6 CHAPTER CONTENTS COLLATING THE FINDINGS FROM THE ASSESSMENT PROCESS Needs, Skills and Occupational Performance Identifying Priorities and Negotiating Goals Strengthening the Goal-Setting Process Designing the Programme of Therapeutic Intervention The Occupational Therapist’s Skills Case Management and Care Coordination Building on Chapter 4 and Chapter 5, which focused on the assessment stage of the occupational therapy process, this chapter continues with the next stage of the process: planning and implementing interventions. The initial assessment has already been completed and the occupational therapist and service user are ready to identify the individual’s needs, skills and priorities in order to set goals for interventions (see Fig. 6-1). (It may be helpful to read this chapter in tandem with Chs 4 and 5.) Just as with the assessment process, the planning and implementation process involves ‘art and skill’. Occupational therapists adapt how they use their therapeutic skills with each individual; using theoretical knowledge, as well as their experience, when planning, implementing and evaluating interventions. Depending on the service user’s occupational needs, the occupational therapist encourages and motivates the service user to foster engagement using, for example, listening skills, therapeutic use of self, personal qualities and role modelling. FIGURE 6-1 The process for planning and implementing interventions. (Adapted from Creek and Bullock 2008, p. 110.) The occupational therapist identifies the service user’s needs by examining the findings of the assessment to gain a clear understanding of the problems the individual is experiencing. During the assessment process, service users are encouraged to look at their current and future situations. The service user is the one who knows how their mental illness impacts on their life, their abilities and difficulties and what has helped in the past. To analyse the assessment information, the occupational therapist organizes it into strengths, skills (positive aspects) and problems. By discussing the assessment results with the service user, the occupational therapist assists the service user to gain insight into their skills and limitations, which promotes self-discovery and respects their right to direct their own intervention. An individual will only require occupational therapy intervention if their occupational performance levels have changed due to mental illness. When an occupational therapist is working with a service user to identify their problems, it is best not to focus on their clinical diagnosis. The mental illness is only one aspect of a person, and they may, or may not, find their diagnostic label helpful. Knowing a diagnosis may mean the therapist ‘anticipates’ or sets inaccurate expectations of the likely problems relating to the diagnosis; adversely affecting the therapist’s ability to see the service user as an individual. Each person requires a range of skills in order to be able to perform their occupations. Lack of skills or insufficient competence in skills, can lead to the individual being unable to perform activities that will support them to take ownership of their recovery and achieve their personal goals. (There is further information about life skills in Ch. 19.) The occupational therapist uses the assessment findings to establish whether, or not, the individual has achieved an adequate level of competence and skills in the past. The individual’s current occupational skill level is determined to identify what skills they will need to learn, or re-gain, to help them to engage in self-care, productivity and leisure activities. The assessment highlights the skill areas that must be developed if the service user is to fulfil their occupations. Setting goals for achieving these skills is the next step in the intervention process. Complex problems can be analysed in different ways, using a variety of theoretical perspectives. For example, a service user who has a problem with establishing and sticking to a routine during the day and week could be viewed as having: ■ an occupational performance problem: coping with stress when doing new activities ■ an activity limitation issue: limited knowledge of local resources to support engagement in meaningful activities ■ a task performance problem: confidence to engage in new activities ■ a skills deficit: poor problem-solving skills. Once the therapist and the service user have agreed on how the problem(s) will be addressed, the occupational therapist will record what has been agreed and document the consent to treatment (see Chs 7 and 10 for information about record-keeping and consent, respectively). The occupational therapist negotiates with the service user to identify which problems they perceive to be the most important. The service user may avoid areas in their lives they feel are too hard or challenging to face. Using the rapport they have built with the service user, knowledge about their past, and present issues, the occupational therapist can use assertive communication skills to support the service user to prioritize the practical issues being experienced. Within the initial stages of therapy, it can be overwhelming for the service user to focus on all of their problems. The occupational therapist supports the individual to focus and facilitates their thinking by: ■ asking the service user what is important to them ■ exploring further how each problem affects their daily life ■ what their family and friends may see as the main problems ■ what they see as the main problem ■ what would make their current situation more positive; easier to function within and less stressful. The occupational therapist uses problem-solving skills and creative thinking to support the service user to break down the problems into smaller, more manageable problems to focus on initially. Through this process, the occupational therapist encourages the service user to focus on their skills, strengths and achievements, to make a balanced assessment of their abilities and problems. Occupational therapists need to support the individual to: ■ negotiate goals that are realistic and will meet their desired outcomes of intervention ■ focus on their recovery goals ■ develop an accurate picture of their occupational functioning. A goal is a written or spoken statement about particular achievements, plans or tasks that are to be achieved in the future. Setting goals enables the service user to move from vague ideas of what they want, to more concrete aims in order to effectively manage a problem, need or desire. The service user and the occupational therapist work collaboratively; the therapist may provide more support and input at the start. As the process develops, the service user will be encouraged and supported to take more responsibility. Lack of insight or unrealistic goals can be challenged by the therapist focusing on attainable goals and reinforcing the positive outcome that could be achieved. The therapist needs to ensure the goals do not overestimate the individual’s potential, as this could lead to frustration, or underestimating the individual, as this will limit the potential for skill development. Goals that are both challenging and achievable provide the service user with the opportunity to develop skills at a higher performance level. Goals are written with the service user, to guide the therapeutic process. Goals are written in language free of jargon, using the service user’s language, so they can understand the purpose of the therapeutic interventions. The SMART formulation, i.e. specific, measurable, attainable/achievable, relevant/realistic and timely, is often used to document goals (see Table 6-1). Goals are written in terms of ‘change statements’ and indicate timeframes in which they will be achieved. Having a timeframe helps the occupational therapist to monitor change and provides the service user with clear expectations on how they will reach the goal. If there is no timeframe, the service user may become bored or frustrated with therapy sessions and disengage. The service user and therapist monitor progress by assessing change and analysing the outcome of therapy sessions referring to the original goal. Goals are set according to what therapeutic interventions are achievable in the available time. Not all of the service users’ goals may be achievable within the timeframe. For example, when working with a service user experiencing an acute crisis, the timeframe will be short (i.e. days and at most weeks), compared with a service user with a severe mental illness, which could mean up to 3 years (or more) of occupational therapy intervention. Goals are usually set on two or three levels, i.e. long-term goals, intermediate goals and short-term goals. Given the importance of goal-setting, these are now discussed in more detail. Long-term goals are the overall goals of intervention and the service user is supported to look at long-term goals by focusing on future aspirations, dreams and personal life goals. When working with service users on their long-term goals, the expectation is for the service user to return to previous occupations and explore other activities that support social inclusion; restoring meaningful roles and responsibilities within their local community. The role of the therapist is to support and encourage the service user to work towards achieving their long-term goals, providing opportunities for personal growth, maintaining hope and positive expectations for the future. To assist the service user to find meaning in their life and a positive identity, long-term goals should be focused on the individual building a life beyond their illness, by having more control of their illness and life. The intervention phase is designed in-line with the service user’s long-term goals, which are part of a wider programme that may also involve other disciplines. Occupational therapy goals need to be shared with others involved in the service user’s care. Intermediate goals may be clusters of skills to be developed, attitudes to be changed or barriers to be overcome on the way to achieving the long-term goals of therapy. The timeframe for long-term goals may mean it would take several months or years for the service user to achieve the desired outcome. To help the service user to see that their hopes and aspirations are achievable, long-term goals are broken down to intermediate goals. Intermediate goals focus on several skills, such as motivation to engage in activity; developing meaningful routines and roles or modifying their social and physical environment. This allows the service user to gain an awareness of how long-term goals can be achieved. The smaller goals are steps towards the accomplishment of the longer-term goals and developing a sense of personal responsibility. An episode of an acute phase or relapse of a mental illness can impact on the ability of the service user to focus on their hopes and dreams for the future. The service user will be able to accept responsibility and control of their recovery if goals are based in the ‘here and now’. Intermediate goals might focus on engaging in meaningful activity, such as artwork three times during the week; going to their local gym twice a week; going out with a friend or writing in their reflective diary. Three main factors determine what the intermediate goals should be: 2. Any barriers to performance that need to be overcome, for example, motivation and anxiety in leaving their home environment to engage in daily activities 3. The advantages of learning skills in a developmental sequence so that higher-level skills are built on lower-level skills. Short-term goals are the small steps on the way to achieving long-term and intermediate goals. The short-term goal is usually to learn a sub-skill, or skill component, of the adaptive skill that is needed for successful occupational performance (Mosey 1986). Short-term goals are organized into sequence, with the most basic goal to be tackled first. Short-term goals are used to help individuals gain a sub-skill or skill component of an activity, to allow immediate gratification. This will support and focus the service user’s motivation on achieving intermediate and long-term goals. To encourage and support motivation during therapeutic intervention, short-term goals need to focus on skills that will be meaningful for the service user and have a positive outcome. The skill component chosen by the service user should be broken down into a sequence of smaller steps that meet the current level of occupational functioning of the individual, to ensure it is manageable and achievable. Short-term goals should be reviewed regularly and can be modified during any point of the process of intervention to meet the occupational needs of the service user. Once the short-term goals have been agreed, a programme of activities that will lead to their achievement is planned. Knowledge of activity analysis and synthesis enables the therapist to identify, or modify, activities to incorporate all the skills, personal factors and environmental factors that will best bring about change. The goal-setting process can be strengthened by supporting service users to: ■ increase their motivation and ongoing commitment by providing continued support through feedback after sessions ■ set goals that are activity related ■ maintain motivation by identifying improvements in occupational performance ■ regularly re-visit goals to make adjustments or changes to the goals according to their current occupational needs. Attach measures to the goal, so the service user and the therapist are able to determine when it has been reached. For example, a woman with severe anxiety and social phobia has the overall aim of feeling less anxious among other people. Her immediate goal is to be able to walk into a room with people in it and not to feel anxious. The performance marker she identifies will enable her to tell when the goal has been attained to a standard that is satisfactory for her. For her, the performance marker may be to be able to walk into a room and initiate a conversation with someone within the first 10 minutes. Once goals have been documented, the service user and occupational therapist continue to work collaboratively to develop an intervention plan. The responsibility is shared, so the individual can start taking ownership and control of their recovery. The aim of the intervention plan is to identify meaningful activities that will support and encourage the service user to re-engage in activities to help accomplish their goals. This can involve individual and/or group work and may involve carers, if the service user consents to this, and other professionals when appropriate. The skill of the therapist is to help the service users identify activities that are at the right level of challenge, to make it possible for them to succeed and reach their full potential. Activities can vary from simple to complex; for example meal preparation can vary from making a sandwich to planning, organizing and preparing a birthday meal for a family member. Within this process, the therapist will think about what skills are required during the performance of the activity, and how activities can be adapted to meet the skill level of the service user. This process is called ‘task analysis’ and it helps to identify the sequence of steps before carrying out a detailed activity analysis (this is discussed later in the chapter). The planning of interventions is not a linear process. It is an ongoing process of reassessment, evaluation of outcomes, discharge planning and reviewing and evaluating the overall programme; so it can be modified when necessary. It is essential to communicate with other team members and professionals involved in the service user’s care, to keep them informed of the purpose of the occupational therapy intervention and desired outcomes. Once the interventions have been agreed, they will be documented in the care plan, alongside the goals already documented, to articulate what will happen during therapy sessions. Activity as a form of therapeutic intervention is central to occupational therapy practice and is used to secure changes in occupational function (Finlay 2004). The intervention programme needs to be managed in partnership between the occupational therapist and the service user. Consideration should be given to the location and time of therapy sessions, and is negotiated between the service user, occupational therapist and other services involved. This takes into account: ■ When the service user feels more alert and confident ■ The impact of medication ■ When energy levels are higher ■ Fitting in around other daily routines and roles ■ Making sure it does not impact on other activities the service user engages in during the day or week ■ Time factors involved, such as setting up and preparing for the therapy session ■ Risk management, to reduce the chances of any untoward incidents, while still allowing for positive risk-taking. The intervention programme needs to be focused and led by the service user’s occupational needs and goals, and the format should be chosen accordingly. Group intervention is selected when the occupational therapist is able to identify other service users with similar occupational needs and goals. They must have all agreed they would like to engage in a therapeutic group session to achieve their goals. Negotiating with the individual about what activity they want to engage in, will allow positive choice and sustain engagement to encourage recovery to take place. Many factors influence the occupational therapist’s suggestions for the activity to be used in interventions, e.g. ■ motivation, interests, meaning of activity to service user ■ occupational needs ■ abilities and skills ■ service users’ values ■ what is personally or culturally important to the service user ■ how it relates to goals ■ how it relates to their environment and future life, e.g. recovery orientated ■ grading activity to current skill level, working on particular skills using/activity analysis and/or task analysis ■ the therapist’s knowledge and skills, and the activities that are available ■ pragmatic considerations – the possibility of leave being granted according to the Mental Health Act (2007); resources including budget constraints within the department; time, money the service user has available and staffing numbers. When the service user is unable to identify activities they would like to engage in to help achieve their goals, the therapist will need to be both imaginative and realistic when suggesting activity options. This may include: ■ past activities that have been of interest or allowed an experience of personal success ■ activities that have motivated or provided a sense of achievement ■ suggesting cultural activities ■ using the internet, or magazines, as an information sources ■ interest checklists ■ spiritual experiences, such as scripture, prayer, attending places of worship, accessing online religious resources or singing songs. The therapist will not always have the experience of, or skills in, a particular activity chosen by the individual. To ensure the activity is successful, the therapist may need to carry out further research or learning, to understand the skills and steps involved in the activity, to help with the activity analysis (this is discussed later in the chapter). Consideration of the service user’s environment is essential. Occupational therapists need to provide opportunities to engage in self-care, leisure and productive activities in the environment that best meets the service user’s needs to encourage a positive outcome. They also need to consider any environmental constraints related to where the activity will take place (in the service user’s home, local community or in hospital). Once this has been established, the next step is to explore what physical adaptations are needed; the type of room; seating; noise; light; how many people the space can accommodate and the social environment. By adjusting the physical environment, or creating the optimum social environment, the service user can be facilitated to achieve independence, safely. When using local non-mental health community facilities, which should be done as often as possible, any community environments selected for intervention need to be welcoming and make the service user feel valued. This helps to develop supportive social relationships and positive social links and networks, which aid in deceasing social isolation. Other factors that influence the extent to which someone engages in an activity are motivation, volition and autonomy. Motivation is ‘a drive that directs a person’s actions towards meeting needs’ (Creek 2010): it has been described as the energy source for action (du Toit 1974). Motivation can be extrinsic or intrinsic. Extrinsic motivation is ‘the drive to avoid harm and meet needs’ (Creek 2007) and intrinsic motivation is ‘the drive to act for the enjoyment of exercising one’s capacities, for learning and for taking pleasure in activity’ (Creek 2007). Everyone has motivation, or a drive to be active, but people choose to do different things. The capacity to make choices about what to do is called volition. Volition is ‘the action of consciously willing or resolving something; the making of a definite choice or decision regarding a course of action’ (New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary 1993). It has been defined for occupational therapists as ‘the skill of being able to perceive and work towards a goal through choosing and performing activities that will achieve desired results’ (Creek 2007). Some of the factors that affect people’s choices of action include: ■ Interests – the ‘individual’s preferences for occupations based on the experience of pleasure and satisfaction in participating in those activities’ (Kielhofner 1992, p. 157) ■ Personal goals – the results that the individual wants to achieve by his actions ■ Values – the individual’s ‘personally held judgement of what is valuable and important in life’ (Creek 2003, p. 60) ■ Awareness of own capacities – the ability to predict one’s own effectiveness in a given situation ■ Meanings – the significance or importance that an activity has for the person performing it (Creek 1998). These include the personal associations that it has for the individual and wider socio-cultural meanings ■ Nature of the choices available – this will depend on what the environment can offer but also on the individual’s ability to access an activity. For example, there may be a local cinema but a person cannot choose to watch a film if they do not have enough money ■ Knowledge of what activities are available – the individual can only choose activities that they are aware of ■ Knowledge of how to access different activities – it is not enough to know that an activity is available, the individual also has to know where it is, how to get there and the conditions for taking part ■ Capacity to see opportunities for action – some activities are not available all the time, so it may be necessary to know when they can be accessed. For example, it is usually necessary to enrol for adult education classes during a particular week of the year ■ Information on which to base choices – as can be seen from the last three points, a person needs information about what activities are available, how to access them and when they can be done. The therapist can create conditions for the service user to exercise volition by suggesting activities that have meaning and value for the service user, giving sufficient information about what is available and providing opportunities for them to practise making real choices. Even if someone is highly motivated and able to choose a course of action, there will be times when they are unable to do what they want due to circumstances. This can mean that their autonomy is compromised. Autonomy is ‘the capacity to think, decide, and act on the basis of such thought and decide freely and independently and without … hindrance’ (Gillon 1985/1986, p. 60). The ability to make and enact choices rests on three types of autonomy: ■ Autonomy of thought: being able to think for oneself, to have preferences and to make decisions ■ Autonomy of will: having the freedom to decide to do things on the basis of one’s deliberations ■ Autonomy of action: the capacity to act on the basis of reasoning. Autonomy is not an ‘all or nothing’ condition; different people have varying levels of autonomy and it can vary for the same person at different times. For example, when someone feels low in mood they can find it more difficult to think clearly or to make decisions. Conditions that may affect a person’s autonomy include personal circumstances, environmental barriers and social pressures (Creek 2007). Within the therapeutic environment, the therapist creates conditions that allow the service user to exercise autonomy. However, it is also important to identify barriers within the service user’s own environment and to help them find ways of addressing the barriers. There are many elements that can influence the outcome of an intervention, such as the service user, peer support, a focus on recovery, the occupational therapist’s skills, occupation-focused practice and case management. These need to be considered when planning and implementing interventions. At the start of occupational therapy intervention, the service user may take a passive role, and want or expect things to be done for them, while others flourish when they are given information, skills and support to manage their mental health and take responsibility for their own recovery process. The individual can be motivated by the occupational therapist not focusing on the service user’s illness and symptoms and helping them identify their strengths, dreams and instilling hope for the future. This can be achieved by the therapist supporting the service users to tell their story through the use of creative activities. Engaging in creative activities alongside the individual, the occupational therapist can use this encounter to develop a relationship, experience enjoyment and allow the opportunity for the service user to express their thoughts and feelings in a relaxed and comfortable environment. A service user referred to an occupational therapist within a mental health team may not have any previous experience of mental health services, or they may have been in contact with services for several months or years. Their past experience of mental health services may influence their expectations of what will be provided and what is expected of them. Service users with a long history of mental illness may have experienced more paternalistic approaches to their care, where mental health teams had lower expectations and assumed service users needed assistance and staff to ‘take control’. To overcome this challenge, the occupational therapy interventions will need to emphasize working alongside the service user, sharing responsibility and encouraging active engagement in their recovery. This will allow the service user to see how their personal recovery can be enhanced by them having more active control over their life. There are different ways in which this can be achieved, for example peer support and adopting a recovery focus. A peer support worker is someone who has lived experiences of mental health problems, who works alongside service users to help facilitate recovery through promoting hope and providing support based on common experiences. Employment of peer support workers in mental health services is rapidly growing in many countries such as the US, Australia, New Zealand and the UK. Peer support can range from informal peer support, service users participating in consumer- or peer-run programmes, and the employment of service users as peer support workers within traditional mental health services (Repper and Carter 2011). Peer support is founded on core values, such as empowerment; taking responsibility for one’s own recovery; the need to have opportunities for meaningful life choices, and valuing the lives of people with mental health problems as equals. Peer support encourages a wellness model that focuses on strengths, hope for the future at all stages of mental distress, and recovery, rather than an illness or medical model. Service users may feel more open to discussing their thoughts or behaviour with peer support workers rather than professionals. As service users may benefit from peer support (McLean et al. 2009; Repper and Carter 2011), this is something that occupational therapists should consider when planning interventions. Recovery is about discovering – or re-discovering – a sense of personal identity, separate from illness or disability (see Ch. 2). It should be an integral part of planning and implementing interventions. Accessing useful information, peer-led support groups, self-help groups and self-help tools (available as internet-based or hardcopy written resources) can help develop a service user’s confidence in negotiating choices and taking increasing personal responsibility through effective self-care, self-management and self-directed care. The service user can be encouraged to narrate their story and be supported in starting their own recovery plan, through using recovery planning tools. Examples of recovery tools that can help guide and support recovery are the Mental Health Recovery Star (http://www.mhpf.org.uk/programmes-and-projects/mental-health-and-recovery/recovery-star) or the Wellness Recovery Action Plan (WRAP) (www.mentalhealthrecovery.com). Family and other supporters are often crucial to recovery and they should be included as partners wherever possible, with the service user’s consent. The service user can be supported to move away from mental health services and access local community organizations to help them develop confidence, self-acceptance, self-esteem, reclaiming power and experience the feeling of belonging, cultural, social and community identity. Occupational therapists need to envisage recovery as a process rather than an end-point to promote the development of hope and optimism. They also need to acknowledge and work with people’s strengths, talents, interests, abilities, dreams, aspirations and limitations. To aid an individual’s recovery, the occupational therapist can assist in identifying meaningful goals and provide support to best manage their illness through engagement in meaningful activities. One of the areas the occupational therapist can focus on, when supporting the recovery of people with a mental illness, is reducing social isolation. This is done through activity-focused interventions that help move the service user in the direction of fuller participation in their local society, to increase social integration and social inclusion (Lloyd et al. 2008). Barriers to participation in activities that can impact on mental health recovery, can come from internal sources (lack of skills) and external sources (limited peer support, environment, negative social and cultural attitudes, lack of occupational choice and opportunity). Occupational therapists can take a lead role in decreasing exclusion and developing health and mutually beneficial partnerships with organizations in the wider community. This can break down the current barriers and for people with mental health problems to be recognized for their talents. The experience and skill of the therapist also influence which intervention techniques are used. When occupational therapists graduate, they have been taught basic skills and therapeutic interventions within a range of different services. The more skills the occupational therapist has in their repertoire and the more theories they are able to draw on, the better able they will be able to work in a person-centred way and respond to an individual’s needs and environmental demands. The stages involved in developing expertise were identified in a study by Benner (1984) (see Box 6-1). During the process of planning and implementing interventions some therapists will base their practice on their practical or technical skills, while others will use theory and models to direct their practice. With experience the therapist will begin to work in a non-linear way through each stage of the therapy process (Creek 2007). The occupational therapist will combine thinking about the situation, problem solving and analysing the activity, negotiating with service users and relevant others to decide what action needs to be taken.

Planning and Implementing Interventions

INTRODUCTION

COLLATING THE FINDINGS FROM THE ASSESSMENT PROCESS

Needs, Skills and Occupational Performance

Identifying Priorities and Negotiating Goals

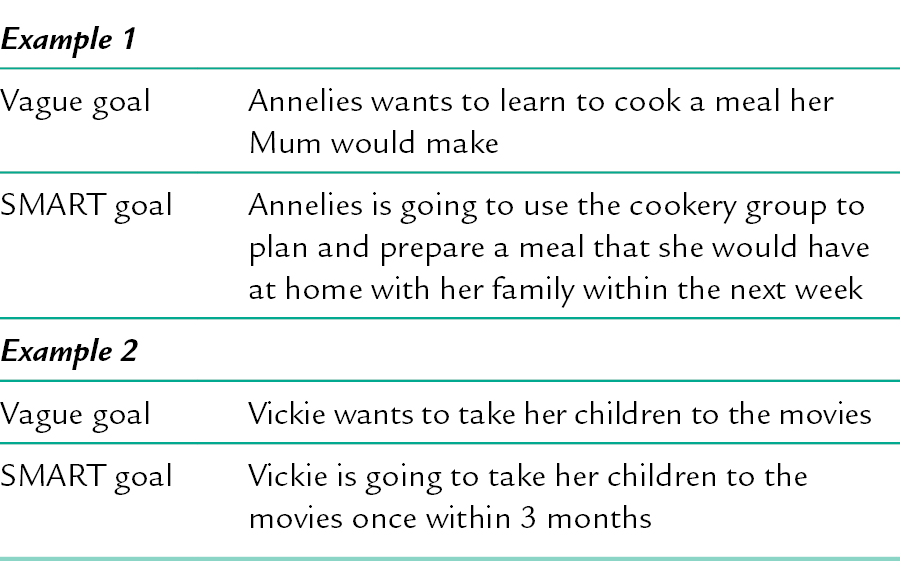

GOAL-SETTING

Documenting Goals

Long-Term Goals

Intermediate Goals

Short-Term Goals

Strengthening the Goal-Setting Process

PLANNING INTERVENTIONS

Designing the Programme of Therapeutic Intervention

Choice of Activity

Environment

Motivation (Creek and Bullock 2008, p. 119)

Volition (Creek and Bullock 2008, pp. 119–120)

Autonomy (Creek and Bullock 2008, p. 120)

CONTEXT OF THE INTERVENTION

Service User

Peer Support

Focus on Recovery

The Occupational Therapist’s Skills

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree