CHAPTER 281 Spondyloarthropathies (Including Ankylosing Spondylitis)

The spondyloarthropathies have an association with the major histocompatibility complex antigen HLA-B27, which presents microbial antigens to T lymphocytes. There is a racial variation in disease that parallels the variation in HLA-B27. In the general population, about 8% of white individuals, 4% of Africans, 8% of Chinese, and 1% of Japanese possess the HLA-B27 antigen.1 It is also more prevalent in the northern latitudes. In northern Scandinavia, for instance, 24% of people are HLA-B27 positive, and 1.8% are affected by AS.

Subtypes of HLA-B27 have been identified, some of which are positively associated with disease but others are negatively associated.2

Major Types of Spondyloarthropathy

Ankylosing Spondylitis

AS represents the prototypical spondyloarthropathy and is the most commonly seen of the group in the practice of a spine surgeon. Derived from Greek, the name refers to an inflammatory condition of the spine (spondylos) resulting in stiffening and angulation (angkylos).3 Besides being a source of disabling pain in both the axial and appendicular skeleton, it is a cause of major spinal deformity that often requires surgical attention.

The overall incidence of AS in the United States is 0.1% to 0.2%. Even though men are more commonly affected (3 : 1 ratio), women carry a higher risk of having an affected child.4 This pattern is also seen in inflammatory bowel disease. However, evidence does not suggest a worse prognosis or greater severity of disease in the children of affected women.5

Significant dysfunction and progressive disability are the norm, although a large percentage of patients are able to maintain employment and productivity. After a decade of disease, a clinically significant sagittal plane deformity will develop in approximately half of the patients with AS.6 Nevertheless, disability increases with disease severity, as do costs associated with advancing disease.7 Patients with AS are more likely to have never been married, more likely to be divorced, and more than twice as likely to be work-disabled than members of the general population. As would be expected, individuals with physically demanding occupations and lower educational status are at greater risk for work disability.8 Women with AS are also less likely to have had children than women in the general population.9

Psoriatic Arthritis

Genetic, environmental, and immunologic factors are believed to play a role in the development of this disease, although the specific etiology is not well understood. At least 40% of patients with psoriasis are found to have radiographic evidence of inflammatory arthritis,8 and significant disability may develop in patients with psoriatic arthritis, with up to 20% demonstrating a rapidly progressive, debilitating clinical course.10 Psoriatic arthritis is a clinical diagnosis and involves the findings of inflammatory arthropathy and psoriatic skin lesions.11 See Table 281-2 for discussion regarding the clinical features of inflammatory back pain and arthritis.

Psoriatic arthritis may be associated with obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and insulin resistance because of the shared inflammatory pathway.12

Pathophysiology

The underlying inflammatory process involves T cells and cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α).13,14 Matrix metalloproteinase-3 (MMP-3) is an enzyme thought to be related to pathogenesis and is also used as a disease marker.15 AS has been found in association with conditions such as multiple sclerosis, thus raising the possibility of a common pathway to disease.16

Although the link between infection and arthritic disease is most clear in reactive arthritis, a link is suggested in the other spondyloarthropathies as well. Klebsiella IgG is found in increased levels in patients with AS.17

Muscle biopsy studies in patients with AS show evidence of abnormal, atrophied types I and II muscle fibers.18 Whether this contributes to the development of disease or is a result of the disease itself is unclear.

HLA-B27–restricted T cells have been implicated in the development of reactive arthritis as a response to bacterial infections. The HLA-B27 gene is strongly associated with the conditions, but it has a variable association with each subtype. Its strongest link is in white male patients with AS, in whom it is found 90% of the time. The prevalence of the gene is 8% in the general white population and 4% in the African American population. It is more common in regions further from the equator.19

AS develops in approximately 1% to 2% of people with HLA-B27. This risk increases to approximately 20% to 30% when a first-degree relative carries the diagnosis.20 It is likely that AS is actually more common than has been reported to date.

Overproduction of bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2) and BMP-7 has been noted in patients with AS, and serum BMP-7 levels can reflect radiographic damage.21 The processes leading to bone fusion and the links between inflammation and bone formation remain poorly defined.22 Current research into further susceptibility genes and inflammatory mediators provides hope for greater understanding and treatment options. HLA-60 is another susceptibility gene that may have a role.

Clinical Findings and Diagnosis

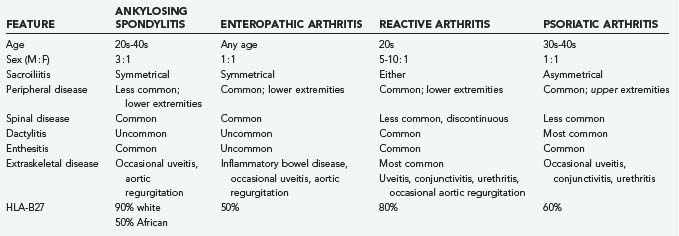

The spondyloarthropathies have somewhat variable clinical findings, depending on the subtype. Table 281-1 outlines some of these variations. In general, AS tends to be seen in the younger male population.

A combination of history and findings on physical examination, along with imaging and laboratory tests, is used in the diagnosis of these conditions. Although advanced disease may have obvious hallmarks, early disease may be subtle. Multiple validated systems have thus been developed to assist in the stepwise analysis of patients, such as the European Spondyloarthropathy Study Group (ESSG) criteria (Table 281-2) and the Amor criteria. The Modified New York criteria (Table 281-3) and the Rome criteria are used specifically for the diagnosis of AS. Although the ESSG criteria have been found to be the most sensitive for spondyloarthropathy and inflammatory back pain, the Modified New York criteria are the most specific for AS.23 Patients are evaluated for features of inflammatory back pain, as opposed to mechanical back pain (which may be acute in onset or associated with activity and radicular symptoms). The most specific symptoms include pain during the second half of the night, early morning stiffness lasting 30 minutes, alternating buttock pain (referred from the SI joints), and improvement with exercise, not rest (Table 281-4).

TABLE 281-2 European Spondyloarthropathy Study Group Criteria for Spondyloarthropathies

TABLE 281-3 Modified New York Criteria for Ankylosing Spondylitis

TABLE 281-4 Inflammatory versus Mechanical Back Pain

| FEATURE | INFLAMMATORY | MECHANICAL |

|---|---|---|

| Night pain | + | − |

| Morning stiffness | + | − |

| Sacroiliac referred buttock pain | + | ± |

| Radicular pain | − | + |

| Improves with | Activity | Rest |

Appendicular skeletal disease is associated with peripheral joint involvement, most commonly in the hips and shoulders. Patients with kyphosis attempt to restore sagittal balance through hip extension, knee flexion, and ankle plantar flexion.24 Having said this, hip flexion contractures by and of themselves can be a significant source of sagittal postural imbalance. As a hip flexion contracture develops, patients adopt a forward-flexed posture that may exaggerate the appearance of the kyphosis. Evaluation of the hips is crucial in arriving at an accurate assessment of the degree of spinal deformity that may be present.

Extraskeletal disease involves multiple organ systems, with each subtype of spondyloarthropathy having a somewhat different predilection for each. Such disease includes cardiovascular disease, more specifically aortic insufficiency and conduction disturbances; pulmonary disease, such as apical pulmonary fibrosis; deposition disease, such as amyloidosis with its associated renal dysfunction; and neurological disease such as encephalitis, transverse myelitis, and peripheral neuropathy.25

Neurological deficits may arise as a result of spinal stenosis, upper cervical instability, and chronic inflammation. Ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (PLL) in association with AS has been noted and contributes to the acquired stenosis. Because the upper cervical spine tends to lag behind in bony ankylosis, compensatory hypermobility may develop and result in neurological complications. Cauda equina syndrome may be seen, perhaps as a result of chronic inflammation, demyelination, and fibrosis, along with the development of arachnoid diverticula.26

Imaging

Characteristic findings are noted on radiographic imaging, and the extent of such findings has been found to correlate clinically with patient spinal mobility and function.27,28

One of the hallmarks of AS is the “bamboo spine” (Fig. 281-1). As marginal syndesmophytes form along the intervertebral disks, the spine takes on the appearance of a single long bone (contributing to the loss of flexibility and increased risk for fracture). Marginal syndesmophytes are differentiated from (1) osteophytes, which do not typically bridge the disk space, and (2) nonmarginal syndesmophytes, which extend beyond the margin of the disk and spinal column, as seen in diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis. “Squaring” of the vertebral bodies occurs as the end plates lose their concavity, probably related to chronic inflammation. These spinal changes typically begin distally within the lumbar spine and progress slowly cephalad.

SI fusion is another hallmark and is required for diagnosis by the New York criteria (Fig. 281-2). It is typically observed before other radiographic changes. Earlier in the disease, erosions are noted at the lower end of the joint, especially over the iliac side. Erosive changes may be seen at the symphysis pubis (osteitis pubis). As ossification progresses along entheses such as the iliac crests, ischial tuberosities, and femoral trochanters, a process known as “whiskering” is observed.

Spondylodiskitis is characterized by an inflammatory, erosive process of the intervertebral disk, commonly at the thoracolumbar junction. It is unknown whether this erosion represents an area of persistent inflammation, failure of ankylosis across an area of high mechanical stress, or an area of nonunion after trauma to the already ankylosed spine.29 Approximately 5% of patients with AS have been shown to have spondylodiskitis, but only half of these patients tend to be symptomatic.30 Radiographically, spondylodiskitis appears similar to chronic infectious diskitis, with end-plate erosion and surrounding bony sclerosis. Frequently, anterior widening of the disk space is noted.

Enteropathic arthritis has radiographic features similar to those of AS. In contrast, Reiter’s syndrome and psoriatic arthritis typically result in noncontinuous spondylitis, nonmarginal syndesmophytes, and asymmetrical SI joint involvement.1

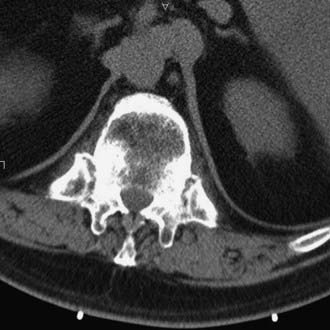

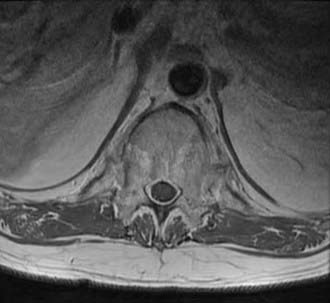

Computed tomography (CT) shows similar changes but in greater bony detail. Extensive changes may be noted at the costovertebral articulations (Fig. 281-3). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may show marrow signal alterations secondary to chronic inflammation in this region (Fig. 281-4).31,32

Ossification of the PLL has been observed in association with increasing age and has variable ethnic prevalence.33

Radiologic methodologies for assessing the extent of spinal involvement have been proposed and are in use.34–36 These methods have been helpful in assessing the efficacy of treatment regimens in both the research and clinical fields, which was previously hampered by an inability to objectively gauge a patient’s progress. Such instruments include the Stoke Ankylosing Spondylitis Spine Score (SASSS) and the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Radiology Index (BASRI).

Methods specific to enthesitis that focus on the ligamentous and muscular insertions at the level of the Achilles tendon, femur, and humerus have been used.37

Peripheral joint involvement is seen most commonly in the hips and shoulders.

Bone mineral density is reduced because of a tremendous loss of trabecular bone. This is noted on plain x-ray imaging studies, but dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry may show a paradoxical increase in density as a result of enthesopathy and greater peripheral bone formation.38

Primary Management

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are used extensively for inflammatory and rheumatic disorders such as the spondyloarthropathies.39 Recent evidence suggests that NSAIDs not only treat the symptoms of inflammatory polyarthropathy but may also have more of a “disease-modifying” role by retarding radiographic progression and symptoms of arthritis.40 Celecoxib, indomethacin, naproxen, and phenylbutazone are among such medications that have specifically been used for the treatment of AS.41–44 To avoid complications associated with long-term use, medication use may be decreased during periods of relative disease inactivity.

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) have opened up a new avenue for treatment, and work continues to be done in the pharmacology arena.45 There are several regularly used drugs that have various mechanisms of action. Sulfasalazine and methotrexate have a history of effective use in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and are used for treatment of the spondyloarthropathies as well. Nevertheless, their efficacy in treating axial spinal pathology such as seen in the spondyloarthropathies is relatively limited.46,47

Other DMARDs include adalimumab, etanercept, and infliximab. These drugs are examples of TNF-α inhibitors48–50 and are recombinant TNF-α receptors that bind the molecule in serum, thereby preventing systemic activity.51 They have been found to exert a beneficial effect on articular cartilage inasmuch as a decrease in serum markers of cartilage degradation has been observed.52 Intra-articular injection of anti-TNF agents has also been described.53 These agents may be used in combination with other medications, such as methotrexate. However, the risk for serious infection increases significantly with such therapy. Widespread use of these drugs is limited somewhat by cost54,55 and concerns regarding long-term use.56,57

The response to treatment with drugs may be monitored by following serum levels of acute-phase reactants such as the erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, MMP-3,58 and various cytokines.59,60 Serum markers of bone and cartilage degradation and synthesis are also useful in this manner and are thought to be related not only to cartilage and collagen turnover but also to new bone formation through endochondral ossification, as occurs in the spine of patients with AS.61

In the case of psoriatic arthritis, TNF-α antagonists are used for both skin and joint disease, whereas efalizumab, which targets T lymphocytes, is indicated only for the skin disease.62–65

Exercise therapy is considered helpful in maintaining patient function, and there is evidence of a direct biologic effect of such therapy. Patients who regularly perform back exercises and have appropriate social support have been shown to have a greater degree of function.66 Exercises focus on strengthening of the spinal extensor muscles and maintenance of peripheral joint mobility. However, there is a need for a standardized approach to complement medical therapy.67

Tobacco abuse is also associated with poor function.53 Discontinuation of tobacco and nicotine products is thus critical not only for surgical patients but also for improved disease management in any patient with AS.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree