Case Report A6 Achieving Functional Outcomes with Neuro-Developmental Treatment for Chronic Stroke Research is now beginning to demonstrate that individuals recovering from stroke can be expected to change and make progress for a long period of time after their stroke.1,2 However, therapists treating clients with adult-onset neurological diagnoses such as stroke are frequently challenged because they treat these individuals for only short bursts of time within the scope of their work environment (i.e., acute care, inpatient rehabilitation, subacute care, home care, outpatient therapy, etc.). Even if the client remains in the same facility, a particular therapist may treat the individual for only a short period before the client is transferred to another program or service. Recent research has attempted to determine the most effective setting for rehabilitation in the early poststroke period (rehabilitation unit, home-based, etc.).3 In addition, research has begun to examine therapy outcomes in the time period referred to as chronic stroke, which usually includes up to 1 year after the stroke.4,5 Information is lacking about therapy, recovery, and outcomes, or even about new problems or challenges, in the longer poststroke period that includes up to 5 or more years after the stroke.6 Due to the individual’s changing need for care and the nature of the medical system, it is likely that the members of the client’s therapy team will change throughout the recovery process. This change challenges the continuity of care from the client’s perspective, and it makes it difficult for the therapist to fully understand or anticipate an individual client’s progress or potential (i.e., how limited the individual was at onset, or how able and functional he or she is able to become 3, 4, or 5 years post onset.) It is difficult, for many reasons, to demonstrate potential for functional change in individuals with chronic stroke. One reason is the difficulty in compiling a homogeneous group of individuals with stroke to use for comparison. Inherent in the definition of a controlled trial is the idea that the intervention is standardized, and that, therefore, the randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) that have investigated intervention have generally addressed defined and discrete interventions that could be standardized.5,7 However, the rehabilitation of an individual with impairments in many systems that change on a daily basis requires that the therapist create and implement a constantly changing plan to address those needs, not apply a standard set of procedures. Studies that have purported to investigate the effectiveness of an approach have usually narrowed the approach to a few specific activities or techniques, eliminating much of the ongoing problem solving and modification that, by definition, is part of the approach. In addition, studies that have attempted to show the superiority of one approach over another have generally shown a small difference or no difference. We must proceed with caution when interpreting these studies because failure to show a difference between approaches does not mean that the approaches are ineffective. Both approaches may be effective, and it may not be clear that one is better than the other.8,9,10 Although case study research has recently gained legitimacy as an additional means to guide clinicians to successful interventions, clinicians may not have the time or resources to perform even formalized case studies. Use of a case report, with careful measurement of objective outcomes and delineation of the problem-solving process used to develop and modify the interventions, can provide additional information to increase the therapist’s awareness and responsibility for the care plan’s effectiveness, and it can also guide intervention with other clients.11,12 The clinician can measure intervention success in several important ways with an individual client. Sackett et al13 remind us that we must consider current evidence as well as the subjective preferences of the individual being treated. Therefore, objective measures of functional change as well as the client’s subjective opinions of what has changed and what is relevant to the client will determine effectiveness of the intervention to date and will guide further intervention, if appropriate. Most research that examines progress and outcomes in individuals with chronic stroke focuses on the first year (+/−) poststroke. Furthermore, because stroke is often considered to be a problem of aging, research has not emphasized the progress and/or problems of persons living with stroke over the long term. Population studies to determine the causes of stroke at various ages have led to increased awareness of these long-term survivors of stroke and their physical, emotional, and vocational needs.14,15 Although there is increased awareness of the existence of long-term survivors of stroke, studies of interventions over a 5-year period have each generally focused on a specific intervention—whether it is effective and for whom.5 Studies have not generally been designed to determine how to choose the best interventions or the optimal time frame, frequency, or duration of interventions for a particular individual. As Mant16 states, “The paradox of the clinical trial is that it is the best way to assess whether an intervention works, but is arguably the worst way to assess who will benefit from it.”16 Along with increased interest and emphasis on research-based intervention, there has been increased interest in the ability to define and describe the clinical decision-making process. Early in our professions, we recognized expert clinicians who seemed to have developed intuition that guided them to be especially effective with their clients.17 Interest in defining this process of intuition and decision making has gradually provided use with models and schemes to guide our decision making. Use of an enablement/disablement model continues to help us to organize and link our data and thought processes. Current models describe the examination and evaluation processes in detail.18,19,20,21 The process of linking the specific impairments that are most responsible for the activity limitations is being explored, although to a lesser extent.19,22 Neuro-Developmental Treatment (NDT) provides the therapist with tools to understand and address this linkage between functional activity limitations and the specific impairments that are most responsible.23,24 Primarily, NDT provides the therapist with the ability to analyze tasks, movements, and postures from many perspectives and in great detail to determine the multisystem impairments or posture and movement problems that are present.25 From here, the therapist determines and prioritizes the specific single-system impairments that are most responsible for a specific activity limitation.26 In addition, a second major tool of NDT, the use of therapeutic handling, provides the therapist with additional information about aspects of an individual’s impairments, especially those of the neuromotor system that are particularly difficult to differentiate (e.g., the type and duration of muscle activation, location of initiation of muscle activity to perform a movement pattern, etc.) In this way, the therapist using NDT is more prepared to assess and intervene with the individual’s specific impairments most effectively and efficiently during the intervention phase, using NDT handling as well as other skills, to achieve the desired participation and activity outcomes as efficiently as possible. This case report describes problem solving and decision making during episodes of care in physical therapy with Dennis, a 62-year-old man recovering from a stroke over a 5-year period. Particular emphasis will be on the use of the NDT Practice Model to (1) assess and treat his activity and participation limitations and (2) address the underlying system impairments that contributed to these limitations, particularly the specific limitations in the neuromotor system. Specific functional outcome measures as well as meaningful qualitative changes in function are reported, along with a discussion of the thought processes and prioritization that lead to these changes, to illustrate Dennis’s progress over a 5-year period. Dennis had been treated in acute care and inpatient rehabilitation, and he had had some outpatient intervention when he was referred for an outpatient physical therapy evaluation in March 2006. His primary stated goal was to improve his mobility, especially his walking, to return to his previous activities, such as walking, biking, and traveling. He had been relatively healthy and active until July 2005, when he suffered a right frontal intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) at age 57. During the initial information gathering, Dennis’s physical therapist (PT) performed the objective portion of the examination and directed conversation toward assessment of contextual factors to determine what was important to him and what factors might enhance or limit Dennis’s progress in physical therapy. Most of Dennis’s time would be spent outside of therapy, so his PT needed to understand Dennis’s lifestyle, motivation, and family environment to help him achieve changes in function. Dennis’s wife, Marilyn, accompanied him during the initial session, and she gently helped him answer questions when he had trouble remembering parts of his recovery. Medical records of his hospitalization contributed additional details of his history. In addition to the ICH, Dennis’s additional medical diagnoses included hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, mild hearing loss, and mild depression in the past. His hospitalization for the ICH included 10 days in acute care and 5 weeks in inpatient rehabilitation. He initially received outpatient physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy, but at the time of this outpatient physical therapy evaluation (8 months post onset), he had been discharged from occupational and speech therapy. Dennis and his wife were interested in receiving a second opinion regarding whatever physical therapy options might be available to address his significantly increased tone and spasticity, especially in his left lower extremity (LLE). Dennis and his wife have three grown children and three grandchildren who are available to provide significant assistance. Both Dennis and his wife are retired school administrators, and Dennis had been continuing to work part-time until his stroke. Dennis had enjoyed walking, biking, reading, and watching movies prior to his stroke, and he and Marilyn planned to travel and spend more time with their grandchildren during retirement. Four important questions guided and helped organize actions and thought processes during the examination and evaluation: What? How? Why? So what? These questions guide physical therapy examination and evaluation through the NDT Practice Model to provide a basis for the plan of care. Because Dennis was a relatively high-functioning outpatient, his therapist collected data about activity through a combination of observation, hands-on assessment, and client report. She observed Dennis’s posture and movement and let his answers to specific questions guide further assessment. Questions became more specific and focused as the PT learned more about his mobility, lifestyle, and goals. To gather data about Dennis’s functional/activity status, the PT initially asked what questions, such as, “What can you do?” “What activities are difficult or impossible for you?” Dennis’s answers guided decisions about specific functional outcome measures that would effectively show his current status as well as his anticipated progress in functional activities (Table A6.1). From the moment the therapist began escorting Dennis to the intervention area, she began to look for answers to how questions. She asked, “How is he getting his center of mass forward to shift from sitting to standing?” “How is he shifting weight and moving his center of mass forward when walking?” “How is he aligned when sitting unsupported?” “How much weight is on his left side versus his right side during each activity?” The answers to these questions described the characteristics of Dennis’s posture and movement. These descriptions of how Dennis moved (e.g., left knee hyperextended, trunk rotated to the right) explain the multisystem impairments that, once analyzed, provided the critical link between data collection, evaluation, and subsequent intervention. Determining multisystem posture and movement impairments is the first step toward determining the underlying specific and significant single-system integrities and impairments that contribute to Dennis’s current functional activities and activity limitations. Although observation initially provided some information, the use of hands-on assessment, which is one of the hallmarks of NDT, enhanced the ability to answer how questions with hypotheses of how the specific single-system impairments contributed to Dennis’s limitations in function and which impairments were the most significant. Questions such as, “When he shifts excessively to the right during sit to stand, do I feel a push from the LLE that pushes him right, or does the initiation of the asymmetrical weight shift feel like it is coming from a forward lean initiated by the upper body?” or possibly, “Do I feel that the force pushing him forward is coming from his use of his stronger right arm to push on the chair?” assisted in identification and prioritization of system impairments. Table A6.1 Dennis’s Status in the Activity Domain—Initial Evaluationa

A6.1 Introduction

A6.1.1 Rehabilitation for Chronic Stroke

A6.1.2 Increased Acceptance for Case Study Research

A6.1.3 Need for and Adequacy of Functional Outcome Measures

A6.1.4 Decision-Making-Process Research

A6.1.5 Purpose

A6.2 Information Gathering

A6.2.1 Client

A6.2.2 History

Medical

Social Context

A6.3 Examination

A6.3.1 Activity and Activity Limitations

Activities—“What can you do?” | Activity limitations—“What is difficult or impossible for you to do?” |

• Independent in bed mobility. | • Bed mobility is slow. |

• Walks independently in his home. | • Getting up from chair is difficult, often requires several attempts and cannot be done safely without the ankle-foot orthosis (AFO) due to severe inversion and plantar flexion of his left ankle. |

• Goes out on short community outings with wife. | • Walking is very slow and requires use of AFO. |

• Performs car transfer with supervision. | • Walking in community requires cane and close supervision. |

Additional information: | |

• Is left-handed—can do mostly what he needs to do with his left hand. | • Is unable to go for long walks. |

• Reports a recent near fall (onto couch). | |

• Reports that handwriting is “getting better.” | • Needs assist for safety in the shower (foot twists, has difficulty getting leg over edge of tub). |

• Requires support from furniture and supervision for floor transfer. | |

• Requires railing, supervision, and verbal cues for stair ambulation. | |

• Doesn’t drive. | |

Additional information: | |

• Reports problems reading. | |

• Reports short-term memory problems. |

a Answering the what question.

Use of observation and hands-on assessment allowed comparison and reconsideration of findings during Dennis’s evaluation. For instance, during observation of gait, Dennis’s upper body was aligned slightly forward, and the left hip (affected side) was slightly flexed with his pelvis rotated posteriorly throughout stance. Initially, the therapist hypothesized that possible causes of this pattern might be insufficient hip extension strength or a limitation in hip extension range on the left. With continued hands-on assessment to feel movement, activation, and timing, the therapist was able to feel that Dennis was initiating the forward progression during gait incorrectly, attempting to pull his body forward by leaning forward with his upper body. His timing and sequencing for forward progression could be felt to be via upper body initiation rather than through use of the force of his LLE against the floor to provide forward propulsion. This upper body initiation, combined with Dennis’s best attempt strategy for maintaining balance during stance on the left, resulted in a flexed, posteriorly rotated position of his left hip. When the therapist attempted to assist Dennis’s hip extensors, she did not feel a limitation in hip extension range but felt that the forward movement of the upper body limited her ability to assist the hip to stay extended. Although the therapist felt less hip extension activity than expected, handling helped prioritize that the incorrect initiation of forward progression was a significant movement problem.

Table A6.2 delineates some of Dennis’s other multisystem posture and movement integrities and impairments observed and felt during the initial evaluation. As his therapist assessed and provided intervention in the different positions and activities of the intervention plan, she continued to revise and update this list of multisystem integrities and impairments by comparing observations with what she felt through hands-on assessment.

A6.4 Evaluation

Once Dennis’s therapist collected information about his multisystem impairments (as described in Table A6.2), it was time to ask why to determine which specific systems, as well as which specific underlying impairments within individual systems, were most responsible for his problems with function. For example, the multisystem impairment of decreased weight bearing on the LLE that was observed and felt during sit to stand could be caused by impairments in the musculoskeletal system, the neuromotor system, or the perceptual system, or by a combination of impairments in several systems.

The information gained about Dennis through observation and handling continued to be compared, associated, and linked to the different pieces of data, as in a jigsaw puzzle, to determine their relationships. Continuing to ask why resulted in organized, prioritized, and further testing to hypothesize the single-system impairments that were most responsible for his activity limitations. This examination and evaluation thought process continued throughout sessions with Dennis and provided the basis for the documentation included in the initial report, monthly plans of care (POC), daily notes, and correspondence with the physician and insurance company. Explanation of this thought process was one important way in which the therapist justified Dennis’s need for skilled physical therapy intervention.

Part of the evaluation is gathering information about multi- and single-system impairments and then prioritizing them so that the intervention strategies designed are specifically directed toward addressing the single-system impairments that are most significant and limiting to Dennis’s function. Addressing the how (e.g., just facilitating a more symmetrical weight shift) will not achieve results as quickly as determining the underlying why—addressing the cause of the asymmetry—and then reeducating use of a more symmetrical movement pattern for function. Strategies for remediating single-and multisystem impairments would be linked together to form an effective plan to achieve the activity and participation goals upon which Dennis and his therapist agreed.

Dennis demonstrated impairments in the neuromotor system, as expected, but also in the sensory-perceptual and musculoskeletal systems (as described in Table A6.3).

Dennis’s musculoskeletal and sensory-perceptual systems were screened, rather than performing detailed tests and measurements during the evaluation session, because time to focus on these details would have detracted from other assessment that was felt to be more informative. To determine his progress it was necessary to obtain the desired objective measures early in the examination to establish an objective baseline. His specific problem areas were assessed in detail as needed in later sessions.

So what? This question relates to the participation domain, or to the things that are meaningful in the client’s life. Because Dennis’s cognition was relatively good, his wife was with him, and he was living at home (not hospitalized), it was relatively easy to direct discussion toward meaningful short- and long-term functional outcomes. This discussion also helped clarify the personal and environmental contextual factors that might influence Dennis’s recovery (Table A6.4).

An individual contextual factor may be positive at some points and negative at others. Negative contextual factors can also sometimes be used as a source of meaningful functional goals. For example, Dennis and his wife lived in a two-story home with steep stairs. When Dennis was initially evaluated, his wife expressed concern regarding Dennis’s safety while going up and down; she was providing hands-on guarding. This challenging mobility task later became an opportunity and a goal for Dennis. He gradually demonstrated progress, becoming able to negotiate the stairs using the railing with only supervision, and later without a constant hand on the railing, so that he was eventually able to carry items with one and then two hands while going up and down the stairs.

Table A6.2 Some of Dennis’s multisystem posture and movement integrities and impairments

Multisystem posture and movement integrities | Multisystem posture and movement impairments |

• Shifts weight onto affected side without support when cued in sitting and standing. • LLE supports weight in standing and walking. • Trunk alignment is relatively symmetrical; muscle activation is felt on both sides of the body. • Uses active movement of LUE functionally for a variety of tasks. • Head is aligned relatively in midline during most activities. • Moves his LLE actively through part range at most joints. • Balances in standing without hand support to perform two-handed tasks. • Shifts the upper body mass forward to begin sit to stand. • Controls most of movement lowering from stand to sit. • Alignment of the LLE in standing is relatively good, but better proximally than distally. • Activates muscles in the LLE for functional tasks such as sit to and from stand and gait. | Sit to stand: |

• Increased effort is observed with weight shift forward to come to stand; several attempts are needed, at times, to achieve standing position. | |

• Weight shift is asymmetrical, with more weight on the right; movement forward is asymmetrical with the right side of body coming forward more effectively via hip flexion. | |

• Dennis attempts to use momentum, including momentum of UEs, to assist with achieving forward weight shift (when not using UEs to push on surface to assist with the motion). | |

• LLE abducts and externally rotates during forward weight shift and hip flexion. | |

• Tibias do not translate forward with ankle dorsiflexion during the initial phase of sit to stand; left translation is less than right. | |

• Dennis’s upper body can be felt to be leaning more and more to the right as he comes to stand; this lean is exaggerated when he uses his right arm to push up. | |

• When facilitated to stay in a more symmetrical posture, resistance to left hip flexion is felt; the LLE is felt to be actively pushing his mass to the right instead of forward toward his feet as he moves from sit to stand. | |

• Left ankle strongly inverts during sit to stand and cannot be held in correct position through the transition by therapist using facilitation at ankle and foot. | |

• When the therapist aligns Dennis’s left foot and ankle in sitting, and when the weight shift is facilitated correctly forward, there is a passive resistance to hip flexion on the left—hip flexion feels “blocked”; more hip flexion range is available during forward weight shift if the hip is allowed to abduct and the ankle is allowed to invert, but the LLE is then not in a position to actively or safely accept weight for control/support in standing. | |

Gait: | |

• LLE appears stiff, with insufficient hip and knee flexion during swing (appearance of increased tone/tension). | |

• Cadence is uneven, with stance time on left shorter than right. | |

• Step length is longer on the left. | |

• Trunk and shoulder girdles are asymmetrical, with left shoulder lower, and left arm hanging slightly more forward than right in standing. | |

• Trunk laterally flexed to left with left side of pelvis rotated back; weight shift asymmetrical, greater to right than left. | |

• Left toe drag is present approximately every fifth step. | |

• Base of support is wide and is related to left ankle inversion; ankle inversion worsens with weight shift to the right. | |

• Excessive lumbar flexion/extension is observed to occur at the points in the gait cycle and in the timing and sequencing pattern expected of hip flexion and extension; motion at the hip joint is less than expected. | |

• When left hip extension is facilitated during late stance, active resistance to the pattern of “shoulders back, hips forward” is felt; during these attempts to realign the trunk, the upper body resists realignment more than the pelvis/hip. | |

• When upper body initiation is prevented through handling, more effective hip extension can be facilitated, and better alignment of shoulders and hips over each foot during stepping can be obtained. | |

Additional information: | |

• Pelvis and lumbar spine are asymmetrical in sitting, with more lumbar extension on the right; pelvis slightly rotated back and tilted posteriorly on the left. | |

• In sitting, Dennis’s spine and rib cage are laterally flexed on the left; upper rib cage is flexed forward on the left; the scapula is tipped forward and downwardly rotated. • LLE spasms are strong enough to pop the night cast offalmost every night. |

Abbreviations: LLE, left lower extremity; LUE, left upper extremity; UE, upper extremity.

Table A6.3 Some of Dennis’s known and hypothesized integrities and impairments of individual systemsa

System | Integrities in individual systems | Impairments in individual systems |

Neuromotor | • Able to activate muscles throughout both sides of his body. • Relatively good isolated control in LUE. • Good control of right side of his body. | • Excessive coactivation in most activities; coactivation limits mobility in many areas. • Activation that is too strong for the movement or task—muscles are overfiring. • Imbalance of muscle activity for movement at specific joints (LLE > LUE); for example, ankle plantar flexion occurs, but with inversion; hip external rotation and abduction occur but with hip flexion; and hip internal rotation and adduction occur, but with hip extension. • Faulty timing and sequencing of muscle patterns for sit to and from stand, for ambulation, and for other movements. |

Musculoskeletal | • Can fairly effectively produce force against resistance in the LUE and LLE. • Strong right arm and leg. • No significant joint laxity. • Relatively good overall joint mobility and muscle length. • Relatively good alignment of joints of RUE and RLE; no history of arthritis or other joint pathology. | • Force production is varied, changes with position, and is more asymmetrical compared with the norm—i.e., adductors produce more force than abductors, plantar flexors produce more force than dorsiflexors. • Decreased muscle length in hamstrings (L more limited than R; medial more limited than lateral). • Muscle tightness limiting left hip flexion past 90° (more range is available if hip is allowed to externally rotate and abduct). • Muscle tightness that limits left hip extension with abduction on the left. • Tightness/shortness in muscles that externally rotate the tibia in a closed chain position (e.g., the medial hamstrings, ankle plantar flexors and calcaneal invertors such as tibialis posterior, and forefoot adductors), resulting in ROM limitations and resting posture of tibial external rotation, ankle plantar flexion, calcaneal inversion, and forefoot adduction. • Tightness/shortness of left pectoralis major and minor; malaligned left shoulder girdle. • Mildly limited and asymmetrical thoracic extension, L more limited than R. |

Sensory-perceptual | • Generally aware of both sides of his body, in spite of his moderate sensory deficit. | • Preexisting mild hearing loss. • Sensory deficit in LLE (touch, pressure, proprioception). |

Cognitive | • Able to understand and follow directions. | • Mild memory deficit. • Continued mild cognitive deficits for activities such as complex problem solving. |

Cardiovascular | • Is generally physically fit. • No significant endurance limitations. |

|

Abbreviations: L, left; LLE, left lower extremity; R, right; RLE, right lower extremity; ROM, range of motion; RUE, right upper extremity;

a As identified at the end of the evaluation session.

Table A6.4 Personal and environmental contextual factors relevant to Dennis’s recovery

Contextual factor | Facilitators | Barriers |

Personal | Motivated | Impatient at times |

Well educated | “If a little is good, more is better” attitude | |

Had history/experience during employment with activities that involved listening, negotiating | Tendency to overachieve | |

History of mild depression | ||

Retired | Tendency to focus on instructions for what to do, does not focus as well on precautions—what not to do | |

Had previous history of being active—walking, biking | History of working out; tends to prefer stretching activities versus movement/control activities | |

Had previously done yardwork and some housework, was willing to consider performing these tasks as part of therapy homework | ||

Has relatively good problem-solving ability | ||

Demonstrates good follow-through, use of compensatory strategies as needed (i.e., makes notes to remember things to tell therapist) | ||

Good family support, wife also retired and therefore available if assistance is needed | Weather and climate associated with living in the northern United States provide challenges to mobility | |

Adequate financial resources | Access to second floor in home is via steep stairs | |

Yardwork and snow removal are necessary during certain parts of the year |

At the initial evaluation, in answer to the questions posed to assess So what?, Dennis indicated an interest in returning to previous home and yard activities, interacting more actively with his grandchildren, resuming travel, and resuming a more active daily exercise and activity program. Knowledge of Dennis’s situation, assistance available at home, interests, and previous lifestyle helped Dennis and Marilyn to formulate goals that were meaningful and motivating.

A6.5 Intervention: Goals, Outcomes, Intervention Planning, Implementation, and Progress Over Time

At the completion of the initial evaluation session, goals and outcomes were set, an intervention plan was formulated, and initial intervention strategies were designed. Because the focus of this case report is the management of an individual client over a period of 5 years, discussion of outpatient intervention is divided into two phases:

• The early phase from 8 to 16 months poststroke.

• The later phase from 16 months to 5 years poststroke.

A6.5.1 Overview of Intervention

Dennis was seen in a facility for outpatient (OP) physical therapy during the period from March 2006 to March 2011, beginning ~8 months after his stroke. Intervention frequency was twice a week for 6 months, then once every 1 to 4 weeks for an 3 additional months. After that, Dennis was seen for specific problems and goals approximately once every 1 to 2 months for ~2 years, with the frequency varying, depending on the problems being addressed. He was not seen for almost a year, and then he was seen for two short episodes of care during the fifth year, each time with a specific purpose.

Throughout the early phase of intervention, requirements of Dennis’s insurance were addressed as needed, and at 12 months post onset, a formal appeal was made to the insurance company due to pending potential insurance denial. Additional therapy was approved following the appeal, and documentation continued as required by his insurance company and by Medicare, which covered the visits during part of the later phase of intervention.

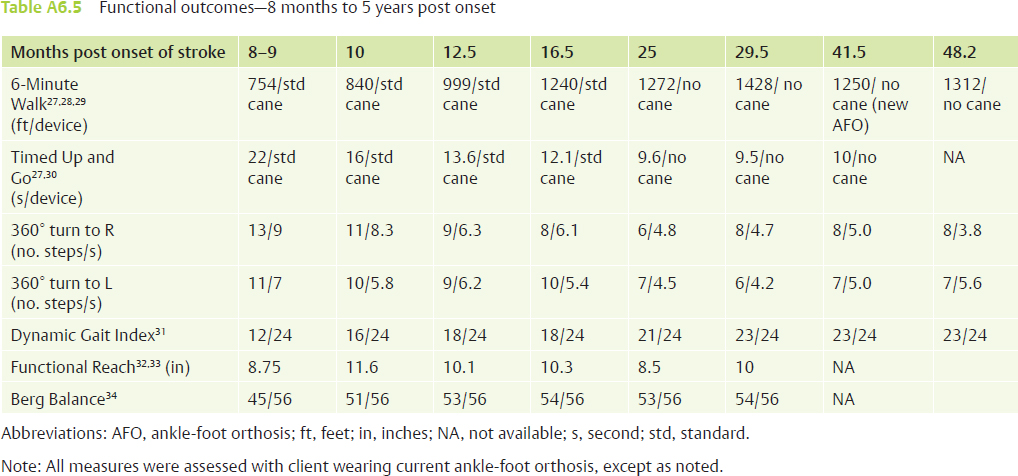

Dennis continued to make progress in functional mobility throughout the 5 years covered by this case report. An overview of his functional progress from 8 months to 5 years post onset, as measured via objective functional outcome measures, is presented in Table A6.5.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree