15 Personality disorders

Introduction

Normal personality may be used to refer to:

Personality disorder and mental illness

Introduction to personality disorders

Clinical features

Personality disorders have been classified by:

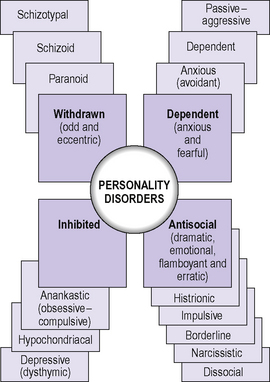

Research demonstrates considerable reliability between psychiatrists on an individual’s trait descriptions. However, there is much less reliability on an overall actual diagnostic category of personality disorder for an individual. In the UK, ICD-10 is used for official data collection. The types of personality disorders described, with their prominent traits, are shown in Table 15.1. Not all the features described for each personality disorder will necessarily be present; three are required as a minimum for diagnosis. In clinical practice there is often an overlap between diagnostic categories, but personality disorders do tend to cluster into three or four groups, as shown in Figure 15.1. These are:

Table 15.1 ICD-10 classification of personality disorders

| Personality disorder | Main characteristics |

|---|---|

| Paranoid | Oversensitivity, tendency to bear grudges, suspiciousness, misconstrues neutral or friendly actions of others as hostile or contemptuous |

| Schizoid | Emotional coldness, preference for fantasy, introspective reserve, little interest in having sexual experiences with others, lack of close, confiding relationships |

| Anxious (avoidant) | Pervasive tension and apprehension, self-consciousness, hypersensitivity to rejection, enters into relationships only if guaranteed uncritical acceptance |

| Exaggerates potential dangers and risks in everyday situations and avoids certain activities, leading to restricted lifestyle | |

| Dependent | Encourages or allows others to assume responsibility for major areas of individual’s life; subordinate to, compliant with and unwilling to make demands on those on whom they depend |

| Perceives self as helpless, fears being abandoned and alone, devastated when close relationships end | |

| Anankastic (obsessive–compulsive) | Indecisiveness, perfectionism, excessive conscientiousness, pedantry and conventionality, rigidity and stubbornness, plans all activities far ahead in immutable detail |

| Histrionic | Tendency to theatricality, overemotional, suggestible, shallow and labile affectivity, craves attention, manipulative |

| Emotionally unstable | |

| Impulsive type | Emotionally unstable, lack of impulse control, outbursts of violence or threatening behaviour common |

| Borderline type | Unclear or disturbed self-image, intense and unstable relationships, which may lead to repeated emotional crises that may be associated with a series of suicidal threats or acts of self-harm |

| Dissocial | Irresponsibility, cannot maintain relationships, low tolerance of frustration and low threshold for discharge of aggression, including violence |

| Incapacity to experience guilt and to profit from experience (including punishment), blames others or offers plausible rationalizations for antisocial behaviour |

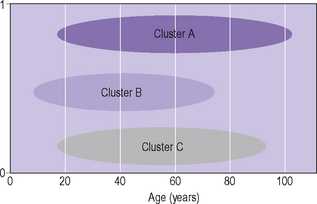

The differences in the onset and course of these three clusters are illustrated in Figure 15.2.

Figure 15.2 • Differences in onset and course of clusters of personality disorders.

(Reproduced with permission from Tyrer P 2010; see Further reading)

Withdrawn personality

Dependent personality

Antisocial personality

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree