CHAPTER 109 Radiologic Features of Central Nervous System Tumors

Principles of Diagnosis by Neuroradiology

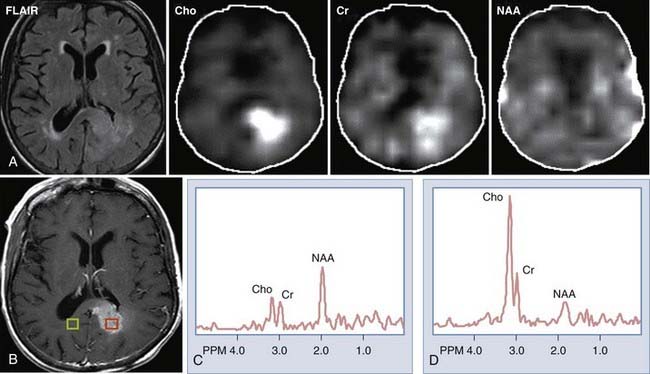

Spectroscopy

MRS provides information regarding the biochemical milieu within a relatively small volume of interest. Although it began, and is often still used, as a single voxel technique—gathering data from a usually cubic volume measuring between 1 and 2 cm—more modern implementations of MRS allow for acquisition of MRS data from arrays of smaller voxels (usually about 1 cm3 depending on the technical attributes of the imaging system) localized in multiple coplanar sections. These MRS imaging techniques can provide information on spatial variation in biochemical markers that can be used to distinguish among different types of tumors, and that can roughly index a lesion’s degree of malignancy (Fig. 109-1). Among the major markers are N-acetyl aspartate (NAA), choline, creatine, myoinositol, lactate, and lipid. Relevant spectroscopic features of different lesions are discussed throughout this chapter, but a general rule of thumb is that the more malignant the lesion, the lower the NAA and the higher the choline concentrations.

Cerebral Blood Flow and Volume Estimates

Measures of cerebral blood flow (CBF) and cerebral blood volume (CBV) within tumors using MRI1–4 or, more recently, CT5,6 provide quantitative correlates of what has been known since cerebral angiography as one of the mainstays for brain tumor localization and characterization, that is, that tumors frequently contain dysplastic blood vessels that exhibit blood (contrast) transit time that is markedly slower than is that within the surrounding parenchyma. In the case of many tumors, catheter angiography would demonstrate a tumor blush, indicative of an abnormally enlarged blood pool. MRI or CT perfusion data correlate reasonably well with tumor grade, with higher grade tumors exhibiting greater CBV.1,7–9 There is also some evidence that blood volume measurements have prognostic value, with low-grade tumors that have higher blood volumes advancing in grade more rapidly than tumors with similar histology but lower blood volumes.10

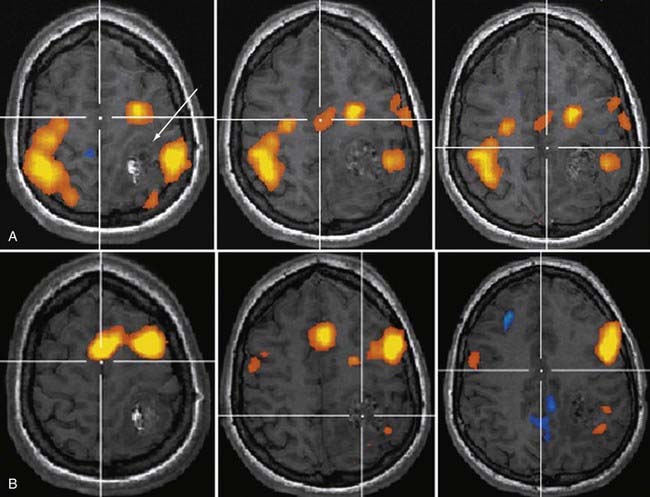

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging

The early 1990s saw the development of imaging techniques which could assay dynamic changes in blood flow and blood oxygen extraction as a proxy for regional brain neural activity.11,12 These techniques became known as fMRI and were based on the observations that the concentration of deoxyhemoglobin in blood affected the nuclear magnetic resonance parameter known as T2*—with a higher concentration being associated with a shorter T2*13—and that with brain activation, there is an increase in regional cerebral blood flow out of proportion to the increase in oxygen extraction.14 With regional brain activation, the disproportionate increase in blood flow compared with oxygen extraction leads to a higher concentration of oxyhemoglobin in the venous efflux and thus a reduced concentration of venous deoxyhemoglobin. The reduced concentration of deoxyhemoglobin and concomitant prolongation of T2* leads to a regional task-related increase in signal.

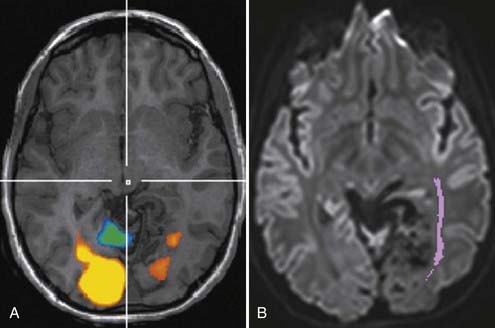

Soon after its introduction, investigators proposed fMRI as a tool in preneurosurgical planning15 and established that its ability to localize primary sensorimotor cortex compared reasonably well with electrophysiologic techniques.16–19 In the neurosurgical setting, the earliest and probably still most common applications of fMRI have been in localizing the hand-arm representation in the primary sensorimotor regions, although with the development of a broad array of paradigms, interrogation of language-related brain regions has become virtually as common (Fig. 109-2). fMRI has been shown useful in demonstrating the degree to which regions of eloquent cortex have been displaced by tumors or have undergone reorganization because of regional cortical dysplasia or dysfunction.20,21 In 1999, Lee and colleagues at the Mayo Clinic published a summary of their experience using fMRI in the setting of presurgical evaluation of tumor and seizure patients.21 They found that they were able to use fMRI to identify the primary sensorimotor region in 70% of patients; their success rate was close to 90% when they considered only the patients they evaluated using more recently developed data acquisition techniques.

Like any technique, fMRI does not always work; the patients who are being evaluated frequently move more than healthy volunteers, which will almost certainly have an adverse effect on the quality of the data,22 as will reduced vasoreactivity in the vicinity of tumors or vascular malformations. As techniques have improved over time, especially for rapid data acquisition and for patient motion correction, the applicability of fMRI as a neurosurgical planning tool has increased.

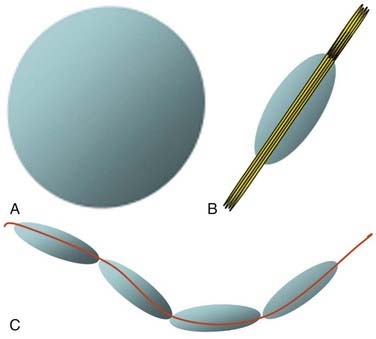

Diffusion Tensor Imaging and Tractography

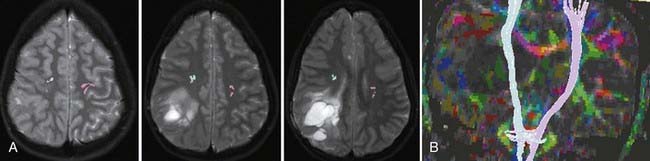

Although fMRI to estimate the proximity of functional cortex to a tumor has been available since the mid-1990s, techniques for estimating the proximity of major white matter tracts have developed much more recently, and as of this writing (mid-2008) remain under active development. These techniques are based on the biophysical observation that water molecules within axons move in a relatively unconstrained manner longitudinally along the length of the axon, whereas those molecules can move only a short distance radially before they encounter either microtubules or the axonal membrane.23–26 Thus, if one were to measure and plot within any given imaging voxel the ability of water molecules to move in a relatively unconstrained way, one would end up with a blimp or cigar-shaped plot, oriented roughly along the axes of the axons that run through that voxel. This plot represents graphically what is known mathematically as the diffusion tensor. Conceptually, by assessing the directionality of water diffusivity in each small imaging voxel and then linking the measures of maximal diffusivity end to end, one can begin to discern the trajectories of white matter tracts as they run through the brain (Fig. 109-3, and Fig. 109-4 for a clinical example). Ongoing technical developments include improvements in tracking white matter bundles through edema surrounding tumors (and even through tumors) and in separating white matter tracts that closely approximate one another, or that cross one another within a group of voxels.27–31

Often fMRI and DTI-tractography results can be used complementarily because in the vicinity of brain tumors or vascular malformations, the coupling between neural activity and the reactive changes in blood flow on which fMRI signal changes depend is often impaired. In such cases, the fMRI data may be of reduced utility, whereas the tractographic data may still be quite robust (Fig. 109-5). Conversely, extensive edema may render the tractographic data suboptimal, whereas the fMRI signal changes in the overlying cortex remain relatively unaffected.

Features that suggest that masses are intra-axial include the following:

Extra-Axial Masses

Meningioma

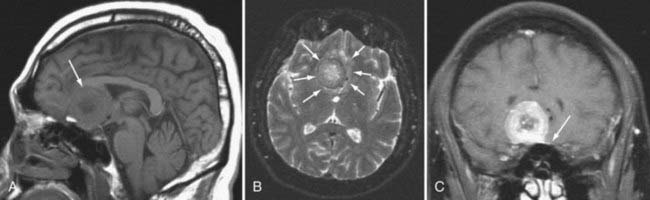

By far, the most common extra-axial neoplasm to affect the intracranial compartment is the meningioma. This tumor is characterized by hyperdensity relative to normal brain parenchyma on CT, isointensity on T1-weighted images relative to gray matter, and slight hyperintensity on T2-weighted images (Fig. 109-6). It should be noted, however, that there is a wide variety of signal intensity characteristics associated with meningiomas, and in fact, some reports suggest that syncytial, transitional, and angioimmunoblastic meningiomas may have differing signal intensity characteristics depending on their internal histology. Nearly all meningiomas show strong contrast enhancement on either CT or MRI. Meningiomas may show stippled or confluent calcification. If the meningioma is extensively calcified, enhancement may be less evident.

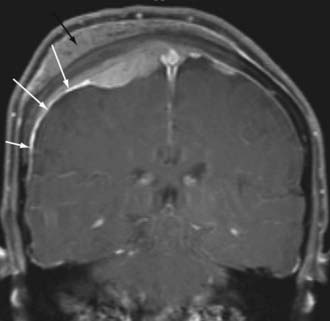

Meningiomas also have a characteristic “dural tail,” which represents contrast enhancement extending along the margins of the tumor affecting the pachymeninges (Fig. 109-7). Some histologic studies have suggested that the entirety of the dural tail represents meningioma tumor, whereas others have suggested that this may represent reactive change adjacent to neoplasm.32

The spectroscopic features of meningioma on proton spectroscopy include absence of NAA and elevations of choline peaks. The height of the NAA and creatine peaks may be markedly reduced. Alanine has been suggested to be a specific marker for meningiomas, but its presence is variable.33–35 Although this may help differentiate a meningioma from an intra-axial mass, many other extra-axial masses (see later) have a similar spectroscopic signature.

Meningiomas may deviate from the characteristic benign appearance in many different ways and on occasion demonstrate necrosis, fatty degeneration, cystic areas, infiltration into the brain, infiltration into the bone, and marked vasogenic edema.36 The presence of vasogenic edema associated with meningiomas has been correlated with the lesion size as well as the degree of parasitization of dural venous structures.

On dynamic imaging with contrast agents, the meningiomas show slow uptake of the contrast agent in a continuous fashion followed by a lengthy period of stable enhancement and a delayed clearance of the contrast agent. MRI-based estimates of CBV has been shown to help differentiate between meningioma and dural-based metastatic deposits, with the meningiomas typically showing substantially greater CBV.37 Angiographically, dural vessels generally supply the lesions. This usually means that the branches of the external carotid artery, including the middle meningeal artery or stylomastoid branches of the occipital artery, supply the mass. Nonetheless, branches of the tentorial artery from petrous carotid meningeal branches may be responsible for the primary supply of tentorial meningiomas. Similarly, meningiomas around the cavernous sinus may have direct carotid branches supplying the lesion. Meningiomas at the foramen magnum may receive blood supply from branches of the vertebral artery or posterior inferior cerebellar artery.

Schwannoma

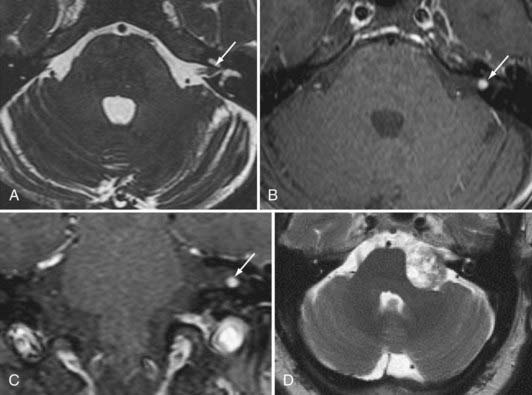

The next most common extra-axial mass is the schwannoma, dominated by those that occur in and around the internal auditory canal. This lesion characteristically resides in the cerebellopontine angle or in the internal auditory canal, arising most often from the vestibular branches of the 8th cranial nerve (Fig. 109-8). Its imaging characteristics are similar to those of a meningioma from the standpoint of being relatively isointense to gray matter, but the absence of a dural tail usually helps to distinguish these two lesions. Vestibular schwannomas, however, may show cystic degeneration as well as hemorrhage and occasionally cause edema in adjacent brain tissue. As opposed to meningiomas, it would be highly unusual for an acoustic schwannoma to cause bony lysis or bony sclerosis. In particular, if a cerebellopontine angle lesion shows enhancing tumor entering the internal auditory canal, one would favor vestibular schwannoma over meningioma.

Epidermoid

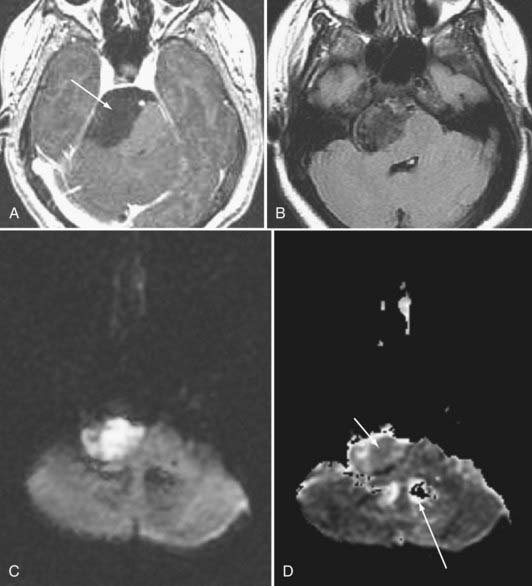

Epidermoid tumors may arise in the cerebellopontine angle, the suprasellar cistern, the diploic space, the peripineal region, or the middle cranial fossa. These lesions do not as a rule exhibit contrast enhancement. Epidermoids have signal intensity appearances that are pathognomonic: (1) very high signal intensity on T2-weighted images, (2) signal intensity close to that of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) on T1-weighted images, (3) higher signal intensity than CSF on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) MRI and diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), (4) restricted diffusion that typically is depicted as low signal on apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) images, and (5) absence of enhancement (Fig. 109-9). Epidermoid lesions tend to have a crenated margin and will infiltrate adjacent structures, particularly along the brainstem. The usual differential diagnosis with the epidermoid is the arachnoid cyst. Epidermoids can be distinguished from the latter because arachnoid cysts are as dark as CSF on FLAIR, diffusion, and steady-state free precession imaging. The signal intensity of epidermoids will not simulate CSF on these sequences.38 The arachnoid cyst is also more sharply delineated than is the epidermoid.

Proton spectroscopy may help in some instances of cystic masses in the brain. Although cystic astrocytomas show NAA, choline, and creatine peaks (with or without lactate), epidermoid cysts show only lactate signal. There are no identifiable resonances from arachnoid and porencephalic cysts.39

Pineal Region Tumors

Germinomas and Germ Cell Tumors

More than half of germinomas are denser than normal brain tissue on CT, and the remainder are isodense. Sometimes, the tumoral tissue surrounds the normal pineal gland, resulting in an engulfed appearance to the calcification (Fig. 109-10). Isointensity to low intensity on T1- and T2-weighted MRI is also the norm. Avid homogeneous enhancement characterizes germinomas. Cystic change occurs in 33% of pineal region, 28% of suprasellar, and 80% of basal ganglionic germinomas.40,41 CSF seeding occurs in 50% of pineal region, 28% of suprasellar, and 30% of basal ganglionic germinoma. Response to radiation therapy may be dramatic, with scans showing no evidence of tumor within 2 weeks after completion of radiation therapy.40 In some instances, complete resolution may not take place for 6 months after radiation. With treatment, the tumor may become hypodense and brighter on T2-weighted and FLAIR images. The presence of cystic change portends a worse response to radiation therapy (33% complete resolution if the mass is cystic, versus 90% without a cyst).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree