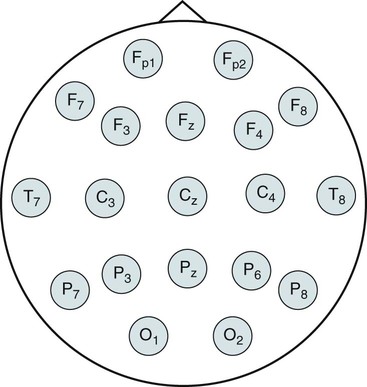

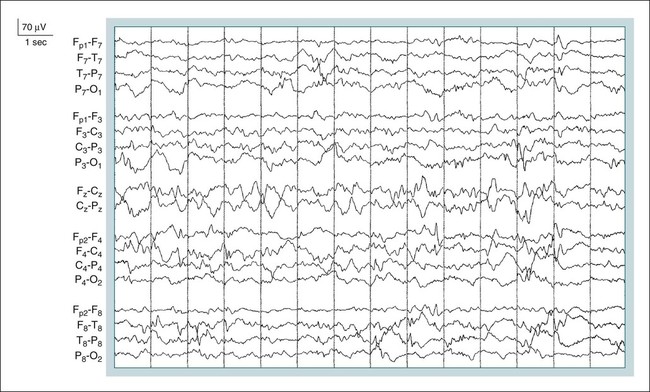

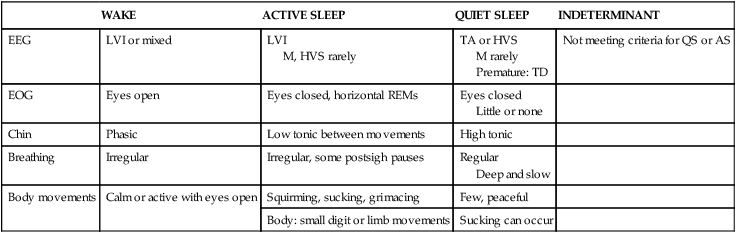

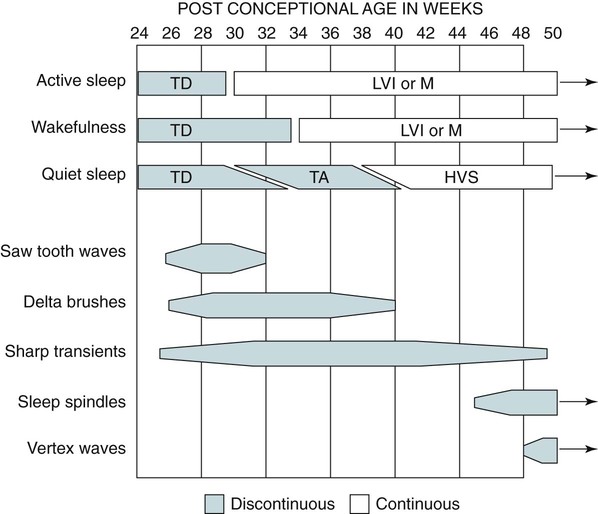

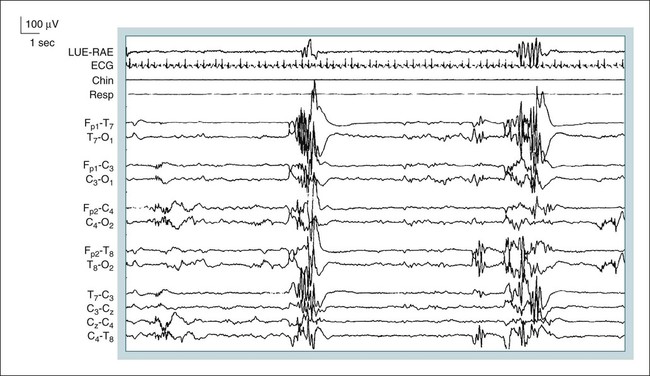

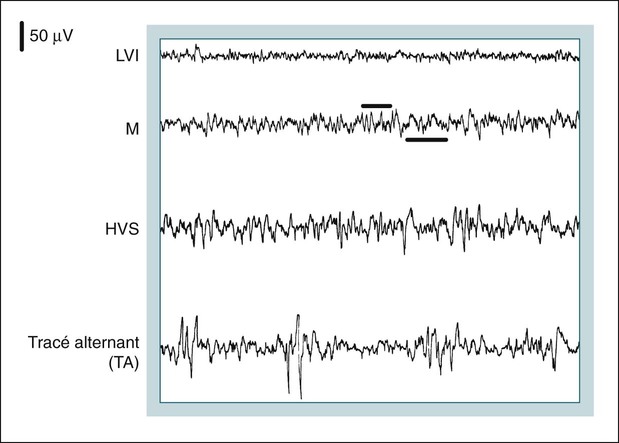

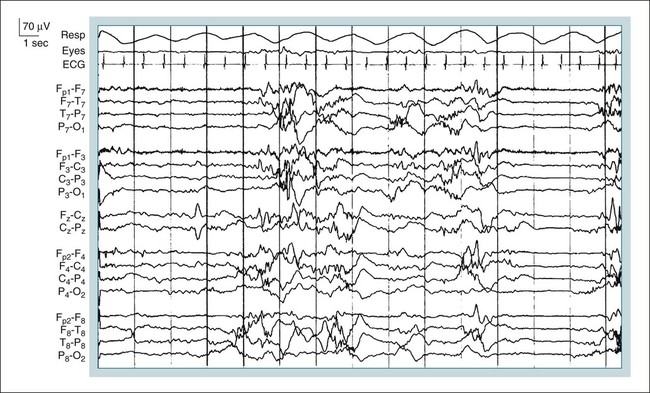

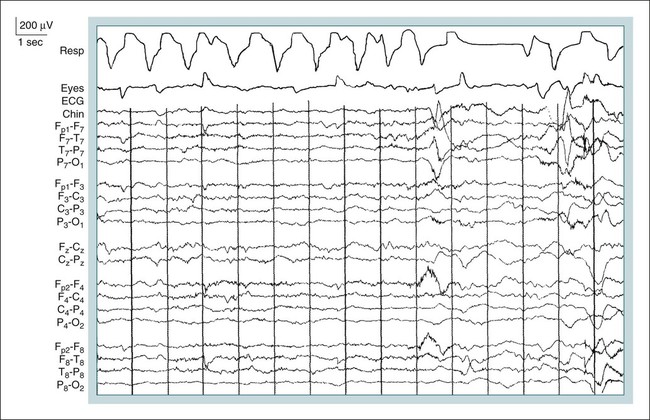

• For infants younger than 2 months of age (48 wk CA—time since conception), sleep may be staged according to the rules of Anders, Emde, and Parmelee. • Sleep staging in infants depends on behavioral observations because wake and sleep may have similar EEG patterns. • In infants, AS corresponds to stage R and QS to NREM sleep. • In term infants, entry to sleep via AS is the norm and AS composes about 50% of sleep. • Timing of appearance of characteristic EEG patterns of sleep (age postterm): • By age 6 months, stages N1, N2, and N3 can usually be scored (sometimes younger). • The DPR is the dominant rhythm over the occipital regions in relaxed wakefulness with eyes closed. DPR is attenuated by eye opening. • The frequency of the DPR increases with age. The frequency of DPR increases from around 4 Hz at 4 months to 8 Hz by age 8 years in most individuals (adult range 8–13 Hz). • Unique EEG patterns that are used to identify stage N1 in children include rhythmic anterior theta (5–7 Hz over frontal derivation) and hypnagogic hypersynchrony (high-voltage 3–4.5 Hz activity), maximal in frontal and central derivations. The American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) scoring manual1,2 provides new scoring rules for infants older than 2 months and children. However, previously, the terminology for sleep staging for the newborn infant used different terminology, and sleep was staged according to the sleep scoring rules of Anders, Emde, and Parmelee.3 These have been widely used for infants in the past and can still be used for scoring sleep in infants younger than 2 months of age. The gestational age is the time from conception to birth (estimated from last menstrual period). The conceptional age (CA) is gestational age + time in weeks since birth. If one assumes term means 40 weeks, then the AASM rules would apply at 48 weeks’ CA. For an infant born at 36 weeks, the AASM rules would apply at age 3 months (CA 48 wk). In some of the tracings to follow, bipolar electroencephalogram (EEG) montages are illustrated using frontal (F3, F4, F7, and F8), central (C3 and C4), parietal (P3, P4, P7, and P8), and occipital (O1 and O2) electrodes (Fig. 5–1). Some of these electrodes are used in standard sleep recording and others are not. Clinical EEG is discussed in detail in Chapter 27. However, for reference, EEG electrode positions are illustrated in Figure 5–1. Infant sleep is divided into active sleep (AS; corresponding to rapid eye movement [REM] sleep), quiet sleep (QS; corresponding to non–rapid eye movement [NREM] sleep) and indeterminant sleep, which is often a transitional sleep stage. Unlike adults, infants transition from wake to sleep via AS. The characteristics of each stage are listed in Table 5–1: The EEG patterns associated with wake, QS, and AS are discussed later.1–6 The sleep of premature infants differs from that of term infants (CA 38–40 wks). The timing of the appearance of different EEG patterns characteristic of different sleep stages is illustrated in Figure 5–2. Behavioral observations are essential for sleep staging because EEG patterns may be associated with more than one state. TABLE 5–1 Characteristics of Sleep Stages in Term Infants3 The EEG patterns of sleep in the pre-term and term infant are3 1. Tracé discontinue (TD): A discontinuous pattern consisting of high-voltage bursts with sharp features separated by long, dramatically flat EEG periods of 10 to 20 seconds (Fig. 5–3). TD is seen at or before 30 weeks CA (see Fig. 5–2) and is the EEG pattern of QS in that age group. 2. Tracé alternant (TA): A discontinuous pattern (Figs. 5–4 and 5–5) that characterizes the QS of newborns after about 30 weeks CA (see Fig. 5–2). Bursts of mixed activity of 2 to 8 seconds are interspersed with periods of flatter EEG. The bursts are composed of high-voltage slow waves superimposed with rapid low-voltage sharp waves. There is a continuum between TD and TA, but in general, in TA, the high and low periods have fairly equal durations and the bursts do not have full bilateral synchrony. In TD, the flat is very flat and the bursts are very high voltage and have synchrony. 3. Low-voltage irregular (LVI): Continuous low-voltage mixed-frequency with prominent delta and theta rhythms and little variation. Voltage (14–35 µV), theta rhythm predominates (see Fig. 5–4). 4. High-voltage slow (HVS) pattern: Continuous, irregular mixed frequencies with higher voltages (50–100 µV) and more prominent delta frequencies (see Fig. 5–4). 5. Mixed pattern (M): Similar to LVI but with slightly higher voltages and more delta activity. Mixture of HVS and low-voltage polyrhythmic activity (see Fig. 5–4). In premature infants with a CA less than 30 weeks, QS usually shows a pattern of TD.3,4 The pattern of TD is characterized by electrical quiescence between bursts of high-voltage activity. In contrast, TA is characterized by a lesser reduction in amplitude between periods of higher-amplitude activity. Another difference between TA and TD is that delta brushes (fast waves of 10–20 Hz) are superimposed on the delta waves in TD. As the infant matures, delta brushes disappear and the TA pattern replaces TD. Finally, at term, the EEG of QS is characterized by an HVS pattern. The EEG of AS in premature infants younger than 30 weeks may also show TD but later is typically LVI or M. The EEG pattern of wake and sleep is similar and states are distinguished by sustained eye closure (sleep) and open eyes (wake). AS is characterized by grimacing, sucking, an LVI EEG pattern, REMs, and low electromyogram (EMG) activity (Fig. 5–6; see also Table 5–1). Breathing is irregular in AS. QS (Fig. 5–7) is characterized by a peaceful infant with non-nutritive sucking and regular deep respiration. The EEG may show TA at early ages and HVS later. No or few eye movements are noted and the chin EMG is tonic and high. After about 3 months, the percentage of REM sleep starts to diminish and the intensity of body movements during AS (REM) begin to decrease. The pattern of NREM at sleep onset begins to emerge. However, the sleep cycle period does not reach the adult value of 90 to 100 minutes until adolescence.7–12 As children mature, more typical adult EEG patterns begin to appear. The time of appearance is somewhat variable, but the values in Table 5–2 are typical. Sleep architecture in children is discussed in more detail inChapter 6. TABLE 5-2 Age of Onset of Electroencephalographic Patterns

Sleep Staging in Infants and Children

Bipolar Electroencephogram Recording

Sleep in the Premature Infant and Infants Younger Than 48 Weeks CA

Sleep Stages in the Newborn

WAKE

ACTIVE SLEEP

QUIET SLEEP

INDETERMINANT

EEG

LVI or mixed

LVI

M, HVS rarely

TA or HVS

M rarely

Premature: TD

Not meeting criteria for QS or AS

EOG

Eyes open

Eyes closed, horizontal REMs

Eyes closed

Little or none

Chin

Phasic

Low tonic between movements

High tonic

Breathing

Irregular

Irregular, some postsigh pauses

Regular

Deep and slow

Body movements

Calm or active with eyes open

Squirming, sucking, grimacing

Few, peaceful

Body: small digit or limb movements

Sucking can occur

EEG Patterns

Premature Infants

Term Infants

Sleep Architecture

WAVE FORM

DESCRIPTION

AGE FIRST SEEN

Sleep spindles

12–16 Hz

2–3 mo

K complexes

Biphasic initial neg (up)

4–6 mo

Deflection

Slow wave activity

>75 µV p-p in frontal derivation

4–5 mo postterm

Frequency 0.5–2 Hz ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Sleep Staging in Infants and Children