Figure 5.1 Circle of Willis. Angiogram of circle of Willis (COW). Normal (right).

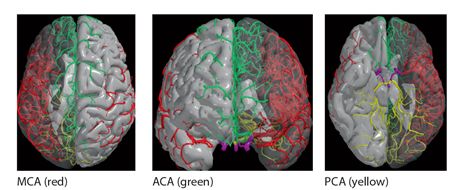

Figure 5.2 Territories supplied by main cerebral arteries

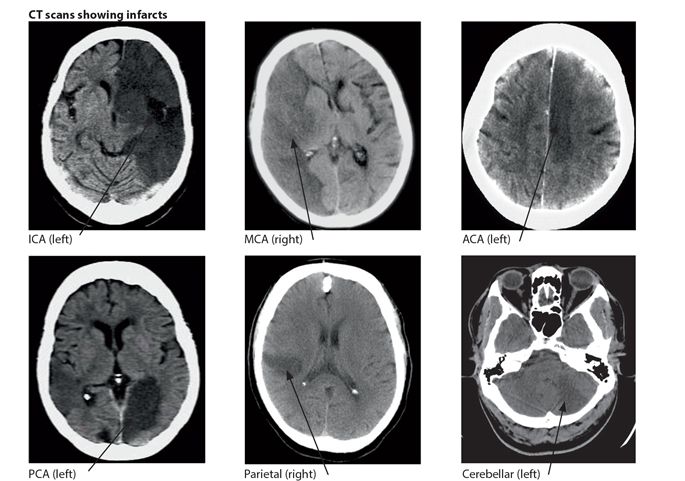

Figure 5.3 Infarction in territories of the main cerebral arteries

Haemorrhage

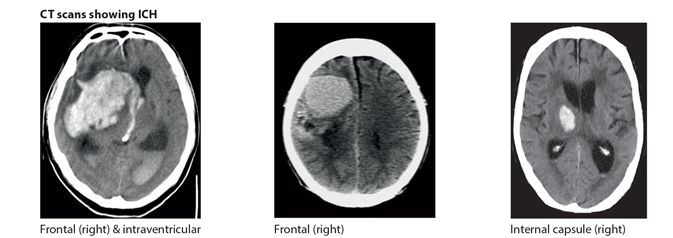

About 10-20% of strokes worldwide are caused by haemorrhage. This percentage is higher in Africa (20-40%) probably because of the high burden of untreated or inadequately treated hypertension. Haemorrhagic stroke occurs when there is sudden release of blood into the brain. The main types are intracerebral haemorrhage (ICH) and subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) (Figs. 5.4 & 6). Hypertension is the major cause of ICH and is also a risk factor for SAH. The sources of bleeding in chronic hypertension are ruptured Charcot-Bouchard micro aneurysms which form on small perforating end arteries deep in the brain. Less common sources of bleeding are arteriovenous malformations (AVMs), tumours, trauma and amyloid. The most common site affected is the internal capsule area which usually results in a complete hemiparesis. When the source of bleeding is in the brain stem, or cerebellum there is usually quadriparesis with cranial nerve palsies, ataxia and coma. Subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) is mainly caused by a ruptured underlying intracranial saccular (berry) aneurysm arising from the circle of Willis and less frequently AVM.

Figure 5.4 Intracerebral haemorrhage (ICH). CT scans showing ICH.

Key points

- stroke is a leading cause of death in adults in Africa

- the main causes are ischaemia & haemorrhage

- ischaemia is caused by atheroma & embolism

- haemorrhagic strokes arise from ICH or SAH

- main causes are hypertension & aneurysms

Pathogenesis

When the blood supply to the brain is lost acutely either as a result of ischaemia or haemorrhage, a core area of the brain will undergo infarction/necrosis. This core area of the brain is irreversibly damaged. However in ischaemia, because of collateral blood supply, a surrounding area called a penumbra remains potentially viable for a limited time. This time period is usually about 3-4.5 hours, during which it will recover if the blood supply is restored. This is the target for the early treatment directed at decreasing thrombosis and improving blood supply. The swelling in the brain is caused by cytotoxic and vasogenic oedema as a result of infarction or haemorrhage. This is frequently responsible for the clinical deterioration in the days immediately following on the acute stroke.

Vascular Risk Factors

The main risk factors for stroke are hypertension, atrial fibrillation, diabetes mellitus, smoking and lack of exercise (Table 5.1). Together, these account for over two thirds of all strokes and represent modifiable risk factors. The risk of stroke increases exponentially with age, with a much greater risk in the elderly population. Hypertension is the most important modifiable risk factor for both ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke. The risk almost doubles with every 7.5 mm Hg rise in diastolic pressure even within the normal range of blood pressure. Established cardiovascular disease is an important risk factor for stroke, particularly a previous stroke or TIA, atrial fibrillation, rheumatic mitral valve disease and heart failure. Diabetes, high cholesterol and low density lipoproteins, sickle cell disease, the oral contraceptive pill, migraine and infections are all known risk factors for ischaemic stroke. The main modifiable life style risk factors include diet, salt intake, obesity, lack of exercise, cigarette smoking and increased alcohol consumption.

Table 5.1 Main risk factors for stroke

| Risk factors | Relative degree of risk |

| ageing | highest |

| hypertension atrial fibrillation previous stroke or TIA | very high |

| ischaemic heart disease diabetes | high |

| life style: diet increased salt intake lack of exercise smoking alcohol | moderate |

| obesity | low |

Key points

- age is the strongest non modifiable risk factor for stroke

- hypertension and AF are among the main modifiable risk factors in secondary prevention

- life style is the major modifiable risk factor in primary prevention

Main causes of stroke

- atheroma

- hypertension

- cardioembolism

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The key features of a stroke are a sudden onset of a focal neurological deficit in a person who was previously well. Strokes occur more frequently at night and in the early morning. The clinical findings will depend on the type of stroke, the vascular site affected and the underlying cause. The most common presentations are a sudden, unilateral loss of power or sensation in an arm or leg or both, a loss of speech, vision or balance (Table 5.2). These help to localize the site of origin of the stroke. There are no features that can reliably distinguish between ischaemia and haemorrhage, although headache, vomiting, complete hemiparesis, reduced level of consciousness and severe hypertension are more common in haemorrhage. In subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH), the onset is characterized by a new, sudden and severe headache with neck stiffness, usually without any focal neurological deficit, but alteration or loss of consciousness may be present. If the patient is unable to give a history, then the details should be obtained from a relative. The general examination should be directed at looking for the main underlying risk factors for stroke, including hypertension, atrial fibrillation, cardiac murmurs, carotid bruits and signs of systemic illness. CT imaging is usually necessary to distinguish between the two main types of stroke.

Table 5.2 Main clinical features of stroke

| sudden onset either all at once or over minutes or hours focal neurological symptoms and signs loss of neurological function motor loss: weakness of one side or part of one side of the body sensory loss: decreased sensation on one side or part of one side of the body aphasia: loss or impairment of speech, understanding, reading or writing visual: loss of vision to one side, hemianopia (patient usually unaware) other symptoms: altered consiousness, dysphagia, dysarthria, ataxia, diplopia, quadriparesis |

Localization

Ischaemic strokes can be divided into anterior and posterior circulation strokes. Anteriorly the internal carotid artery (ICA) divides to form the anterior and middle cerebral arteries (ACA & MCA). Posteriorly the vertebral arteries join at the lower pons to form the basilar artery which in turn divides into two posterior cerebral arteries (PCA). The anterior and posterior circulations are joined in front by the anterior communicating artery and at the back by the posterior communicating artery to form the circle of Willis (Fig. 5.1). This ensures collateral circulation in the brain. The MCA supplies the anterior lateral two thirds of the brain and the ACA supplies the remaining medial two thirds. The PCA supplies the posterior one third or the occipital lobe. The brain stem and cerebellum are supplied in turn by the vertebral and basilar arteries. The most common sites affected are the MCA followed by the ACA, followed by lacunar and PCA (Table 5.3).

Table 5.3 Localization and strokes

| Artery | Main clinical findings |

| Internal carotid artery | hemiplegia, (arm = face = leg) hemisensory deficit hemianopia |

| Anterior cerebral artery | hemiplegia, (leg > arm) |

| Middle cerebral artery | hemiplegia & numbness (face = arm > leg) aphasia *(if the dominant hemisphere involved) hemianopia sensory inattention (if the non dominant hemisphere involved) |

| Posterior cerebral artery | hemianopia |

| Lacunar | hemiplegia, (face = arm = leg) hemisensory, (face = arm = leg) |

| Vertebro-basilar arteries (brain stem) | dysphagia, dysarthria, hemiplegia/quadriplegia cranial nerve palsies ataxia |

* left hemisphere is dominant in most (>90%) right handed persons and in approx 70% of left handed persons

- stroke is a sudden neurological deficit due to a vascular cause

- person is usually aware of a neurological deficit over minutes or less commonly hours

- hemiparesis is the most common finding

- neurological findings help to localize the site of the lesion

- most strokes occur in the anterior circulation

TRANSIENT ISCHAEMIC ATTACK (TIA)

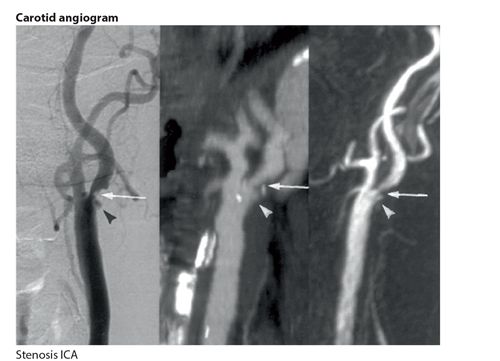

A TIA is a sudden ischaemic focal neurological deficit that completely recovers in less than 24 hours. They typically last for minutes not hours. They are mostly caused by thromboemboli arising from the internal carotid arteries in the neck and their branches. Other sources of emboli are atrial fibrillation and heart disease. The vascular territory involved determines the neurological findings and the presentations are similar to those already outlined for stroke but usually less severe. All TIAs should be investigated in a similar manner and with the same sense of urgency as stroke (Table 5.4). After a TIA the overall risk for stroke is about 10% per year, the greatest risk being in the days and weeks following the TIA. If the TIA lasts >90 mins in a person at risk, then the likelihood of a stroke is greatest (4-8%) within the next 48 hours and the patient requires urgent hospital admission. The aim of investigations and management is to identify and modify preventable risk factors such as smoking, exercise, diet and alcohol and aggressively treat underlying diseases such as carotid artery stenosis (Fig. 5.5), hypertension, diabetes and atrial fibrillation (Table 5.1). Antiplatelet drugs and anticoagulants are used as in the prevention of stroke (Table 5.6).

Table 5.4 Investigations for stroke

| Department | Investigation | Risk factor |

| Haematology | FBC, ESR, sickle cell test | anaemia, polycythaemia, infection, vasculitis, sickle cell disease |

| Biochemistry | blood glucose, creatinine, electrolytes, liver function tests, lipids | diabetes, renal disease, hyperlipidaemia |

| Serology | HIV, VDRL | infections |

| Microbiology | malaria parasites, blood culture (if febrile) | infections |

| Cardiology | ECG | atrial fibrillation, myocardial infarction |

| Imaging | chest X-ray CT/MRI of head | cardiomegaly, hypertension ischaemia or haemorrhage |

| Ultrasound | echo heart (if cardiac origin suspected) carotid doppler (if carotid origin suspected) | mitral valve disease, thrombus, endocarditis large vessel atheroma |

Figure 5.5 Internal carotid artery stenosis

Key points

Differential diagnosis

A history of a sudden onset of focal neurological deficit is almost always diagnostic of stroke. The differential diagnosis includes other disorders presenting with similar acute or semi acute neurological presentations. These include opportunistic processes in HIV disease, subdural haematoma, mass lesions, Todd’s paralysis after an unwitnessed seizure, and other causes of acute encephalopathy. However in these cases the correct diagnosis should be suggested by a different clinical history, sub-acute onset and progressive nature of the neurological deficit. Venous sinus thrombosis may present with a stroke but this is uncommon. The clinical context, usually a pre-menopausal female with typical fundoscopy changes of venous engorgement with haemorrhages should suggest the correct diagnosis. A history of recent head injury or fall suggests the possibility of subdural haematoma (SDH), although a history of trauma may be absent (Chapter 19). CT scan of the brain may be necessary to make the correct diagnosis. There are a number of other medical conditions that can mimic a stroke or TIA at onset; these include focal seizures, migraine, hypoglycaemia, syncope, and hysteria. These are usually self-limiting often with a history of similar previous episodes and have a normal neurological examination.

INVESTIGATIONS AND DIAGNOSIS

Stroke is a clinical diagnosis and investigations are directed at establishing the cause and preventing recurrences. The main investigations for stroke are outlined in Table 5.4. Computerised tomography (CT) of the head is the investigation of choice in stroke. Ideally this should be done within 24-48 hours of onset of the stroke. Its primary role is to rapidly exclude haemorrhage, thereby allowing the administration of an antiplatelet drug, usually aspirin. In addition, it can determine the nature, size and site of stroke and exclude other disorders. In haemorrhagic stroke, CT shows haemorrhage as a white or hyperdense area almost as soon as it occurs. In small bleeds, the white area persists for around 48 hours while larger bleeds may persist for 1-2 weeks. After two weeks a bleed becomes indistinguishable from an infarct on a CT. CT shows ischaemia as an ill defined dark or hypodense area but this can take 24-48 hours to appear on the scan. Not all infarcts show up on a CT because of decreased sensitivity, small size and also poor imaging of the posterior fossa. If the initial CT is normal and a stroke is still suspected then a scan repeated after 3-7 days may show an infarct. If the clinical diagnosis of a stroke is certain, then a repeat scan may be unnecessary. In SAH the CT is highly sensitive during the first few days, after which it becomes negative and the diagnosis is then confirmed by lumbar puncture showing altered blood or xanthochromia. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is more sensitive than CT for detecting early and small vessel strokes.

Key points

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree