17 Psychiatry of disability

Definitions

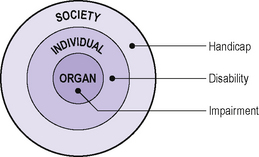

Figure 17.1 • Definitions of impairment, disability and handicap according to biopsychosocial level.

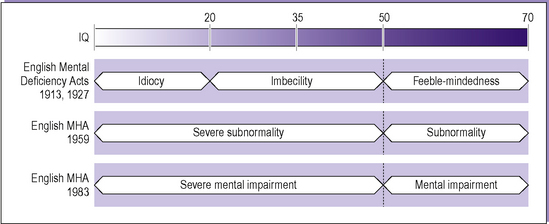

Many terms were used in the 20th century to describe people with learning disabilities. As each set of terms has been imbued with stigma and negative connotations a new set has been introduced, in the hope that attitudes towards such people will be more positive as a result, thus lessening the potential for handicap. The use of terms in successive UK mental health legislation illustrates this (Figure 17.2), as does the alteration in WHO labels. Different cultures also currently use different terms. A search of the literature for ‘learning disability’ (current UK term) would need to use ‘mental retardation’ or ‘developmental disability’ in the USA, or ‘mental handicap’ in other Western countries. In the USA, ‘learning disability’ encompasses ‘specific developmental delays’ (F81 – see Table 17.2).

Table 17.1 ICD-10 and DSM-IV-TR classifications: (F70–79 and 317–319) Mental retardation

| F70 Mild mental retardation (DSM-IV 317) |

| IQ range 50–69 |

| Delayed understanding and use of language |

| Possible difficulties in gaining independence |

| Work in practical occupations |

| Any behavioural, social and emotional difficulties are similar to the ‘normal’ |

| F71 Moderate mental retardation (DSM-IV 318.0) |

| IQ range 35–49 |

| Varying profiles of abilities |

| Language use and development variable (may be absent) |

| Often associated with epilepsy, neurological and other disability |

| Delay in achievement of self-care |

| Simple practical work |

| Independent living rarely achieved |

| F72 Severe mental retardation (DSM-IV 318.1) |

| IQ range 20–34 |

| More marked motor impairment than F71 often found |

| Achievements lower end of F71 |

| F73 Profound mental retardation (DSM-IV 318.2) |

| Severe limitation in ability to understand or comply with requests or instructions |

| IQ difficult to measure but <20 |

| Little or no self-care |

| Mostly severe mobility restriction |

| Basic or simple tasks may be acquired (e.g. sorting and matching) |

| Mental retardation, severity unspecified (DSM-IV 319) |

| In ICD-10 a fourth character may be used to specify extent of associated behavioural impairment: |

| F7×.0 No, or minimal, impairment of behaviour |

| F7×.1 Significant impairment of behaviour requiring attention or treatment |

| F7×.8 Other impairments of behaviour |

| F7×.9 Without mention of impairment of behaviour |

In ICD-10, child and adolescent psychiatric disorders may be classified multiaxially with the above designated Axis Three: Intellectual level in DSM-IV mental retardation is coded in Axis Two with personality disorder (if present).

In ICD-10, the categories F70–79 cover ‘mental retardation’ (Table 17.1). Whether a behaviour difficulty is also present can be specified for each level of disability. It must also be noted that, where possible, the syndrome or organic aetiology for the mental retardation should also be coded (e.g. Q90 Down’s syndrome). Labels such as those in section F70–79 are rarely very useful in individual clinical practice, as there can be wide variations in presentation within any particular IQ range. Assumptions about functioning made because of such labelling can be handicapping to an extent that exceeds the effect of an individual’s impairment. In addition, a multiplicity of relatively small impairments in a number of functional areas may result in considerable disability and handicap. Although there may statistically be an increased risk of other impairments (such as sensory impairments and mobility problems) with increasing ‘retardation’, this is only an association. It is particularly important in assessment to consider the whole person and his or her environment.

Table 17.2 ICD-10 classification: F80–89 Disorders of psychological development

| F80 Specific developmental disorders of speech and language |

| F80.0 Specific speech articulation disorder |

| F80.1 Expressive language disorder |

| F80.2 Receptive language disorder |

| F80.3 Acquired aphasia with epilepsy (Landau–Kleffner syndrome) |

| F80.8 Other developmental disorders of speech and language |

| F80.9 Developmental disorder of speech and language, unspecified |

| F81 Specific developmental disorders of scholastic skills |

| F81.0 Specific reading disorder |

| F81.1 Specific spelling disorder |

| F81.2 Specific disorder of arithmetical skills |

| F81.3 Mixed disorder of scholastic skills |

| F81.8 Other developmental disorders of scholastic skills |

| F81.9 Developmental disorder of scholastic skills, unspecified |

| F82 Specific developmental disorder of motor function |

| F83 Mixed specific developmental disorders |

| F84 Pervasive developmental disorders |

| F84.0 Childhood autism |

| F84.1 Atypical autism |

| F84.2 Rett’s syndrome |

| F84.3 Other childhood disintegrative disorder |

| F84.4 Overactive disorder associated with mental retardation and stereotyped movements |

| F84.5 Asperger’s syndrome |

| F84.8 Other pervasive developmental disorders |

| F84.9 Pervasive developmental disorder, unspecified |

| F88 Other disorder of psychological development |

| F89 Unspecified disorder of psychological development |

Also included in ICD-10 is a section on ‘Disorders of psychological development’ (F80–89; Table 17.2). These disorders have in common:

Epidemiology

This section can be divided into:

Impairment and disability

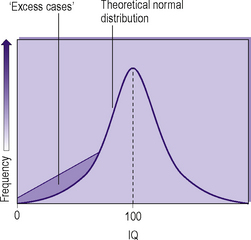

When IQ is used to define those with learning disabilities (LD), the assumption of normal variation in the population does not entirely determine the prevalence found, i.e. if one defines LD as an IQ of less than 70, the prevalence is 2.2% whereas the actual prevalence is 3.7% (Figure 17.3). For severe LD (IQ<50), the prevalence is approximately 0.4%. The skew to the left in Figure 17.3 is due to a combination of ‘statistical’ low IQ with those individuals with genetic/chromosomal abnormalities. Those with an IQ between 50 and 70 rarely have an obvious cause for their impairment, whereas individuals with an IQ below 50 frequently do have a more obvious aetiology such as a genetic abnormality.

There is a high correlation between different impairments (see Figure 17.5). A third of children with cerebral palsy are also found to have severe LD (but conversely this means that two-thirds are above this IQ level). A study of residential hospital admissions showed that 38% of those with severe LD also had cerebral palsy (with the majority having spastic paralysis of all four limbs). This latter figure must be viewed with caution, as the likelihood of hospital admission was increased by greater disability, even when the emphasis was not on care in the community. When children with LD were admitted to residential hospital, a third of the hospital population were found also to have epilepsy. Although the same reservations about a hospital population as above must apply, similar figures have been found in Swedish community studies (Table 17.3).

Table 17.3 Levels of coexistence of different impairments

| Severe mental retardation (%) | Mild mental retardation (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Cerebral palsy | App. 20 | App. 8 |

| Epilepsy | 30–37 | 12–18 |

| Hydrocephalus | 5–6 | 2 |

| Severe visual impairment | 6–10 | 1–9 |

| Severe hearing impairment | 3–15 | 2–7 |

| One or more major impairments | 40–52 | 24–30 |

Specific syndromes

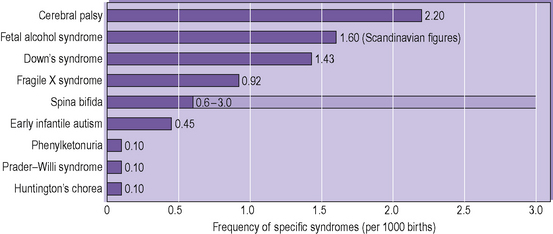

The frequencies of a number of the more common or well-known conditions are shown in Figure 17.4.

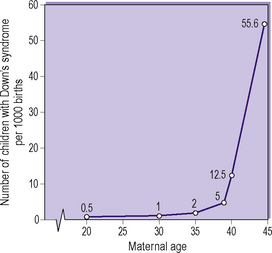

For Down’s syndrome there is a clear correlation between affected births and increasing maternal age (Figure 17.5). It must be noted, however, that the majority of children with Down’s syndrome are not born to women over the age of 35, despite the risk being so much greater. The figures for cytogenetic analysis of amniotic fluid at 15–16 weeks’ gestation show an even higher incidence of trisomy 21 than shown in Figure 17.5, suggesting a significant fetal loss rate.

Psychiatric and psychological aspects of disability

Corbett studied learning-disabled adults in Camberwell, south London, and found a prevalence of schizophrenia of 3.5%. This is very similar to the figures for hospital populations of adults with learning disabilities. He also found a further 3% with a previous history of schizophrenia. In the same study, he diagnosed 25% of the learning-disabled group as suffering from ‘personality disorder’ of varying types (see Chapter 15 for a discussion of the issues relating to such diagnoses). In a study of adults over the age of 50 with LD, 11.4% were found to be suffering from a psychiatric disorder, and 11.4% from dementia (combined figure 21%.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree