18 Proximal Median Neuropathy

Detailed Anatomy at the Antecubital Fossa

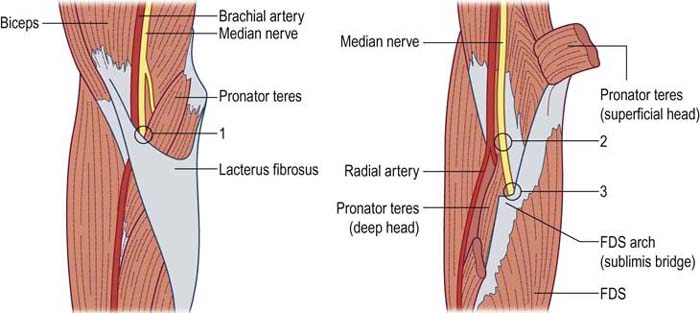

As the median nerve descends in the upper arm, it runs medial to the humerus and anterior to the medial epicondyle. In a minority of individuals, a bony spur originates from the shaft of the medial humerus just cephalad to the medial epicondyle. A tendinous band known as the ligament of Struthers stretches between the spur and the medial humeral epicondyle. In the antecubital fossa, the median nerve travels adjacent to the brachial artery (Figure 18–1). As it enters the forearm, it runs first beneath the lacertus fibrosus, a thick fibrous band that runs from the medial aspect of the biceps tendon to the proximal forearm flexor musculature. In most individuals, the median nerve then runs between the two heads of the pronator teres (PT) muscle to provide innervation to that muscle. In many individuals, there are fibrous bands within the two heads of the PT muscle. The anterior interosseous nerve then is given off posteriorly, approximately 5 to 8 cm distal to the medial epicondyle, after the median nerve passes between the two heads of the PT. As the median nerve runs distally, it passes deep to the flexor digitorum sublimis (FDS) muscle and its proximal aponeurotic tendinous edge, known as the sublimis bridge.

Etiology

In addition, several sites of proximal median entrapment have been reported (Figure 18–1). All are uncommon, and some remain controversial. The four major potential sites of entrapment are as follows:

• Median nerve entrapment may occur at the ligament of Struthers in the distal upper arm, where both the median nerve and brachial artery pass between this ligament and the humerus.

• More distally in the region of the antecubital fossa, the median nerve may become entrapped beneath a hypertrophied lacertus fibrosus.

• Further distally, the median nerve may become entrapped in the substance of the PT muscle, especially in individuals who have additional fibrous bands running through that muscle.

• More distally, the median nerve may become entrapped beneath the sublimis bridge of the FDS muscle.

Traumatic Lesions

In patients with traumatic lesions, there usually is an obvious, acute disturbance of median motor and sensory function. Significantly, sensory disturbance in proximal median neuropathy is noted in the entire median territory, including the thenar eminence, as well as the thumb, index, middle, and lateral ring fingers. This feature clearly distinguishes proximal median neuropathy from carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS), in which sensation over the thenar eminence is spared. Sensory loss over the thenar eminence occurs as the palmar cutaneous branch, which innervates the thenar eminence, leaves the median nerve proximal to the carpal tunnel. Depending on the site of the lesion, weakness may affect some or all of the proximal median-innervated forearm muscles, including the PT, FDS, flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) to digits 2 and 3, flexor carpi radialis (FCR), flexor pollicis longus (FPL), and pronator quadratus (PQ), as well as the distal median-innervated muscles, including the abductor pollicis brevis (APB), opponens pollicis (OP), and first and second lumbricals. Weakness of the FDP to digits 2 and 3, FDS and FPL often leads to a characteristic high median neuropathy posture, whereby the individual is unable to flex the thumb, index, and middle fingers (Figure 18–2).

Entrapment Syndromes

The symptoms and signs in the proximal median nerve entrapment syndromes are fairly nonspecific. Typically, there is pain or discomfort in the region of the entrapment. Unlike CTS, the symptoms are not exacerbated at night. The two major syndromes include (1) proximal entrapment of the median nerve at the ligament of Struthers and (2) median nerve entrapment more distally, either beneath the lacertus fibrosus, in the substance of the PT, or beneath the sublimis bridge (Figure 18–1). The latter three entrapment sites usually are referred to collectively as the pronator syndrome. Strictly speaking, the term may be reserved for nerve entrapment within the substance of the PT muscle proper. However, entrapment at any of these last three locations usually produces a similar clinical syndrome.

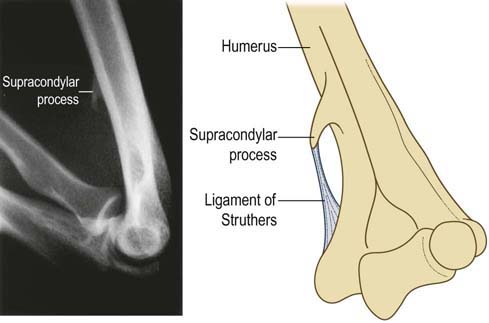

Ligament of Struthers Entrapment

Entrapment at the ligament of Struthers is a very rare syndrome whereby the median nerve is entrapped by a tendinous band running from the medial epicondyle to a bony spur on the distal medial humerus (Figure 18–3). The prevalence of such a supracondylar bony spur is approximated at 1 to 2% of the population. The syndrome is characterized by pain in the volar forearm and paresthesias in the median-innervated digits, which are exacerbated by supination of the forearm and extension of the elbow. The radial pulse also may be attenuated with these maneuvers, as the brachial artery also runs with the median nerve under the ligament of Struthers. A bony spur may be palpable at the distal humerus. Weakness of the PT and other median-innervated muscles may occur, and subtle sensory loss may be noted in the median distribution, including the thenar eminence.

Pronator Syndrome

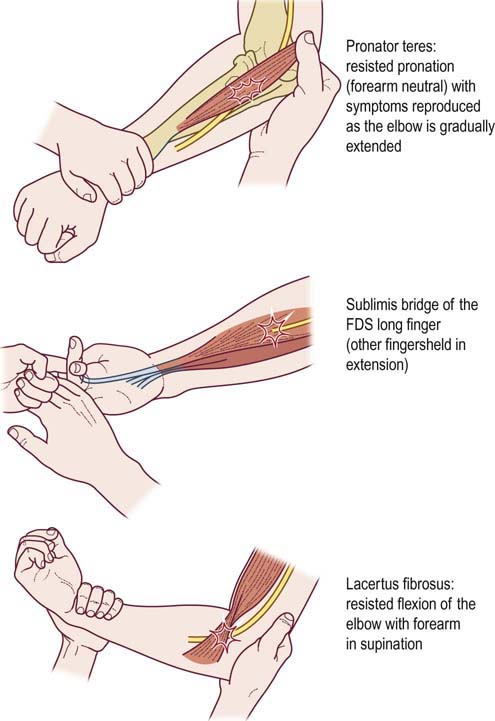

Although rare, the pronator syndrome occurs more often than entrapment at the ligament of Struthers. The PT muscle may be enlarged or firm, with a Tinel’s sign over the site of entrapment. Pain may radiate proximally and often is aggravated by using the arm, especially with repeated pronation/supination movements. Specific maneuvers that may produce symptoms of pain in the forearm and paresthesias in the median-innervated digits depend on the site of entrapment (Figure 18–4): resisted pronation with the elbow in extension (for the PT); resisted flexion of the proximal interphalangeal joint of the middle finger (for the sublimis bridge); and resisted flexion of the elbow with the forearm in supination (for the lacertus fibrosus). The sole finding of increased pain with these maneuvers is an unreliable sign, unless it is accompanied by median nerve territory paresthesias. Significant weakness or wasting of median-innervated muscles is rare, but mild weakness of the FPL and APB is not uncommon, with occasional involvement of the FDP to digits 2 and 3 and the OP. The pronator teres muscle is usually spared. There may be occasional paresthesias radiating into the median-innervated digits, with subtle impairment of sensation in the median nerve distribution, including the thenar eminence.

Anterior Interosseous Nerve Syndrome

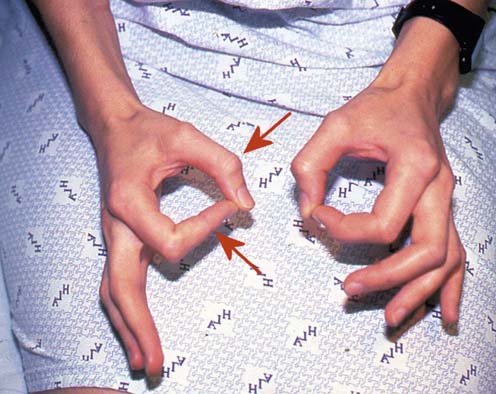

The anterior interosseous nerve, the largest branch of the median nerve, leaves the main trunk of the median nerve just distal to the PT to innervate three muscles: FPL, FDP to digits 2 and 3, and PQ. It carries deep sensory fibers to the wrist and interosseous membrane, but it carries no cutaneous sensory fibers. Clinically, patients present with the inability to flex the distal phalanx of the thumb, index, and middle fingers, with weakness of pronation. Weakness of the PQ is best demonstrated with the elbow flexed to avoid the contribution of the PT, which is not involved in anterior interosseous syndrome. With the elbow flexed, the PQ is the primary muscle to pronate the arm; with the elbow extended, the PT is the primary muscle to pronate the arm. There is no sensory loss. A characteristic compensatory posture occurs when the patient attempts to make an “OK” sign and is unable to flex the distal thumb and index fingers. Compensatory hyperextension of the distal interphalangeal joint of the index finger and interphalangeal joint of the thumb then occurs (Figure 18–5). Anterior interosseous neuropathy (AIN) has been reported to occur following fractures and crush injuries. In addition, it can rarely occur as an entrapment neuropathy, but more often it is a variant presentation of brachial neuritis, a full discussion of which is found in the section on brachial neuritis in Chapter 30, including the electrophysiologic evaluation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree