CHAPTER 63 Selective Amygdalohippocampectomy

Historical Considerations

Over the course of the past century, two main factors have driven the surgical approach to epilepsy. First, an appreciation of the central role of the mesial basal temporal structures in many cases of human epilepsy has been gained from clinical observation and neuropathologic, electrophysiologic, and radiologic studies.1 Second and in parallel has been accumulating evidence from numerous surgical series demonstrating that temporal lobe resection, in particular, resection of mesial temporal structures, leads to an 80% to 90% rate of freedom from seizures in patients with medically intractable temporal lobe epilepsy.1–7

A number of surgical techniques have evolved in the process. The standard temporal resection procedure has been en bloc anterior temporal lobectomy (ATL) involving anterior neocortical resection of up to 4.5 to 6.5 cm, depending on whether the dominant temporal lobe is being operated on, and mesial temporal resection encompassing the amygdala and at least 3 cm of hippocampus. This approach was originally advocated by Falconer and colleagues in 19558 and is still used today.

Selective surgical approaches to the amygdala and hippocampus evolved as evidence increasingly indicated a critical role for these structures in epileptogenesis, and methods were sought to minimize collateral surgical injury to important temporal neocortical structures. Niemeyer was the first to describe selective transcortical transventricular amygdalohippocampectomy (STTAH) in 1958.9 A direct approach to the mesial temporal structures via the middle temporal gyrus was used, an approach that Olivier would later refine with the assistance of frameless stereotaxy.1

Other surgeons have approached the mesial temporal structures via less direct paths. Weiser, Yasargil, and their coworkers reported a transsylvian approach to the medial temporal structures that had the theoretical advantage of complete avoidance of neocortical injury; however, the approach was technically more demanding and placed critical vascular structures at risk.10,11 Hori and associates described a subtemporal selective approach and reported fewer neuropsychological sequelae as an advantage.12,13

With the recent confirmation that temporal lobectomy is superior to the best medical therapy for patients with intractable temporal lobe epilepsy,7 focus has now shifted toward understanding what is the best surgical approach to achieve this end. Selective amygdalohippocampectomy (SAH) represents an approach to the mesiobasal temporal structures that is as effective as ATL in selected patients, has the potential to minimize neocortical injury and its neurological sequelae, and is an approach that may be used by most neurosurgeons.

Surgical Rationale for Selective Amygdalohippocampectomy

Seizure outcome after epilepsy surgery has been noted to depend largely on diagnostic and clinical variables that have an impact on patient selection.3,6 The efficacy of selective approaches versus traditional en bloc ATL with mesial resection for seizure control has been examined in a number of noncontrolled series and found to be comparable in most,3,5 but not all reports,2 and this variability may reflect differences in the types of patients selected for surgery. Indeed, even in studies that have claimed the highest rates of freedom from seizures with the selective approach,1 it is evident that strict attention to preoperative selection is important.

In the absence of surgical complications such as stroke or infection, neuropsychological complications, particularly memory loss, are the major potential morbidity after all temporal resections. It is argued that these complications must arise from resection of functioning normal tissue and are therefore less likely to occur in patients undergoing more selective resection. Although confounding variables such as the dominance of the resected side, the absence of ipsilateral hippocampal sclerosis, the focality of the epileptic source, the presence of intact memory, and methodologic differences in neuropsychological testing make direct comparisons difficult, there is accumulating evidence that individually tailored or selective approaches may have a more favorable cognitive outcome than standard resections3,5,14,15; however, not all studies have shown such results.

Preoperative Evaluation and Decision Making

Patients under consideration for epilepsy surgery have medically refractory epilepsy. Although the definition of medical intractability may vary, data from Kwan and Brodie and from others suggest that these patients can be identified early, perhaps after as few as two failed trials of antiepileptic drugs.16

Clinically significant postoperative memory loss is more likely in patients with left (dominant) temporal lobe epilepsy, intact preoperative verbal memory, normal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) results, bilateral hippocampal abnormalities, and later age at seizure onset.3,17 Assessment of these factors guides preoperative counseling regarding the risk for postoperative memory deficits. These risks are tempered by the hazards associated with not operating (some patients with medically treated refractory temporal lobe epilepsy have accelerated memory loss) and by the knowledge that some cognitive skills can stabilize or improve after successful surgery.

Selective Transcortical Transventricular Amygdalohippocampectomy—Operative Procedure and Avoidance of Complications

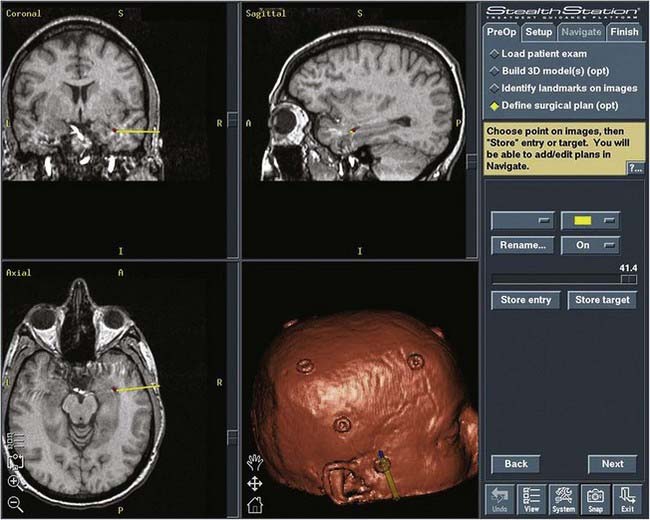

All patients undergo preoperative stereotactic brain MRI with fiducial scalp markers in place. Images are transferred to a Stealth Workstation (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN), and the surgical entry point and trajectory are planned so that the most direct route is taken to the ipsilateral temporal horn from the middle temporal gyrus, approximately 3 cm from the tip of the temporal lobe (Fig. 63-1).

FIGURE 63-1 Image from the Stealth Workstation showing the plan for the entry point and trajectory to the temporal horn.

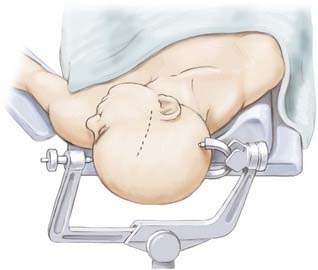

The patient undergoes routine general anesthesia and endotracheal intubation with insertion of a urinary catheter and administration of antibiotics. Mannitol is not used routinely. The patient is positioned supine with the head rotated 90 degrees to the opposite side, parallel to the floor with the head held in a three-pin fixateur. Attention to level positioning of the head is important to achieve a true lateral trajectory. Fiducials are registered and the planned cortical entry point marked on the scalp along with the intended bone flap and scalp incision (Fig. 63-2). The scalp is then prepared, draped, and infiltrated with 1% lidocaine and a 0.25% bupivacaine mixture with epinephrine.

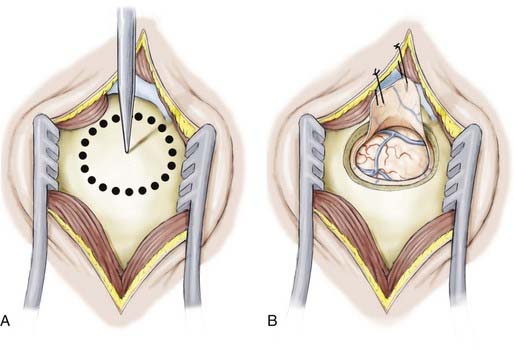

The linear scalp incision is opened, the temporalis fascia sharply incised, and the longitudinal fibers of the temporalis dissected from the periosteum and retracted laterally. The neuronavigation system is then used to direct the position of the temporal craniotomy, which invariably reaches the floor of the middle cranial fossa. After the dura is exposed and the surface vessels controlled with diathermy, the dura is opened and reflected inferiorly (Fig. 63-3).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree