62 Sacrectomy

I. Key Points

– A posterior and combined approach to and instrumentation for total sacrectomy are feasible.

– Try to obtain wide margins and consider the use of intraoperative adjuvants (cryotherapy, phenol, brachytherapy, etc.).

– Use adjuvant radiation therapy (preferably intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) or proton beam) for contaminated margins.

II. Indications

– Aggressive benign tumors of the sacrum (giant cell tumors, osteoblastoma)

– Malignant primary sacral tumors (chordoma, Ewing’s sarcoma/ primitive neuroepithelial tumor [PNET], osteosarcoma, etc.)

– Selected cases of metastatic tumors/multiple myeloma (frequently located in the sacrum)

– Pelvic tumors invading sacroiliac joint and sacrum (chondrosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, osteosarcoma, etc.)

III. Technique

– Sacrectomy can be total or subtotal, a stand-alone operation or performed in the context of more complex sacropelvic resections (extended internal/external hemipelvectomies).

– Subtotal resections can be categorized according to the resection plane.

– Transverse/axial resection: usually done between sacral segments (S1/S2, S2/S3, below S3)

– Sagittal resection: can be in the midline (hemisacrectomy) or located more laterally (e.g., through or lateral to the neuroforamens)1,2

– Approach: depending on the location and tumor type, the approach could be posterior (longitudinal or transverse) or combined anteroposterior.

Posterior Approach

– It is generally accepted that sacrectomies at the S2/S3 level and not extending to the rectum can be performed via a posterior-only approach. For S1/S2 resections controversy exists; for total sacrectomies (L5-S1 level), most authorities recommend a combined approach, although there are reports describing total sacrectomy through a posterior approach alone.

– The type of posterior (transverse or longitudinal) incision may be indicated from a previous biopsy or from the tumor location. A longitudinal approach is typically employed, sometimes with a transverse component (T-type, Fig. 62.1): after the skin incision (with the biopsy tract incorporated), the gluteus maximus is dissected laterally and the erector spinae are detached from the midline and posterolateral aspect of the sacrum and flaps elevated in an upward fashion; this maneuver greatly facilitates surgical exposure.

– Subsequently, a laminectomy is done in the desired level and the cauda equina is ligated with double silk sutures and cut in the axilla of the most caudal nerve roots to be preserved (Fig. 62.2).

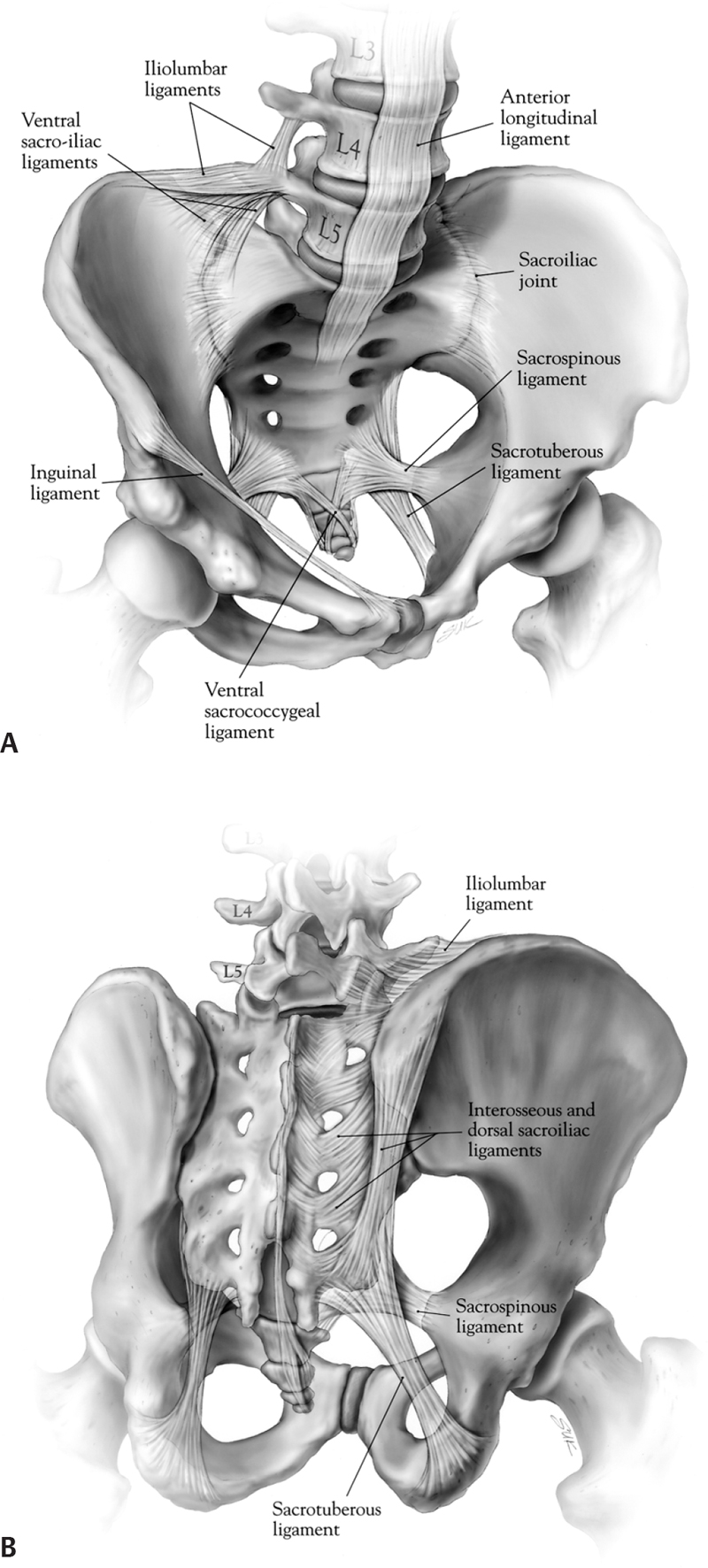

– The sacrum is freed from its attachment to surrounding structures (pelvic floor–anococcygeal ligament, sacrotuberous/sacrospinous ligaments, piriformis muscles). Piriformis resection should be as wide as possible as this has been found to decrease local recurrence.

– Finally, sacrectomy is completed using osteotomes; caution is recommended to the whole surgical team at this point because massive hemorrhage may commence.

Combined Approach (Anteroposterior)

– Typically, the anterior resection comes first. The surgery is preferably performed in a staged fashion (anterior → supine, posterior → prone) with an interval of 2 to 3 days between stages; this is believed to reduce morbidity. However, there are advocates of a single-stage operations either in the lateral position or in the supine/prone position.

– The anterior approach could be open, laparoscopic, intraperitoneal, or extraperitoneal. Involvement of the rectum makes the anterior intraperitoneal approach mandatory (typically by a general surgeon); if there is a clear plane between rectum and tumor, especially if the tumor is located eccentrically, a retroperitoneal approach may be used.1,2

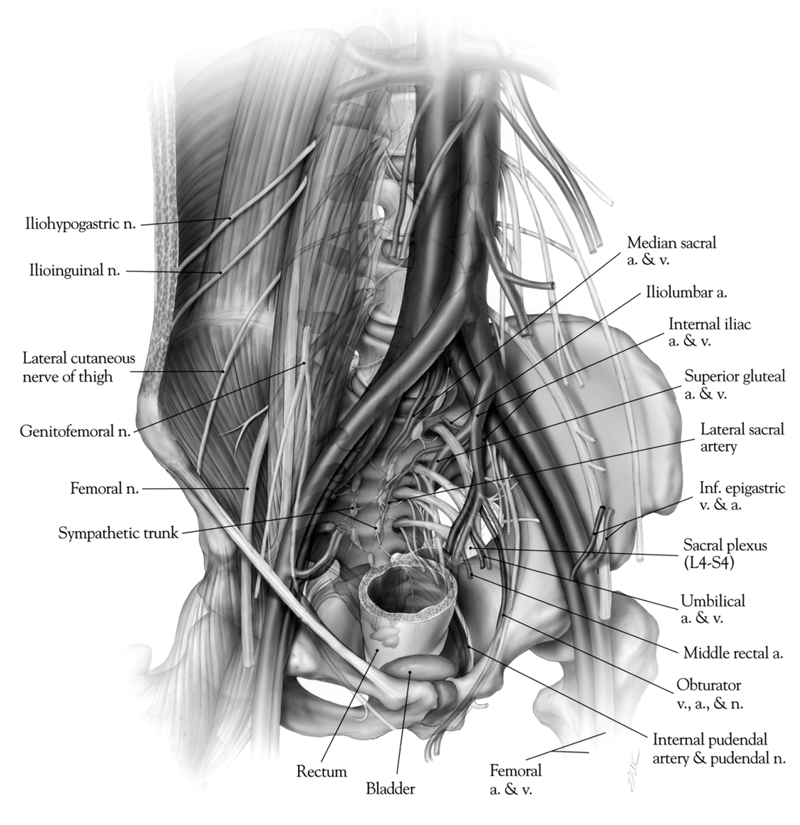

– At the end of the anterior stage, complete mobilization of the rectum is accomplished or a colostomy is performed; ligation of the internal iliac vessels is done with discectomy or osteotomy at the desired level and anterior osteotomy of the sacroiliac (SI) joints (or more laterally if needed). A radiopaque marker may be left at the discectomy/osteotomy level to facilitate localization at the second stage.

– It is widely believed that the use of a vertical rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap reduces the risk of wound infection/breakdown. This should be done at the first stage and the flap left in the wound to be utilized at the end of the posterior operation.

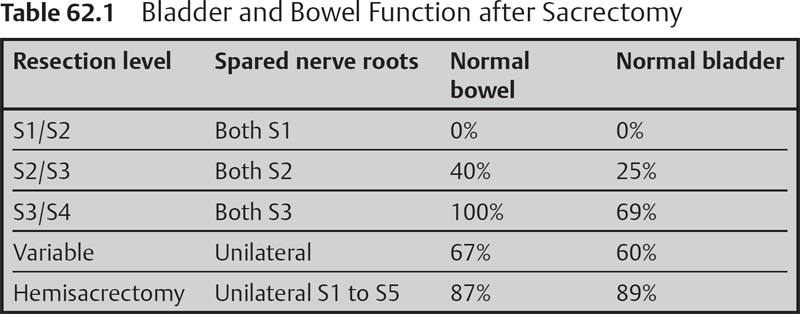

Fig. 62.1 Ligamentous anatomy of the lower lumbar spine, sacrum, and pelvis. (A) Ventral sacrum. (B) Dorsal sacrum. (From Dickman, Fehlings, Gokaslan, Spinal Cord and Spinal Column Tumors, Thieme; pg. 634, Fig. 44-1A,B.)

Fig. 62.2 Relationship of the ventral surface of the sacrum to the major pelvic structures, arteries, veins, and neural structures. (From Dickman, Fehlings, Gokaslan, Spinal Cord and Spinal Column Tumors, Thieme; pg. 635, Fig. 44-2.)

Reconstruction

– If the sacrectomy is performed below the S1/S2 level, reconstruction in general is not needed; however, a higher chance of sacral insufficiency fractures has been reported. Indications for instrumentation include total sacrectomy, partial sacrectomy involving more than 50% of SI joints, or sagittal hemisacrectomy that obliterates the SI joint unilaterally or bilaterally. However, even for total sacrectomies, some authorities believe that any stabilization is unwarranted, since this typically prolongs the operation and increases morbidity and risk of infection. Total sacrectomy is believed to create a flail axial skeleton, leading to pain or mechanical kinking of neurovascular structures or viscera and significantly affecting ambulation, a set of conditions favoring reconstruction.

– Reconstruction began in the 1980s with Harrington rods, moved to the Galveston-Luque wire technique in the 1990s, and now consists of a two-to-four-rod construct interconnected with sacral bars; pedicle screws are placed from L2-L3 caudally and the pelvis is anchored with long iliac screws (two to four).

– Cortical strut grafts (e.g., fibular or femoral diaphysis) can be used to bridge the osseous gap between the SI joints or iliac wings. They provide a more biologic fixation and the ability to form an osseous bridge and maintain continuity with the disrupted ring. This may prove very important in long-term survivors.1,2

– A newer and more technically challenging technique has been described by the Mayo group. Two fibular grafts are placed between L5 and the supra-acetabular region bilaterally along the force transmission lines, providing triangulation and increasing resistance to failure by two times.3 Experience indicates that it may be easier to insert the strut grafts in the posterior inferior iliac spine.

IV. Complications

– Hemorrhage (injury of internal iliac, iliolumbar, and median sacral vessels, eg), which may be life threatening

– Visceral damage (rectum, ureters)

– Wound healing problems/infection (may be as high as 50%)

– Sensorimotor, bowel, bladder, and sexual dysfunction. The higher the resection level, the greater the morbidity. As a general rule, preservation of at least one S3 nerve leads to the preservation of function in two-thirds of patients, unilateral sacrectomy has good results in 90%, and S1/S2 resections or total sacrectomies result universally in loss of function (Table 62.1).4 Saddle anesthesia is common; motor loss is encountered only in cases of S1 root resection.

– Sacral insufficiency fractures

– General medical complications (pneumonia, ileus, deep vein thrombosis (DVT), etc.). Generally, the morbidity and mortality are high (5% perioperative deaths in Sloan Kettering series).5

V. Postoperative Care

– Stabilization of the patient is crucial in the first postoperative days (typically in the intensive care unit).

– Ambulation may be commenced immediately for low resections, or in a delayed fashion, depending on the level of stability and fixation quality, with walking aids.

– Keep wound clean, with frequent dressing changes to prevent contamination from rectum.

– Give stool softeners and high-volume food supplements. Patients may need to manually disimpact stools. Gradually attempt bladder training, with the possible need for patients to self-catheterize.

VI. Outcomes

– Survival is greatly dependent on the type of the tumor, previous operations, and tumor location. For sacral chordomas, which are the most common tumors warranting sacrectomy, 5-year and 10-year survival are 68% and 40%, respectively (SEER database). Local recurrence occurs in about 40% (28% for wide versus 64% for intralesional in one series of 64 chordomas). Distant metastasis occurs in one-third of patients.5

VII. Surgical Pearls

– The posterior-only approach is useful for S1/S2 resections and the combined anteroposterior approach (in a staged fashion) is practiced for higher resections.

– Use of the rectus abdominis flap in combined procedures reduces wound complications.

– Anticipate and prepare the surgical team for blood loss when initiating a posterior osteotomy (ensure good hydration, give aminocaproic acid, make PRBCs and FFPs available).

– For total sacrectomies use a two- (or four-) rod construct with interconnecting sacral bars. Strut allografts (either transverse or in a triangular fashion) are desirable to promote fusion.

– Wide resection is crucial to prevent local recurrence and significantly affects survival. Try to obtain negative margins in the sacrospinal canal and wide surgical margins posteriorly, by excising parts of the piriformis, gluteus maximus, and sacroiliac joints.

Common Clinical Questions

1. Which nerve roots are critical for bladder/bowel function and should be preserved if possible?

2. What is the incidence of local recurrence after wide and intralesional resection of sacral chordomas? Does it affect survival?

3. Which level of resection can be performed safely via a posterior approach only, and when is a combined approach mandated?

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree