13 Problems of emotion and motivation

At the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

1. explain the difficulty of defining the concept of ‘emotion’

2. discuss the importance of having a working knowledge of emotional difficulties in people with a neurological condition

3. discuss the main theories related to depressive disorders and detail the mechanism of action of the major classes of anti-depressant medication

4. describe the most common emotional problems in people with stroke, traumatic brain injury (TBI), Parkinson’s disease (PD) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD)

5. outline the basic principles of our current understanding of the relationship between the brain and emotion

6. explain how neurological, psychological and social factors may account for emotional difficulties in people with neurological conditions

7. explain the potential impact of emotional problems on a patient’s rehabilitation outcomes and quality of life.

Introduction

Many neurological conditions in which the brain is affected are associated with changes in emotion, mood and motivation (Cappa 2001). For many patients and their families, the emotional ‘fallout’ of a neurological condition may be one of the most difficult problems they have to cope with. Health professionals working with patients who experience emotional distress may also find this to be challenging.

Emotion: an overview

Emotion: can it be defined?

• Physiological (i.e. involving the endocrine, nervous and musculoskeletal systems)

• Psychological (i.e. thoughts, beliefs, expectations)

• Behavioural (i.e. expressed through voice, posture and movement).

Some psychologists have made attempts to define emotion. Here is an example by Smith (1993):

When we think of an emotion, we may be inclined to think that this is unique to each of us – specific to our own individual world of experience only. Although it is attractive to indulge in the notion of a strictly private world, ground-breaking work by Darwin in the 1850s confirmed that there are around six basic facial expressions, each conveying a distinct emotion, which are understood the world over (Darwin 1865, cited in Berthoz 2003). These universal facial expressions communicate:

Pioneering work by anthropologist Ekman in Papua New Guinea, where until that time no Westerner had set foot, confirmed these basic emotions; when told an emotionally charged story and asked to express what this felt like, local inhabitants showed facial expressions that could readily be understood by people from Western civilisations (Ekman 1984).

Depression

• a persistent sad or ‘empty’ mood

• a loss of interest in what were previously pleasurable activities

• alterations in sleeping and eating patterns

Causes of depression

Current biomedical views on the cause of depression centre round the monoamine hypothesis, which was first proposed in 1965 by Schildkraut. This hypothesis puts forward the idea that depression occurs as a consequence of abnormalities in the levels of the monoamine neurotransmitters (noradrenaline [NA], serotonin [5-HT]) in the limbic system. As mentioned in Chapter 2, the limbic system is the ‘emotional part’ of the brain and this system will be described more in detail below. Research points to particular evidence that reduced serotonergic neurotransmission is involved. It is hypothesised that depression is caused, in part, by a number of biochemical/pharmacological changes within the limbic system.

There are a number of key pieces of evidence that both support and refute the monoamine theory.

Evidence against the monoamine theory

Having stated that other systems may be involved in the neuropharmacology of depression, it cannot be denied that some of the main, active anti-depressant drugs do indeed exert their therapeutic effect through the manipulation of monoamine systems. Some examples of drugs that work via monoamine systems are discussed below, although for a full list of all of the mechanistic approaches you should refer to one of the pharmacology texts suggested at the end of Chapter 4.

Treatment of depression

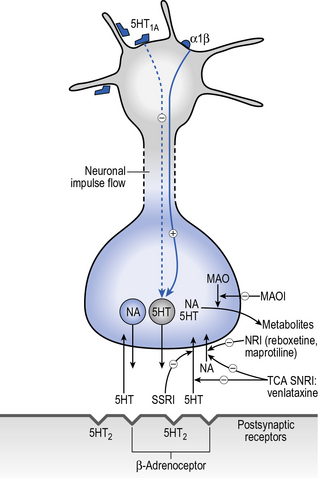

The mechanisms of action of the antidepressants covered next can be seen in Figure 13.1. This diagram shows a single synapse containing both NA and 5-HT, although in reality there would be either a noradrenergic synapse or a serotonergic synapse.

Fig. 13.1 • The mechanism of action of some antidepressants.

(Based on Waller et al 2001, with permission)