Psychiatry of the elderly

Epidemiology of psychiatric disorders in the elderly

Principles and practice of old age psychiatry

Clinical features and treatment of psychiatric disorders in the elderly

Introduction

Older people with mental health problems present particular challenges to the practice of old age psychiatry and the organization of its services. They are often physically as well as mentally frail, and this affects presentation and course. On the other hand, they have the advantage of a rich history to tell and a lifetime’s experience of responding to fortune and adversity. Dementia comprises a substantial part of the clinical practice.

When considering psychiatric disorder in the elderly, the clinician must be able to collect and integrate information from a variety of sources, and produce a management plan which takes account of physical and social needs, as well as psychological ones. This plan is likely to involve the cooperation of several professionals. It is in this clinical complexity that much of the challenge and fascination of old age psychiatry lies.

This chapter deals with the psychiatry of old age, with two important exceptions, both of which were covered in Chapter 13:

• delirium (see pp. 317–19)

• the clinical features, aetiology, and investigation of dementia (see pp. 321–35).

Normal ageing

Demographics

In 1993, 6% of the world’s population was over 65 years of age. However, in the more developed countries the proportion was about 14%, while in less developed countries it was 4%. Less developed countries have higher birth rates, but the life expectancy at birth is substantially lower than in developed countries—60 years, compared with 73 years. In the UK, life expectancy at birth has increased from 41 years in 1840 to 46 years in 1900, 69 years in 1950, and 80 years in 2011.

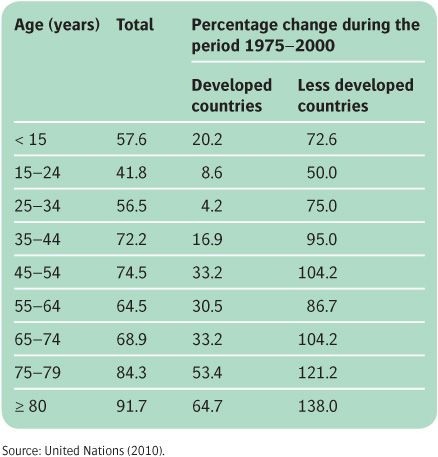

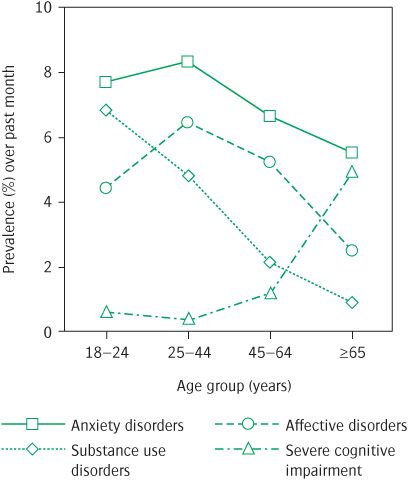

Table 18.1 shows that the difference in age structure of the population is changing, and Table 18.2 shows that the proportion of older people in less developed countries is increasing much faster than it is in developed countries. Although some psychiatric disorders become less common (see Figure 18.1), the prevalence of dementia increases rapidly with age (see below), and all countries face the increasing problem of managing large numbers of cognitively impaired older people.

Table 18.1 Percentage change in the world population during the period 1975–2000

Physical changes in the brain

The weight of the human brain decreases by approximately 5% between the ages of 30 and 70 years, by a further 5% by the age of 80 years, and by another 10–20% by the age of 90 years. As well as these changes, the ventricles enlarge and the meninges thicken. MRI studies show a complex temporal and spatial profile of changes affecting both grey and white matter, with volume reductions prominent in the hippocampus, frontal cortex, and cerebellum (Caserta et al., 2009).

Figure 18.1 Prevalence of mental disorders across age groups: data are 1-month prevalence rates from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study using DSM-III criteria. From Jorm (2000).

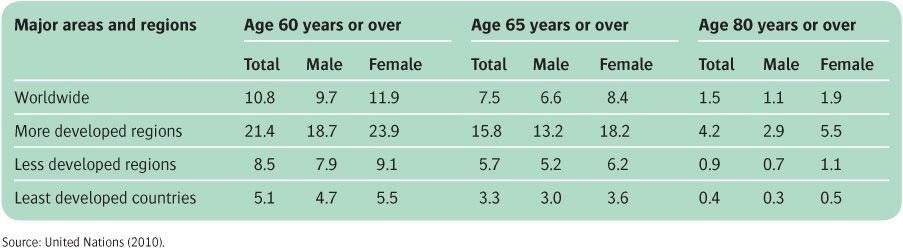

Table 18.2 Percentage of the population aged 60 years or over, 65 years or over, and 80 years or over by gender

There is some loss of neurons, although this is regionally selective and much less marked than was formerly believed, and reductions in synapses and dendrites appear to be more important. The cytoplasm of some neurons contains a pigment, lipofuscin. The ageing brain also tends to accumulate senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, but with a more restricted distribution and smaller numbers than in Alzheimer’s disease (see Chapter 13). Neurofibrillary tangles are usually limited to neurons in the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex, while senile plaques can also occur in the neocortex and amygdala. Similarly, a small proportion of brains from healthy old people contain Lewy bodies. For reviews of the neuropathology of normal ageing, see Hof and Morrison (2004) and Yankner et al. (2008).

Ageing itself is thought to reflect genomic changes (e.g. acquired damage to DNA or its epigenetic regulation), mitochondrial damage (due in part to disorders of calcium regulation and to free radicals), and alterations in some growth factor and signalling pathways, together with the accumulation of multiple random (stochastic) changes. For a review of the biology of ageing, see Bittles (2009).

The neuropsychology of ageing

Assessment of cognitive function in the elderly is complicated by the frequent presence of physical ill health, notably sensory deficits, and by the need to carefully distinguish normality from the earliest phase of dementia.

Longitudinal studies suggest that intellectual function, as measured by standard intelligence tests, shows a significant decline only in later old age. A characteristic pattern of change occurs, with psychomotor slowing and impairment in the manipulation of new information. By contrast, tests of well-rehearsed skills such as verbal comprehension show little or no age-related decline.

Short-term memory, as measured by the digit span test, for example, does not change in the normal elderly. Tests of working memory show a gradual decrease in capacity, so that the elderly perform significantly less well than the young if attention has to be divided between two tasks or if the material has to be processed additionally in some way. The elderly can usually recall remote events of personal significance with great clarity. Despite this, their long-term memory for other remote events shows a decline. Overall, there appears to be a balance between losses in flexible problem solving, and the benefits of accumulated wisdom derived from experience. For a review, see Anderson (2008).

As well as these cognitive and motor changes, there are alterations in personality and attitudes, such as increasing cautiousness and rigidity.

Physical health

In addition to a general decline in functional capacity and adaptability with ageing, chronic degenerative conditions are common. As a result, the elderly consult their family doctors frequently and occupy around 50% of all hospital beds. These demands are particularly large in those aged over 75 years. Medical management is made more difficult by the presence of more than one disorder, the consequent increased risk of side-effects of treatment, and by psychiatric and social problems.

Sensory and motor disabilities are frequent among elderly people. In a study of people over 80 years of age in Jerusalem, 50–60% reported problems with vision, hearing, or walking, and 22% had difficulties in talking (Davies and Fleishman, 1981). These figures are representative of those reported in other countries.

Social circumstances

For most people, ageing brings with it profound changes in social circumstances. Retirement affects not only income but also social status, time available for leisure, and social contacts. Loss of income is a serious problem facing many elderly people, and financial problems were the commonest worry reported in a large European survey of people over 65 years of age.

Social isolation is a fact of life for many older people, especially in developed countries. In the UK and the USA, about one-third of those over 65 years of age were living alone in 1993, compared with 7% in Chile and 3% in China. The figure in the UK increased markedly in the second half of the last century (by contrast, in 1851 it was 7%, and in 1921 it was 11%). However, for many older people, living alone is not seen as a problem and is aided by slowly increasing pensioner incomes and greater availability of suitable housing. Many older people see family, friends, and neighbours regularly, and provide as much support as they receive. In a European Commission survey in 1993, 44% of older Europeans saw a relative every day. This figure was highest in southern Europe and lowest in northern Europe, but, interestingly, reported loneliness showed the same pattern, being highest in countries with the highest levels of family contact.

Table 18.3 Percentages of people living alone, or in residential care, in England and Wales in 2001

Table 18.3 summarizes data from the 2001 Great Britain Census (www.statistics.gov.uk/cci/) on the proportion of elderly people who live at home alone, or who live in a ‘communal establishment’ (i.e. residential care or long-stay hospital bed). In both sets of statistics, women predominate, reflecting the greater number of widows than widowers (and thus women who lack a partner to care for them), and the higher level of disability reported by women than men at any given age. Note also that the lower row indicates that 93% of elderly people, including 67% of those over 85 years of age, live in their own home rather than in residential care, contrary to popular belief.

Epidemiology of psychiatric disorders in the elderly

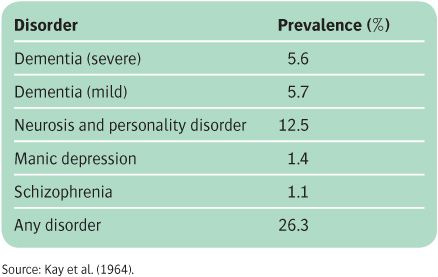

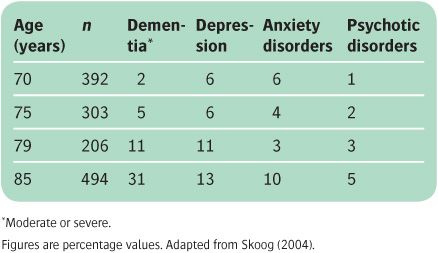

Kay et al. (1964) conducted the first systematic prevalence study of psychiatric disorder among elderly people in the general population, including those living at home as well as those living in institutions, in an area of Newcastle upon Tyne, in northern England. The findings (see Table 18.4) have been broadly replicated in subsequent surveys, taking into account changes in diagnostic criteria (e.g. inclusion of depression in their category of neurosis), and the problems of case finding. For example, a large French population study of people aged 65 years or over found a point prevalence of 14% for anxiety disorder, 11% for phobia, 3% for major depression, and 1.7% for psychosis, using an interview to make DSM-IV diagnoses (Ritchie et al., 2004). These figures mask the significant changes in the prevalence and proportions of disorders at different stages of old age, as shown by a large Swedish study (Skoog, 2004), summarized in Table 18.5.

Other surveys have shown a high prevalence of psychiatric disorder among elderly people in sheltered accommodation and in hospital. One-third of the residents in old people’s homes have significant cognitive impairment. In general hospital wards, between one-third and half of the patients aged 65 years or over have some form of psychiatric illness.

Table 18.4 Prevalence of psychiatric disorder in people over 65 years of age

Table 18.5 Changing prevalence of psychiatric disorders with age among the elderly

It has frequently been reported that general practitioners are unaware of many of the psychiatric problems among elderly people living in the community. Moreover, the presentation of such disorders to general practitioners and psychiatrists is determined as much by social factors as by a change in the patient’s mental state. For example, there may be a sudden alteration in the patient’s environment, such as illness of a relative, or a bereavement. Sometimes an increasingly exhausted or frustrated family decides that they can no longer continue to care for an old person.

As in younger people, there are gender differences in the prevalence, presentation, and course of some psychiatric disorders, and in treatment needs (Lehmann, 2003).

For a review of the epidemiology of psychiatric disorders in the elderly, see Henderson and Fratiglioni (2009).

Dementia

Although there are references in classical literature, dementia in the elderly has been recognized by modern medicine since the French psychiatrist Jean-Étienne Esquirol described démence sénile in 1838. Esquirol’s description was in general terms, but it can be recognized as similar to the present-day concept (Alexander, 1972). Emil Kraepelin distinguished dementia from psychoses due to other organic causes such as neurosyphilis, and he divided it into presenile, senile, and arteriosclerotic forms. In an important study, Roth (1955) showed that dementia in the elderly differed from affective disorders and paranoid disorders in its poorer prognosis.

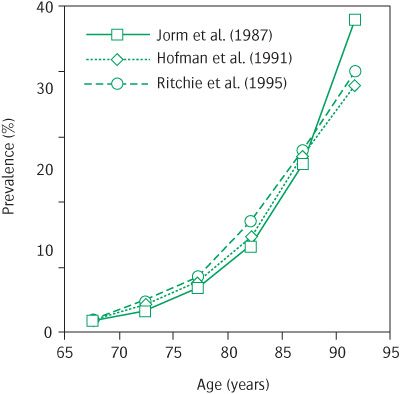

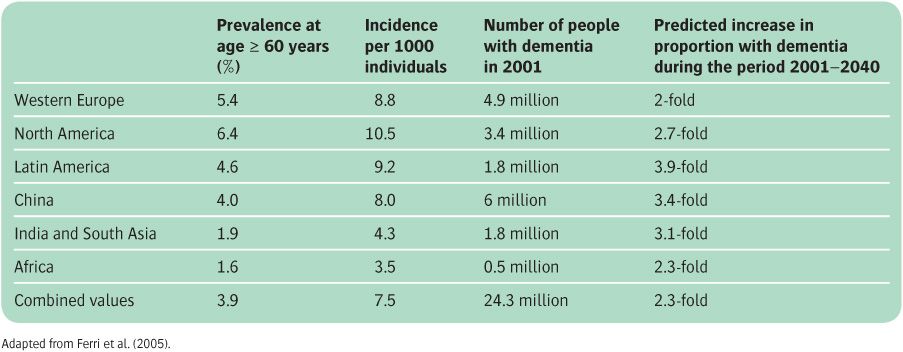

Following Roth (1955), there has been extensive research on the prevalence of dementia, and several meta-analyses (see Figure 18.2 and Table 18.6). For a review, see Ferri et al. (2005) and Reitz et al. (2011). Prevalence rises steeply with age, up to the age of 90 years, and thereafter the increase slows, and about 25% of centenarians remain cognitively intact. As discussed in Chapter 13, the commonest causes are Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, and dementia with Lewy bodies, with frequent coexistence of the features of more than one disorder.

Delirium

Delirium and its many causes were discussed in Chapter 13. Age is also a major risk factor. For example, in the community, rates of delirium rise from 1–2% to at least 14% in those over 85 years of age (Rahkonen et al., 2001). Elderly patients in hospital are at particular risk, with about one-third experiencing an episode of delirium (see Chapter 13).

Mood disorder

Despite the focus on dementia in the elderly, depressive disorders are considerably more common. A systematic review of community-based studies found an average prevalence of clinically relevant depression of 13.5% for those aged 55 years or over, of which 9.8% was classed as minor and 1.8% as major. Prevalence was higher in women and among older people living in adverse circumstances (Beekman et al., 1999). Consistent with these data, a large European collaborative study found rates of 8.5–14% for clinically significant depression in the elderly and 1–4% for major depression (Copeland et al., 1999). The figures show that a high proportion of depressed elderly people do not meet the criteria for major depression, but are instead variously labelled as having minor depression, dysthymia, or subthreshold depression. However, this does not diminish its clinical significance, as these cases have a similar morbidity and course to those of patients who meet the criteria for major depression (Beekman et al., 2002).

Figure 18.2 Prevalence rates for dementia across age groups: data from three meta-analyses. Reproduced from A. R. Lingford-Hughes, S. Welch, D. J. Nutt, Journal of Psychopharmacology, 18 (3), Evidence-Based Guidelines for the Pharmacological Management of Substance Misuse, Addiction and Comorbidity: Recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology, pp. 293–335, copyright © 2004 by (Sage Publications). Reprinted by Permission of SAGE.

Table 18.6 Prevalence and incidence of dementia in different populations

Rates of depression depend on the setting. Koenig and Blazer (1992) reported rates of 0.4–1.4% in the community, 5–10% among medical outpatients, 10–15% among medical inpatients, and 15–20% among nursing home patients. These variations probably reflect the frequent comorbidity of depression in the elderly with other psychiatric (Devanand, 2002) and physical (Krishnan et al., 2002) disorders. For example, rates of depression are higher in those with cardiac problems and neurodegenerative disorders, and one-third of patients have an alcohol misuse disorder. These comorbidities may also contribute to the increased disabilities and mortality rate, especially from cardiac events (Penninx et al., 1999), found in elderly people with depression. Elderly prisoners have particularly high rates of depression (Fazel et al., 2001).

The high prevalence of depressive disorder masks the fact that first episodes become less common after the age of 60 years, and rare after the age of 80 years. A new onset of mania or bipolar disorder in the elderly is very rare, and an organic cause (e.g. secondary to steroids) should always be suspected (Depp and Jeste, 2004).

The incidence of suicide, especially in men, increases steadily with age (see Chapter 16), and suicide in the elderly is usually associated with depressive disorder (Waern et al., 2002).

Anxiety disorders

In general practice, Shepherd et al. (1966) found that, after the age of 55 years, the incidence of new cases of neurosis (i.e. anxiety disorder) declined. However, the frequency of consultations with the general practitioner for neurosis did not fall—presumably as a result of chronic or recurrent cases. Subsequent larger population surveys have largely confirmed this view, although prevalence and incidence figures differ markedly between studies depending on the case definitions employed. For example, in a study from Liverpool, 1-month prevalence rates for ‘caseness’ for neurotic disorders were less than 1% in men and less than 2% in women over 65 years of age, whereas ‘subcase’ rates were about 20% in both sexes. In a 3-year follow-up, this corresponded to an incidence rate of 4.4 per 1000 per year. For a review, see Lindesay (2008).

Schizophrenia-like disorders

Schizophrenia-like and paranoid disorders in the elderly have been a long-standing source of debate and terminological confusion, as discussed in Chapter 12 (see Box 12.2), with the terms paraphrenia and late paraphrenia still commonly, if loosely, used. In future versions of ICD and DSM, the cumbersome term ‘very-late-onset schizophrenia-like psychosis’ will probably cover psychoses of this kind that arise after 60 years of age. The delineation of this group, and its separation from ‘late-onset schizophrenia’, which will apply to those with onset between the ages of 40 and 59 years, is based on differences in its symptom profile and associated risk factors (Howard et al., 2000).

Patients with ‘very-late-onset schizophrenia-like psychosis’ account for approximately 10% of admissions to psychiatric wards for the elderly. There are no reliable data on the prevalence in the community, as it is difficult to identify all cases of a condition in which many sufferers keep their experience to themselves and are unlikely to cooperate with ‘doorstep’ interviews. Also, in this setting, it may be difficult to distinguish cases from those with psychotic symptoms occurring in dementia or in severe depression.

Principles and practice of old age psychiatry

Having surveyed the epidemiological landscape, in this section we outline the principles and practice of old age psychiatry, in terms of service organization, assessment, treatment, and legal issues. The remainder of the chapter describes the specific features and treatments of the individual psychiatric disorders of old age.

Organization of services

An international consensus statement defined the essential elements of a mental health service for elderly people as follows (Wertheimer, 1997):

• primary healthcare team

• specialist old age psychiatry team

• inpatient unit

• rehabilitation

• day care

• availability of respite care

• range of residential care facilities

• family and social supports

• liaison with geriatric medicine

• education of healthcare providers about the needs of elderly people with psychiatric problems

• research, especially into epidemiological issues, and evaluation of services.

The ‘team’ concept is highlighted as being the key to effective provision of care (Banerjee and Chan, 2008), with multidisciplinary involvement being the norm. However, beyond these broad points of consensus, national policies have differed considerably in terms of the development of services and how they are implemented (Johnston and Reifler, 2000). In the USA, emphasis has been placed on care in hospitals and nursing homes. In Europe, Canada, and Australasia, there has been varying emphasis on social policies to provide sheltered accommodation and care in the community. In this section, services in the UK will be described as an example. Health, social, and voluntary services will be described separately, although good care depends on close collaboration at all levels, from strategic planning to the coordinated provision of care for each individual patient. Reflecting this need, health and social services, and their budgets, are now usually integrated in the UK. A National Dementia Strategy, ‘Living well with dementia’ (Department of Health, 2009), has been launched for England and Wales. It proposes three key steps:

1. Ensure better knowledge about dementia and remove stigma.

2. Ensure early diagnosis, support, and treatment for people with dementia and their families and carers.

3. Develop services to better meet changing needs.

Health services

Primary care

The general practitioner has a central role in assessment and management of the problems of mentally ill older people. In the UK, all patients over the age of 75 years are offered an annual health check, providing an opportunity for regular screening for psychiatric disorders. In many instances, the general practitioner, together with other health professionals in the primary care team and community health services, assesses and manages patients without referring them to a specialist. Even in the case of disorders for which referral will usually follow, such as dementia, the general practitioner is still responsible for the initial assessment and diagnosis (Turner et al., 2004). However, as already mentioned, general practitioners do not detect all of the psychiatric problems of the elderly at an early stage, nor do they always provide all of the necessary long-term medical supervision. These problems are due partly to lack of awareness of the significance of psychiatric illness among the elderly, and partly to a traditional service model in which doctors respond to requests from patients rather than seeking out their problems. Some old age psychiatry services will only accept referrals from a general practitioner, but increasingly referrals may be accepted directly from any source, although liaison with the general practitioner will always be important. In some areas, community psychiatric nurses (CPNs) work in primary care, although it is more usual for them to be part of old age psychiatry teams in secondary care.

Old age psychiatry services

The organization of psychiatric services varies in different localities, as it reflects the local styles of service providers, local needs, and the extent of provision for this age group by general psychiatric services, as well as national policies. Nevertheless, there are some general principles of planning. The aims should be to maintain the elderly person at home for as long as possible, to respond quickly to medical and social problems as they arise, to ensure coordination of the work of those providing continuing care, and to support relatives and others who care for the elderly person at home. There should be close liaison with primary care, other hospital specialists who may be involved, social services, and voluntary agencies. A multidisciplinary approach should be adopted with a clinical team that may include psychiatrists, psychologists, community psychiatric nurses, occupational therapists, and social workers. Some members of the team should expect to spend more of their working day in patients’ homes and in general practices than in the hospital. It is important that the care provided by these different agencies is coordinated, and in the UK the Care Programme Approach is intended to improve coordination by making a single person, the key worker or ‘care-coordinator’, responsible for ensuring that appropriate assessment, care planning, and review take place (see p. 607).

The contributions of the various parts of an old age psychiatry service will now be considered. In England and Wales, current severe financial constraints and the reorganization of the NHS to move control of budgets to general practitioners mean that the description of services for older people given below will inevitably change over the lifetime of this edition of this book. Although the basic principles and components of care may not change radically, the relative availability of these components may do so, and the reader will need to familiarize him- or herself with local conditions.

Domiciliary psychiatric care. Increasingly, assessment and treatment take place in the patient’s own home, which is both more convenient for the patient, and offers a more relevant and realistic assessment of the difficulties facing the patient and their carers. Community psychiatric nurses act as a bridge between primary care and specialist services. The nurses may assess referrals from general practitioners, monitor treatment in collaboration with general practitioners and the psychiatric services, and take part in the organization of home support for the demented elderly.

Outpatient clinics. These have a smaller part to play in providing care for the elderly than in providing it for younger patients, because assessment at home is particularly important for old people. However, such clinics are convenient for the assessment and follow-up of mobile patients. There are advantages when these clinics are staffed jointly by medical geriatricians and old age psychiatrists. In recent years, memory clinics have been developed in most areas for the specialist assessment of patients with early memory problems (Kelly, 2008). In the UK, these clinics also serve as the focus for prescription of drugs used to treat Alzheimer’s disease, since their availability is limited (see p. 500).

Day hospitals and day centres. Although some treatments can be provided at home, others may require the patient to attend a day hospital, where a high level of stimulation and social interaction can also be provided. In the 1950s, day care began in geriatric hospitals. A few years later the first psychiatric day hospitals for the elderly were opened. Psychiatric day hospitals should provide a full range of diagnostic services and offer both short-term and continuing care for patients with functional or organic disorders, together with support for relatives. Currently, day care is more often provided by day centres rather than in day hospitals. These centres combine health and social care elements, very often with the financial and practical involvement of voluntary organizations, such as the Alzheimer’s Society. Day centres provide an important and cost-effective component of the services available for the elderly with psychiatric problems. Day care has become a mainstay of care for those with mild to moderate dementia. All day-care-based arrangements depend crucially on adequate transport facilities.

Inpatient units. Inpatient teams should be able to provide multidisciplinary assessment and treatment of patients with severe disorders. In addition to psychiatrists and psychiatric nurses, these teams may include occupational therapists, psychologists, speech and language therapists, physiotherapists, social workers, healthcare assistants, and others. There is substantial variation in different areas both in the composition of the team and in whether patients with functional illnesses are cared for separate from or together with those with organic disorders.

Geriatric medicine. There is inevitably some overlap in the characteristics of patients treated by units for geriatric medicine and those treated in psychiatry units; both are likely to treat patients with dementia. However, old age psychiatry units are more likely to treat patients with functional psychiatric disorders. Earlier concern that many patients were ‘misplaced’ and therefore received poor treatment, stayed too long in hospital, and had an unsatisfactory outcome has not been confirmed by research. Copeland et al. (1975) found that although 64% of patients who were admitted to geriatric hospitals were psychiatrically ill, only 12% of them appeared to be wrongly placed. Moreover, their outcome did not appear to be affected adversely—many patients can be cared for equally well in either type of hospital. Optimal placement depends on the relative predominance of behavioural and physical problems. Medical and psychiatric teams need to cooperate closely if all patients are to receive appropriate treatment.

Long-term hospital care. In some countries, most elderly psychiatric patients are still treated in the wards of psychiatric hospitals. However, the nature of the care provided is more important than the type of institution in which it is given. The basic requirements are opportunities for privacy and the use of personal possessions, together with occupational and social therapy. Provided that these criteria are met, long-term hospital care can be the best provision for very disabled patients. In the UK, hospital provision of long-term care has been drastically reduced (with some increase in the level of community care), and long-term care is now largely provided outside hospital in residential and nursing homes. There is an active debate on how long-term care should be funded, as care provided by the NHS is free, whereas care provided through the social services is means tested (Royal Commission on Long Term Care, 1999). A statement from the Royal Commissioners in 2003 clarified payments for nursing and personal care. However, the more definitive Dilnot Commission report is still awaited, but should be published in the lifetime of this edition of this book (Commission on Funding of Care and Support, 2011).

Social services

Domiciliary services

In addition to medical services, domiciliary services include home helps, meals at home, laundry, telephone, and emergency call systems. In the UK, local authorities both provide and commission these services; they also support voluntary organizations and encourage local initiatives such as good-neighbour schemes and self-help groups. The last decade has witnessed a major shift in provider for these services, with the majority being from private or voluntary organizations. In a random sample of nearly 500 people aged 65 years or over living at home, Foster et al. (1976) found that 12% were receiving domiciliary services but a further 20% needed them. Although these provisions are increasing, so are the numbers of those requiring them. Bergmann et al. (1978) have argued that if resources are limited, more should be directed to patients living with their families than to those living alone. This is because the former can often remain at home if they receive such help, whereas many of the latter require admission before long, even when extra help is given.

Residential and nursing care

Older people may need a variety of social service accommodation, ranging from entirely independent housing through sheltered housing schemes, where there may be some communal provision, often including access to a warden, to residential or nursing homes where there are staff available at all times. There is a need for special housing for the elderly that is conveniently sited and easy to run. Ideally, the elderly should be able to transfer to more sheltered accommodation if they become more disabled, without losing all independence or moving away from familiar places.

‘Continuing care’ refers to the provision of homes where staff are available on site at all times. In residential homes, the needs of residents for help with personal care can be met by care assistants with relatively little training, whereas in nursing homes residents will require regular nursing care, and therefore the staff will include a substantial number of trained nurses. Some, but not all, nursing homes specialize in the care of older people with mental disorders.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree