformis muscle, 3 femur greater trochanter, 4 sciatic nerve

The most common entrapment syndrome of the sciatic nerve is the piriformis syndrome, representing the cause of nondiscal sciatica in almost 70 % of 239 patients in a recent report by Filler et al [6]. Usually, the lumbosacral plexus is located on the ventral surface of the piriformis muscle (PM), and the sciatic nerve passes along the anterior surface of the muscle and then along its inferior border, exiting the pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen below the PM. The entrapment syndrome can be caused by PM hypertrophy, inflammation, or posttraumatic changes (hematoma, fibrosis).

The most prominent symptom is pain in the buttock radiating down in the posterior thigh; weakness, numbness, and paresthesias are generally mild if present [6, 23]. Stretching of the piriformis muscle against the sciatic nerve by passive internal rotation and adduction of the thigh (Freiberg sign) or active contraction of the piriformis muscle by active external rotation and abduction of the thigh against resistance (Pace sign) have been proposed as diagnostic signs. MRI neurography of the lumbosacral plexus and sciatic nerve might allow a more accurate diagnosis in suspected cases and can exclude other possible causes of sciatic nerve lesion [6, 13]: unilateral hyperintensity of the sciatic nerve at the sciatic notch appears to be a relatively high specific sign of piriformis syndrome [6].

CT- or MRI-guided injection of a local anesthetic (Marcaine) is a procedure with diagnostic and sometimes also therapeutic values: Filler et al. [6] reported permanent relief in 37 patients (23 % of all patients) after one or two injections, possibly due to relief of muscle spasm. Excellent or good outcome was reported in 82 % of surgically treated patients: the surgical procedure consisted of a transgluteal approach to the piriformis muscle, with resection of the muscle and neuroplasty of the sciatic nerve.

In a recent review by Smoll [19], there is a high prevalence of piriformis and sciatic nerve anatomical variants, both in surgical case series (16.2 %) and in cadaveric studies (23 %). The anomaly can be the exit of the sciatic nerve, or of one of its branches, through or above the PM. The difference between the “surgical” and the “normal” population was not found to be significant, indicating that the anomaly may not be fundamental in the pathogenesis of piriformis syndrome. The anatomical variants must be considered in order to avoid the potential complications they may have on medical or surgical interventions [19].

36.3 Entrapment of the Lateral Femoral Cutaneous Nerve

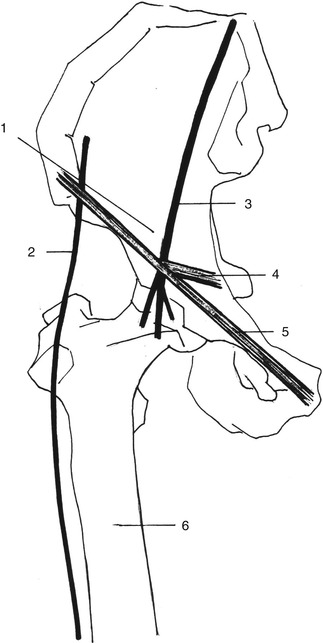

The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (LFCN) is primarily a sensory nerve that innervates the skin of the anterolateral aspect of the thigh. The origin of this nerve is, generally, from the ventral branch of the second lumbar nerve, then it passes behind the posterior aspect of the psoas muscle, runs in the iliac fossa beneath the fascia of the iliac muscle, and reaches a fibro-osseous tunnel delimited by the anterior superior iliac spine, the anterior inferior iliac spine, and the inguinal ligament (Fig. 36.2). The nerve exits the pelvis crossing a narrow tunnel, between two slips of the attachment of the inguinal ligament, then pierces the fascia lata becoming superficial. After running for 2–3 cm in the fascia lata, laterally to the sartorius muscle, it gives the terminal gluteal and femoral branches that have a highly variable location and course [3].

Fig. 36.2

Schematic drawing of the anterior aspect of the hip and femur to illustrate the sites of entrapment of the femoral and lateral femoral cutaneous nerves. 1 Lacuna musculorum, 2 lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, 3 femoral nerve, 4 iliopectineal ligament, 5 inguinal ligament, 6 femur

Meralgia paresthetica (MP) is an entrapment of the LFCN at the level of the inguinal ligament with an incidence rate of about 4.3/10.000 persons/year, prevalently in males and between 41 and 60 years. It is often associated with carpal tunnel syndrome, pregnancy, and obesity [8, 21] and is mostly unilateral, but 8–12 % of patients experience bilateral symptoms [11]. Clinically, MP is characterized by dysesthesia or anesthesia, intermittent or persistent burning, coldness, lightning pain, tingling, and hair loss in the anterolateral aspect of the thigh. Usually, patients complain of a characteristic increased sensitivity to clothing.

The LFCN can also be irritated by the wearing of tight clothes or belts, by prolonged standing or walking, by an abdominal mass [8], and by iatrogenic causes like surgical scars, iliac crest bone graft removal, laparoscopic hernia repair, and prolonged wrong position during a surgical operation. The nerve can be also the site of a metabolic neuropathy correlated with diabetes mellitus, alcoholism, or lead poisoning [22].

The diagnosis of MP is primarily clinical, the neurological dysfunction being only sensory. It is necessary to exclude any other cause of compression along the course of the nerve. Lumbar and pelvis computerized tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance (MR) imaging should exclude L2–L3 pathology and pelvic masses. Electrophysiology, as conduction studies and somatosensory-evoked potentials, can confirm the diagnosis of an LFCN lesion and, above all, exclude other causes of thigh pain and numbness.

The initial treatment of MP is nonoperative. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, local injection of steroids and anesthetics, weight loss, and avoidance of local physical constricting factors can be recommended [18]. Conservative treatment reduces symptoms to an acceptable level, and long-lasting relief is achieved in 60–90 % of cases. Surgical therapy is necessary when complaints are intractable and disabling. One method advocates the transection of the LFCN under the inguinal ligament. Another method, which we prefer, consists of a microsurgical decompression and neurolysis, eliminating any compressive factor under the inguinal ligament. Surgeons must be aware of the anatomical variations that can be encountered in order to avoid surgical injury or not isolate the nerve. In the majority of cases, LFCN presents at the site of surgery as a single trunk, deep to the tight superficial fascia and to the inguinal ligament, and coursing inferior-lateral to the anterior superior iliac spine; less frequently there can be an early nerve bifurcation (37.8 %), an epifascial position (2.7 %), an inferior-medial direction (11.5 %), or an exit from the pelvis through an iliac bone canal (4.4 %) [5]. The surgical decompression can be performed through an infrainguinal skin incision that identifies the nerve distal to the inguinal ligament and follows it proximally or through a suprainguinal retroperitoneal approach, which permits an easier and more accurate recognition of the nerve trunk and direct access to the predilected sites of compression, the inguinal ligament, and the iliac fascia [1]. Recently Siu et al. [18] have reported their experience on the surgical treatment of 42 patients: decompression was achieved by freeing the nerve at three levels: (a) the tendinous arch from the iliac fascia, (b) the inguinal ligament anteriorly and a sling of fascia posteriorly, and (c) the deep fascia of the thigh along each division. Six weeks after surgery there was 43 % of complete relief, 40 % of partial relief, and 17 % of no relief; at a median follow-up of 4 years, complete relief was obtained in 73 % of patients, partial and no relief in 20 and 7 %, respectively [18].

36.4 Entrapment of the Common Peroneal Nerve

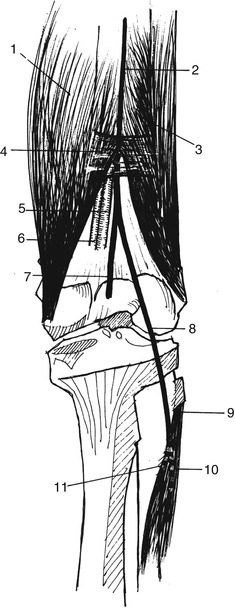

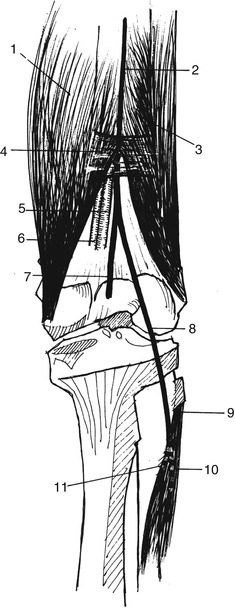

In the upper popliteal fossa, the sciatic nerve divides into two terminal branches, the peroneal and the tibial nerve. From its origin, the peroneal nerve diverges from the tibial nerve going downward and externally along the medial margin of the long head of the biceps femoris muscle and its tendon. Then, it passes laterally around the fibular head (the floor of the “fibular tunnel”) under the soleus and peroneus longus muscles (the roof of the “fibular tunnel”) entering the anterolateral aspect of the leg and dividing into two terminal branches, the deep and the superficial peroneal nerve (Fig. 36.3).

Fig. 36.3

Schematic drawing of the posterior aspect of the thigh to illustrate the sites of entrapment of the sciatic and peroneal nerves. 1 Great adductor muscle, 2 sciatic nerve, 3 biceps femoris, 4 fibrous band, 5, 6 popliteal artery and vein, 7 tibial nerve, 8 peroneal nerve, 9 long peroneal muscle insertion, 10 superficial peroneal nerve, 11 deep peroneal nerve

Common peroneal mononeuropathy involves more frequently men than women and is idiopathic in 16 % of cases, iatrogenic in 21.7 %, correlated to posture in 23.2 %, or after weight loss in 14.5 % due to external compression in 5.8 % or to artrogenic cyst at the fibula in 1.4 % of cases and posttraumatic in 10 % of cases [2]. It is also reported in bedridden patients in 7.3 % of cases [2].The common peroneal nerve may be compressed in the popliteal fossa by abnormal deposition of fatty tissue or by a Baker’s cyst. At the fibular head, superficiality and fixation to the bone by dense connective tissue render the nerve particularly vulnerable to pressure and traction. The most common cause of compression is the so-called crossed-leg palsy. A sudden and energic flexion and inversion of the foot is one of the most common mechanisms of injury. Deficit of the common peroneal nerve is expressed by (a) weakness/atrophy of the muscles located in the anterior compartment of the leg resulting in impaired foot flexion, with consequent foot drop or equine foot, and foot eversion, and (b) sensory impairment over the anterolateral aspect of the foreleg and the dorsum of the foot; pain is variable and less common. Clinical examination and electrophysiological and radiological studies of the popliteal fossa and the lumbar spine are useful to recognize the syndrome. In cases in which an external compressive factor is clearly recognized, a good recovery occurs spontaneously; in other instances operative exploration should be proposed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree