CHAPTER 279 Posterior Approach to Cervical Degenerative Disease

Surgical approaches for the management of degenerative disorders of the cervical spine, including herniated disk and spondylosis, may be broadly segregated into anterior and posterior approaches. Recent evidence-based guidelines have reported that there is insufficient evidence to recommend one surgical approach over another for the treatment of cervical spondylotic myelopathy (CSM).1 Although in many cases a clearly superior approach may not be evident, understanding the specific techniques and advantages and disadvantages of each will allow the surgeon to make informed, rational decisions.

On the negative side, however, posterior approaches are generally associated with greater postoperative neck pain than is the case with anterior surgery because of the more extensive muscular dissection required. Restoration of lordosis, particularly in an osteopenic patient, can be difficult from a solely posterior approach; anterior interbody support plus correction is often a more powerful technique if hypolordosis is a significant concern. The infection rate with posterior approaches is higher than that with anterior approaches.2 This is more reflective of an extremely low rate of infection with anterior cervical surgery than of a high rate with the former.

Imaging

The three most important factors in determining whether a posterior (dorsal) approach to cervical degenerative disease is appropriate or feasible are the location of the disease (dorsal or ventral), the extent of disease (number of spinal segments involved), and the alignment of the cervical spine (lordotic, straight, or kyphotic). Compression that is purely dorsal or dorsolateral is generally best relieved with surgery from a posterior approach. A common scenario involves a patient in the seventh or eighth decade with a thick, buckling ligamentum flavum causing multisegmental spinal cord compression. Occasionally, such a patient is initially seen after a fall with an acute neurological deficit (Fig. 279-1).

Pathology that extends over many cervical segments, particularly if it crosses into the thoracic spine, is often treated preferably via a posterior approach. Degenerative spinal disease superimposed on a congenitally narrow canal (<12 mm, identified on a lateral radiograph by near-superimposition of the posterior cortex of the lateral masses and the spinolaminar line) is one such situation. Another condition that often involves multiple segments at initial evaluation is ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL) (Fig. 279-2). The typically extensive, confluent disease seen with OPLL ossification is often optimally approached posteriorly, particularly because the ventral dura is frequently annealed to the ossified ligament and a spinal fluid leak is unavoidable if an anterior approach is used.

Indications for Surgical Treatment

Surgical treatment of cervical degenerative disorders, such as CSM or radiculopathy, may be indicated in patients with progressive signs of myelopathy, progressive or severe weakness in a cervical myotome, or intractable radicular pain and correlative imaging. The natural history of CSM is variable and unpredictable for any particular patient.3 Recommendations may be tailored to the patient based on age, symptoms, and findings on electromyography (EMG) or radiography, among other factors.4 Once progression has been demonstrated, however, it is unlikely that the process will halt completely or reverse spontaneously.5 In these circumstances, a frank, clear discussion should be held with the patient and family regarding the potential risks associated with surgical intervention versus the risks associated with continued observation.

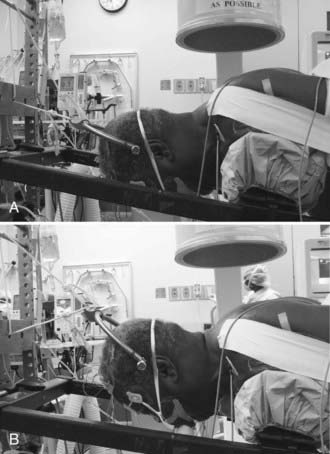

Anesthesia and Positioning

We use the prone position exclusively for posterior cervical surgery. Based on surgeon preference, either an electric operating table with padded bolsters and a rigid Mayfield head holder or a Jackson spine table with Gardner-Wells traction is used. With the Jackson table, a bivector traction setup with two ropes is used to permit the patient to be positioned initially in relative cervical flexion to facilitate the decompressive portion of the procedure and placement of the fixation points. The weight is moved to the upper rope to enhance cervical lordosis before placement of the rods and performing the arthrodesis (Fig. 279-3). A horseshoe head holder is placed 2 to 3 cm away from the patient’s face to serve as a backup should a problem occur with the traction.

Spinal Cord Monitoring

Although we routinely monitor SSEPs and MEPs in these patients, the utility of this strategy and the appropriate response to changes in signal quality, amplitude, or latency in different clinical scenarios are sometimes unclear. We have, on occasion, identified problems with positioning of the arms and shoulders based on monitoring changes. During decompression of a stenotic foramen it is not unusual to see transient nerve root irritation on free-running EMG that has no apparent clinical postoperative correlation. An evidence-based review found conflicting data regarding the use of intraoperative improvements in electrophysiologic data for clinical prognostication.6

Foraminotomy/Diskectomy

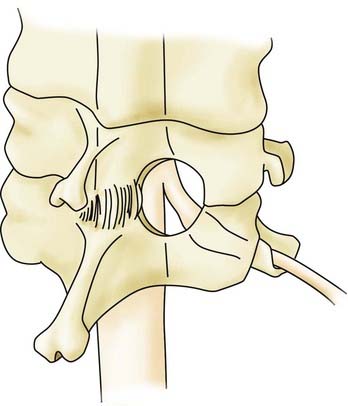

The posterior keyhole foraminotomy as first described by Scoville has a role in the treatment of isolated foraminal stenosis or lateral disk herniation.7 Patients with symptoms referable to a single cervical nerve root are the best candidates for this procedure. Bone removal is tailored to the nature of the pathology. In patients with spondylosis and osteophytic foraminal stenosis, a keyhole-shaped decompression extending from the lateral thecal sac to the lateral border of the pedicle is performed to achieve complete decompression of the exiting nerve root. For the removal of lateral soft herniated disks, a smaller amount of bone can be removed to preserve the majority of the facet joint.

A herniated cervical disk impinges on the exiting nerve root that corresponds to the pedicle caudal to the disk space (e.g., a C5-6 herniated disk causes C6 impingement). The foraminotomy is performed at the appropriate interspace just proximal to the pedicle of the level caudal to the disk herniation (Fig. 279-4). The first part of the foraminotomy procedure consists of a small laminotomy and flavectomy to expose the lateral dura and the origin of the exiting nerve root. The foraminotomy is extended laterally by using a high-speed drill to thin the ventromedial superior facet. Bone removal is completed with small straight and up-going curets. A minimal amount of the inferior facet is removed. After the axilla of the exiting nerve root is identified and a portion of the root approximately 2 to 3 mm in length is exposed, a micro–nerve hook is used to dissect parallel with the nerve root along its caudal edge. With removal of less than half the facet joint, up to 5 mm of the nerve root may be exposed.8 The pedicle is palpated, the nerve hook is then rotated ventral to the root, and the disk herniation is identified. A microdissector or micro–nerve hook may be used to place gentle retraction on the nerve root to expose the disk fragment, which is removed with micro–pituitary rongeurs. Complete decompression of the nerve root is confirmed with passage of the micro–nerve hook through the foramen dorsal and ventral to the nerve root. During the dissection or after the decompression, hemostasis of the epidural veins is accomplished with thrombin-soaked collagen in either a patty (Gelfoam, Pharmacia & Upjohn, New York) or semiliquid (FloSeal, Baxter, Deerfield, IL) formulation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree