CHAPTER 238 Piriformis Syndrome, Obturator Internus Syndrome, Pudendal Nerve Entrapment, and Other Pelvic Entrapments

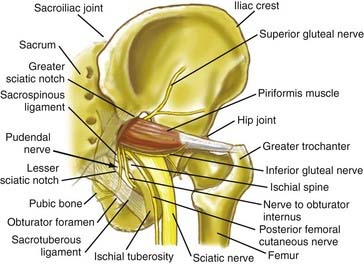

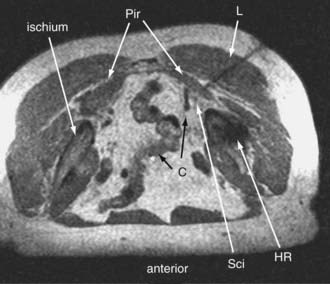

Pain in the upper buttock over the posterior superior iliac spine may also be due to entrapment of the superior cluneal nerves. Nonradiating pain in the mid buttock may be direct pain from the piriformis muscle or may be related to a trochanteric bursitis. Pain involving the piriformis muscle often includes associated radiating nerve pain such as sciatica because the sciatic nerve passes through the sciatic notch along with the piriformis muscle (Fig. 238-1).

Diagnosis and Management of Pelvic Sciatic Syndromes

Physical Examination Findings in Pelvic Sciatic Entrapment Syndromes

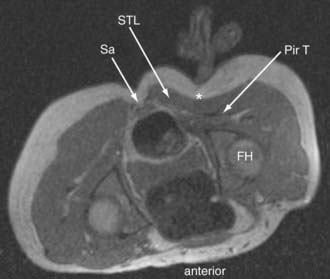

Sciatic entrapments at the sciatic notch often affect all five toes (multiple dermatomes) rather than just the lateral toes (S1 radiculopathy) or medial toes (L5 radiculopathy), which is most commonly seen in those with herniated lumbar disks. The pain of sciatic entrapment more commonly extends primarily only as far as the knee, ankle, or heel—not reaching the toes at all. Straight leg raising is generally negative, but resisted abduction or adduction of the flexed internally rotated thigh usually reproduces the symptoms. Sciatic notch tenderness is present in all patients with piriformis syndromes (Fig. 238-2), so other variant types of pelvic sciatic entrapment should be considered when this examination feature is not present. Trochanteric bursitis responsive to injection of the bursa occurred in 7% of patients diagnosed with muscle-based piriformis syndrome.

Neurography Results for Sciatica of Nondisk Origin

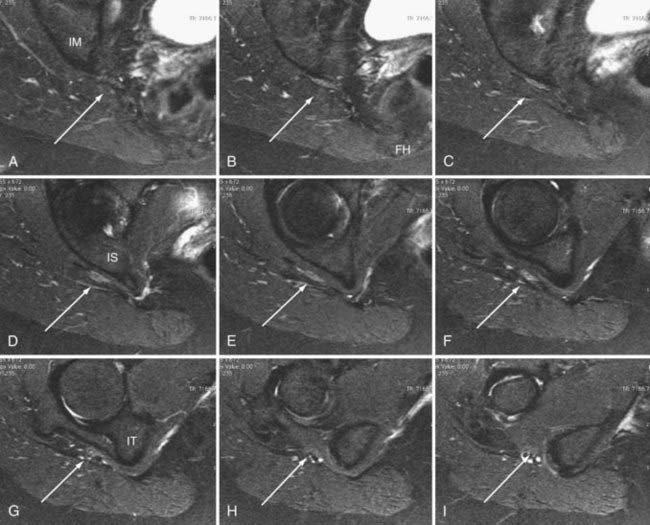

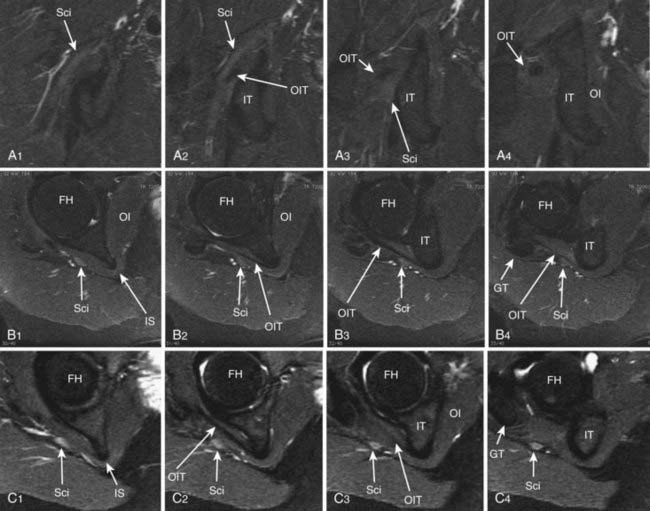

Until recently, objective tests for the existence of piriformis syndrome were very limited, there was no reliable effective treatment, and the pathophysiology was not well understood.1 Piriformis syndrome remains a subject of significant debate within the neurosurgical community.2,3 However, magnetic resonance neurography has proved helpful in providing objective diagnostic criteria.4 Figure 238-3 demonstrates the appearance of the sciatic nerve in a magnetic resonance neurography image in a typical pelvic sciatic entrapment case. Ipsilateral piriformis muscle hypertrophy is a common image finding in piriformis syndrome.5,6 Ipsilateral muscle atrophy occurs in some patients as well. Edema or hyperintensity in the ipsilateral sciatic nerve relative to the contralateral nerve occurs in 88%.4

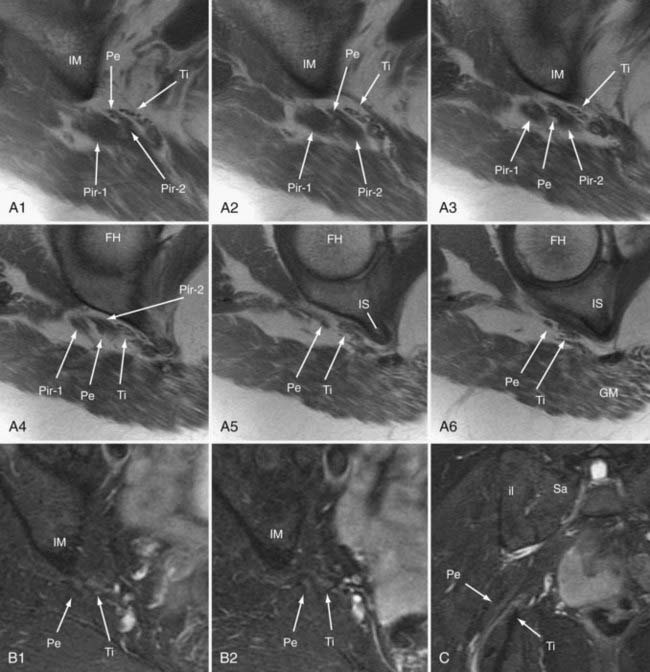

In addition to entrapment at the sciatic notch, the sciatic nerve may be compressed by fibrous bands and by dilated venous varices when the dilated vein arises inside the perineurial sheath. It may suffer entrapment owing to fixation by an artery passing through the nerve and by tendon or muscle passing through the nerve (Fig. 238-4). In some individuals, the sciatic nerve does not contact the tendon of the obturator internus, but in others, it may be entrapped by that tendon (Fig. 238-5). Entrapment also occurs in the lower ischial tunnel adjacent to the hamstring attachments or at the quadratus femoris muscle.

Open Magnetic Resonance Imaging–Guided Injections for Piriformis Syndrome

Because of the large volume of bupivacaine, procedures should be carried out in a surgicenter setting. The injection is monitored with fast (10 to 15 seconds) three-slice image sets—a working image and the two adjacent images slices. The needle advance must be maintained in the center slice of the three-slice set so that an accurate depiction of needle depth is seen. Because the piriformis muscle is often no more than 1 to 2 cm thick (Fig. 238-6), and because the bowel is often adjacent just deep to the muscle, it is necessary to reimage once or twice with each movement of the needle. Lower-accuracy alternatives to open MRI include x-ray fluoroscopy with the needle directed toward the space below the sacroiliac joint, computed tomography (CT) guidance, or electromyography with ultrasound.7

Minimal Access Surgery for Pelvic Entrapments of the Sciatic Nerve

Surgery is carried out generally on an outpatient basis using a 3-cm incision for a minimally invasive transgluteal approach with piriformis muscle resection, neuroplasty of the sciatic nerve and of the posterior femoral cutaneous nerve,8 and then placement of Seprafilm (Genzyme, Cambridge, MA) as an adhesiolytic agent. A similar approach is used for sciatic entrapments at the level of the ischial tuberosity.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree