Chapter 19 Prolactinomas

Prolactinomas are the most common type of functioning pituitary tumors, accounting for approximately 50% to 60% of functioning pituitary adenomas.1,2 These prolactin-secreting adenomas are the second most common type of pituitary tumor overall after nonfunctioning adenomas and represent 30% to 40% of all pituitary tumors.3,4 Their prevalence is generally thought to be up to 100 cases per 1 million people,5 and one meta-analysis of the literature estimated a much higher prevalence rate of approximately 17% of the population, with a third of tumors staining positive for prolactin.6

The objectives for treatment of hyperprolactinemia due to prolactinomas are normalization of the hyperprolactinemic state, preservation of residual pituitary function, reduction of tumor mass, and prevention of disease recurrence. Pharmacologic therapy with dopamine agonists remains the mainstay of treatment;7–10 however, surgical removal of prolactinomas remains an important treatment in those patients who cannot tolerate or are resistant to medical therapy. Surgery may play a curative role in some cases of microprolactinomas.1,11,12 The current surgical management strategies for patients with prolactinoma are discussed in this chapter.

Clinical Presentation

Patients with prolactinomas can present with clinical manifestations of hyperprolactinemia, endocrine dysfunction, local mass effect, or pituitary apoplexy (Table 19-1). The biologic effects of hyperprolactinemia predominantly affect the gonadal axis and breast tissue. The primary effects of prolactin are to stimulate lactation, but this hormone can also promote deleterious effects on the gonadal axis. Excessive prolactin centrally inhibits hypothalamic production of gonadotropin-releasing hormone and subsequently inhibits secretion of luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone, resulting in infertility and hypogonadism.13,14 Clinical presentation appears to differ between males and females.

Table 19-1 Clinical Manifestations of Prolactinomas

| Hyperprolactinemia |

| Amenorrhea (females) |

| Galactorrhea (females) |

| Gonadal dysfunction |

| Infertility |

| Decreased libido |

| Impotence (males) |

| Osteoporosis |

| Delayed puberty (adolescents) |

| Mass Effect |

| Headaches |

| Visual acuity and field loss |

| Diplopia |

| Ophthalmoplegia |

| Facial numbness |

| Facial pain |

| Hypothalamic impairment |

| Hydrocephalus |

| Hypopituitarism |

| Pituitary apoplexy |

In premenopausal women, the most common presentation includes galactorrhea, amenorrhea, and infertility. Although prolactinomas are equally distributed at autopsy, women are four times more likely to develop symptoms than men. Because of these readily identifiable symptoms, women generally present earlier in the course of the disease and have smaller tumors at the time of diagnosis. Hyperprolactinemia may not be detected until after discontinuation of an oral contraceptive.15 Approximately 5% of women with primary amenorrhea and 25% of women with secondary amenorrhea (excluding pregnancy) are found to have a prolactinoma,16 and this incidence rises to 70% to 80% when galactorrhea accompanies amenorrhea.17 Galactorrhea is present in 50% to 80% of women with hyperprolactinemia.18–20 In men harboring prolactinomas, hypogonadal manifestations of decreased libido and impotence are often attributed to aging or functional causes rather than hyperprolactinemia, delaying detection until the tumor becomes large (mostly macroprolactinomas) and causes local mass effect on neighboring structures. Compression on the optic chiasm, cavernous sinus, and pituitary gland can result in symptoms of visual loss (visual acuity and/or visual field loss), cranial nerve dysfunction resulting in ophthalmoplegia, and/or hypopituitarism, respectively.21 Galactorrhea and gynecomastia are extremely rare in men. About 2% of all men with impotence have a prolactinoma.16 Low testosterone levels can result from either hyperprolactinemia or hypopituitarism secondary to mass effect on the normal pituitary gland.

In young individuals, prolactinomas are the most common type of pituitary adenoma overall, particularly in adolescents older than 12 years of age.22,23 Prolactinomas are more common in girls and present with primary amenorrhea. Boys tend to have much larger tumors and higher preoperative prolactin levels than girls. They can also present with gynecomastia and hypogonadism and tend to have neurologic signs of mass effect.23 Growth retardation and short stature can be common presentations because growth hormone is the first hormone to undergo hyposecretion in pituitary adenomas.22 The signs and symptoms of hypogonadism in prepubescent children and post-menopausal patients, however, are clinically absent.24–26 Adolescent children can present with delay or failure of sexual/reproductive development.21,27–30

Persistent gonadal dysfunction resulting in estrogen or testosterone deficiency from prolonged hyperprolactinemia that is left untreated can result in premature osteoporosis in patients of either sex.17,31–34 These important but often overlooked effects of hyperprolactinemia are additional arguments for treating patients who may not be concerned about sexual dysfunction or fertility. Hyperprolactinemia-induced osteopenia is progressive and correlates with the duration of hypogonadism.35 If treatment is undertaken, normalization of hyperprolactinemia can impede further bone loss; however, although bone density increases to a certain extent, it may not necessarily return to normal baseline values.33,36–38

Tumor compression on neighboring structures can result in symptoms from mass effect such as visual acuity and visual field deficits; cranial nerve palsies resulting in diplopia, ophthalmoplegia, and facial numbness; or impedance of cerebrospinal fluid flow resulting in obstructive hydrocephalus. Compression of the normal pituitary gland can result in hypopituitarism, namely hypocortisolism and hypothyroidism. Pituitary apoplexy from an acute hemorrhage and/or infarction into a prolactinoma can cause rapid enlargement of the tumor, resulting in hypopituitarism and acute compression of the sellar and parasellar structures.39,40

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of a prolactin-secreting adenoma is determined by elevation of serum prolactin with radiographic evidence of a pituitary adenoma on magnetic resonance (MR) imaging of the pituitary region with and without gadolinium enhancement.41 Interpreting serum prolactin levels in conjunction with radiographic findings is important in making the correct diagnosis of a prolactinoma to ensure proper treatment. Serum prolactin levels generally correlate with tumor size: Levels from 100 to 250 ng/ml often signal a microprolactinoma (<10 mm), whereas levels greater than 250 ng/ml generally reflect a macroprolactinoma (>10 mm).4,42 Extremely elevated serum prolactin levels that are greater than 1000 ng/ml may correlate with a macroprolactinoma that has invaded the cavernous sinus. Macroadenomas associated with a mildly elevated prolactin level, roughly 50 to 125 ng/ml, can be attributed to the stalk-section effect from a nonfunctioning pituitary adenoma. This is because prolactin is under tonic inhibition from the hypothalamus, and lesions or compression of the pituitary stalk may interfere with this inhibition, resulting in mild elevation of prolactin. However, it is important to rule out the “hook effect” in cases of giant and invasive macroprolactinomas in which the serum prolactin level is falsely low (25 to 150 ng/ml). This is due to excessive serum prolactin saturating the binding sites of the two-site (monoclonal “sandwich”) technique resulting in falsely normal levels of prolactin. Subsequent dilutional testing of prolactin samples can counteract this assay phenomenon and prevent incorrect diagnosis.43–46

The diagnosis of prolactinoma requires that other causes of hyperprolactinemic states (either physiologic or pathologic) and other mass lesions in the sellar and parasellar region are ruled out (Table 19-2).13,14,42 Most cases of hyperprolactinemia can be ruled out on the basis of the history and physical examination, a pregnancy test, and thyroid and renal function tests. MR imaging with gadolinium enhancement should then be obtained to confirm the diagnosis of a prolactinoma. Other pituitary-related serum hormone levels (growth hormone, insulin-like growth factor-1, fasting AM cortisol, adrenocorticotrophic hormone, luteinizing hormone, follicular stimulating hormone, sex hormones, and thyroid function tests) can be used to test anterior pituitary function in all patients with a radiographically confirmed pituitary adenoma.

Table 19-2 Etiology of Hyperprolactinemia

| Physiologic |

| Exercise |

| Stress |

| Pregnancy |

| Breast feeding (suckling reflex) |

| Pharmacologic |

| Antidepressants (tricyclic, MAO inhibitors, SSRIs) |

| Antihypertensives (a-methyldopa, reserpine, verapamil) |

| Neuroleptics (phenothiazines, haloperidol) |

| Metoclopramide |

| H-2 blockers |

| Sellar/Parasellar Lesions |

| Prolactinomas |

| Nonfunctioning pituitary macroadenomas with “stalk effect” |

| Craniopharyngiomas |

| Rathke cleft cysts |

| Meningiomas |

| Germinomas |

| Sarcoidosis |

| Lymphocytic hypophysitis |

| Histiocytosis X |

| Metastasis |

| Primary empty sella syndrome |

| Other Disease States |

| Ectopic secretion of prolactin |

| Primary hypothyroidism |

| Hypothalamic dysfunction |

| Chronic renal failure |

| Cirrhosis |

| Chest wall lesions (trauma, surgery, herpes zoster) |

| Seizures |

Medical Treatment

The primary goals of treatment for prolactinomas are to normalize hyperprolactinemia and its clinical sequelae, restore fertility, relieve tumor mass effect, preserve residual pituitary function, and prevent disease recurrence or progression.41 For smaller tumors, such as microprolactinomas (tumors <10 mm), removal of tumor mass is less concerning since these are usually not large enough to produce symptoms related to mass effect. Studies have demonstrated a lack of tumor growth in the vast majority of patients with microprolactinomas, which may remain unchanged throughout the patient’s life.47–49 Thus, in a patient with a microprolactinoma with only mild elevation of prolactin who has normal anterior pituitary function and no desire for pregnancy, observation can be a reasonable option.4

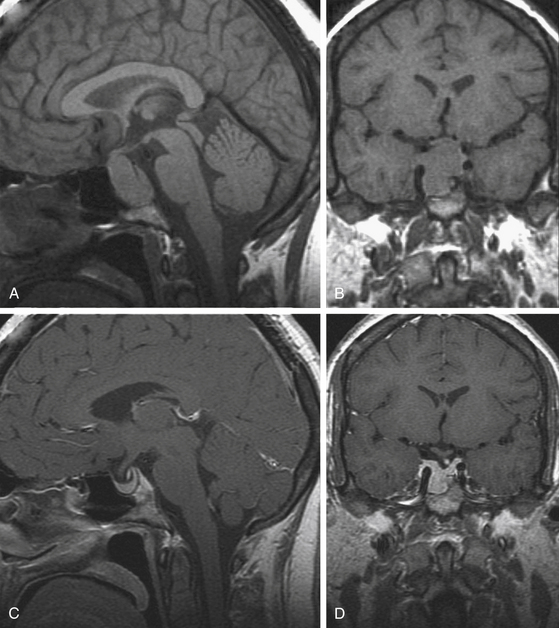

The first-line of treatment for prolactinomas is pharmacological intervention with dopamine receptor agonists, which bind to D2 receptors on lactotrophs to inhibit prolactin synthesis and release and reduce tumor volume.50,51 The agents that are currently approved for use in the United States are bromocriptine and cabergoline. Bromocriptine is very effective in normalizing prolactin levels in more than 90% of patients, significant reducing tumor mass in approximately 85% of patients,7,52–54 and restoring gonadal and anterior pituitary functions in over 80% of patients. Most female patients resume menstruation within 6 months of initiating therapy. Tumor shrinkage can occur rapidly within several days, decompressing the visual apparatus in patients with macroprolactinomas who present with visual deficits (Fig. 19-1).16,52,55 About 5% to 10% of patients may not be able to tolerate side effects of bromocriptine, including dizziness, nausea, arrhythmias, gastrointestinal discomfort, and orthostatic hypotension. About 10% to 25% patients are partially or totally resistant to bromocriptine.56–58

More recently, cabergoline has become the preferred first-line agent.59 Cabergoline is associated with less frequent and less severe side effects and is easier to administer than bromocriptine, although it is more expensive.60 In one study, cabergoline normalized serum prolactin in 84% of bromocriptine-intolerant patients and in 70% of bromocriptine-resistant patients.61 Cabergoline has been shown to be more effective in shrinking macroprolactinomas in naive patients than in patients pretreated with other dopamine agonists.62

After normalization of serum prolactin levels has been sustained for at least 2 years with adequate reduction and stabilization of tumor size, dopamine agonist therapy can be tapered to lower doses that continue to control hyperprolactinemia and tumor growth. In general, dopamine agonist therapy must be continued for life, and cessation of therapy usually results in recurrent hyperprolactinemia and tumor enlargement.63–65 However, in one study, Colao et al.5 reported sustained normalization of prolactin levels in 69% of patients with microprolactinomas and in 64% of macroprolactinomas without evidence of new tumor growth. Although there was no evidence of tumor recurrence in the face of recurrent hyperprolactinemia, the follow-up was relatively short and probably insufficient to detect delayed tumor recurrence.66 Given the above data, we currently continue all patients on cabergoline for 2 to 3 years. If there is documentation of tumor disappearance and normalization of prolactin levels, we will discontinue medication and monitor the patient with twice-yearly review of prolactin levels and annual MR imaging scans. Recurrence detected by increasing prolactin levels would then indicate the need for repeat treatment with dopamine agonists.

It should be emphasized that primary resistance to dopamine agonist therapy occurs in 10% to 15% of prolactinomas67 and secondary resistance may also rarely occur.68 Thus, all patients treated with dopamine agonists should undergo serial prolactin measurements and yearly MR imaging surveillance studies.

In patients desiring pregnancy, bromocriptine is the drug of choice because of its safety record.69,70 The experience with cabergoline is more limited, and it is not used as a primary therapy for infertility, although some reports state that it does not increase the risk of teratogenesis.71,72 Once menses is restored, normal conception and pregnancy may follow. If a menstrual cycle has been missed, a pregnancy test should be obtained and bromocriptine or cabergoline use should be discontinued immediately.18 If the patient develops symptomatic tumor enlargement during pregnancy, bromocriptine can be safely initiated (Fig. 19-1).73–76 There does not appear to be an increased risk of congenital anomalies or spontaneous abortions with use of bromocriptine in this manner.77 Alternatively, surgical debulking compression may also be an option if the patient does not respond to medical therapy. Patients with pre-existing macroprolactinomas tend to have a higher risk of symptomatic tumor enlargement (15%–35%)77 than those with microprolactinomas (0.5%–1%).3,55

Surgical Treatment

Indications

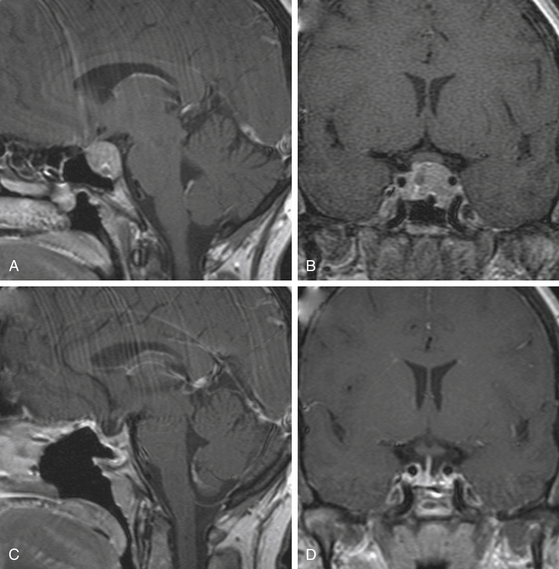

The efficacy and success of dopamine agonist therapy has limited the indications of surgical therapy for prolactinomas. Furthermore, surgery is rarely curative in patients with macroprolactinomas and so should be reserved for patients who cannot tolerate the side effects of dopamine agonists or for whom medical therapy is ineffective (those with persistent hyperprolactinemia, progressive tumor enlargement, and persistent tumor mass effect despite maximal medical therapy) (Fig. 19-2).11,78–80 Surgery may also be an option for treatment of microprolactinomas in patients who do not wish or cannot afford to be on life-long medical therapy (Fig. 19-3).1,12,66,81,82 For patients whose tumors are more likely to be cured surgically (microprolactinomas or tumors with preoperative prolactin <200 ng/ml) and who desire fertility, surgery can be considered to limit the need for long-term medical therapy, and in some instances may be less costly.66 Surgery may also be indicated in patients who are dependent on anti-psychotic medications, because dopamine agonists can precipitate psychotic episodes.83 Surgical resection should also be considered if impaired visual function or cranial nerve palsies are not immediately responsive to medical treatment, especially in cases of pituitary apoplexy, and in patients who present with a spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid leak after tumor shrinkage with dopamine agonist therapy.4

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree