32 Pterygopalatine and Infratemporal Fossae

Marc A. Tewfik and Peter-John Wormald

Introduction

Introduction

In the past, access to the pterygopalatine fossa (PPF) and infratemporal fossa (ITF) could only be achieved by either anterior or lateral approaches. Anterior approaches include midfacial degloving, lateral rhinotomy, extended maxillotomy/maxillectomy, facial translocation, and transantral maxillectomy approaches.1–3 Although these all provide good exposure for procedures such as internal maxillary artery ligation, vidian neurectomy, and removal of tumors of the PPF and anteromedial ITF regions, they are often complicated by facial scars and deformity, facial and infraorbital nerve dysfunction, as well as lacrimal dysfunction.2 Lateral approaches consist primarily of the Fisch C and D procedures,4,5 which offer excellent access to structures within the ITF, as well as the basisphenoid, clivus, and intratemporal course of the internal carotid artery. However, adverse outcomes include dysfunction of the facial nerve, conductive hearing loss, and dental malocclusion.3,6

Recent advances in endoscopic sinus surgery, and in interventional radiology with preoperative embolization, have enabled endoscopic surgical access to tumors of the PPF and ITF. Among these advances are improved instrumentation, computer-based surgical navigation, as well as hypotensive anesthetic techniques. In addition, the development of the two-surgeon transnasal approach7 has further facilitated access to the lateral ITF. However, an adequate level of experience in endoscopic sinus surgery as well as detailed knowledge of the endoscopic anatomy are necessary for any surgeon tackling pathology in these spaces. Although a comprehensive review of anatomy is beyond the scope of this chapter, the following pages provide an overview of the endoscopic transnasal approach to the PPF and ITF, beginning with a brief discussion of the structure and contents of these spaces.

Anatomy of the Pterygopalatine and Infratemporal Fossae

Anatomy of the Pterygopalatine and Infratemporal Fossae

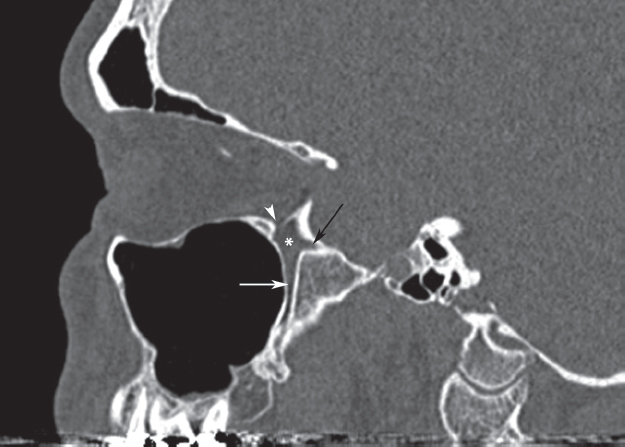

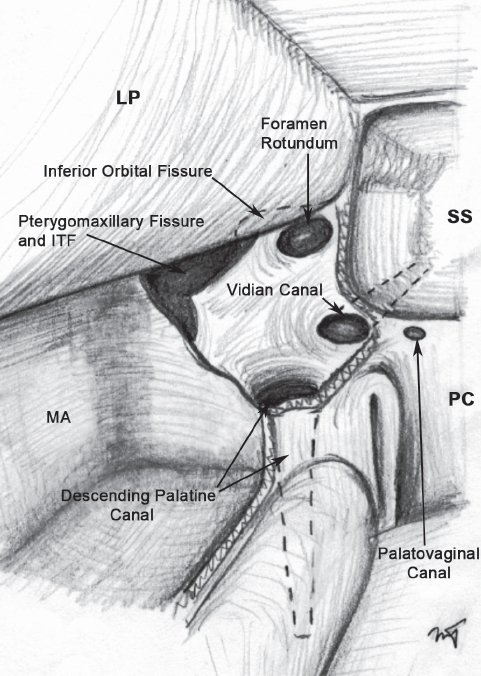

The PPF is a narrow space in the shape of an inverted cone, located between the posterior wall of the maxillary sinus and the base of the pterygoid process (Fig. 32.1). Its contents consist of fat, the sphenopalatine ganglion, the vidian nerve, the maxillary division of the trigeminal nerve (V2), and terminal branches of the internal maxillary artery. The fat and blood vessels lie anteromedial to the neural structures, and are therefore encountered first during the endoscopic approach. The pterygoid or vidian canal opens into the posterior aspect of the fossa. The vidian canal starts at the anterior genu of the petrous carotid artery and carries the vidian nerve along the inferolateral border of the sphenoid sinus until it reaches the PPF. The palatovaginal or pharyngeal canal also opens into the posterior aspect of the fossa just medial to the vidian canal (Fig. 32.2). The apex of the PPF is continuous inferiorly with the descending palatine canal, which opens into the oral cavity via the greater and lesser palatine foramina. The superior border consists of the undersurface of the sphenoid bone and orbital process of the palatine bone. Cranial nerve V2 passes from the middle cranial fossa to the PPF through the foramen rotundum, before giving off connections to the sphenopalatine ganglion, as well as branches to the orbit via the inferior orbital fissure. Medially, the PPF is separated from the nasal cavity by the perpendicular plate of the palatine bone, which also constitutes the anterior and inferior borders of the sphenopalatine foramen. Endoscopically, the ethmoidal crest is a reliable landmark along the lateral nasal wall, lying immediately anterior to the sphenopalatine foramen and artery.

Fig. 32.1 Computed tomography (CT) scan of the sinuses, parasagittal cut, through the pterygopalatine fossa (PPF; asterisk), demonstrating the foramen rotundum (black arrow), descending palatine canal (white arrow), and inferior orbital fissure (white arrowhead).

Fig. 32.2 Illustration depicting the PPF with the medial and anterior walls removed, demonstrating the foramina and openings along the inferior, posterior, superior, and lateral borders of the fossa. LP: lamina papyracea; MA: maxillary antrum; PC: posterior choana; SS: sphenoid sinus.

Laterally, the PPF is continuous with the ITF; they are divided by the pterygomaxillary fissure in the plane of the lateral pterygoid plate. The ITF is bordered laterally by the coronoid process, ramus of the mandible, and pterygoid muscles. As with the PPF, its anterior border is the posterior surface of the maxilla; however, its posterior border consists of the articular tubercle of the temporal bone and the spine of the sphenoid bone. The ITF is separated from the middle cranial fossa superiorly by the greater wing of the sphenoid bone, which contains the foramen ovale and foramen spinosum; they transmit the mandibular division of trigeminal (V3) and the middle meningeal artery, respectively. The alveolar border of the maxilla delineates the inferior margin of the ITF. The relationships between these various structures are important in helping the surgeon identify and preserve those that are normal, and fully remove pathologic tissue.

Indications and Advantages of the Endoscopic Approach

Indications and Advantages of the Endoscopic Approach

The endoscopic approach to the PPF is indicated for internal maxillary artery ligation in patients with uncontrolled posterior epistaxis and in whom ligation of the sphenopalatine and posterior nasal arteries has failed,8 for vidian neurectomy in patients with refractory vasomotor rhinitis,9 and for the repair of laterally based meningoencephaloceles.10 Given that the PPF and ITF are adjacent and continuous spaces, masses that arise in one space can easily spread to the other. Such masses include juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibromas (JNAs), maxillary nerve schwannomas, large inverting papillomas, and large temporal lobe meningoencephaloceles.7

The advantages of the endoscopic technique are numerous, including the avoidance of adverse outcomes associated with open approaches, such as facial incisions, hearing loss, and nerve dysfunction. Relatively straightforward access is achieved to the PPF and ITF, areas traditionally considered difficult to reach. The endoscope provides a magnified and multiangled view for more precise discrimination of the dissection planes between the tumor and the adjacent structures. Furthermore, the two-surgeon technique offers improved surgical control by providing a second surgeon for tumor retraction and additional assistance for suctioning in the event of brisk surgical bleeding.

Contraindications

Contraindications

Given the continual refinements in surgical technique and instrumentation, it is unlikely that the limits of endoscopic resection of tumors in the ITF have been achieved. Tumors extending into the masseteric space, buccogingival sulcus, middle cranial fossa, parasellar region, and cavernous sinus, as well as around the optic nerve and orbital apex, present challenges to endoscopic resection. However, these regions are also very difficult to access via open approaches, and in skilled hands these regions can all be approached endoscopically. There is an ongoing controversy over the role of endoscopic resection for malignant neoplasms; such an approach may be acceptable in select malignancies, as long as it does not compromise the completeness of oncologic resection. However, certain malignant tumors, such as squamous cell carcinoma, tend to fare poorly due to their extensively infiltrative nature, and so are not recommended for endoscopic resection.

Diagnostic Workup

Diagnostic Workup

Clinical Assessment

The clinical history and physical examination are important in obtaining the diagnosis of lesions extending from or into the ITF. The most common nasal tumor with ITF involvement is JNA. It has the classical presentation of recurrent unilateral epistaxis in teenage or young adult males. If it is suspected in a female patient, karyotyping should be obtained to rule out an androgen insensitivity syndrome. A history of seizures may be seen in tumors with significant intracranial extension via the foramen rotundum or in large meningoencephaloceles.

The physical examination should include assessment of cranial nerve function, along with extraocular movements and visual acuity. If any orbital or optic nerve involvement is suspected, a complete ophthalmologic evaluation is warranted. Rigid nasal endoscopy is performed to assess for masses with an intranasal component, as well as for the detection of septal deviation, unusual nasal anatomy, or other obstacles to endoscopic access.

In most cases, the diagnosis of these tumors is self-evident, without the need for histopathology. However, if there is significant doubt as to the diagnosis, then histologic confirmation may be required. Careful review of imaging is essential because biopsy of a highly vascular lesion may result in catastrophic hemorrhage.

Imaging Studies

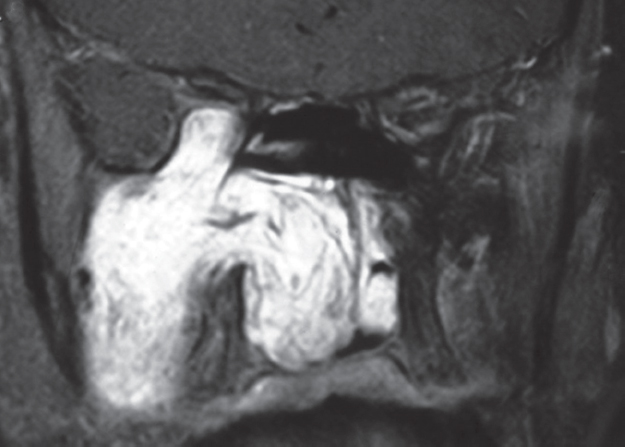

Computed tomography (CT) provides useful information regarding bony sinus anatomy, the position and integrity of the lamina papyracea, as well as involvement of the ethmoid and sphenoid sinuses. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is essential in determining the relationship of tumors to critical structures. Tumor extension through the inferior orbital fissure into the orbital apex and cavernous sinus needs to be identified and a plan developed for the removal of the tumor from this region (Fig. 32.3). The other critical region is the vidian canal. Tumor will often infiltrate the clivus, and occasionally reach the carotid artery by expanding along this canal (Fig. 32.4). Within the ITF, the relationship of the tumor to the middle cranial fossa, buccogingival sulcus, and masseteric space also needs to be ascertained, to decide whether this tumor can be safely resected using the endoscope and two-surgeon technique. High-resolution CT or MRI scans specifically suitable for image-guided surgical navigation should be obtained preoperatively.

During the 24 hours preceding surgery, an arteriogram is performed to establish if there are any significant feeders from the internal carotid or internal maxillary arteries. If this is the case, a highly selective embolization of all feeding vessels is performed. It is important that arteriography be performed bilaterally, as tumors can receive feeding vessels from both sides. With large tumors, a repeat arteriography and embolization of any remaining vessels may be useful immediately before surgery. We have found that this significantly reduces the vascularity and intraoperative bleeding in comparison to large tumors that had only been preoperatively embolized once.

Fig. 32.3 T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the sinuses demonstrating a gadoliniumenhancing juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma (JNA) extending superiorly from the PPF though the inferior orbital fissure and compressing the contents of the orbital apex.